Eтнолошко-Антропoлошке Свеске 19, (Н.С.) 8 (2012)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Short Course in International Folk Dance, Harry Khamis, 1994

Table of Contents Preface .......................................... i Recommended Reading/Music ........................iii Terminology and Abbreviations .................... iv Basic Ethnic Dance Steps ......................... v Dances Page At Va'ani ........................................ 1 Ba'pardess Leyad Hoshoket ........................ 1 Biserka .......................................... 2 Black Earth Circle ............................... 2 Christchurch Bells ............................... 3 Cocek ............................................ 3 For a Birthday ................................... 3 Hora (Romanian) .................................. 4 Hora ca la Caval ................................. 4 Hora de la Botosani .............................. 4 Hora de la Munte ................................. 5 Hora Dreapta ..................................... 6 Hora Fetalor ..................................... 6 Horehronsky Czardas .............................. 6 Horovod .......................................... 7 Ivanica .......................................... 8 Konyali .......................................... 8 Lesnoto Medley ................................... 8 Mari Mariiko ..................................... 9 Miserlou ......................................... 9 Pata Pata ........................................ 9 Pinosavka ........................................ 10 Setnja ........................................... 10 Sev Acherov Aghcheek ............................. 10 Sitno Zensko Horo ............................... -

Biological Warfare Plan in the 17Th Century—The Siege of Candia, 1648–1669 Eleni Thalassinou, Costas Tsiamis, Effie Poulakou-Rebelakou, Angelos Hatzakis

HISTORICAL REVIEW Biological Warfare Plan in the 17th Century—the Siege of Candia, 1648–1669 Eleni Thalassinou, Costas Tsiamis, Effie Poulakou-Rebelakou, Angelos Hatzakis A little-known effort to conduct biological warfare oc- to have hurled corpses of plague victims into the besieged curred during the 17th century. The incident transpired city (9). During World War II, Japan conducted biological during the Venetian–Ottoman War, when the city of Can- weapons research at facilities in China. Prisoners of war dia (now Heraklion, Greece) was under siege by the Otto- were infected with several pathogens, including Y. pestis; mans (1648–1669). The data we describe, obtained from >10,000 died as a result of experimental infection or execu- the Archives of the Venetian State, are related to an op- tion after experimentation. At least 11 Chinese cities were eration organized by the Venetian Intelligence Services, which aimed at lifting the siege by infecting the Ottoman attacked with biological agents sprayed from aircraft or in- soldiers with plague by attacking them with a liquid made troduced into water supplies or food products. Y. pestis–in- from the spleens and buboes of plague victims. Although fected fleas were released from aircraft over Chinese cities the plan was perfectly organized, and the deadly mixture to initiate plague epidemics (10). We describe a plan—ul- was ready to use, the attack was ultimately never carried timately abandoned—to use plague as a biological weapon out. The conception and the detailed cynical planning of during the Venetian–Ottoman War in the 17th century. the attack on Candia illustrate a dangerous way of think- ing about the use of biological weapons and the absence Archival Sources of reservations when potential users, within their religious Our research has been based on material from the Ar- framework, cast their enemies as undeserving of humani- chives of the Venetian State (11). -

Crete 8 Days

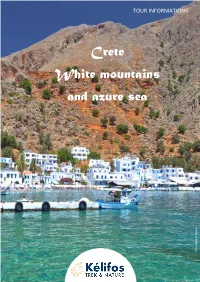

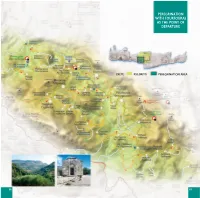

TOUR INFORMATIONS Crete White mountains and azure sea The village of Loutro village The SUMMARY Greece • Crete Self guided hike 8 days 7 nights Itinerant trip Nothing to carry 2 / 5 CYCLP0001 HIGHLIGHTS Chania: the most beautiful city in Crete The Samaria and Agia Irini gorges A good mix of walking, swimming, relaxation and visits of sites www.kelifos.travel +30 698 691 54 80 • [email protected] • CYCGP0018 1 / 13 MAP www.kelifos.travel +30 698 691 54 80 • [email protected] • CYCGP0018 2 / 13 P R O P O S E D ITINERARY Wild, untamed ... and yet so welcoming. Crete is an island of character, a rebellious island, sometimes, but one that opens its doors wide before you even knock. Crete is like its mountains, crisscrossed by spectacular gorges tumbling down into the sea of Libya, to the tiny seaside resorts where you will relax like in a dream. Crete is the quintessence of the alliance between sea and mountains, many of which exceed 2000 meters, especially in the mountain range of Lefka Ori, (means White mountains in Greek - a hint to the limestone that constitutes them) where our hike takes place. Our eight-day tour follows a part of the European E4 trail along the south-west coast of the island with magnificent forays into the gorges of Agia Irini and Samaria for the island's most famous hike. But a nature trip in Crete cannot be confined to a simple landscape discovery even gorgeous. It is in fact associate with exceptional cultural discoveries. The beautiful heritage of Chania borrows from the Venetian and Ottoman occupants who followed on the island. -

A Venetian Rural Villa in the Island of Crete. Traditional and Digital Strategies for a Heritage at Risk Emma Maglio

A Venetian rural villa in the island of Crete. Traditional and digital strategies for a heritage at risk Emma Maglio To cite this version: Emma Maglio. A Venetian rural villa in the island of Crete. Traditional and digital strategies for a heritage at risk. Digital Heritage 2013, Oct 2013, Marseille, France. pp.83-86. halshs-00979215 HAL Id: halshs-00979215 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00979215 Submitted on 15 Apr 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A Venetian rural villa in the island of Crete. Traditional and digital strategies for a heritage at risk Emma Maglio Aix-Marseille University LA3M (UMR 7298-CNRS), LabexMed Aix-en-Provence, France [email protected] Abstract — The Trevisan villa, an example of rural built rather they were regarded with indifference or even hostility»3. heritage in Crete dating back to the Venetian period, was the These ones were abandoned or demolished and only recently, object of an architectural and archaeological survey in order to especially before Greece entered the EU, remains of Venetian study its typology and plan transformations. Considering its heritage were recognized in their value: but academic research ruined conditions and the difficulties in ensuring its protection, a and conservation practices slowly develop. -

SYRTAKI Greek PRONUNCIATION

SYRTAKI Greek PRONUNCIATION: seer-TAH-kee TRANSLATION: Little dragging dance SOURCE: Dick Oakes learned this dance in the Greek community of Los Angeles. Athan Karras, a prominent Greek dance researcher, also has taught Syrtaki to folk dancers in the United States, as have many other teachers of Greek dance. BACKGROUND: The Syrtaki, or Sirtaki, was the name given to the combination of various Hasapika (or Hassapika) dances, both in style and the variation of tempo, after its popularization in the motion picture Alexis Zorbas (titled Zorba the Greek in America). The Syrtaki is danced mainly in the taverns of Greece with dances such as the Zeybekiko (Zeimbekiko), the Tsiftetelli, and the Karsilamas. It is a combination of either a slow hasapiko and fast hasapiko, or a slow hasapiko, hasaposerviko, and fast hasapiko. It is typical for the musicians to "wake things up" after a slow or heavy (vari or argo) hasapiko with a medium and / or fast Hasapiko. The name "Syrtaki" is a misnomer in that it is derived from the most common Greek dance "Syrtos" and this name is a recent invention. These "butcher dances" spread throughout the Balkans and the Near East and all across the Aegean islands, and entertained a great popularity. The origins of the dance are traced to Byzantium, but the Argo Hasapiko is an evolved idiom by Aegean fisherman and their languid lifestyle. The name "Syrtaki" is now embedded as a dance form (meaning "little Syrtos," though it is totally unlike any Syrto dance), but its international fame has made it a hallmark of Greek dancing. -

Memorial Services

BATTLE OF CRETE COMMEMORATIONS ATHENS & CRETE, 12-21 MAY 2019 MEMORIAL SERVICES Sunday, 12 May 2019 10.45 – Commemorative service at the Athens Metropolitan Cathedral and wreath-laying at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Syntagma Square Location: Mitropoleos Street - Syntagama Square, Athens Wednesday, 15 May 2019 08.00 – Flag hoisting at the Unknown Soldier Memorial by the 547 AM/TP Regiment Location: Square of the Unknown Soldier (Platia Agnostou Stratioti), Rethymno town Friday, 17 May 2019 11.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Army Cadets Memorial Location: Kolymbari, Region of Chania 11.30 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the 110 Martyrs Memorial Location: Missiria, Region of Rethymno Saturday, 18 May 2019 10.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Memorial to the Fallen Greeks Location: Latzimas, Rethymno Region 11.30 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Australian-Greek Memorial Location: Stavromenos, Region of Rethymno 13.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Greek-Australian Memorial | Presentation of RSL National awards to Cretan students Location: 38, Igoumenou Gavriil Str. (Efedron Axiomatikon Square), Rethymno town 18.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Memorial to the Fallen Inhabitants Location: 1, Kanari Coast, Nea Chora harbour, Chania town 1 18.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Memorial to the Fallen & the Bust of Colonel Stylianos Manioudakis Location: Armeni, Region of Rethymno 19.30 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Peace Memorial for Greeks and Allies Location: Preveli, Region of Rethymno Sunday, 19 May 2019 10.00 – Official doxology Location: Presentation of Mary Metropolitan Church, Rethymno town 11.00 – Memorial service and wreath-laying at the Rethymno Gerndarmerie School Location: 29, N. -

Registration Certificate

1 The following information has been supplied by the Greek Aliens Bureau: It is obligatory for all EU nationals to apply for a “Registration Certificate” (Veveosi Engrafis - Βεβαίωση Εγγραφής) after they have spent 3 months in Greece (Directive 2004/38/EC).This requirement also applies to UK nationals during the transition period. This certificate is open- dated. You only need to renew it if your circumstances change e.g. if you had registered as unemployed and you have now found employment. Below we outline some of the required documents for the most common cases. Please refer to the local Police Authorities for information on the regulations for freelancers, domestic employment and students. You should submit your application and required documents at your local Aliens Police (Tmima Allodapon – Τμήμα Αλλοδαπών, for addresses, contact telephone and opening hours see end); if you live outside Athens go to the local police station closest to your residence. In all cases, original documents and photocopies are required. You should approach the Greek Authorities for detailed information on the documents required or further clarification. Please note that some authorities work by appointment and will request that you book an appointment in advance. Required documents in the case of a working person: 1. Valid passport. 2. Two (2) photos. 3. Applicant’s proof of address [a document containing both the applicant’s name and address e.g. photocopy of the house lease, public utility bill (DEH, OTE, EYDAP) or statement from Tax Office (Tax Return)]. If unavailable please see the requirements for hospitality. 4. Photocopy of employment contract. -

Greece • Crete • Turkey May 28 - June 22, 2021

GREECE • CRETE • TURKEY MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 Tour Hosts: Dr. Scott Moore Dr. Jason Whitlark organized by GREECE - CRETE - TURKEY / May 28 - June 22, 2021 May 31 Mon ATHENS - CORINTH CANAL - CORINTH – ACROCORINTH - NAFPLION At 8:30a.m. depart from Athens and drive along the coastal highway of Saronic Gulf. Arrive at the Corinth Canal for a brief stop and then continue on to the Acropolis of Corinth. Acro-corinth is the citadel of Corinth. It is situated to the southwest of the ancient city and rises to an elevation of 1883 ft. [574 m.]. Today it is surrounded by walls that are about 1.85 mi. [3 km.] long. The foundations of the fortifications are ancient—going back to the Hellenistic Period. The current walls were built and rebuilt by the Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Ottoman Turks. Climb up and visit the fortress. Then proceed to the Ancient city of Corinth. It was to this megalopolis where the apostle Paul came and worked, established a thriving church, subsequently sending two of his epistles now part of the New Testament. Here, we see all of the sites associated with his ministry: the Agora, the Temple of Apollo, the Roman Odeon, the Bema and Gallio’s Seat. The small local archaeological museum here is an absolute must! In Romans 16:23 Paul mentions his friend Erastus and • • we will see an inscription to him at the site. In the afternoon we will drive to GREECE CRETE TURKEY Nafplion for check-in at hotel followed by dinner and overnight. (B,D) MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 June 1 Tue EPIDAURAUS - MYCENAE - NAFPLION Morning visit to Mycenae where we see the remains of the prehistoric citadel Parthenon, fortified with the Cyclopean Walls, the Lionesses’ Gate, the remains of the Athens Mycenaean Palace and the Tomb of King Agamemnon in which we will actually enter. -

Peregrination with Fourfouras As the Point of Departure

PEREGRINATION WITH FOURFOURAS AS THE POINT OF DEPARTURE CRETE PSILORITIS PEREGRINATION AREA 68 69 FOURFOURAS On the southwest side of Psiloritis, in the prefecture of Rethymno, spreads the area of Amari, which comprises of two municipalities: the municipality of Sivri- tos with Agia Fotini as its capital and the municipality of Kourites with Four- fouras as its capital. Amari is the main area of Psiloritis foot and loom as the most unadulterated and pure area in Crete. Small and big villages show up in the landscape of Amari, a landscape full of contrasts. On one side there is Psiloritis with its steep peaks and age-old oak forests. On the other side, there are two more mountains, Kedros and Samitos, demarcating a rich grain-sown valley which gives life to the whole area. Villages are either climbing on gorges Fourfouras - Kouroutes or spread on plains and make a difference in this verdurous landscape. Nithavri - Apodoulou - Platanos - Lochria Important Minoan dorps and findings are scattered everywhere and reveal From Fourfouras we head south and come across the stockbreeding village of the history of the area. All around the mountaintops, glens and footpaths, Kouroutes, which probably owes its name to the mythical Kourites. Here, there are stone-built country churches which show the byzantine glory of there is a shelter belonging to the Mountaineering Association of Rethymno Amari. Local people are friendly and hospitable in this region. Fourfouras, and this is the smoothest road to Psiloritis peak. Going on in the main road, the capital of the municipality of Kourites is 43 km away from Rethymno. -

Pocono Fall Folk Dance Weekend 2017

Pocono Fall Folk Dance Weekend 2017 Dances, in order of teaching Steve’s and Yves’ notes are included in this document. Steve and Susan 1. Valle e Dados – Kor çë, Albania 2. Doktore – Moh ács/Moha č, Hungary 3. Doktore – Sna šo – Moh ács/Moha č, Hungary 4. Kukunje šće – Tököl (R ác – Serbs), HungaryKezes/Horoa - moldaviai Cs áng ó 5. Kezes/Hora – Moldvai Cs áng ó 6. Bácsol K ék Hora – Circle and Couple ____ 7. Pogonisht ë – Albania 8. Gajda ško 9. Staro Roko Kolo 10. Kupondjijsko Horo 11. Gergelem (Doromb) 12. Gergely T ánc 13. Hopa Hopa Yves and France 1. Srebranski Danets (Bulgaria/Dobrudzha) 2. Svornato (Bulgaria/Rhodopes) 3. Tsonkovo (Bulgaria/Trakia) 4. Nevesto Tsarven Trendafil (Macedonia) 5. Zhensko Graovsko (Bulgaria/Shope) _____ 6. Belchova Tropanka (Bulgaria/Dobrudzha) 7. Draganinata (Bulgaria/ W. Trakia) 8. Chestata (North Bulgaria) 9. Svrlji ški Čačak (East Serbia) DOKTORE I SNAŠO (Mo hács, Hungary) Doktore and Snašo are part of the “South Slavic” ( Délszláv) dance repertoire from Mohács/Moha č, Hungary. Doktore is named after a song text and is originally a Serbian Dance, but is enjoyed by the Croatian Šokci as well. Snašno (young married woman) or Tanac is a Šokac dance. Recording: Workshop CD Formation: Open circle with “V” hold, or M join hands behind W’s back and W’s hands Are on M’s nearest shoulders. Music: 2/4 Meas: DOKTORE 1 Facing center, Step Rft diag fwd to R bending R knee slightly (ct 1); close Lft to Rft and bounce on both feet (ct 2); bounce again on both feet (ct &); 2 Step Lft back to place (bend knee slightly)(ct -

Music and Traditions of Thrace (Greece): a Trans-Cultural Teaching Tool 1

MUSIC AND TRADITIONS OF THRACE (GREECE): A TRANS-CULTURAL TEACHING TOOL 1 Kalliopi Stiga 2 Evangelia Kopsalidou 3 Abstract: The geopolitical location as well as the historical itinerary of Greece into time turned the country into a meeting place of the European, the Northern African and the Middle-Eastern cultures. Fables, beliefs and religious ceremonies, linguistic elements, traditional dances and music of different regions of Hellenic space testify this cultural convergence. One of these regions is Thrace. The aim of this paper is firstly, to deal with the music and the dances of Thrace and to highlight through them both the Balkan and the middle-eastern influence. Secondly, through a listing of music lessons that we have realized over the last years, in schools and universities of modern Thrace, we are going to prove if music is or not a useful communication tool – an international language – for pupils and students in Thrace. Finally, we will study the influence of these different “traditions” on pupils and students’ behavior. Key words: Thrace; music; dances; multi-cultural influence; national identity; trans-cultural teaching Resumo: A localização geopolítica, bem como o itinerário histórico da Grécia através do tempo, transformou o país num lugar de encontro das culturas europeias, norte-africanas e do Médio Oriente. Fábulas, crenças e cerimónias religiosas, elementos linguísticos, danças tradicionais e a música das diferentes regiões do espaço helénico são testemunho desta convergência cultural. Uma destas regiões é a Trácia. O objectivo deste artigo é, em primeiro lugar, tratar da música e das danças da Trácia e destacar através delas as influências tanto dos Balcãs como do Médio Oriente. -

FLOWAID-Crete-Workshop Ierapetra-Nov-2008-Small

FLOW-AID Workshop Proceedings Ierapetra (Crete) (7 th Nov, 2008) 1/33 SIXTH FRAMEWORK PROGRAMME FP6-2005-Global-4, Priority II.3.5 Water in Agriculture: New systems and technologies for irrigation and drainage Farm Level Optimal Water management: Assistant for Irrigation under Deficit Contract no.: 036958 Proceedings of the FLOW-AID workshop in Ierapetra (Crete, Greece) Date: November 7 th , 2008 Project coordinator name: J. Balendonck Project coordinator organisation name: Wageningen University and Research Center Plant Research International Contributions from: Jos Balendonck, PRI – Wageningen (NL) (editor) Nick Sigrimis, Prof Mechanics and Automation – AUA (co-editor, organizer) Frank Kempkes, PRI-Wageningen (NL) Richard Whalley, RRES (UK) Yuksel Tuzel, Ege University – Izmir (Turkey) Luca Incrocci, University of Pisa (Italy) Revision: final Dissemination level: PUBLIC Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Sixth Framework Programme (2002-2006) FLOW-AID Workshop Proceedings Ierapetra (Crete) (7 th Nov, 2008) 2/33 Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................... 2 FLOW-AID WORKSHOP ........................................................................................................... 3 Technical Tour & Ierapetra Conference ..................................................................................... 4 Farm Level Optimal Water management: Assistant for Irrigation under Deficit (FLOW-AID) ...... 7 OBJECTIVES........................................................................................................................