Proquest Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Restorative Justice in the Face of Atrocities

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, Volume 496 Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Humanities Education and Social Sciences (ICHESS 2020) Restorative Justice in the Face of Atrocities Yuanmeng Zhang [email protected] Flintridge Preparatory School Abstract The traditional justice serves the justice of the accused, while the restorative justice serves the justice of the victims, which is particularly important to the victims of war and has the function of containing the war. With the development of human society, war is inevitable, but the form will change. Restorative justice will ensure the vulnerable groups and warn the war initiators. Keywords:war,restorative,containing,justice October 1st, 1946. 3 Prior to the trial, the idea of 1. Introduction “retributive justice” was predominating in the law court. This form of justice often takes on an element of After the Second World War, disputes on the treatments of punishment or vengeance, a retribution to what the former Nazi soldiers has heightened debates criminal had done. The term also denotes “harsh internationally. According to many, the crimes of these treatment” because, according to the Stanford soldiers as well as their impacts are incurable; therefore, it Encyclopedia of Philosophy, retributive justice always is justified for Nazis to receive retributive justice- a form comes with “cost or hardship” for the criminal. 4 In of justice “morally impermissible intentionally to punish addition, these hardships are imposed by will upon the the innocent or to inflict disproportionately large guilty rather than accidental. In other words, the adverse punishments on wrongdoers.1” Before, during the Second effects which the use of retributive justice had purposely World War and long after, anti-semetic sentiment towards inflicted can be justified as “punishments” rather than the Jewish community was always high since the Nazi had “harms. -

Saskatchewan Discovery Guide

saskatchewan discovery guide OFFICIAL VACATION AND ACCOMMODATION PLANNER CONTENTS 1 Contents Welcome.........................................................................................................................2 Need More Information? ...........................................................................................4 Saskatchewan Tourism Zones..................................................................................5 How to Use the Guide................................................................................................6 Saskatchewan at a Glance ........................................................................................9 Discover History • Culture • Urban Playgrounds • Nature .............................12 Outdoor Adventure Operators...............................................................................22 Regina..................................................................................................................... 40 Southern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 76 Saskatoon .............................................................................................................. 158 Central Saskatchewan ....................................................................................... 194 Northern Saskatchewan.................................................................................... 276 Events Guide.............................................................................................................333 -

Medicine Wheels

The central rock pile was 14 feet high with several cairns spanned out in different directions, aligning to various stars. Astraeoastronomers have determined that one cairn pointed to Capella, the ideal North sky marker hundreds of years ago. At least two cairns aligned with the solstice sunrise, while the others aligned with the rising points of bright stars that signaled the summer solstice 2000 years ago (Olsen, B, 2008). Astrological alignments of the five satellite cairns around the central mound of Moose Mountain Medicine Wheel from research by John A. Eddy Ph.D. National Geographic January 1977. MEDICINE WHEELS Medicine wheels are sacred sites where stones placed in a circle or set out around a central cairn. Researchers claim they are set up according to the stars and planets, clearly depicting that the Moose Mountain area has been an important spiritual location for millennia. 23 Establishing Cultural Connections to Archeological Artifacts Archeologists have found it difficult to establish links between artifacts and specific cultural groups. It is difficult to associate artifacts found in burial or ancient camp sites with distinct cultural practices because aboriginal livelihood and survival techniques were similar between cultures in similar ecosystem environments. Nevertheless, burial sites throughout Saskatchewan help tell the story of the first peoples and their cultures. Extensive studies of archeological evidence associated with burial sites have resulted in important conclusions with respect to the ethnicity of the people using the southeast Saskatchewan region over the last 1,000 years. In her Master Thesis, Sheila Dawson (1987) concluded that the bison culture frequently using this area was likely the Sioux/ Assiniboine people. -

Edmund Morris Among the Saskatchewan Indians and the Fort Qu'appelle Monument

EDMUND MORRIS AMONG THE SASKATCHEWAN INDIANS AND THE FORT QU'APPELLE MONUMENT By Jean McGill n 1872 the government of Canada appointed Alexander Morris the first Chief Justice of Manitoba. The same year he succeeded A. G. Archibald as Lieu I tenant-Governor of Manitoba and the North-West Territories. Archibald had already acted as a commissioner of the federal government in negotiating Treaties Nos. 1 and 2 with the Indians of Manitoba. Morris was com missioned in 1873 to carry on negotiations with Indians of the western plains and some Manitoba Indians not present at the first two treaties. By the time Alexander Morris's term of office had expired in 1877 he had negotiated the signing of Treaties No. 3 (North-West Angle), 4 (Fort Qu'Appelle), 5 (Lake Winnipeg), 6 (Forts Carlton and Pitt), and the Revision of Treaties Nos. 1 and 2. Morris later documented the meetings, negotiations, and wording of all of the treaties completed prior to 1900 in a book entitled The Treaties of Canada with the Indians ofManitoba and the North west Territories which was published in 1888. He returned to Toronto with his family and later was persuaded to run for office in the Ontario legislature where he represented Toronto for a number of years. Edmund Morris, youngest of a family of eleven, was born two years before the family went to Manitoba. Indian chiefs and headmen in colourful regalia frequently came to call on the Governor and as a child at Government House in Winnipeg, Edmund was exposed to Indian culture for the Indians invariably brought gifts, often for Mrs. -

An Indian Chief, an English Tourist, a Doctor, a Reverend, and a Member of Ppparliament: the Journeys of Pasqua’S’S’S Pictographs and the Meaning of Treaty Four

The Journeys of Pasqua’s Pictographs 109 AN INDIAN CHIEF, AN ENGLISH TOURIST, A DOCTOR, A REVEREND, AND A MEMBER OF PPPARLIAMENT: THE JOURNEYS OF PASQUA’S’S’S PICTOGRAPHS AND THE MEANING OF TREATY FOUR Bob Beal 7204 76 Street Edmonton, Alberta Canada, T6C 2J5 [email protected] Abstract / Résumé Indian treaties of western Canada are contentious among historians, First Nations, governments, and courts. The contemporary written docu- mentation about them has come from one side of the treaty process. Historians add information from such disciplines as First Nations Tradi- tional Knowledge and Oral History to draw as complete a picture as possible. Now, we have an additional source of written contemporary information, Chief Pasqua’s recently rediscovered pictographs showing the nature of Treaty Four and its initial implementation. Pasqua’s ac- count, as contextualized here, adds significantly to our knowledge of the western numbered treaty process. The pictographs give voice to Chief Pasqua’s knowledge. Les traités conclus avec les Indiens de l’Ouest canadien demeurent liti- gieux pour les historiens, les Premières nations, les gouvernements et les tribunaux. Les documents contemporains qui discutent des traités ne proviennent que d’une seule vision du processus des traités. Les historiens ajoutent des renseignements provenant de disciplines telles que les connaissances traditionnelles et l’histoire orale des Autochto- nes. Ils bénéficient désormais d’une nouvelle source écrite contempo- raine, les pictogrammes récemment redécouverts du chef Pasqua, qui illustrent la nature du Traité n° 4 et les débuts de son application. Le compte rendu du chef, tel que replacé dans son contexte, est un ajout important à notre connaissance du processus des traités numérotés dans l’Ouest canadien. -

A Selected Western Canada Historical Resources Bibliography to 1985 •• Pannekoek

A Selected Western Canada Historical Resources Bibliography to 1985 •• Pannekoek Introduction The bibliography was compiled from careful library and institutional searches. Accumulated titles were sent to various federal, provincial and municipal jurisdictions, academic institutions and foundations with a request for correction and additions. These included: Parks Canada in Ottawa, Winnipeg (Prairie Region) and Calgary (Western Region); Manitoba (Depart- ment of Culture, Heritage and Recreation); Saskatchewan (Department of Culture and Recreation); Alberta (Historic Sites Service); and British Columbia (Ministry of Provincial Secretary and Government Services . The municipalities approached were those known to have an interest in heritage: Winnipeg, Brandon, Saskatoon, Regina, Moose Jaw, Edmonton, Calgary, Medicine Hat, Red Deer, Victoria, Vancouver and Nelson. Agencies contacted were Heritage Canada Foundation in Ottawa, Heritage Mainstreet Projects in Nelson and Moose Jaw, and the Old Strathcona Foundation in Edmonton. Various academics at the universities of Calgary and Alberta were also contacted. Historical Report Assessment Research Reports make up the bulk of both published and unpublished materials. Parks Canada has produced the greatest quantity although not always the best quality reports. Most are readily available at libraries and some are available for purchase. The Manuscript Report Series, "a reference collection of .unedited, unpublished research reports produced in printed form in limited numbers" (Parks Canada, 1983 Bibliography, A-l), are not for sale but are deposited in provincial archives. In 1982 the Manuscript Report Series was discontinued and since then unedited, unpublished research reports are produced in the Microfiche Report Series/Rapports sur microfiches. This will now guarantee the unavailability of the material except to the mechanically inclined, those with excellent eyesight, and the extremely diligent. -

Rupturing the Myth of the Peaceful Western Canadian Frontier: a Socio-Historical Study of Colonization, Violence, and the North West Mounted Police, 1873-1905

Rupturing the Myth of the Peaceful Western Canadian Frontier: A Socio-Historical Study of Colonization, Violence, and the North West Mounted Police, 1873-1905 by Fadi Saleem Ennab A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies of The University of Manitoba in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Department of Sociology University of Manitoba Winnipeg Copyright © 2010 by Fadi Saleem Ennab TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... iii CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 1 CHAPTER TWO: LITERATURE REVIEW ..................................................................... 8 Mythologizing the Frontier .......................................................................................... 8 Comparative and Critical Studies on Western Canada .......................................... 15 Studies of Colonial Policing and Violence in Other British Colonies .................... 22 Summary of Literature ............................................................................................... 32 Research Questions ..................................................................................................... 33 CHAPTER THREE: THEORETICAL CONSIDERATIONS ......................................... 35 CHAPTER -

Frontier Re-Imagined: the Mythic West in the Twentieth Century

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2018 Frontier Re-Imagined: The yM thic West In The Twentieth Century Michael Craig Gibbs University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gibbs, M.(2018). Frontier Re-Imagined: The Mythic West In The Twentieth Century. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5009 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FRONTIER RE-IMAGINED : THE MYTHIC WEST IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY by Michael Craig Gibbs Bachelor of Arts University of South Carolina-Aiken, 1998 Master of Arts Winthrop University, 2003 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2018 Accepted by: David Cowart, Major Professor Brian Glavey, Committee Member Tara Powell, Committee Member Bradford Collins, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Michael Craig Gibbs All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION To my mother, Lisa Waller: thank you for believing in me. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the following people. Without their support, I would not have completed this project. Professor Emeritus David Cowart served as my dissertation director for the last four years. He graciously agreed to continue working with me even after his retirement. -

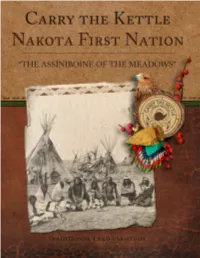

CTK-First-Nations Glimpse

CARRY THE KETTLE NAKOTA FIRST NATION Historical and Current Traditional Land Use Study JIM TANNER, PhD., DAVID R. MILLER, PhD., TRACEY TANNER, M.A., AND PEGGY MARTIN MCGUIRE, PhD. On the cover Front Cover: Fort Walsh-1878: Grizzly Bear, Mosquito, Lean Man, Man Who Took the Coat, Is Not a Young Man, One Who Chops Wood, Little Mountain, and Long Lodge. Carry the Kettle Nakota First Nation Historical and Current Traditional Land Use Study Authors: Jim Tanner, PhD., David R. Miller, PhD., Tracey Tanner, M.A., and Peggy Martin McGuire, PhD. ISBN# 978-0-9696693-9-5 Published by: Nicomacian Press Copyright @ 2017 by Carry the Kettle Nakota First Nation This publication has been produced for informational and educational purposes only. It is part of the consultation and reconciliation process for Aboriginal and Treaty rights in Canada and is not for profit or other commercial purposes. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatever without the written permission of the Carry the Kettle First Nation, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in reviews. Layout and design by Muse Design Inc., Calgary, Alberta. Printing by XL Print and Design, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan. Table of Contents Table of Contents 1 Table of Figures 3 Letter From Carry the Kettle First Nation Chief 4 Letter From Carry the Kettle First Nation Councillor Kurt Adams 5 Elder and Land User Interviewees 6 Preface 9 Introduction 11 PART 1: THE HISTORY CHAPTER 1: EARLY LAND USE OF THE NAKOTA PEOPLES 16 Creation Legend 16 Archaeological Evidence 18 Early -

Story Idea Als

Story Idea Krefeld, im Januar 2019 Historischer Familienspaß Geschichte zum Anfassen an Saskatchewans National Historic Sites Obwohl die Siedlungsgeschichte Kanadas für europäische Verhältnisse vergleichsweise jung ist, hat das Ahorn-Land viel Spannendes aus der Vergangenheit zu berichten! Verschiedene ausgewählte Bauwerke oder Naturdenkmäler, an denen sich einst signifikante Ereignisse zugetragen haben, zählen zu den kanadischen „National Historic Sites“. Sie illustrieren einige der entscheidendsten Momente in der Geschichte Kanadas. In den Sommermonaten lassen Mitarbeiter in zeitgenössischer Kleidung hier die Vergangenheit wieder aufleben. Mit bewegender Geschichte und spannenden Geschichten nehmen sie die Besucher auf eine interaktive Zeitreise mit. Auch in der Prärieprovinz Saskatchewan befinden sich einige dieser historischen Stätten, die Familienspaß für Jung und Alt versprechen. An der Batoche National Historic Site steht eine Zeitreise ins 19. Jahrhundert auf dem Programm. Am Ufer des South Saskatchewan River zwischen Saskatoon und Prince Albert gelegen, war Batoche nach seiner Gründung im Jahr 1872 eine der größten Siedlungen der Métis, d.h. der Nachfahren europäischer Pelzhändler und Frauen indigener Abstammung. Als sich die Métis gemeinsam mit lokalen Sippen vom Stamm der Cree und Assinoboine im Rahmen der Nordwest Rebellion gegen die kanadische Regierung auflehnten, war die Stadt im Jahr 1885 Schauplatz der entscheidenden Schlacht von Batoche. Noch heute sind an der Batoche National Historic Site die Einschlusslöcher der letzten Kämpfe zu sehen. Als Besucher kann man sich lebhaft vorstellen, wie sich die Widersacher seinerzeit auf beiden Seiten des Flusses in Vorbereitung auf den Kampf versammelten. Im Sommer locken hier verschiedene Events, wie beispielsweise das „Back To Batoche Festival“, das seit mehr als 50 Jahren jedes Jahr im Juli stattfindet und die Kultur und Musik der Métis zelebriert. -

“Messengers of Justice and of Wrath”: the Captivity

―Messengers of Justice and of Wrath‖: The Captivity-Revenge Cycle in the American Frontier Romance A dissertation presented to the faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of Ohio University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy Brian P. Elliott June 2011 © 2011 Brian P. Elliott. All Rights Reserved. 2 This dissertation titled ―Messengers of Justice and of Wrath‖: The Captivity-Revenge Cycle in the American Frontier Romance by BRIAN P. ELLIOTT has been approved for the Department of English and the College of Arts and Sciences by Paul C. Jones Associate Professor of English Benjamin M. Ogles Dean, College of Arts and Sciences 3 ABSTRACT ELLIOTT, BRIAN P., Ph.D., June 2011, English ―Messengers of Justice and of Wrath‖: The Captivity-Revenge Cycle in the American Frontier Romance Director of Dissertation: Paul C. Jones This project explores the central importance of captivity and revenge to four novels in the genre of frontier romance: Charles Brockden Brown‘s Edgar Huntly (1799), James Fenimore Cooper‘s Last of the Mohicans (1826), Catharine Maria Sedgwick‘s Hope Leslie (1827), and Robert Montgomery Bird‘s Nick of the Woods (1837). Although a fundamental plot aspect of nearly every work in the genre, the threat of captivity and the necessity of revenge are rarely approached as topics of inquiry, despite their deep connection to the structure and action of the texts. Perhaps most importantly, as critics Jeremy Engels and Greg Goodale note, these twin tropes serve as a way of unifying disparate social groups and creating order; in essence, such depictions function as a form of what Michel Foucault terms ―governmentality,‖ logics of control that originate from non-governmental sources but promote systems of governance. -

Chief Payipwat Biography

Payipwat (1816-1908) Payipwat signed Treaty Number Four in 1875. He argued for land that was promised to him, and it is said that many of his requests were written into Treaty Number Six in 1876. Payipwat, given the name of Kisikawasan at birth, was a Plains Cree born around the southwestern Manitoba or eastern Saskatchewan area in about 1816. As a boy, he and his grandmother were taken prisoner by the Sioux. He grew into manhood with the Sioux people and learned their medicine until he was rescued by the Cree in the 1830s and returned to his people. Upon his return, he was given the name “Payipwat”, often referred to as Piapot or “Hole in the Sioux”. His name translated as “One Who Knows the Secrets of the Sioux”. Payipwat became a highly respected leader among his people and surrounding bands, and in 1875, he signed Treaty Number Four. The treaty was to be a preliminary negotiation, as Payipwat insisted that the treaty must contain a number of additional provisions, but the provisions were never written in. While on the allotted reserve in 1883, there was a disappearance of the bison. That year became a year of sickness and starvation among the people, and this convinced Payipwat to argue for the establishment of a large Indian territory among Cypress Hills. During this time, the federal government began to withhold rations, forcing the Plains Cree to forfeit their resistance and settle into their small reserves. Though the large piece of land was never received, Payipwat managed to negotiate a better location in the Qu’Appelle Valley in 1884.