AJTDE Volume 4, Number 4, December 2016 Table of Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Financial Results Results for the Half Year to 30 September 2019 BT Group Plc 31 October 2019

Financial results Results for the half year to 30 September 2019 BT Group plc 31 October 2019 BT Group plc (BT.L) today announced its results for the half year to 30 September 2019. Key strategic developments: • Launched a host of new products for consumer and business segments, including the new Halo converged product plans and BT Mobile 5G • Introduced a range of new service initiatives including bringing the BT brand to the high street in over 600 EE/BT dual- branded stores, and to answer 100% of customer calls in the UK & Ireland from January 2020 • Continued to make progress on the BT modernisation agenda, including delivering over £1.1bn transformation benefits, announcing the first locations in our Better Workplace Programme, and disposal of BT Fleet Solutions • Outlined our Skills for Tomorrow programme to provide digital skills training for 10m UK children, families and businesses Operational: • 5G network live in over 20 cities and large towns; 5G smartphone plans now available on both EE and BT brands • Openreach announced the launch of new FTTP 1Gbps and 550Mbps products. FTTP rollout at c.23k premises passed per week; 4.2m ultrafast (FTTP and Gfast) premises passed to date; currently announced plans to build FTTP in 103 locations • Consumer fixed ARPC £38.5, broadly flat year on year; postpaid mobile ARPC £20.8, down 5.5% year on year due to impact of regulation and continued trend towards SIM-only; RGUs per address up to 2.38 • Postpaid mobile churn remains low at 1.2% in Q2 despite impact of auto switching; fixed churn at -

The Dominance and Monopolies Review, Fifth Edition

Dominance and Monopolies Review Fifth Edition Editors Maurits Dolmans and Henry Mostyn lawreviews the Dominance and Monopolies Review The Dominance and Monopolies Review Reproduced with permission from Law Business Research Ltd. This article was first published in The Dominance and Monopolies Review, - Edition 5 (published in July 2017 – editors Maurits Dolmans and Henry Mostyn) For further information please email [email protected] Dominance and Monopolies Review Fifth Edition Editors Maurits Dolmans and Henry Mostyn lawreviews PUBLISHER Gideon Roberton SENIOR BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT MANAGER Nick Barette BUSINESS DEVELOPMENT MANAGERS Thomas Lee, Joel Woods ACCOUNT MANAGERS Pere Aspinall, Sophie Emberson, Laura Lynas, Jack Bagnall MARKETING AND READERSHIP COORDINATOR Rebecca Mogridge RESEARCHER Arthur Hunter EDITORIAL COORDINATOR Gavin Jordan HEAD OF PRODUCTION Adam Myers PRODUCTION EDITOR Martin Roach SUBEDITOR Janina Godowska CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER Paul Howarth Published in the United Kingdom by Law Business Research Ltd, London 87 Lancaster Road, London, W11 1QQ, UK © 2017 Law Business Research Ltd www.TheLawReviews.co.uk No photocopying: copyright licences do not apply. The information provided in this publication is general and may not apply in a specific situation, nor does it necessarily represent the views of authors’ firms or their clients. Legal advice should always be sought before taking any legal action based on the information provided. The publishers accept no responsibility for any acts or omissions contained -

Comodo Threat Intelligence

Comodo Threat Intelligence Lab SPECIAL REPORT: AUGUST 2017 – IKARUSdilapidated Locky Part II: 2nd Wave of Ransomware Attacks Uses Your Scanner/Printer, Post Office Billing Inquiry THREAT RESEARCH LABS Locky Ransomware August 2017 Special Report Part II A second wave of new but related IKARUSdilapidated Locky ransomware attacks has occurred, building on the attacks discovered by the Comodo Threat Intelligence Lab (part of Comodo Threat Research Labs) earlier in the month of August 2017. This late August campaign also uses a botnet of “zombie computers” to coordinate a phishing attack which sends emails appearing to be from your organization’s scanner/printer (or other legitimate source) and ultimately encrypts the victims’ computers and demands a bitcoin ransom. SPECIAL REPORT 2 THREAT RESEARCH LABS The larger of the two attacks in this wave presents as a scanned image emailed to you from your organization’s scanner/printer. As many employees today scan original documents at the company scanner/printer and email them to themselves and others, this malware-laden email will look very innocent. The sophistication here includes even matching the scanner/printer model number to make it look more common as the Sharp MX2600N is one of the most popular models of business scanner/printers in the market. This second wave August 2017 phishing campaign carrying IKARUSdilapidated Locky ransomware is, in fact, two different campaigns launched 3 days apart. The first (featuring the subject “Scanned image from MX-2600N”) was discovered by the Lab to have commenced primarily over 17 hours on August 18th and the second (a French language email purportedly from the French post office featuring a subject including “FACTURE”) was executed over a 15-hour period on August 21st, 2017. -

British Telecommunications Plc Annual Report

wholly-owned subsidiary of BT Group plc, British Telecommunications plc meets the conditions set forth in General set the conditions plc meets Telecommunications plc, British Group subsidiary wholly-owned of BT a As Form 20-F with filing this 20-F and is therefore reports on Form 10-K as applied to of Form Instruction (I) (1)(a) and (b) format. disclosure the reduced 2018 Form 20-F Form Report & Report Annual BRITISH TELECOMMUNICATIONS plc BRITISH TELECOMMUNICATIONS BRITISH TELECOMMUNICATIONS plc 2018 THE StratEGIC REPOrt GOVERNANCE FINANCIAL statEMENts ADDITIONAL INFORMatION Contents The Strategic Report Our strategy Our strategy in a nutshell How we’re doing – Delivering great customer experience 3 – Investing for growth 4 – Transforming our costs 5 Key performance indicators 6 Our non-financial performance 8 Our evolving strategy 10 Our business model Our business model 12 What we do 14 Our resources and culture Financial strength 16 Our networks and physical assets 16 Properties 17 Research and development 17 Brand and reputation 19 Our culture / The BT Way 20 Respecting human rights 21 Our stakeholders Our people 22 Customers 25 Communities and society 25 Lenders 26 Pension schemes 26 Suppliers 27 HM Government 27 Regulators 28 The environment 31 Our risks Our approach to risk management 33 Our principal risks and uncertainties 34 Operating review BT Consumer 48 EE 55 Business and Public Sector 59 Global Services 64 Wholesale and Ventures 69 Openreach 73 Technology, Service and Operations 79 Group performance Group performance 82 Governance 89 Financial statements 95 Additional information 208 Overview British Telecommunications plc (‘the group’ or ‘the company’ ) is the principal operating subsidiary of BT Group plc. -

BT Group Plc Results Release Q4 2020/21

Financial results Results for the full year to 31 March 2021 BT Group plc 13 May 2021 Philip Jansen, Chief Executive, commenting on the results, said “BT comes out of this challenging year as a stronger business with an even greater sense of purpose. Our fantastic colleagues have shown the true colours of BT – delivering resilient connectivity, supporting families and businesses and helping to underpin the heroism of the NHS. A number of uncertainties have now been removed. The Wholesale Fixed Telecoms Market Review, 5G spectrum auction and the Government's tax super-deduction give us the green light to build the UK’s next generation digital infrastructure even faster; today we are increasing and accelerating our FTTP target from 20m to 25m homes and businesses by December 2026 to deliver further value to our shareholders and support the Government’s full fibre ambitions. The conclusion of our triennial pension valuation today provides further clarity for shareholders. After a number of years of tough work, and as we look to build back better from the pandemic, we’re now pivoting to consistent and predictable growth. We are building a better BT for our customers, for the country, for our shareholders and for those who work for this great company – now and in the future.” BT Group plc (BT.L) today announced its results for the full year to 31 March 2021. Key strategic developments: • Ofcom's WFTMR1, outcome of recent spectrum auction and Government’s tax super-deduction allows us to increase and accelerate our FTTP build from 20m to 25m premises by December 2026; BT to explore potential joint venture for additional 5m build - see separate press release • Agreed triennial pension deficit of £7.98bn and deficit recovery plan comprising: asset-backed funding over 13 years (£180m p.a.) secured against the EE business; and further payments over 10 years (£900m p.a. -

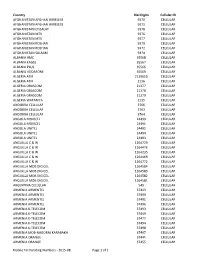

Mobile Terminating Numbers

Country Dial Digits Cellular ID AFGHANISTAN AFGHAN WIRELESS 9370 CELLULAR AFGHANISTAN AFGHAN WIRELESS 9371 CELLULAR AFGHANISTAN ETISALAT 9378 CELLULAR AFGHANISTAN MTN 9376 CELLULAR AFGHANISTAN MTN 9377 CELLULAR AFGHANISTAN ROSHAN 9379 CELLULAR AFGHANISTAN ROSHAN 9372 CELLULAR AFGHANISTAN SALAAM 9374 CELLULAR ALBANIA AMC 35568 CELLULAR ALBANIA EAGLE 35567 CELLULAR ALBANIA PLUS 35566 CELLULAR ALBANIA VODAFONE 35569 CELLULAR ALGERIA ATM 2139619 CELLULAR ALGERIA ATM 2136 CELLULAR ALGERIA ORASCOM 21377 CELLULAR ALGERIA ORASCOM 21378 CELLULAR ALGERIA ORASCOM 21379 CELLULAR ALGERIA WATANIYA 2135 CELLULAR ANDORRA CELLULAR 3766 CELLULAR ANDORRA CELLULAR 3763 CELLULAR ANDORRA CELLULAR 3764 CELLULAR ANGOLA MOVICEL 24499 CELLULAR ANGOLA MOVICEL 24491 CELLULAR ANGOLA UNITEL 24492 CELLULAR ANGOLA UNITEL 24494 CELLULAR ANGOLA UNITEL 24493 CELLULAR ANGUILLA C & W 1264729 CELLULAR ANGUILLA C & W 1264476 CELLULAR ANGUILLA C & W 1264235 CELLULAR ANGUILLA C & W 1264469 CELLULAR ANGUILLA C & W 1264772 CELLULAR ANGUILLA MOB DIGICEL 1264584 CELLULAR ANGUILLA MOB DIGICEL 1264583 CELLULAR ANGUILLA MOB DIGICEL 1264582 CELLULAR ANGUILLA MOB DIGICEL 1264581 CELLULAR ARGENTINA CELLULAR 549 CELLULAR ARMENIA ARMENTEL 37443 CELLULAR ARMENIA ARMENTEL 37499 CELLULAR ARMENIA ARMENTEL 37491 CELLULAR ARMENIA ARMENTEL 37496 CELLULAR ARMENIA K-TELECOM 37493 CELLULAR ARMENIA K-TELECOM 37449 CELLULAR ARMENIA K-TELECOM 37477 CELLULAR ARMENIA K-TELECOM 37494 CELLULAR ARMENIA K-TELECOM 37498 CELLULAR ARMENIA MOB-NAGORNI KARABAKH 37497 CELLULAR ARMENIA ORANGE 37441 CELLULAR ARMENIA -

BT Group Plc Annual Report 2020 BT Group Plc Annual Report 2020 Strategic Report 1

BT Group plc Group BT Annual Report 2020 Beyond Limits BT Group plc Annual Report 2020 BT Group plc Annual Report 2020 Strategic report 1 New BT Halo. ... of new products and services Contents Combining the We launched BT Halo, We’re best of 4G, 5G our best ever converged Strategic report connectivity package. and fibre. ... of flexible TV A message from our Chairman 2 A message from our Chief Executive 4 packages About BT 6 investing Our range of new flexible TV Executive Committee 8 packages aims to disrupt the Customers and markets 10 UK’s pay TV market and keep Regulatory update 12 pace with the rising tide of in the streamers. Our business model 14 Our strategy 16 Strategic progress 18 ... of next generation Our stakeholders 24 future... fibre broadband Culture and colleagues 30 We expect to invest around Introducing the Colleague Board 32 £12bn to connect 20m Section 172 statement 34 premises by mid-to-late-20s Non-financial information statement 35 if the conditions are right. Digital impact and sustainability 36 Our key performance indicators 40 Our performance as a sustainable and responsible business 42 ... of our Group performance 43 A letter from the Chair of Openreach 51 best-in-class How we manage risk 52 network ... to keep us all Our principal risks and uncertainties 53 5G makes a measurable connected Viability statement 64 difference to everyday During the pandemic, experiences and opens we’re helping those who up even more exciting need us the most. Corporate governance report 65 new experiences. Financial statements 117 .. -

James Christian, Et Al. V. BT Group Plc, Et Al. 17-CV-00497-Amended

Case 2:17-cv-00497-KM-JBC Document 26 Filed 11/21/17 Page 1 of 74 PageID: 498 James E. Cecchi CARELLA, BYRNE, CECCHI, OLSTEIN, BRODY & AGNELLO, P.C. 5 Becker Farm Road Roseland, NJ 07068 (973) 994-1700 Liaison Counsel for Plaintiffs Samuel H. Rudman David A. Rosenfeld Alan I. Ellman ROBBINS GELLER RUDMAN & DOWD LLP 58 South Service Road, Suite 200 Melville, NY 11747 (631) 367-7100 Lead Counsel for Plaintiffs UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY JAMES CHRISTIAN, Individually and on ) No. 2:17-cv-00497-KM-JBC Behalf of All Others Similarly Situated, ) ) CLASS ACTION Plaintiff, ) ) vs. ) AMENDED COMPLAINT ) FOR VIOLATIONS OF THE BT GROUP PLC, IAN LIVINGSTON, ) FEDERAL SECURITIES LAWS GAVIN E. PATTERSON, TONY ) CHANMUGAM, and LUIS ALVAREZ, ) ) Defendants. ) DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL Case 2:17-cv-00497-KM-JBC Document 26 Filed 11/21/17 Page 2 of 74 PageID: 499 Lead Plaintiff PAMCAH-UA Local 675 Pension Fund and Plaintiff Clayton Hollister (together, “Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and on behalf of all others similarly situated, allege the following based upon personal knowledge as to themselves and their own acts, and upon information and belief as to all other matters based on the investigation conducted by their attorneys, which included, among other things, the review and analysis of: (i) U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) filings by BT Group plc (“BT Group” or the “Company”); (ii) transcripts of earnings calls with BT Group senior management; (iii) press releases, investor presentations, and other information issued or disseminated by the defendants; (iv) news articles and media coverage of the events giving rise to this action; and (v) research and reports by securities and financial analysts. -

List of International Signalling Point Codes (ISPC)

国际电联《操作公报》附件 第1199 – 1.VII.2020期 国际电信联盟 TSB 国际电信联盟 电信标准化局 _______________________________________________________________ 国际信令点代码(ISPC)列表(根据ITU-T Q.708建议书(03/1999))(截至2020年7月1 日) (截至2020年7月1日) _______________________________________________________________ 2020,日内瓦 List of International Signalling Point Codes (ISPC) Note from TSB 1. This List of International Signalling Point Codes (ISPC) replaces the previous one published as Annex to the ITU Operational Bulletin No. 1109 of 1.X.2016. Since then, a number of notifications have been received at TSB and they have been published separately in various issues of the ITU Operational Bulletin. The present list recapitulates all the different amendments that have been published up to ITU Operational Bulletin No. 1199 of 1.VII.2020. 2. Recommendation ITU-T Q.708 states that the assignment of signalling area/network codes (SANC) is to be administered by TSB. Each country will then be responsible for the assignment of international signalling point codes (ISPC) that will then be notified to TSB. 3. The numbering plan of Recommendation ITU-T Q.708 contains 2 048 SANCs providing for 16 384 international signalling points. From these, currently 1 536 SANCs are available for assignment allowing for 12 288 international points. At present 1 055 SANCs are assigned; the reported utilization is 6 255 international signalling points. 4. In order to keep the list up to date, administrations are, therefore, requested to notify TSB, by using the notification form attached, as soon as an ISPC assignment or withdrawal is made, www.itu.int/en/ITU-T/inr/forms/Pages/ispc.aspx . 5. This List will be updated by numbered series of amendments published in the ITU Operational Bulletin. -

Corporate Governance Case Studies Volume 7

CORPORATE GOVERNANCE CASE STUDIES VOLUME SEVEN Edited by Mak Yuen Teen Corporate Governance Case Studies Volume seven Mak Yuen Teen, PhD, FCPA (Aust.) Editor First published October 2018 Copyright ©2018 Mak Yuen Teen and CPA Australia All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher, except for inclusion of brief quotations in a review. The views expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of, and should not be attributed to, CPA Australia Ltd. Please contact CPA Australia or Professor Mak Yuen Teen for permission of use of any case studies in this publication. Corporate Governance Case Studies Volume Seven Editor : Mak Yuen Teen, PhD, FCPA (Aust.) Editor’s email : [email protected] Published by : CPA Australia Ltd 1 Raffles Place #31-01 One Raffles Place Singapore 048616 Website : cpaaustralia.com.au Email : [email protected] ISBN : 978-981-11-8936-4 II Contents Foreword Preface Singapore Cases Is Datapulse Flatlining? ................................................................................................. 1 Fat Leonard: The Elephant In The U.S. Navy’s Room .................................................. 42 A Good Deal? Privatisation Of Global Logistic Properties ........................................... 57 The Diagnosis Of Healthway ...................................................................................... -

James Christian, Et Al. V. BT Group Plc, Et Al. 17-CV-00497-Second

Case 2:17-cv-00497-KM-JBC Document 47 Filed 10/01/18 Page 1 of 95 PageID: 937 James E. Cecchi CARELLA, BYRNE, CECCHI, OLSTEIN, BRODY & AGNELLO, P.C. 5 Becker Farm Road Roseland, NJ 07068 (973) 994-1700 Liaison Counsel for Plaintiffs and the Putative Class Samuel H. Rudman David A. Rosenfeld Alan I. Ellman ROBBINS GELLER RUDMAN & DOWD LLP 58 South Service Road, Suite 200 Melville, NY 11747 (631) 367-7100 Lead Counsel for Plaintiffs and the Putative Class [Additional counsel appear on signature page.] UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT DISTRICT OF NEW JERSEY JAMES CHRISTIAN, Individually and on ) No. 2:17-cv-00497-KM-JBC Behalf of All Others Similarly Situated, ) ) CLASS ACTION Plaintiff, ) ) vs. ) SECOND AMENDED COMPLAINT ) FOR VIOLATIONS OF THE BT GROUP PLC, IAN LIVINGSTON, ) FEDERAL SECURITIES LAWS GAVIN E. PATTERSON, TONY ) CHANMUGAM and LUIS ALVAREZ, ) Defendants. ) ) DEMAND FOR JURY TRIAL Case 2:17-cv-00497-KM-JBC Document 47 Filed 10/01/18 Page 2 of 95 PageID: 938 Lead Plaintiff PAMCAH-UA Local 675 Pension Fund and Plaintiff Clayton Hollister (together, “Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and on behalf of all others similarly situated, allege the following based upon personal knowledge as to themselves and their own acts, and upon information and belief as to all other matters based on the investigation conducted by their attorneys, which included, among other things, the review and analysis of: (i) U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) filings by BT Group plc (“BT Group” or the “Company”); (ii) transcripts of earnings calls with BT Group senior management; (iii) press releases, investor presentations, and other information issued or disseminated by the defendants; (iv) news articles and media coverage of the events giving rise to this action; and (v) research and reports by securities and financial analysts. -

Italtel Corporate Presentation

Italtel Corporate Presentation March 2018 Mission WE POWER SEAMLESS COMMUNICATION OF PEOPLE AND OBJECTS, TECHNOLOGIES AND NETWORKS 2 December 14, 2017: a new player is born... Italtel and Exprivia, a new Italian ICT group that intends to be a leader in the digital transformation space through the development of innovative solutions and services. 3 Italtel Evolutionary Focus: Market Trends Markets Vertical Utilities PA Banks Telco Industry 4.0 Healthcare Smart Grids Smart Cities FinTech High Definition Video Mobile & Fixed (4K) & Market Trends Digital Cloud Computing Apps & Virtualization (NFV & SDN) Enablers Big Data Cyber Security 200 B$ / 10% growth in 2015 – 2019 for Italtel Reference Market The Digital Revolution…surfing the Digitization Wave 4 Italtel Product Catalogue Management i-DCP i-NES i-DEVMAN i-NEM i-QAC Proprietary High Tools and applications to Multivendor & multi Italtel Neutral Element Italtel Quality Assurance Performing ETL engine for support IP Network technology CPE Manager Manager Center multi domain networks Operations NGN – IMS/VoLTE SDN Monitoring & Automation Contextual Communication Based on Embrace WebRTC AS IMS/NGN (Core/Border) Enterprise SDN Driver AS: MMTEL, SCC-AS, IM-SSF, etc. Internet of Things The Data Suite HSS, USPDB Italtel IoT Platform for data gathering & processing Routing & Border Layer Policy Server NetMatch-S SBC UNI/NNI P-CSCF E-SBC ATCF/ATGW WebRTC GW E-CSCF / EATF NFV MANO NetMatch-M NGN/IMS Italtel VNF Manager Media GW/Signaling GW 5 Worldwide presence and highlights ARGENTINA ITALY BRAZIL BELGIUM COLOMBIAa FRANCE ECUADOR GERMANY PERU POLAND SPAIN USA UK 100+ active customers worldwide 4 of top 8 Worldwide Communication Service Provider groups More than 1300 people worldwide, 1100 of Most of European incumbent Communication Service whom in Italy and about 200 abroad.