Forced Population Shifts in Crete Under Venetian Rule (13Th-17Th C.): a Practice of Imposing Authority

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

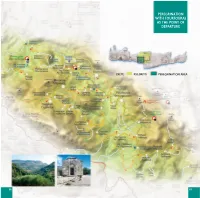

Peregrination with Fourfouras As the Point of Departure

PEREGRINATION WITH FOURFOURAS AS THE POINT OF DEPARTURE CRETE PSILORITIS PEREGRINATION AREA 68 69 FOURFOURAS On the southwest side of Psiloritis, in the prefecture of Rethymno, spreads the area of Amari, which comprises of two municipalities: the municipality of Sivri- tos with Agia Fotini as its capital and the municipality of Kourites with Four- fouras as its capital. Amari is the main area of Psiloritis foot and loom as the most unadulterated and pure area in Crete. Small and big villages show up in the landscape of Amari, a landscape full of contrasts. On one side there is Psiloritis with its steep peaks and age-old oak forests. On the other side, there are two more mountains, Kedros and Samitos, demarcating a rich grain-sown valley which gives life to the whole area. Villages are either climbing on gorges Fourfouras - Kouroutes or spread on plains and make a difference in this verdurous landscape. Nithavri - Apodoulou - Platanos - Lochria Important Minoan dorps and findings are scattered everywhere and reveal From Fourfouras we head south and come across the stockbreeding village of the history of the area. All around the mountaintops, glens and footpaths, Kouroutes, which probably owes its name to the mythical Kourites. Here, there are stone-built country churches which show the byzantine glory of there is a shelter belonging to the Mountaineering Association of Rethymno Amari. Local people are friendly and hospitable in this region. Fourfouras, and this is the smoothest road to Psiloritis peak. Going on in the main road, the capital of the municipality of Kourites is 43 km away from Rethymno. -

Crete (Chapter)

Greek Islands Crete (Chapter) Edition 7th Edition, March 2012 Pages 56 Page Range 256-311 PDF Coverage includes: Central Crete, Iraklio, Cretaquarium, Knossos, Arhanes, Zaros, Matala, Rethymno, Moni Arkadiou, Anogia, Mt Psiloritis, Spili, Plakias & around, Beaches Between Plakias & Agia Galini, Agia Galini, Western Crete, Hania & around, Samaria Gorge, Hora Sfakion & around, Frangokastello, Anopoli & Inner Sfakia, Sougia, Paleohora, Elafonisi, Gavdos Island, Kissamos-Kastelli & around, Eastern Crete, Lasithi Plateau, Agios Nikolaos & around, Mohlos, Sitia & around, Kato Zakros & Ancient Zakros, and Ierapetra & around. Useful Links: Having trouble viewing your file? Head to Lonely Planet Troubleshooting. Need more assistance? Head to the Help and Support page. Want to find more chapters? Head back to the Lonely Planet Shop. Want to hear fellow travellers’ tips and experiences? Lonely Planet’s Thorntree Community is waiting for you! © Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd. To make it easier for you to use, access to this chapter is not digitally restricted. In return, we think it’s fair to ask you to use it for personal, non-commercial purposes only. In other words, please don’t upload this chapter to a peer-to-peer site, mass email it to everyone you know, or resell it. See the terms and conditions on our site for a longer way of saying the above - ‘Do the right thing with our content. ©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Crete Why Go? Iraklio ............................ 261 Crete (Κρήτη) is in many respects the culmination of the Knossos ........................268 Greek experience. Nature here has been as prolifi c as Picas- Rethymno ..................... 274 so in his prime, creating a dramatic quilt of big-shouldered Anogia ......................... -

The Region of Rethymno

EU Community Initiative Programme Intereeg III B ARCHIMED DI.MA “Discovering Magna Grecia” The Greek-Byzantine Mediterranean itineraries – The Region of Rethymno General Information The town of Rethymnon, capital of the homonym prefecture, is located between the towns of Chania and Herakleion. It lies along the north coast, having to the east one of the largest sand beaches of Crete (length: 12 km) and to the west a rocky coastline that ends up to another large sand beach. To the North is the Cretan and to the South the Libyan Sea. In the east rises the mount of Psiloritis (Ida) and in the south - west the mountain range of Kedros. Between the two massifs is the valley of Amari. On the north - easterly border of the prefecture rises the mount of Kouloukonas (Talaia Mountain). South of the town is the mount of Vrisinas and in a south westerly direction lies the mount of Kryoneritis. Access Airports: Rethymnon is served by the airports of Chania and Heraklion. Port: There is direct connection all year round from the port of Rethymnon to Piraeus. Buses: Public buses can be used daily for travelling to Chania, Heraklion, Siteia and to the most of the townships and villages of the prefecture of Rethymnon. Highways: The main transport routes in the province are a) the new national highway which runs parallel with the north coast, b) the old national highway, which is situated slightly south of the new road, and c) Rethymnon - Spili - Agia Galini - Sfakia road which runs north –south. Natural Geography Rethymnon stretches from the White Mountains until Mount Psiloritis, bordered by the provinces of Hania and Iraklion. -

The Magazine Επίσημη Έκδοση Συλλόγου Ξενοδόχων Νομού Ρεθύμνης / Rethymnon Hotel Owners’ Association Your FREE Copy

Rethymnon spring 2009 the magazine Επίσημη Έκδοση Συλλόγου Ξενοδόχων Νομού Ρεθύμνης / Rethymnon Hotel Owners’ Association Your FREE copy Tα καλύτερα σημεία της πόλης του Ρεθύμνου / The hotspots of the city of Rethymno Αμάρι: ένας παράδεισος στις παρυφές τουτου ΨηλορείτηΨηλορείτη / Amari: a paradise on the foothills of Psiloritis Μια διαδρομή στους μύθους: Σφακάκι-Παγκαλοχώρι-Λούτρα- Μέση- Άγιος Δημήτριος-Πηγή-Άδελε / The route into the myths: Sfakaki-Pagalohori-Loutra- Mesi-Agios Dimitrios-Pigi-Adele Ζωή… ποδήλατο! / Life ….is but a bicycle Χάρτης της πόλης και Γιορτή κρητικού κρασιού και τοπικών του νομού Ρεθύμνης / παραδοσιακών προϊόντων / City map and map of the Wine festival and local Prefecture of Rethymno traditional products the magazine PB the magazine 1 out & more μνήμη σας όταν θα πάρετε τον δρόμο της The hotspots of the city of Rethymno / επιστροφής. Όταν αρχίσει να σουρουπώ- νει, ξεκινάει το σεργιάνι στην πόλη. Μια Τα καλύτερα σηµεία της πόλης του Ρεθύµνου ζωντανή πόλη που όσο περνάει η ώρα γεμίζει κόσμο και σας περιμένει να την By Dimitra Mavridou / Της ∆ήµητρας Μαυρίδου γνωρίσετε. Σας προτείνουμε να δοκιμάσε- τε παγωτό σε κάποιο από τα ζαχαροπλα- στεία πίσω από τη Μαρίνα, για να πάρετε δύναμη και να συνεχίσετε την πεζοπορία. The square dedicated to the unknown soldier First you can see the recently restored square dedicated to the unknown soldier. Στην πλατεία του The Marina / Στη Μαρίνα ........................................................................ 08 Άγνωστου Στρατιώτη The square dedicated to the unknown soldier / Στην ανακαινισμένη πλατεία του Άγνω- Στην πλατεία του Άγνωστου Στρατιώτη .................................................. 09 στου Στρατιώτη θα δείτε από κοντά το ομώνυμο άγαλμα, το οποίο πρόσφατα The promenade / Στην παραλία ........................................................... -

MEDIEVAL FAMAGUSTA: SOCIO-ECONOMIC and SOCIO- CULTURAL DYNAMICS (13Th to 15Th Centuries)

MEDIEVAL FAMAGUSTA: SOCIO-ECONOMIC AND SOCIO- CULTURAL DYNAMICS (13th to 15th Centuries) by SEYIT ÖZKUTLU A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Centre for Byzantine, Ottoman and Modern Greek Studies Institute of Archaeology and Antiquity College of Arts and Law The University of Birmingham October 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT This dissertation examines the socio-economic and socio-cultural dynamics of medieval Famagusta from the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries. Contrary to the traditional historiography suggesting that Famagusta enjoyed commercial privilege after the fall of Acre in 1291 and lost its importance with the Genoese occupation of the city in 1374, this work offers more detailed analysis of economic and social dynamics of the late medieval Famagusta by examining wide-range of archival evidence and argues that Famagusta maintained its commercial importance until the late fifteenth century. In late medieval ages, Famagusta enjoyed economic prosperity due to its crucial role in Levant trade as a supplier and distributor of agricultural and luxury merchandise. -

December 2014 Contents

CyprusTODAY Volume LII, No 4, October - December 2014 Contents Editorial ..........................................................................................2 Axiothea Festival ...........................................................................3 KYPRIA .......................................................................................18 Goddess Aphrodite ......................................................................24 Stelios Votsis ................................................................................28 Perfume of Cyprus ......................................................................29 Treasure Island .............................................................................30 Cyprus at the turn of the 20th ......................................................35 Glyn Hughes ................................................................................37 Digital Corpus ..............................................................................38 Unknown history .........................................................................40 Europa Nostra ..............................................................................50 Arshak Sarkissian ........................................................................51 I am not the cancer ......................................................................54 Soprano Tereza Gevorgyan ........................................................58 This is Italy ...................................................................................59 -

Eтнолошко-Антропoлошке Свеске 19, (Н.С.) 8 (2012)

Оригинални научни рад УДК:793.3:316.7(495.9)(091) Maria Hnaraki [email protected] Cretan Identity through its Dancing History Apstract: Dances are threads that have fashioned the fabric of Cretan society since ancient times. Histories are being performed to show the concrete links between past and present and are thus transformed into living communal memories which constitute a rich source of knowledge and identity, speaking for a poetics of Cretanhood. Key words: Crete, identity, dance, mytho-musicology, dancing history Prelude Crete, a Mediterranean island, serves as a connecting link between the so-called East and West. Located at the crossroads between three conti- nents, Europe, Africa and Asia, Crete has also embraced many influences (such as Arab, Venetian, and Turkish). Its forms of musical expression ha- ve been interpreted historically and connected to the fight, the resistance and the numerous rebellions against the Turks (particularly in reference to what is widely perceived in Greece as a “tainted” Ottoman past), who lan- ded on the island in 1645, conquered it in 1669 and controlled it until 1898. In more recent times, an active resistance was raised against the Ger- man invasion during the Second World War. During such periods, in order to claim their land, Cretans sang and danced (Hnaraki 2011, forthcoming). Cretan dances function as threads that have fashioned the fabric of Cre- tan society since ancient times, providing authentic evidence of the continu- ity of Crete’s popular tradition and rhythm. Despite modernization, which can be found in many places all over Greece and Crete, especially nowadays, dance is still a common means of expression for most Cretan people (Hnara- ki 1998, 63). -

Authentic Chania, a Travel Rich in Experiences

Authentic Chania, a travel rich in experiences Plan Days 5 Experience both the bustling city and the more quiet local hangouts, visit unique places of the province and enjoy wonderful moments of relaxation in one of the houses of Althea maisonettes! By: Wondergreece Traveler PLAN SUMMARY Day 1 1. Chania International Airport “Ioannis Daskalogiannis” About region/Access & Useful info 2. Althea Maisonettes Accommodation 3. Chania About region/Main cities & villages 4. Venetian harbor of Chania Culture/Monuments & sights 5. Adespoto music taverna Food, Shops & Rentals/Food 6. Althea Maisonettes Accommodation Day 2 1. Althea Maisonettes Accommodation 2. Ancient Aptera Culture/Archaelogical sites 3. Itzedin Fortress Culture/Castles 4. Kalami Nature/Beaches 5. Kalyves Nature/Beaches 6. Althea Maisonettes Accommodation Day 3 1. Althea Maisonettes Accommodation 2. Almyrida Nature/Beaches 3. Vamos About region/Main cities & villages 4. Agios Georgios Monastery Culture/Churches & Monasteries 5. Vryses About region/Main cities & villages 6. Dourakis Winery Local Products & Gastronomy/Wineries 7. Althea Maisonettes Accommodation Day 4 1. Althea Maisonettes Accommodation WonderGreece.gr - Bon Voyage 1 2. Beach of Georgioupolis Nature/Beaches 3. Kournas Lake Nature/Lakes 4. Argyroupolis About region/Main cities & villages 5. Argyroupolis Waterfalls Nature/Waterfalls 6. Rethymno About region/Main cities & villages 7. Althea Maisonettes Accommodation Day 5 1. Althea Maisonettes Accommodation 2. Koum Kapi Culture/Monuments & sights 3. Halepa district Culture/Monuments & sights 4. Tampakaria Culture/Monuments & sights 5. Ble Food, Shops & Rentals/Food 6. The Venizelos' Tombs Culture/Monuments & sights 7. Kalathas Nature/Beaches 8. Chania International Airport “Ioannis Daskalogiannis” About region/Access & Useful info WonderGreece.gr - Bon Voyage 2 Day 1 1.