Saskatchewan First Nations and Métis Political Activism, 1922-1946

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News Release

NEWS RELEASE Facing a near $1.0 billion budget deficit, Newfoundland and Labrador can learn from successful Saskatchewan reforms June 24, 2021 For immediate release ST. JOHN’S—When considering ways to recover from its current fiscal crisis, including a huge provincial deficit and the highest debt level of any province, the Newfoundland and Labrador government can heed lessons from Saskatchewan, which faced a similar crisis in the 1990s, finds a new study released today by the Fraser Institute, an independent, non-partisan, Canadian public policy think-tank. “The fiscal situation in Newfoundland and Labrador requires spending reductions to reduce the province’s dauting budget deficit,” said Alex Whalen, policy analyst at the Fraser Institute and co-author of Fiscal lessons for Atlantic Canada from Saskatchewan. Newfoundland and Labrador added almost $2 billion in provincial government debt last year, which is already the highest in Canada (on a per-person basis). While COVID added to the challenges, the province’s fiscal issues long-predate the pandemic. The study highlights how Saskatchewan overcame similar issues – including deficit- financed spending, mounting debt and rising interest costs – in a short period of time. Specifically, Saskatchewan cut spending by almost 12 per cent over two years, in part by eliminating inefficient and unaffordable government programs, and balanced the budget in three years. “Saskatchewan faced similar challenges, but through spending and tax reforms, turned around their fiscal ship,” said Steve Lafleur, senior policy analyst at the Fraser Institute and study co-author. (30) MEDIA CONTACT: Alex Whalen, Policy Analyst Fraser Institute Steve Lafleur, Senior Policy Analyst Fraser Institute To arrange media interviews or for more information, please contact: Drue MacPherson, Fraser Institute (604) 688-0221 ext. -

Saskatchewan Bound: Migration to a New Canadian Frontier

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 1992 Saskatchewan Bound: Migration to a New Canadian Frontier Randy William Widds University of Regina Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Widds, Randy William, "Saskatchewan Bound: Migration to a New Canadian Frontier" (1992). Great Plains Quarterly. 649. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/649 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SASKATCHEWAN BOUND MIGRATION TO A NEW CANADIAN FRONTIER RANDY WILLIAM WIDDIS Almost forty years ago, Roland Berthoff used Europeans resident in the United States. Yet the published census to construct a map of En despite these numbers, there has been little de glish Canadian settlement in the United States tailed examination of this and other intracon for the year 1900 (Map 1).1 Migration among tinental movements, as scholars have been this group was generally short distance in na frustrated by their inability to operate beyond ture, yet a closer examination of Berthoff's map the narrowly defined geographical and temporal reveals that considerable numbers of migrants boundaries determined by sources -

Williston Basin Architecture and Hydrocarbon Potential in Eastern Saskatchewan and Western Manitoba

Williston Basin Architecture and Hydrocarbon Potential in Eastern Saskatchewan and Western Manitoba Kim Kreis, Benoit Beauchamp 1, Ruth Bezys 2 Carol Martiniuk 3, and Steve Whittaker Kreis, L.K., Beauchamp, B., Bezys, R., Martiniuk, C., and Whittaker, S. (2004): Williston Basin architecture and hydrocarbon potential in eastern Saskatchewan and western Manitoba; in Summary of Investigations 2004, Volume 1, Saskatchewan Geological Survey, Sask. Industry Resources, Misc. Rep. 2004-4.1, CD-ROM, Paper A-3, 5p. Abstract The stratigraphic framework and hydrocarbon potential of the Williston Basin are currently being investigated in eastern Saskatchewan and western Manitoba. The Williston Basin Architecture and Hydrocarbon Potential Project (Phase 1) is a two-year collaborative program involving: Saskatchewan Industry and Resources; Manitoba Industry, Economic Development and Mines; and Natural Resources Canada. Regional geological, hydrogeological, geophysical, and remotely sensed imagery analyses are being performed on Phanerozoic-aged rocks from the top of the Precambrian basement to uppermost Cretaceous. Consultants and researchers from federal and provincial governments, and universities are involved in this regional study, the results of which are expected to enhance our knowledge of subsurface mineral potential (e.g., of brines and potash) and hydrocarbon- migration paths and entrapment mechanisms within and beyond areas of known production. Keywords: Saskatchewan, Manitoba, Williston Basin, hydrocarbons, oil, Phanerozoic, stratigraphy, geophysics, geochemistry, Digital Elevation Model (DEM), Targeted Geoscience Initiative (TGI). 1. Introduction Steadily increasing demand for hydrocarbons by the North American economy is widening the gap between supply and demand. Geoscience knowledge is an essential component of hydrocarbon- and mineral-exploration strategies. Over the past several decades, however, both industry and governments in Canada have generally reduced funding for geoscience investigations. -

Cluster 2: a Profound Ambivalence: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Relations with Government

A Profound Ambivalence: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Relations with Government by Ted Longbottom C urrent t opiCs in F irst n ations , M étis , and i nuit s tudies Cluster 2: a profound ambivalence: First nations, Métis, and inuit relations with Government Setting the Stage: Economics and Politics by Ted Longbottom L earninG e xperienCe 2.1: s ettinG the s taGe : e ConoMiCs and p oLitiCs enduring understandings q First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples share a traditional worldview of harmony and balance with nature, one another, and oneself. q First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples represent a diversity of cultures, each expressed in a unique way. q Understanding and respect for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples begin with knowledge of their pasts. q Current issues are really unresolved historical issues. q First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples want to be recognized for their contributions to Canadian society and to share in its successes. essential Questions Big Question How would you describe the relationship that existed among Indigenous nations and between Indigenous nations and the European newcomers in the era of the fur trade and the pre-Confederation treaties? Focus Questions 1. How did Indigenous nations interact? 2. How did First Nations’ understandings of treaties differ from that of the Europeans? 3. What were the principles and protocols that characterized trade between Indigenous nations and the traders of the Hudson’s Bay Company? 4. What role did Indigenous nations play in conflicts between Europeans on Turtle Island? Cluster 2: a profound ambivalence 27 Background Before the arrival of the Europeans, First Peoples were self-determining nations. -

Grade 12 Canadian History: a Postcolonial Analysis. A

GRADE 12 CANADIAN HISTORY: A POSTCOLONIAL ANALYSIS. A Thesis Submitted to the College of Graduate Studies and Research in Partial Fulfilment ofthe Requirements for the Degree ofMasters ofEducation in the Department ofEducational Foundations University ofSaskatchewan Saskatoon by T. Scott Farmer Spring 2004 © Copyright T. Scott Farmer, 2004. All Rights reserved. PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a Postgraduate degree from the University of Saskatchewan, I agree that the Libraries of this University may make it freely available for inspection. I further agree that permission for copying ofthis thesis in any manner, in whole or in part, for scholarly purposes may be granted by the professor or professors who supervised my thesis work or, in their absence, by the Head of the Department or the Dean of the College in which my thesis work was done. It is understood that any copying or publication or use of this thesis or parts thereof for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. It is also understood that due recognition shall be given to me and to the University of Saskatchewan in any scholarly use which may be made ofany material in my thesis. Requests for permission to copy or to make other use of material in this thesis in whole or part should be addressed to: Head ofthe Department ofEducational Foundations University ofSaskatchewan Saskatoon, Saskatchewan S7N OXl ABSTRACT The History 30: Canadian Studies Curriculum Guide and the History 30: Canadian Studies A Teacher's Activity Guide provide teachers ofgrade twelve Canadian history direction and instruction. -

Edmund Morris Among the Saskatchewan Indians and the Fort Qu'appelle Monument

EDMUND MORRIS AMONG THE SASKATCHEWAN INDIANS AND THE FORT QU'APPELLE MONUMENT By Jean McGill n 1872 the government of Canada appointed Alexander Morris the first Chief Justice of Manitoba. The same year he succeeded A. G. Archibald as Lieu I tenant-Governor of Manitoba and the North-West Territories. Archibald had already acted as a commissioner of the federal government in negotiating Treaties Nos. 1 and 2 with the Indians of Manitoba. Morris was com missioned in 1873 to carry on negotiations with Indians of the western plains and some Manitoba Indians not present at the first two treaties. By the time Alexander Morris's term of office had expired in 1877 he had negotiated the signing of Treaties No. 3 (North-West Angle), 4 (Fort Qu'Appelle), 5 (Lake Winnipeg), 6 (Forts Carlton and Pitt), and the Revision of Treaties Nos. 1 and 2. Morris later documented the meetings, negotiations, and wording of all of the treaties completed prior to 1900 in a book entitled The Treaties of Canada with the Indians ofManitoba and the North west Territories which was published in 1888. He returned to Toronto with his family and later was persuaded to run for office in the Ontario legislature where he represented Toronto for a number of years. Edmund Morris, youngest of a family of eleven, was born two years before the family went to Manitoba. Indian chiefs and headmen in colourful regalia frequently came to call on the Governor and as a child at Government House in Winnipeg, Edmund was exposed to Indian culture for the Indians invariably brought gifts, often for Mrs. -

An Indian Chief, an English Tourist, a Doctor, a Reverend, and a Member of Ppparliament: the Journeys of Pasqua’S’S’S Pictographs and the Meaning of Treaty Four

The Journeys of Pasqua’s Pictographs 109 AN INDIAN CHIEF, AN ENGLISH TOURIST, A DOCTOR, A REVEREND, AND A MEMBER OF PPPARLIAMENT: THE JOURNEYS OF PASQUA’S’S’S PICTOGRAPHS AND THE MEANING OF TREATY FOUR Bob Beal 7204 76 Street Edmonton, Alberta Canada, T6C 2J5 [email protected] Abstract / Résumé Indian treaties of western Canada are contentious among historians, First Nations, governments, and courts. The contemporary written docu- mentation about them has come from one side of the treaty process. Historians add information from such disciplines as First Nations Tradi- tional Knowledge and Oral History to draw as complete a picture as possible. Now, we have an additional source of written contemporary information, Chief Pasqua’s recently rediscovered pictographs showing the nature of Treaty Four and its initial implementation. Pasqua’s ac- count, as contextualized here, adds significantly to our knowledge of the western numbered treaty process. The pictographs give voice to Chief Pasqua’s knowledge. Les traités conclus avec les Indiens de l’Ouest canadien demeurent liti- gieux pour les historiens, les Premières nations, les gouvernements et les tribunaux. Les documents contemporains qui discutent des traités ne proviennent que d’une seule vision du processus des traités. Les historiens ajoutent des renseignements provenant de disciplines telles que les connaissances traditionnelles et l’histoire orale des Autochto- nes. Ils bénéficient désormais d’une nouvelle source écrite contempo- raine, les pictogrammes récemment redécouverts du chef Pasqua, qui illustrent la nature du Traité n° 4 et les débuts de son application. Le compte rendu du chef, tel que replacé dans son contexte, est un ajout important à notre connaissance du processus des traités numérotés dans l’Ouest canadien. -

Treaties in Canada, Education Guide

TREATIES IN CANADA EDUCATION GUIDE A project of Cover: Map showing treaties in Ontario, c. 1931 (courtesy of Archives of Ontario/I0022329/J.L. Morris Fonds/F 1060-1-0-51, Folder 1, Map 14, 13356 [63/5]). Chiefs of the Six Nations reading Wampum belts, 1871 (courtesy of Library and Archives Canada/Electric Studio/C-085137). “The words ‘as long as the sun shines, as long as the waters flow Message to teachers Activities and discussions related to Indigenous peoples’ Key Terms and Definitions downhill, and as long as the grass grows green’ can be found in many history in Canada may evoke an emotional response from treaties after the 1613 treaty. It set a relationship of equity and peace.” some students. The subject of treaties can bring out strong Aboriginal Title: the inherent right of Indigenous peoples — Oren Lyons, Faithkeeper of the Onondaga Nation’s Turtle Clan opinions and feelings, as it includes two worldviews. It is to land or territory; the Canadian legal system recognizes title as a collective right to the use of and jurisdiction over critical to acknowledge that Indigenous worldviews and a group’s ancestral lands Table of Contents Introduction: understandings of relationships have continually been marginalized. This does not make them less valid, and Assimilation: the process by which a person or persons Introduction: Treaties between Treaties between Canada and Indigenous peoples acquire the social and psychological characteristics of another Canada and Indigenous peoples 2 students need to understand why different peoples in Canada group; to cause a person or group to become part of a Beginning in the early 1600s, the British Crown (later the Government of Canada) entered into might have different outlooks and interpretations of treaties. -

"It Was Only a Treaty"

"IT WAS ONLY A TREATY" TREATY 11 ACCORDING TO THE DENE OF THE MACKENZIE VALLEY Revised for The Dene Nation and The Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples Rene M.J. Lamothe April, 1996 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY "It Was Only A Treaty" provides some basic concepts about Treaty 11 from a Dene perspective. The paper sets out cultural parameters of Dene life by providing information on key social, economic, political and spiritual aspects of Dene life with the intention of providing readers with the historical and legal context in which the Dene live. Through the presentation of the context of Dene life, the paper sets the parameters which limit Dene decision making with regards to the land and relationships with non-Dene. Some of the information may be viewed by academic interests to be outside the scope of what they consider "sound knowledge" about the Dene. The information, however, is provided from within the context of Dene experience, much of which, being of a spiritual nature, is not readily available to the "outside" academic. This information is also intended, in part, to set the stage for the non-Dene to better understand the social, political and economic conditions in play in Dene society in 1921. Understanding the context from which the Dene approached the Crown's Treaty Party is fundamental to understanding the Dene version of Treaty 11. The paper explores government interests in the territory covered by Treaty 11. Although this section is very limited in its' scope and does not provide conclusive evidence about the motives of government, it provides information on land surveys which took place in Dene territory before Treaty was made, as well as bringing to light some of the political and economic pressures which have been at play within the Euro-Canadian/American public since contact. -

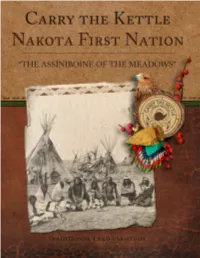

CTK-First-Nations Glimpse

CARRY THE KETTLE NAKOTA FIRST NATION Historical and Current Traditional Land Use Study JIM TANNER, PhD., DAVID R. MILLER, PhD., TRACEY TANNER, M.A., AND PEGGY MARTIN MCGUIRE, PhD. On the cover Front Cover: Fort Walsh-1878: Grizzly Bear, Mosquito, Lean Man, Man Who Took the Coat, Is Not a Young Man, One Who Chops Wood, Little Mountain, and Long Lodge. Carry the Kettle Nakota First Nation Historical and Current Traditional Land Use Study Authors: Jim Tanner, PhD., David R. Miller, PhD., Tracey Tanner, M.A., and Peggy Martin McGuire, PhD. ISBN# 978-0-9696693-9-5 Published by: Nicomacian Press Copyright @ 2017 by Carry the Kettle Nakota First Nation This publication has been produced for informational and educational purposes only. It is part of the consultation and reconciliation process for Aboriginal and Treaty rights in Canada and is not for profit or other commercial purposes. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatever without the written permission of the Carry the Kettle First Nation, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews. Layout and design by Muse Design Inc., Calgary, Alberta. Printing by XL Print and Design, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 Table of Figures 3 Letter From Carry the Kettle First Nation Chief 4 Letter From Carry the Kettle First Nation Councillor Kurt Adams 5 Elder and Land User Interviewees 6 Preface 9 Introduction 11 PART 1: THE HISTORY CHAPTER 1: EARLY LAND USE OF THE NAKOTA PEOPLES 16 Creation Legend 16 Archaeological Evidence 18 Early -

Diabetes Directory

Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory February 2015 A Directory of Diabetes Services and Contacts in Saskatchewan This Directory will help health care providers and the general public find diabetes contacts in each health region as well as in First Nations communities. The information in the Directory will be of value to new or long-term Saskatchewan residents who need to find out about diabetes services and resources, or health care providers looking for contact information for a client or for themselves. If you find information in the directory that needs to be corrected or edited, contact: Primary Health Services Branch Phone: (306) 787-0889 Fax : (306) 787-0890 E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgement The Saskatchewan Ministry of Health acknowledges the efforts/work/contribution of the Saskatoon Health Region staff in compiling the Saskatchewan Diabetes Directory. www.saskatchewan.ca/live/health-and-healthy-living/health-topics-awareness-and- prevention/diseases-and-disorders/diabetes Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................................................... - 1 - SASKATCHEWAN HEALTH REGIONS MAP ............................................. - 3 - WHAT HEALTH REGION IS YOUR COMMUNITY IN? ................................................................................... - 3 - ATHABASCA HEALTH AUTHORITY ....................................................... - 4 - MAP ............................................................................................................................................... -

Indigenous Perspectives Collection Bora Laskin Law Library

fintFenvir Indigenous Perspectives Collection Bora Laskin Law Library 2009-2019 B O R A L A S K I N L A W L IBRARY , U NIVERSITY OF T O R O N T O F A C U L T Y O F L A W 21 things you may not know about the Indian Act / Bob Joseph KE7709.2 .J67 2018. Course Reserves More Information Aboriginal law / Thomas Isaac. KE7709 .I823 2016 More Information The... annotated Indian Act and aboriginal constitutional provisions. KE7704.5 .A66 Most Recent in Course Reserves More Information Aboriginal autonomy and development in northern Quebec and Labrador / Colin H. Scott, [editor]. E78 .C2 A24 2001 More Information Aboriginal business : alliances in a remote Australian town / Kimberly Christen. GN667 .N6 C47 2009 More Information Aboriginal Canada revisited / Kerstin Knopf, editor. E78 .C2 A2422 2008 More Information Aboriginal child welfare, self-government and the rights of indigenous children : protecting the vulnerable under international law / by Sonia Harris-Short. K3248 .C55 H37 2012 More Information Aboriginal conditions : research as a foundation for public policy / edited by Jerry P. White, Paul S. Maxim, and Dan Beavon. E78 .C2 A2425 2003 More Information Aboriginal customary law : a source of common law title to land / Ulla Secher. KU659 .S43 2014 More Information Aboriginal education : current crisis and future alternatives / edited by Jerry P. White ... [et al.]. E96.2 .A24 2009 More Information Aboriginal education : fulfilling the promise / edited by Marlene Brant Castellano, Lynne Davis, and Louise Lahache. E96.2 .A25 2000 More Information Aboriginal health : a constitutional rights analysis / Yvonne Boyer.