Heraklion and Chania: a Study of the Evolution of Their Spatial and Functional Patterns

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biological Warfare Plan in the 17Th Century—The Siege of Candia, 1648–1669 Eleni Thalassinou, Costas Tsiamis, Effie Poulakou-Rebelakou, Angelos Hatzakis

HISTORICAL REVIEW Biological Warfare Plan in the 17th Century—the Siege of Candia, 1648–1669 Eleni Thalassinou, Costas Tsiamis, Effie Poulakou-Rebelakou, Angelos Hatzakis A little-known effort to conduct biological warfare oc- to have hurled corpses of plague victims into the besieged curred during the 17th century. The incident transpired city (9). During World War II, Japan conducted biological during the Venetian–Ottoman War, when the city of Can- weapons research at facilities in China. Prisoners of war dia (now Heraklion, Greece) was under siege by the Otto- were infected with several pathogens, including Y. pestis; mans (1648–1669). The data we describe, obtained from >10,000 died as a result of experimental infection or execu- the Archives of the Venetian State, are related to an op- tion after experimentation. At least 11 Chinese cities were eration organized by the Venetian Intelligence Services, which aimed at lifting the siege by infecting the Ottoman attacked with biological agents sprayed from aircraft or in- soldiers with plague by attacking them with a liquid made troduced into water supplies or food products. Y. pestis–in- from the spleens and buboes of plague victims. Although fected fleas were released from aircraft over Chinese cities the plan was perfectly organized, and the deadly mixture to initiate plague epidemics (10). We describe a plan—ul- was ready to use, the attack was ultimately never carried timately abandoned—to use plague as a biological weapon out. The conception and the detailed cynical planning of during the Venetian–Ottoman War in the 17th century. the attack on Candia illustrate a dangerous way of think- ing about the use of biological weapons and the absence Archival Sources of reservations when potential users, within their religious Our research has been based on material from the Ar- framework, cast their enemies as undeserving of humani- chives of the Venetian State (11). -

Crete 8 Days

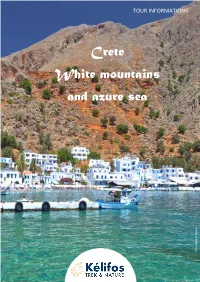

TOUR INFORMATIONS Crete White mountains and azure sea The village of Loutro village The SUMMARY Greece • Crete Self guided hike 8 days 7 nights Itinerant trip Nothing to carry 2 / 5 CYCLP0001 HIGHLIGHTS Chania: the most beautiful city in Crete The Samaria and Agia Irini gorges A good mix of walking, swimming, relaxation and visits of sites www.kelifos.travel +30 698 691 54 80 • [email protected] • CYCGP0018 1 / 13 MAP www.kelifos.travel +30 698 691 54 80 • [email protected] • CYCGP0018 2 / 13 P R O P O S E D ITINERARY Wild, untamed ... and yet so welcoming. Crete is an island of character, a rebellious island, sometimes, but one that opens its doors wide before you even knock. Crete is like its mountains, crisscrossed by spectacular gorges tumbling down into the sea of Libya, to the tiny seaside resorts where you will relax like in a dream. Crete is the quintessence of the alliance between sea and mountains, many of which exceed 2000 meters, especially in the mountain range of Lefka Ori, (means White mountains in Greek - a hint to the limestone that constitutes them) where our hike takes place. Our eight-day tour follows a part of the European E4 trail along the south-west coast of the island with magnificent forays into the gorges of Agia Irini and Samaria for the island's most famous hike. But a nature trip in Crete cannot be confined to a simple landscape discovery even gorgeous. It is in fact associate with exceptional cultural discoveries. The beautiful heritage of Chania borrows from the Venetian and Ottoman occupants who followed on the island. -

A Venetian Rural Villa in the Island of Crete. Traditional and Digital Strategies for a Heritage at Risk Emma Maglio

A Venetian rural villa in the island of Crete. Traditional and digital strategies for a heritage at risk Emma Maglio To cite this version: Emma Maglio. A Venetian rural villa in the island of Crete. Traditional and digital strategies for a heritage at risk. Digital Heritage 2013, Oct 2013, Marseille, France. pp.83-86. halshs-00979215 HAL Id: halshs-00979215 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00979215 Submitted on 15 Apr 2014 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A Venetian rural villa in the island of Crete. Traditional and digital strategies for a heritage at risk Emma Maglio Aix-Marseille University LA3M (UMR 7298-CNRS), LabexMed Aix-en-Provence, France [email protected] Abstract — The Trevisan villa, an example of rural built rather they were regarded with indifference or even hostility»3. heritage in Crete dating back to the Venetian period, was the These ones were abandoned or demolished and only recently, object of an architectural and archaeological survey in order to especially before Greece entered the EU, remains of Venetian study its typology and plan transformations. Considering its heritage were recognized in their value: but academic research ruined conditions and the difficulties in ensuring its protection, a and conservation practices slowly develop. -

Memorial Services

BATTLE OF CRETE COMMEMORATIONS ATHENS & CRETE, 12-21 MAY 2019 MEMORIAL SERVICES Sunday, 12 May 2019 10.45 – Commemorative service at the Athens Metropolitan Cathedral and wreath-laying at the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Syntagma Square Location: Mitropoleos Street - Syntagama Square, Athens Wednesday, 15 May 2019 08.00 – Flag hoisting at the Unknown Soldier Memorial by the 547 AM/TP Regiment Location: Square of the Unknown Soldier (Platia Agnostou Stratioti), Rethymno town Friday, 17 May 2019 11.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Army Cadets Memorial Location: Kolymbari, Region of Chania 11.30 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the 110 Martyrs Memorial Location: Missiria, Region of Rethymno Saturday, 18 May 2019 10.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Memorial to the Fallen Greeks Location: Latzimas, Rethymno Region 11.30 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Australian-Greek Memorial Location: Stavromenos, Region of Rethymno 13.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Greek-Australian Memorial | Presentation of RSL National awards to Cretan students Location: 38, Igoumenou Gavriil Str. (Efedron Axiomatikon Square), Rethymno town 18.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Memorial to the Fallen Inhabitants Location: 1, Kanari Coast, Nea Chora harbour, Chania town 1 18.00 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Memorial to the Fallen & the Bust of Colonel Stylianos Manioudakis Location: Armeni, Region of Rethymno 19.30 – Commemorative service and wreath-laying at the Peace Memorial for Greeks and Allies Location: Preveli, Region of Rethymno Sunday, 19 May 2019 10.00 – Official doxology Location: Presentation of Mary Metropolitan Church, Rethymno town 11.00 – Memorial service and wreath-laying at the Rethymno Gerndarmerie School Location: 29, N. -

Registration Certificate

1 The following information has been supplied by the Greek Aliens Bureau: It is obligatory for all EU nationals to apply for a “Registration Certificate” (Veveosi Engrafis - Βεβαίωση Εγγραφής) after they have spent 3 months in Greece (Directive 2004/38/EC).This requirement also applies to UK nationals during the transition period. This certificate is open- dated. You only need to renew it if your circumstances change e.g. if you had registered as unemployed and you have now found employment. Below we outline some of the required documents for the most common cases. Please refer to the local Police Authorities for information on the regulations for freelancers, domestic employment and students. You should submit your application and required documents at your local Aliens Police (Tmima Allodapon – Τμήμα Αλλοδαπών, for addresses, contact telephone and opening hours see end); if you live outside Athens go to the local police station closest to your residence. In all cases, original documents and photocopies are required. You should approach the Greek Authorities for detailed information on the documents required or further clarification. Please note that some authorities work by appointment and will request that you book an appointment in advance. Required documents in the case of a working person: 1. Valid passport. 2. Two (2) photos. 3. Applicant’s proof of address [a document containing both the applicant’s name and address e.g. photocopy of the house lease, public utility bill (DEH, OTE, EYDAP) or statement from Tax Office (Tax Return)]. If unavailable please see the requirements for hospitality. 4. Photocopy of employment contract. -

Greece • Crete • Turkey May 28 - June 22, 2021

GREECE • CRETE • TURKEY MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 Tour Hosts: Dr. Scott Moore Dr. Jason Whitlark organized by GREECE - CRETE - TURKEY / May 28 - June 22, 2021 May 31 Mon ATHENS - CORINTH CANAL - CORINTH – ACROCORINTH - NAFPLION At 8:30a.m. depart from Athens and drive along the coastal highway of Saronic Gulf. Arrive at the Corinth Canal for a brief stop and then continue on to the Acropolis of Corinth. Acro-corinth is the citadel of Corinth. It is situated to the southwest of the ancient city and rises to an elevation of 1883 ft. [574 m.]. Today it is surrounded by walls that are about 1.85 mi. [3 km.] long. The foundations of the fortifications are ancient—going back to the Hellenistic Period. The current walls were built and rebuilt by the Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Ottoman Turks. Climb up and visit the fortress. Then proceed to the Ancient city of Corinth. It was to this megalopolis where the apostle Paul came and worked, established a thriving church, subsequently sending two of his epistles now part of the New Testament. Here, we see all of the sites associated with his ministry: the Agora, the Temple of Apollo, the Roman Odeon, the Bema and Gallio’s Seat. The small local archaeological museum here is an absolute must! In Romans 16:23 Paul mentions his friend Erastus and • • we will see an inscription to him at the site. In the afternoon we will drive to GREECE CRETE TURKEY Nafplion for check-in at hotel followed by dinner and overnight. (B,D) MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 June 1 Tue EPIDAURAUS - MYCENAE - NAFPLION Morning visit to Mycenae where we see the remains of the prehistoric citadel Parthenon, fortified with the Cyclopean Walls, the Lionesses’ Gate, the remains of the Athens Mycenaean Palace and the Tomb of King Agamemnon in which we will actually enter. -

FLOWAID-Crete-Workshop Ierapetra-Nov-2008-Small

FLOW-AID Workshop Proceedings Ierapetra (Crete) (7 th Nov, 2008) 1/33 SIXTH FRAMEWORK PROGRAMME FP6-2005-Global-4, Priority II.3.5 Water in Agriculture: New systems and technologies for irrigation and drainage Farm Level Optimal Water management: Assistant for Irrigation under Deficit Contract no.: 036958 Proceedings of the FLOW-AID workshop in Ierapetra (Crete, Greece) Date: November 7 th , 2008 Project coordinator name: J. Balendonck Project coordinator organisation name: Wageningen University and Research Center Plant Research International Contributions from: Jos Balendonck, PRI – Wageningen (NL) (editor) Nick Sigrimis, Prof Mechanics and Automation – AUA (co-editor, organizer) Frank Kempkes, PRI-Wageningen (NL) Richard Whalley, RRES (UK) Yuksel Tuzel, Ege University – Izmir (Turkey) Luca Incrocci, University of Pisa (Italy) Revision: final Dissemination level: PUBLIC Project co-funded by the European Commission within the Sixth Framework Programme (2002-2006) FLOW-AID Workshop Proceedings Ierapetra (Crete) (7 th Nov, 2008) 2/33 Contents Contents .................................................................................................................................... 2 FLOW-AID WORKSHOP ........................................................................................................... 3 Technical Tour & Ierapetra Conference ..................................................................................... 4 Farm Level Optimal Water management: Assistant for Irrigation under Deficit (FLOW-AID) ...... 7 OBJECTIVES........................................................................................................................ -

Cretan Salad with Cucumber, Tomato, Onion, Pepper, Boiled

We serve bread with a selection of dips at a charge of ............... per person. Please kindly inform the waiter if you prefer not to have this served to you. για χορτοφάγους / vegetarian χωρίς γλουτένη / gluten free * κατεψυγμένο / frοzen Σαλάτες Salads Κρητική ντομάτα, αγγούρι, κρεμμύδι, πιπεριά, πατάτα, παξιμάδι χαρουπιού, αλατσολιές, πηχτόγαλο Χανίων, αρίγανη, λάδι μυρωδικών και κρίταμο Cretan salad with cucumber, tomato, onion, pepper, boiled potatoes, carob rusk, olives, white soft cheese, oregano, cretan herbs oil and kritamo Kretische, Tomaten, Gurken, Zwiebeln, Paprika, Kartoffeln, Johannisbrotkerne, oliven, Chania-Quark, Argan, Gewürzöl und Kritamo Cretense tomate, pepino, cebolla, pimiento verde, patata, biscotes de algarroba, aceitunas negras “saladas”, “leche espesa” de Chania, orégano, aceite de hierbas y perejil de mar Crétois tomate, concombre, oignon, poivron, pomme de terre, noix de caroube, olives, caillé de Chania, argan, huile d’épice et kritamo Kretensisk salat med tomat, agurk, løg, peberfrugt, kartoffel, hårdt brød af johannesbrødmel, saltede oliven, hvid ost, oregano, krydderolie og strandfennikel Insalata cretese con pomodoro, cetriolo, cipolla, peperone, patata, fette biscottata di carrube, olives, fortaggio bianco morbido, origano, olio alle erbe e finocchio marino Критский Салат Πомидор, огурец, лук, вареная картошка, сухари рожкового дерева, оливки, белый мягкий сыр, орегано, ароматное оливковое масло, трава критамо ........ 8.20 Ντάκος «Αρισμαρί» με μους μυζήθρας, φρεσκοτριμμένη ντομάτα, πολύχρωμα ντοματίνια, -

Table of Contents 1

Maria Hnaraki, 1 Ph.D. Mentor & Cultural Advisor Drexel University (Philadelphia-U.S.A.) Associate Teaching Professor Official Representative of the World Council of Cretans Kids Love Greece Scientific & Educational Consultant Tel: (+) 30-6932-050-446 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Table of Contents 1. FORMAL EDUCATION ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 2. ADDITIONAL EDUCATION .............................................................................................................................................................. 2 3. EMPLOYMENT RECORD ................................................................................................................................................................... 2 3.1. Current Status (2015-…) ................................................................................................................................................................. 2 3.2. Employment History ....................................................................................................................................................................... 3 3.2.1. Teaching Experience ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 3.2.2. Research Projects .................................................................................................................................................................... -

Heraklion (Greece)

Research in the communities – mapping potential cultural heritage sites with potential for adaptive re-use – Heraklion (Greece) The island of Crete in general and the city of Heraklion has an enormous cultural heritage. The Arab traders from al-Andalus (Iberia) who founded the Emirate of Crete moved the island's capital from Gortyna to a new castle they called rabḍ al-ḫandaq in the 820s. This was Hellenized as Χάνδαξ (Chándax) or Χάνδακας (Chándakas) and Latinized as Candia, the Ottoman name was Kandiye. The ancient name Ηράκλειον was revived in the 19th century and comes from the nearby Roman port of Heracleum ("Heracles's city"), whose exact location is unknown. English usage formerly preferred the classicizing transliterations "Heraklion" or "Heraclion", but the form "Iraklion" is becoming more common. Knossos is located within the Municipality of Heraklion and has been called as Europe's oldest city. Heraklion is close to the ruins of the palace of Knossos, which in Minoan times was the largest centre of population on Crete. Knossos had a port at the site of Heraklion from the beginning of Early Minoan period (3500 to 2100 BC). Between 1600 and 1525 BC, the port was destroyed by a volcanic tsunami from nearby Santorini, leveling the region and covering it with ash. The present city of Heraklion was founded in 824 by the Arabs under Abu Hafs Umar. They built a moat around the city for protection, and named the city rabḍ al-ḫandaq, "Castle of the Moat", Hellenized as Χάνδαξ, Chandax). It became the capital of the Emirate of Crete (ca. -

Hike Along the Libyan Sea in Crete, Greece May 15 - 26, 2022 $2,850* Per Person Sharing Twin/Bath, $450 Single Supplement

Hiking Adventures Hike along the Libyan Sea in Crete, Greece May 15 - 26, 2022 $2,850* per person sharing twin/bath, $450 single supplement A few years ago, we fell in love with Crete, especially its wild western part. Steep cliffs rise above lonely beaches with crystal clear water, white- washed churches and small villages dot the arid hillsides where the scent of pungent plants perfume the air. This trip offers a chance to spend time in historic Chania, visit the Minoan Palace in Heraklion where the Minotaur once roamed, and, best of all, hike part of the E4 long distance trail along Europe’s southernmost coast facing the Libyan Sea. This is not for the faint of heart as some of the hikes are on exposed, steep trails, and we would rate some of the hikes as strenous. *The tour cost includes all accommodation in twin bedded rooms in hotels and pensions, breakfast and dinner daily, all transfers in Crete, luggage transfers from day 7 - 11, 2 leaders, taxes and service charges. Air transportation to and from Crete is not included. For those who would like to visit Athens before our hike on Crete, an optional program is available (shown in italics). Optional Prelude in Athens: $638 per person sharing twin/bath Thursday, May 12, 2022: Arrive at Athens airport. You are met at the airport and transferred by private car to a centrally located hotel. Friday, May 13, 2022: Full day at leisure to explore Athens. (B) Sunrise Travel ◾ 22891 Via Fabricante Suite 603 ◾ Mission Viejo CA 92691 ◾ CST 1005170-10 ◾ 949.837.0620 ◾ sunriseteam.com GR22itinerary: Updated 4/29/2021EM Saturday, May 14, 2022: in Athens, night ferry to Crete Day at leisure in Athens. -

Domes Noruz Chania Privacy Policy Statement Preface. DOMES OF

Domes Noruz Chania Privacy Policy Statement Preface. DOMES OF CHANIA SA runs DOMES NORUZ CHANIA Hotel at Daratsos Crete, Agioi Apostoloi Region, Nea Kudonia. Domes of Chania SA is established in Greece, Elounda Residential Area, Tsifliki Region, Agios Nikolaos, Lasithi, Crete (Registration Number 133789341000) is the Controller of your Personal Data and in compliance with the Regulation EU 2016/679 of the European Parliament and the Council of 27 April 2016 applicable from 25 May 2018 renewed its privacy rules in order to achieve the most secure and safe data processing way. Article 1. Definitions 1.1. «personal data» means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person (data subject) in particular by reference to an identifier such asname, gender, postal address, telephone number, email address, credit or debit card number other financial information in limited circumstances, language preference, date and place of birth, nationality, passport, visa or other government-issued identification data, important dates, such as birthdays, anniversaries and special occasion, membership or loyalty program data (including co-branded payment cards, travel partner program affiliations), employer details, travel itinerary, tour group or activity data, prior guest stays or interactions, goods and services purchased, special service and amenity requests, geolocation information, social media account ID, profile photo and other data publicly available, or data made available by linking your social media and loyalty accounts. «personal data» means also data about family members and companions, such as names and ages of children, biometric data, such as digital images, images and video and audio data via security cameras located in public areas, such as hallways and lobbies, in our properties.