Review of the Pagasa Tropical Cyclone Warning System

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Efficient Method for Simulating Typhoon Waves Based on A

Journal of Marine Science and Engineering Article An Efficient Method for Simulating Typhoon Waves Based on a Modified Holland Vortex Model Lvqing Wang 1,2,3, Zhaozi Zhang 1,*, Bingchen Liang 1,2,*, Dongyoung Lee 4 and Shaoyang Luo 3 1 Shandong Province Key Laboratory of Ocean Engineering, Ocean University of China, 238 Songling Road, Qingdao 266100, China; [email protected] 2 College of Engineering, Ocean University of China, 238 Songling Road, Qingdao 266100, China 3 NAVAL Research Academy, Beijing 100070, China; [email protected] 4 Korea Institute of Ocean, Science and Technology, Busan 600-011, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] (Z.Z.); [email protected] (B.L.) Received: 20 January 2020; Accepted: 23 February 2020; Published: 6 March 2020 Abstract: A combination of the WAVEWATCH III (WW3) model and a modified Holland vortex model is developed and studied in the present work. The Holland 2010 model is modified with two improvements: the first is a new scaling parameter, bs, that is formulated with information about the maximum wind speed (vms) and the typhoon’s forward movement velocity (vt); the second is the introduction of an asymmetric typhoon structure. In order to convert the wind speed, as reconstructed by the modified Holland model, from 1-min averaged wind inputs into 10-min averaged wind inputs to force the WW3 model, a gust factor (gf) is fitted in accordance with practical test cases. Validation against wave buoy data proves that the combination of the two models through the gust factor is robust for the estimation of typhoon waves. -

Typhoon Sarika

Emergency Plan of Action (EPoA) Philippines: Typhoon Sarika DREF Operation: MDRPH021 Glide n° TC-2016-000108-PHL Date of issue: 19 October 2016 Date of disaster: 16 October 2016 Operation manager: Point of contact: Patrick Elliott, operations manager Atty. Oscar Palabyab, secretary general IFRC Philippines country office Philippine Red Cross Operation start date: 16 October 2016 Expected timeframe: 3 months (to 31 January 2017) Overall operation budget: CHF 169,011 Number of people affected: 52,270 people (11,926 Number of people to be assisted: 8,000 people families) (1,600 families) Host National Society: Philippine Red Cross (PRC) is the nation’s largest humanitarian organization and works through 100 chapters covering all administrative districts and major cities in the country. It has at least 1,000 staff at national headquarters and chapter levels, and approximately one million volunteers and supporters, of whom some 500,000 are active volunteers. At chapter level, a programme called Red Cross 143, has volunteers in place to enhance the overall capacity of the National Society to prepare for and respond in disaster situations. Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation: PRC is working with the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) in this operation. The National Society also works with the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) as well as American Red Cross, Australian Red Cross, British Red Cross, Canadian Red Cross, Finnish Red Cross, German Red Cross, Japanese Red Cross Society, The Netherlands Red Cross, Norwegian Red Cross, Qatar Red Crescent Society, Spanish Red Cross, and Swiss Red Cross in-country. -

The St·Ructural Evolution Oftyphoo S

NSF/ NOAA ATM 8418204 ATM 8720488 DOD- NAVY- ONR N00014-87-K-0203 THE ST·RUCTURAL EVOLUTION OFTYPHOO S by Candis L. Weatherford SEP 2 6 1989 Pl.-William M. Gray THE STRUCTURAL EVOLUTION OF TYPHOONS By Candis L. Weatherford Department of Atmospheric Science Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO 80523 September, 1989 Atmospheric Science Paper No. 446 ABSTRACT A three phase life cycle characterizing the structural evolution of typhoons has been derived from aircraft reconnaissance data for tropical cyclones in the western North Pacific. More than 750 aircraft reconnaissance missions at 700 mb into 101 northwest Pacific typhoons are examined. The typical life cycle consists of the fol lowing: phase 1) the entire vortex wind field builds as the cyclone attains maximum intensity; phase 2) central pressure fills and maximum winds decrease in association with expanding cyclone size and strengthening of outer core winds; and phase 3) the wind field of the entire vortex decays. Nearly 700 aircraft radar reports of eyewall diameter are used to augment anal yses of the typhoon's life cycle. Eye characteristics and diameter appear to reflect the ease with which the maximum wind field intensifies. On average, an eye first appears with intensifying cyclones at 980 mb central pressure. Cyclones obtaining an eye at pressures higher than 980 mb are observed to intensify more rapidly while those whose eye initially appears at lower pressures deepen at slower rates and typ ically do not achieve as deep a central pressure. The eye generally contracts with intensification and expands as the cyclone fills, although there are frequent excep tions to this rule due to the variable nature of the eyewall size. -

Hong Kong Observatory, 134A Nathan Road, Kowloon, Hong Kong

78 BAVI AUG : ,- HAISHEN JANGMI SEP AUG 6 KUJIRA MAYSAK SEP SEP HAGUPIT AUG DOLPHIN SEP /1 CHAN-HOM OCT TD.. MEKKHALA AUG TD.. AUG AUG ATSANI Hong Kong HIGOS NOV AUG DOLPHIN() 2012 SEP : 78 HAISHEN() 2010 NURI ,- /1 BAVI() 2008 SEP JUN JANGMI CHAN-HOM() 2014 NANGKA HIGOS(2007) VONGFONG AUG ()2005 OCT OCT AUG MAY HAGUPIT() 2004 + AUG SINLAKU AUG AUG TD.. JUL MEKKHALA VAMCO ()2006 6 NOV MAYSAK() 2009 AUG * + NANGKA() 2016 AUG TD.. KUJIRA() 2013 SAUDEL SINLAKU() 2003 OCT JUL 45 SEP NOUL OCT JUL GONI() 2019 SEP NURI(2002) ;< OCT JUN MOLAVE * OCT LINFA SAUDEL(2017) OCT 45 LINFA() 2015 OCT GONI OCT ;< NOV MOLAVE(2018) ETAU OCT NOV NOUL(2011) ETAU() 2021 SEP NOV VAMCO() 2022 ATSANI() 2020 NOV OCT KROVANH(2023) DEC KROVANH DEC VONGFONG(2001) MAY 二零二零年 熱帶氣旋 TROPICAL CYCLONES IN 2020 2 二零二一年七月出版 Published July 2021 香港天文台編製 香港九龍彌敦道134A Prepared by: Hong Kong Observatory, 134A Nathan Road, Kowloon, Hong Kong © 版權所有。未經香港天文台台長同意,不得翻印本刊物任何部分內容。 © Copyright reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced without the permission of the Director of the Hong Kong Observatory. 知識產權公告 Intellectual Property Rights Notice All contents contained in this publication, 本刊物的所有內容,包括但不限於所有 including but not limited to all data, maps, 資料、地圖、文本、圖像、圖畫、圖片、 text, graphics, drawings, diagrams, 照片、影像,以及數據或其他資料的匯編 photographs, videos and compilation of data or other materials (the “Materials”) are (下稱「資料」),均受知識產權保護。資 subject to the intellectual property rights 料的知識產權由香港特別行政區政府 which are either owned by the Government of (下稱「政府」)擁有,或經資料的知識產 the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (the “Government”) or have been licensed to 權擁有人授予政府,為本刊物預期的所 the Government by the intellectual property 有目的而處理該等資料。任何人如欲使 rights’ owner(s) of the Materials to deal with 用資料用作非商業用途,均須遵守《香港 such Materials for all the purposes contemplated in this publication. -

Typhoons and Floods, Manila and the Provinces, and the Marcos Years 台風と水害、マニラと地方〜 マ ルコス政権二〇年の物語

The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus Volume 11 | Issue 43 | Number 3 | Oct 21, 2013 A Tale of Two Decades: Typhoons and Floods, Manila and the Provinces, and the Marcos Years 台風と水害、マニラと地方〜 マ ルコス政権二〇年の物語 James F. Warren The typhoons and floods that occurred in the Marcos years were labelled ‘natural disasters’ Background: Meteorology by the authorities in Manila. But in fact, it would have been more appropriate to label In the second half of the twentieth century, them un-natural, or man-made disasters typhoon-triggered floods affected all sectors of because of the nature of politics in those society in the Philippines, but none more so unsettling years. The typhoons and floods of than the urban poor, particularly theesteros - the 1970s and 1980s, which took a huge toll in dwellers or shanty-town inhabitants, residing in lives and left behind an enormous trail of the low-lying locales of Manila and a number of physical destruction and other impacts after other cities on Luzon and the Visayas. The the waters receded, were caused as much by growing number of post-war urban poor in the interactive nature of politics with the Manila, Cebu City and elsewhere, was largely environment, as by geography and the due to the policy repercussions of rapid typhoons per se, as the principal cause of economic growth and impoverishment under natural calamity. The increasingly variable 1 the military-led Marcos regime. At this time in nature of the weather and climate was a the early 1970s, rural poverty andcatalyst, but not the sole determinant of the environmental devastation increased rapidly, destruction and hidden hazards that could and on a hitherto unknown scale in the linger for years in the aftermath of the Philippines. -

Disaster Preparedness Checklist

DISASTER PREPAREDNESS GO BAG: What to prepare? Emergency Contacts Out of Region Contact THE CHECKLIST Name: _______________________________________ Address: _____________________________________ _____________________________________________ Cell Phone ____________________________________ Home Phone __________________________________ Emergency Kit Work Phone ___________________________________ Local Contact Name: _______________________________________ Address: ______________________________________ _____________________________________________ Cell Phone: ___________________________________ Gears and Tools Home Phone __________________________________ Work Phone: __________________________________ The Philippine Quakes The Philippine Typhoons The Philippine archipelago is located along the Pacific Ring of Fire, the home ...in the next of 90 percent of earthquakes. As a country, Philippines had experienced some Typhoon Yolanda, after sustaining at the speed major tremors and the most recent was the October 15, 2013 in the islands of Bohol, which epicenter was located at the municipality of Sagbayan. of 314 km per hour, accelerated to 378kph making the When disaster happens… 4th strongest typhoon to hit in the country. Among the most destructive earthquakes in the country according to the magnitude of the tremors scaled at Philippine Seismic Intensity standard Will you survive the next 72 hours? 1. Unleashing the windy fury in the islands of Ormoc were: and Leyte on November 15, 1991, Tropical What do you have to sustain in the next three days without an Storm Thelma killed 5,100 people. 1. The 7.3 magnitude that hit the town of Casiguan, Aurora in 1968. The open shop around? tremor was felt almost in the entire Luzon area. Some business towers 2. Typhoon Bopha hit Southern Mindanao on in Manila area collapsed, killing 300 tenants inside the six-story Ruby December 3, 2012, unleashing its strength to the Tower in Binondo. -

Typhoons and Floods, Manila and the Provinces, and the Marcos Years 台風と水害、マニラと地方〜 マ ルコス政権二〇年の物語

Volume 11 | Issue 43 | Number 3 | Article ID 4018 | Oct 21, 2013 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus A Tale of Two Decades: Typhoons and Floods, Manila and the Provinces, and the Marcos Years 台風と水害、マニラと地方〜 マ ルコス政権二〇年の物語 James F. Warren The typhoons and floods that occurred in the Marcos years were labelled ‘natural disasters’ Background: Meteorology by the authorities in Manila. But in fact, it would have been more appropriate to label In the second half of the twentieth century, them un-natural, or man-made disasters typhoon-triggered floods affected all sectors of because of the nature of politics in those society in the Philippines, but none more so unsettling years. The typhoons and floods of than the urban poor, particularly theesteros - the 1970s and 1980s, which took a huge toll in dwellers or shanty-town inhabitants, residing in lives and left behind an enormous trail of the low-lying locales of Manila and a number of physical destruction and other impacts after other cities on Luzon and the Visayas. The the waters receded, were caused as much by growing number of post-war urban poor in the interactive nature of politics with the Manila, Cebu City and elsewhere, was largely environment, as by geography and the due to the policy repercussions of rapid typhoons per se, as the principal cause of economic growth and impoverishment under natural calamity. The increasingly variable 1 the military-led Marcos regime. At this time in nature of the weather and climate was a the early 1970s, rural poverty andcatalyst, but not the sole determinant of the environmental devastation increased rapidly, destruction and hidden hazards that could and on a hitherto unknown scale in the linger for years in the aftermath of the Philippines. -

Development of Inundation Map for Bantayan Island, Cebu Using Delft3d- Flow Storm Surge Simulations of Typhoon Haiyan

Project NOAH Open-File Reports Vol. 3 (2014), pp. 37-44, ISSN 2362 7409 Development of Inundation Map for Bantayan Island, Cebu Using Delft3D- Flow Storm Surge Simulations of Typhoon Haiyan Camille Cuadra, Nophi Ian Biton, Krichi May Cabacaba, Joy Santiago, John Kenneth Suarez, John Phillip Lapidez, Alfredo Mahar Francisco Lagmay, Vicente Malano Abstract: On average, 20 typhoons enter the Philippine Area of Responsibility annually, making it vulnerable to different storm hazards. Apart from the frequency of tropical cyclones, the archipelagic nature of the country makes it particularly prone to storm surges. On 08 November 2013, Haiyan, a Category 5 Typhoon with maximum one- minute sustained wind speed of 315 kph, hit the central region of the Philippines. In its path, the howler devastated Bantayan Island, a popular tourist destination. The island is located north of Cebu City, the second largest metropolis of the Philippines in terms of populace. Having been directly hit by Typhoon Haiyan, Bantayan Island was severely damaged by strong winds and storm surges, with more than 11,000 houses totally destroyed while 5,000 more suffered minor damage. The adverse impacts of possible future storm surge events in the island can only be mitigated if hazard maps that depict inundation of the coastal areas of Bantayan are generated. To create such maps, Delft3D-Flow, a hydrodynamic modelling software was used to simulate storm surges. These simulations were made over a 10-m per pixel resolution IfSAR Digital Elevation Model (DEM) and the General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO) bathymetry. The results of the coastal inundation model for Typhoon Haiyan’s storm surges were validated using data collected from field work and local government reports. -

Significant Data on Major Disasters Worldwide, 1900-Present

DISASTER HISTORY Signi ficant Data on Major Disasters Worldwide, 1900 - Present Prepared for the Office of U.S. Foreign Disaster Assistance Agency for International Developnent Washington, D.C. 20523 Labat-Anderson Incorporated Arlington, Virginia 22201 Under Contract AID/PDC-0000-C-00-8153 INTRODUCTION The OFDA Disaster History provides information on major disasters uhich have occurred around the world since 1900. Informtion is mare complete on events since 1964 - the year the Office of Fore8jn Disaster Assistance was created - and includes details on all disasters to nhich the Office responded with assistance. No records are kept on disasters uhich occurred within the United States and its territories.* All OFDA 'declared' disasters are included - i.e., all those in uhich the Chief of the U.S. Diplmtic Mission in an affected country determined that a disaster exfsted uhich warranted U.S. govermnt response. OFDA is charged with responsibility for coordinating all USG foreign disaster relief. Significant anon-declared' disasters are also included in the History based on the following criteria: o Earthquake and volcano disasters are included if tbe mmber of people killed is at least six, or the total nmber uilled and injured is 25 or more, or at least 1,000 people art affect&, or damage is $1 million or more. o mather disasters except draught (flood, storm, cyclone, typhoon, landslide, heat wave, cold wave, etc.) are included if the drof people killed and injured totals at least 50, or 1,000 or mre are homeless or affected, or damage Is at least S1 mi 1l ion. o Drought disasters are included if the nunber affected is substantial. -

二零一七熱帶氣旋tropical Cyclones in 2017

=> TALIM TRACKS OF TROPICAL CYCLONES IN 2017 <SEP (), ! " Daily Positions at 00 UTC(08 HKT), :; SANVU the number in the symbol represents <SEP the date of the month *+ Intermediate 6-hourly Positions ,')% Super Typhoon NORU ')% *+ Severe Typhoon JUL ]^ BANYAN LAN AUG )% Typhoon OCT '(%& Severe Tropical Storm NALGAE AUG %& Tropical Storm NANMADOL JUL #$ Tropical Depression Z SAOLA( 1722) OCT KULAP JUL HAITANG JUL NORU( 1705) JUL NESAT JUL MERBOK Hong Kong / JUN PAKHAR @Q NALGAE(1711) ,- AUG ? GUCHOL AUG KULAP( 1706) HATO ROKE MAWAR <SEP JUL AUG JUL <SEP T.D. <SEP @Q GUCHOL( 1717) <SEP T.D. ,- MUIFA TALAS \ OCT ? HATO( 1713) APR JUL HAITANG( 1710) :; KHANUN MAWAR( 1716) AUG a JUL ROKE( 1707) SANVU( 1715) XZ[ OCT HAIKUI AUG JUL NANMADOL AUG NOV (1703) DOKSURI JUL <SEP T.D. *+ <SEP BANYAN( 1712) TALAS(1704) \ SONCA( 1708) JUL KHANUN( 1720) AUG SONCA JUL MERBOK (1702) => OCT JUL JUN TALIM( 1718) / <SEP T.D. PAKHAR( 1714) OCT XZ[ AUG NESAT( 1709) T.D. DOKSURI( 1719) a JUL APR <SEP _` HAIKUI( 1724) DAMREY NOV NOV de bc KAI-( TAK 1726) MUIFA (1701) KIROGI DEC APR NOV _` DAMREY( 1723) OCT T.D. APR bc T.D. KIROGI( 1725) T.D. T.D. JAN , ]^ NOV Z , NOV JAN TEMBIN( 1727) LAN( 1721) TEMBIN SAOLA( 1722) DEC OCT DEC OCT T.D. OCT de KAI- TAK DEC 更新記錄 Update Record 更新日期: 二零二零年一月 Revision Date: January 2020 頁 3 目錄 更新 頁 189 表 4.10: 二零一七年熱帶氣旋在香港所造成的損失 更新 頁 217 附件一: 超強颱風天鴿(1713)引致香港直接經濟損失的 新增 估算 Page 4 CONTENTS Update Page 189 TABLE 4.10: DAMAGE CAUSED BY TROPICAL CYCLONES IN Update HONG KONG IN 2017 Page 219 Annex 1: Estimated Direct Economic Losses in Hong Kong Add caused by Super Typhoon Hato (1713) 二零一 七 年 熱帶氣旋 TROPICAL CYCLONES IN 2017 2 二零一九年二月出版 Published February 2019 香港天文台編製 香港九龍彌敦道134A Prepared by: Hong Kong Observatory 134A Nathan Road Kowloon, Hong Kong © 版權所有。未經香港天文台台長同意,不得翻印本刊物任何部分內容。 ©Copyright reserved. -

A Potential Risk Index Dataset for Landfalling Tropical Cyclones in the Chinese Mainland (PRITC Dataset V1.0)

A Potential Risk Index Dataset for Landfalling Tropical Cyclones in the Chinese mainland (PRITC dataset V1.0) Peiyan CHEN1,2,3, Hui YU1.21 , Kevin K. W. Cheung4, Jiajie Xin1, and Yi Lu1,2,3 1Shanghai Typhoon Institute of Chinese Meteorological Administration, Shanghai 200030, China 2Key Laboratory of Numerical Modeling for Tropical Cyclone of Chinese Meteorological Administration, Shanghai 20030, China 3The Joint Laboratory for Typhoon Forecasting Technique Applications between Shanghai Typhoon Institute and Wenzhou Meteorological Bureau, Wenzhou 325027, China 4Climate and Atmospheric Science, NSW Department of Planning Industry and Environment, Sydney, 2000, Australia Submitted to Advances in Atmospheric Sciences in press26 October 2020 *Corresponding author : Hui YU Email: [email protected], Tel: 86-21-54896309. Fax: 86-21-64391966. Address: No. 166 Puxi Road, Shanghai 200030, Chin 1 ABSTRACT A dataset entitled “A potential risk index dataset for landfalling tropical cyclones in the Chinese mainland” (PRITC dataset V1.0) is described in this paper, as are some basic statistical analyses. Chen et al. (2019) proposed estimating the severity of the impacts of TCs that make landfall on the Chinese mainland based on observations from 1401 meteorological stations, including an index combining TC-induced precipitation and wind (IPWT) and further information, such as the corresponding category level (CAT_IPWT), an index of TC-induced wind (IWT), and an index of TC-induced precipitation (IPT). The current version of the dataset includes TCs that made landfall from 1949-2018; the dataset will be extended each year. Long-term trend analyses demonstrated that the severity of the TC impacts on the Chinese mainland increased, as embodied by the annual mean IPWT values, and increases in TC-induced precipitation were the main contributor to this increase. -

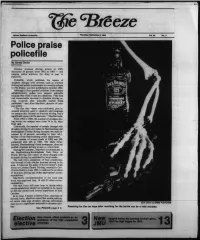

The Breeze, Was First Published in October 1982

James Madison University Thursday, September 6,1864 Vol.62 No. 3 Police praise policefile By Sandy Stone staff writer Campus ' drunken driving arrests at JMU decreased 24 percent from 1982 to 1983 — and campus police attribute the drop in part to policefile. Policefile, which publishes the names of students charged with offenses such as drunken driving and public drunkenness in a weekly column in The Breeze, was first published in October 1982. Although it first sparked criticism from campus administrators, police now support policefile because they think it acts as a deterrent. "The first real measureable decrease in drunken driving ar- rests occurred after policefile started being published," said Alan MacNutt, director of cam- pus police. "The fact that names were published, plus in- creased attention paid to speakers and programs on campus that focused on drunken driving, had a significant impact on the decrease," MacNutt said. From 1982 to 1983, the number of drunken driv- ing arrests on campus went from 74 to 56, Mac- Nutt said. Conversely, the number of people charged with drunken driving by city police in Harrisonburg and Rockingham County during the same two years in- creased by 14 percent, according to Capt. M.L. Stroble of the Harrisonburg police department. The number of arrests made in 1982 was 390, compared with 445 in 1983. The Daily News- Record, Harrisonburg's local newspaper, does not publish drunken driving arrests or convictions. During/the summer, MacNutt recommended to the Hamsonburg-Rockingham Task Force on Drunk Driving that names of those charged with drunken driving be published by local media.