Modality and Diversity in Cretan Music by Michael Hagleitner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biological Warfare Plan in the 17Th Century—The Siege of Candia, 1648–1669 Eleni Thalassinou, Costas Tsiamis, Effie Poulakou-Rebelakou, Angelos Hatzakis

HISTORICAL REVIEW Biological Warfare Plan in the 17th Century—the Siege of Candia, 1648–1669 Eleni Thalassinou, Costas Tsiamis, Effie Poulakou-Rebelakou, Angelos Hatzakis A little-known effort to conduct biological warfare oc- to have hurled corpses of plague victims into the besieged curred during the 17th century. The incident transpired city (9). During World War II, Japan conducted biological during the Venetian–Ottoman War, when the city of Can- weapons research at facilities in China. Prisoners of war dia (now Heraklion, Greece) was under siege by the Otto- were infected with several pathogens, including Y. pestis; mans (1648–1669). The data we describe, obtained from >10,000 died as a result of experimental infection or execu- the Archives of the Venetian State, are related to an op- tion after experimentation. At least 11 Chinese cities were eration organized by the Venetian Intelligence Services, which aimed at lifting the siege by infecting the Ottoman attacked with biological agents sprayed from aircraft or in- soldiers with plague by attacking them with a liquid made troduced into water supplies or food products. Y. pestis–in- from the spleens and buboes of plague victims. Although fected fleas were released from aircraft over Chinese cities the plan was perfectly organized, and the deadly mixture to initiate plague epidemics (10). We describe a plan—ul- was ready to use, the attack was ultimately never carried timately abandoned—to use plague as a biological weapon out. The conception and the detailed cynical planning of during the Venetian–Ottoman War in the 17th century. the attack on Candia illustrate a dangerous way of think- ing about the use of biological weapons and the absence Archival Sources of reservations when potential users, within their religious Our research has been based on material from the Ar- framework, cast their enemies as undeserving of humani- chives of the Venetian State (11). -

Crete 8 Days

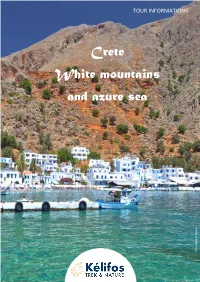

TOUR INFORMATIONS Crete White mountains and azure sea The village of Loutro village The SUMMARY Greece • Crete Self guided hike 8 days 7 nights Itinerant trip Nothing to carry 2 / 5 CYCLP0001 HIGHLIGHTS Chania: the most beautiful city in Crete The Samaria and Agia Irini gorges A good mix of walking, swimming, relaxation and visits of sites www.kelifos.travel +30 698 691 54 80 • [email protected] • CYCGP0018 1 / 13 MAP www.kelifos.travel +30 698 691 54 80 • [email protected] • CYCGP0018 2 / 13 P R O P O S E D ITINERARY Wild, untamed ... and yet so welcoming. Crete is an island of character, a rebellious island, sometimes, but one that opens its doors wide before you even knock. Crete is like its mountains, crisscrossed by spectacular gorges tumbling down into the sea of Libya, to the tiny seaside resorts where you will relax like in a dream. Crete is the quintessence of the alliance between sea and mountains, many of which exceed 2000 meters, especially in the mountain range of Lefka Ori, (means White mountains in Greek - a hint to the limestone that constitutes them) where our hike takes place. Our eight-day tour follows a part of the European E4 trail along the south-west coast of the island with magnificent forays into the gorges of Agia Irini and Samaria for the island's most famous hike. But a nature trip in Crete cannot be confined to a simple landscape discovery even gorgeous. It is in fact associate with exceptional cultural discoveries. The beautiful heritage of Chania borrows from the Venetian and Ottoman occupants who followed on the island. -

Registration Certificate

1 The following information has been supplied by the Greek Aliens Bureau: It is obligatory for all EU nationals to apply for a “Registration Certificate” (Veveosi Engrafis - Βεβαίωση Εγγραφής) after they have spent 3 months in Greece (Directive 2004/38/EC).This requirement also applies to UK nationals during the transition period. This certificate is open- dated. You only need to renew it if your circumstances change e.g. if you had registered as unemployed and you have now found employment. Below we outline some of the required documents for the most common cases. Please refer to the local Police Authorities for information on the regulations for freelancers, domestic employment and students. You should submit your application and required documents at your local Aliens Police (Tmima Allodapon – Τμήμα Αλλοδαπών, for addresses, contact telephone and opening hours see end); if you live outside Athens go to the local police station closest to your residence. In all cases, original documents and photocopies are required. You should approach the Greek Authorities for detailed information on the documents required or further clarification. Please note that some authorities work by appointment and will request that you book an appointment in advance. Required documents in the case of a working person: 1. Valid passport. 2. Two (2) photos. 3. Applicant’s proof of address [a document containing both the applicant’s name and address e.g. photocopy of the house lease, public utility bill (DEH, OTE, EYDAP) or statement from Tax Office (Tax Return)]. If unavailable please see the requirements for hospitality. 4. Photocopy of employment contract. -

Greece • Crete • Turkey May 28 - June 22, 2021

GREECE • CRETE • TURKEY MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 Tour Hosts: Dr. Scott Moore Dr. Jason Whitlark organized by GREECE - CRETE - TURKEY / May 28 - June 22, 2021 May 31 Mon ATHENS - CORINTH CANAL - CORINTH – ACROCORINTH - NAFPLION At 8:30a.m. depart from Athens and drive along the coastal highway of Saronic Gulf. Arrive at the Corinth Canal for a brief stop and then continue on to the Acropolis of Corinth. Acro-corinth is the citadel of Corinth. It is situated to the southwest of the ancient city and rises to an elevation of 1883 ft. [574 m.]. Today it is surrounded by walls that are about 1.85 mi. [3 km.] long. The foundations of the fortifications are ancient—going back to the Hellenistic Period. The current walls were built and rebuilt by the Byzantines, Franks, Venetians, and Ottoman Turks. Climb up and visit the fortress. Then proceed to the Ancient city of Corinth. It was to this megalopolis where the apostle Paul came and worked, established a thriving church, subsequently sending two of his epistles now part of the New Testament. Here, we see all of the sites associated with his ministry: the Agora, the Temple of Apollo, the Roman Odeon, the Bema and Gallio’s Seat. The small local archaeological museum here is an absolute must! In Romans 16:23 Paul mentions his friend Erastus and • • we will see an inscription to him at the site. In the afternoon we will drive to GREECE CRETE TURKEY Nafplion for check-in at hotel followed by dinner and overnight. (B,D) MAY 28 - JUNE 22, 2021 June 1 Tue EPIDAURAUS - MYCENAE - NAFPLION Morning visit to Mycenae where we see the remains of the prehistoric citadel Parthenon, fortified with the Cyclopean Walls, the Lionesses’ Gate, the remains of the Athens Mycenaean Palace and the Tomb of King Agamemnon in which we will actually enter. -

Paleochora: Wie Das Dorf Zu Seinem Namen Kam

Paleochora: Wie das Dorf zu seinem Namen kam. Gute Quelle: Das Buch „Paleochora (Ein Rückblick in die Vergangenheit)“, von Nikolaos Pyrovolakis. Seit der venezianischen Epoche hieß das Gebiet des heutigen Paleochoras „Selino Kastelli“ – und zwar aufgrund des venezianischen Kastells, das sich oberhalb des heutigen Hafens befindet. Die Bezeichnung dieses Kastells gab dem ganzen Bezirk, der zuvor „Orima“ (= „in den Bergen liegend“) hieß, den Namen Selino. Ein schönes Buch. Gibt es nur im Buchladen von Paleochora. 1834 besichtigte der englische Reisende Robert Pashley* die venezianische Festung und berichtete, dass er um diese herum nur auf Ruinen gestoßen und der Ort vollkommen unbewohnt gewesen sei. Es gab nur ein Gebäude (Lager), in dem man Getreide aufbewahrte, das hauptsächlich aus Chania kam. Dieses Getreide diente der Versorgung der Bewohner von Selino und Sfakia. Während seines Besuches im heutigen Paleochora 1834 weist er auf die Überreste einer alten Stadt hin und wird wörtlich wie folgt zitiert: „Nachdem wir um Viertel nach Neun von Selino Kastelli weggegangen waren, überquerten wir den Fluss, der eine halbe Meile östlich liegt. Der Boden rundum ist von Tonscherben bedeckt. Das einzige Material, das auf die Existenz einer antiken Stadt hindeutet.“ Es gibt auch verschiedene Hinweise darauf, dass alte Bewohner Paleochoras an dieser Stelle beim Pflügen auf verschiedene Münzen gestoßen sind. Der Reisende Paul Faure* geht ganz klar davon aus, dass die Ortschaft wahrscheinlich auf den Trümmern der antiken Stadt „Kalamidi“ erbaut worden ist. Da also Paleochora in der Nähe einer antiken, zerfallenen Stadt wiedererbaut wurde, wurde ihm dieser Ortsname gegeben. Es stellt sich jetzt die Frage, welche von den 40 Städten, die Plinius niedergeschrieben hat, es ist. -

Table of Contents 1

Maria Hnaraki, 1 Ph.D. Mentor & Cultural Advisor Drexel University (Philadelphia-U.S.A.) Associate Teaching Professor Official Representative of the World Council of Cretans Kids Love Greece Scientific & Educational Consultant Tel: (+) 30-6932-050-446 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected] Table of Contents 1. FORMAL EDUCATION ....................................................................................................................................................................... 2 2. ADDITIONAL EDUCATION .............................................................................................................................................................. 2 3. EMPLOYMENT RECORD ................................................................................................................................................................... 2 3.1. Current Status (2015-…) ................................................................................................................................................................. 2 3.2. Employment History ....................................................................................................................................................................... 3 3.2.1. Teaching Experience ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 3.2.2. Research Projects .................................................................................................................................................................... -

Manual English.Pdf

In 1094 the Greek Emperor Alexius I asked Pope Urban II for aid. Turkish armies had overrun the Eastern provinces of the Greek empire empire and were getting close to the capital, Constantinople. The Pope appealed to Western European knights to put their differences and petty squabbles aside and help the Greeks in the east. He summoned them together to take part in a Holy War that would also serve as a pilgrimage to Jersalem. The first Crusade would soon begin. 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 5.3 The Mercenary Post . .35 1.0 GETTING STARTED . .4 5.4 Available Units . .35 4. noitallatsnI dna stnemeriuqeR metsyS 1.1 metsyS stnemeriuqeR dna . noitallatsnI . 4. 5.5 Gathering your Forces . .38 5. .sedoM emaG dna emaG eht gnitratS 2.1 gnitratS eht emaG dna emaG .sedoM . 5. 5.6 Marching Orders . .39 1.3 Game Options . .6 5.7 Changing your Units Stance. .39 1.4 Game Overview . .7 5.8 Military Commands. .40 1.5 About t eh .launaM . .. 7. 5.9 Map Bookmarks . .42 1.6 Winning and Losing. .8 1.7 Playing a Multiplayer Game. .9 6.0 DEFENDING YOU R P EOPLE . .42 1.8 Map Editor Overview. .11 6.1 The Gatehouse. .42 1.9 Crusader Games. .12 6.2 Building High and Low Walls . .43 6.3 Turrets and Towers . .43 2.0 GAME B ASICS . .15 6.4 Placing Stairs . .44 2.1 Main Screen Overview and Navigating the Map . .15 6.5 Traps . .44 2.2 Camera Interface. .15 6.6 Moat Digging . .44 2.3 Placing your Keep. -

PANAYOTIS F. LEAGUE Curriculum Vitae Harvard University Music

PANAYOTIS F. LEAGUE Curriculum Vitae Harvard University Music Department 3 Oxford Street Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 617.999.6364 [email protected] EDUCATION 2017 PhD, Music Department (Ethnomusicology), Harvard University Dissertation: “Echoes of the Great Catastrophe: Re-Sounding Anatolian Greekness in Diaspora” Advisors: Kay Shelemay and Richard Wolf 2012 M.A., Department of Musicology and Ethnomusicology (Ethnomusicology), Boston University 2008 B.A. (with Highest Distinction), Classics and Modern Greek Studies, Hellenic College PROFESSIONAL APPOINTMENTS 2019 Florida State University, Assistant Professor of Ethnomusicology 2019 Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, Harvard University Associate for the James A. Notopoulos Collection 2019 (Summer) Paraíba State University, João Pessoa, Brazil Visiting Assistant Professor of Ethnomusicology (via Fulbright U.S. Scholar Award) 2019 (Spring) Harvard University, Lecturer in Music 2018-2019 Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Lecturer in Music 2018 Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, Harvard University Milman Parry Collection Fellow 2018 Managing Editor, Oral Tradition 2017 Milman Parry Collection of Oral Literature, Harvard University James A. Notopoulos Fellow League, 2 2017 Harvard University, Departmental Teaching Fellow in Music LANGUAGES Fluent: English, Greek, Portuguese Reading proficiency: Spanish, French, Italian, Ancient Greek, Latin, Turkish, Irish Gaelic Learning: Yoruba, Tupi-Guarani HONORS AND AWARDS 2018 Traditional Artist Fellowship, Massachusetts Cultural Council 2016 Professor of the Year Award, Hellenic College 2015 Harvard University Derek Bok Center for Teaching and Learning Certificate of Distinction in Teaching for “Introduction to Tonal Music I” 2015 Victor Papacosma Best Graduate Student Essay Prize, Modern Greek Studies Association, for “The Poetics of Meráki: Dialogue and Speech Genre in Kalymnian Song” 2015 James T. -

Ferals, My Little «Ἀγρίμια Κι΄Ἀγριμάκια Μου ΄Λάφια Μου ΄Μερωμένα Πεστέ

Greek Song No5 – Agrimia Ki Agrimakia Mou https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jiNrWFUKdho The music of Crete (Greek: Κρητική μουσική), also called kritika (Greek: κρητικά), refers to traditional forms of Greek folk music prevalent on the island of Crete in Greece. Cretan music is the eldest music in Greece and generally, in Europe. Since ancient times, music held a special place in Crete and this is proved by the archaeological excavations, the ancient texts and paintings that are preserved in the Archaeological Museum of Heraklion. Most paintings represent the lyre player playing in the middle and the dancers dancing around in circle. There are also images of flutes, conches, trumpets and the ancient lyre. Lyra is the basic instrument of Cretan music. It is in three types: “Lyraki” (small lyre), the common lyre and “Vrontolyra”. They have three metallic chords, which, in the past were made of intestine. They differ in size, the sound they produce and their use. Cretan traditional music includes instrumental music (generally also involving singing), a capella songs known as the rizitika, "Erotokritos," Cretan urban songs (tabachaniotika), as well as other miscellaneous songs and folk genres (lullabies, ritual laments, etc.). “Rizitika” is a category of Cretan songs, named from the Greek word “riza” which means “root”. Therefore these songs date back many centuries ago in Cretan music. Cretans don’t dance these particular songs. The singer usually sings them and the chorus repeats the lyrics. One of the most famous Rizitika song is “ Agrimia Ki Agrimakia Mou” (Ferals, my little ferals) and especially its version by the mst famous Cretan singers of all time Nikos Xyloyris. -

Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 12-1992 Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance Leon Stratikis University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss Part of the Modern Languages Commons Recommended Citation Stratikis, Leon, "Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance. " PhD diss., University of Tennessee, 1992. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_graddiss/2521 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation written by Leon Stratikis entitled "Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance." I have examined the final electronic copy of this dissertation for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, with a major in Modern Foreign Languages. Paul Barrette, Major Professor We have read this dissertation and recommend its acceptance: James E. Shelton, Patrick Brady, Bryant Creel, Thomas Heffernan Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a dissertation by Leon Stratikis entitled Byzantium and France: the Twelfth Century Renaissance and the Birth of the Medieval Romance. -

Texas Camp Is Almost Here! TIFD Board Elections Are Coming

November 2012–January 2013 Volume 32, Issue 4 News www.tifd.org Inside this Issue: Texas Camp Is Almost Here! The deadline for Texas Camp registration is November 8. Come and In Memory of Jo Soto 2 learn Bulgarian dances from Yuliyan Yordanov! See our traditional floor TIFD Board of Directors 2 in a new location! Shop at the Balkan Bazaar! Wear interesting costumes Next Board Meeting 2 for the parties (Thursday: Time Machine; Friday; Bulgaria’s neighbors; Saturday: Bulgaria)! Meet interesting people and dance with them! Calendar of Events 3 Travel Opportunities 3 News from Local Groups 4 Houston IFD 4 Tulsa IFD 4 Oklahoma City IFD 4 Austin IFD 5 Jonče Hristovski 6 Statements from TIFD Board Candidates 7 Jan Bloom (Houston) 7 Misi Tsurikov (Austin) 7 Zorba’s Dance 7 62 Years of Folk Dancing 8 World Cultural Dance Site 8 TIFD Board Elections Are Coming TIFD has a nine-member Board of Trustees. Board members serve a three- year term, with three members elected each year. The Board normally meets four times a year to oversee TIFD operations including Texas Camp, publications, finances, and promoting folk dancing in Texas and surrounding states. Board elections are either held at Texas Camp or in December. At present, we have two candidates, Misi Tsurikov and Jan Bloom, for the three open positions on the Board. Statements from Misi and Jan are on page 7. If you have an interest in running for the Board, please email [email protected]. Page 2 November 2012–January 2013 TIFD News In Memory of Jo Soto Deadline for the next By Lissa Bengtson, Acting TIFD President issue of TIFD News is January 18 The Board of Texas International Folk Dancers is profoundly saddened by the death of TIFD Board President Jo Soto on October 12, 2012. -

FW May-June 03.Qxd

IRISH COMICS • KLEZMER • NEW CHILDREN’S COLUMN FREE Volume 3 Number 5 September-October 2003 THE BI-MONTHLY NEWSPAPER ABOUT THE HAPPENINGS IN & AROUND THE GREATER LOS ANGELES FOLK COMMUNITY Tradition“Don’t you know that Folk Music is Disguisedillegal in Los Angeles?” — WARREN C ASEY of the Wicked Tinkers THE FOLK ART OF MASKS BY BROOKE ALBERTS hy do people all over the world end of the mourning period pro- make masks? Poke two eye-holes vided a cut-off for excessive sor- in a piece of paper, hold it up to row and allowed for the resump- your face, and let your voice tion of daily life. growl, “Who wants to know?” The small mask near the cen- The mask is already working its ter at the top of the wall is appar- W transformation, taking you out of ently a rendition of a Javanese yourself, whether assisting you in channeling this Wayang Topeng theater mask. It “other voice,” granting you a new persona to dram- portrays Panji, one of the most atize, or merely disguising you. In any case, the act famous characters in the dance of masking brings the participants and the audience theater of Java. The Panji story is told in a five Alban in Oaxaca. It represents Murcielago, a god (who are indeed the other participants) into an arena part dance cycle that takes Prince Panji through of night and death, also known as the bat god. where all concerned are willing to join in the mys- innocence and adolescence up through old age.