Pope Francis's Strong Thought

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPE FRANCIS AS a GLOBAL ACTOR Where Politics and Theology Meet

POPE FRANCIS AS A GLOBAL ACTOR Where Politics and Theology Meet EDITED BY ALYNNA J. LYON, CHRISTINE A. GUSTAFSON, AND PAUL CHRISTOPHER MANUEL Palgrave Studies in Religion, Politics, and Policy Series editor Mark J. Rozell Schar School of Policy and Government George Mason University Arlington, VA, USA A generation ago, many social scientists regarded religion as an anachronism, whose social, economic, and political importance would inevitably wane and disap- pear in the face of the inexorable forces of modernity. Of course, nothing of the sort has occurred; indeed, the public role of religion is resurgent in US domestic politics, in other nations, and in the international arena. Today, religion is widely acknowledged to be a key variable in candidate nominations, platforms, and elections; it is recognized as a major influence on domestic and foreign policies. National religious movements as diverse as the Christian Right in the United States and the Taliban in Afghanistan are important factors in the internal politics of par- ticular nations. Moreover, such transnational religious actors as Al-Qaida, Falun Gong, and the Vatican have had important effects on the politics and policies of nations around the world. Palgrave Studies in Religion, Politics, and Policy serves a growing niche in the discipline of political science. This subfield has proliferated rapidly during the past two decades, and has generated an enormous amount of scholarly studies and journalistic coverage. Five years ago, the journal Politics and Religion was created; in addition, works relating to religion and politics have been the subject of many articles in more general academic journals. -

40"" Anniversary of Del Verbum International Congress "Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church" CATHOLIC BIBLICAL FEDERATION 4T

VERBUM ic Biblical Federation I I I I I } i V \ 40"" Anniversary of Del Verbum International Congress "Sacred Scripture in the Life of the Church" CATHOLIC BIBLICAL FEDERATION 4t BULLETIN DEI VERBUM is a quarterly publica tion in English, French, German and Spanish. Editors Alexander M. Schweitzer Glaudio EttI Assistant to the editors Dorothea Knabe Production and layout bm-projekte, 70771 Leinf.-Echterdingen A subscription for one year consists of four issues beginning the quarter payment is Dei Verbum Congress 2005 received. Please indicate in which language you wish to receive the BULLETIN DEI VERBUM. Summary Subscription rates ■ Ordinary subscription: US$ 201 €20 ■ Supporting subscription: US$ 34 / € 34 Audience Granted by Pope Benedict XVI « Third World countries: US$ 14 / € 14 ■ Students: US$ 14/€ 14 Message of the Holy Father Air mail delivery: US$ 7 / € 7 extra In order to cover production costs we recom mend a supporting subscription. For mem Solemn Opening bers of the Catholic Biblical Federation the The Word of God In the Life of the Church subscription fee is included in the annual membership fee. Greeting Address by the CBF President Msgr. Vincenzo Paglia 6 Banking details General Secretariat "Ut Dei Verbum currat" (Address as indicated below) LIGA Bank, Stuttgart Opening Address of the Exhibition by the CBF General Secretary A l e x a n d e r M . S c h w e i t z e r 1 1 Account No. 64 59 820 IBAN-No. DE 28 7509 0300 0006 4598 20 BIO Code GENODEF1M05 Or per check to the General Secretariat. -

Enrico Impalà When Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini Passed Away in 2012

Book Reviews 365 Enrico Impalà Vita del Cardinal Martini. Il Bosco e il Mendicante. Rome: San Paolo Edizioni, 2014. Pp. 261. Pb, 15.00 Euros. When Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini passed away in 2012, a storm of (mostly Italian) newspaper articles appeared in honor of the archbishop, who had been both a scholar and a socially-conscious man of God. In him, it seemed that the Ambrosian tradition had found a great exponent, in the tradition of Carlo Borromeo in the sixteenth century. Unfortunately, the discussion in the media focused on only two aspects of Martini’s wide interests: namely, the dialogue between faith and atheism, and his societal involvement. Above all, this was due to his prolific journalistic activity, as a columnist for a national newspaper in Italy. With few exceptions, Martini’s portrait, as rendered by these journalists, hardly resembled a Jesuit. Furthermore, the political categories so often used to describe his position with the college of cardinals impeded a nuanced understanding of his spiritual path. Enrico Impalà’s Il Bosco e il Mendicante [The Woods and the Beggar] aims to fill this gap. Among the many biographies that appeared after the cardinal’s death, this well-written, anecdotal account deserves special attention, because its author was one of Martini’s colleagues during his tenure in Milan. The book’s curious title echoes a Hindu proverb that Martini was fond of quoting during his last years of pastoral work in Milan, to the effect that life has four stages: the first, when one learns from others; the second, when one teaches others; the third, when the time comes to enter the woods and meditate; and the last, when one becomes a beggar, since one requires help from everyone, for everything. -

Edited by Conor Hill, Kent Lasnoski, Matthew Sherman, John Sikorski and Matthew Whelan

VOLUME 6, NUMBER 2 JUNE 2017 NEW WINE, NEW WINESKINS: PERSPECTIVES OF YOUNG MORAL THEOLOGIANS Edited by Conor Hill, Kent Lasnoski, Matthew Sherman, John Sikorski and Matthew Whelan Journal of Moral Theology is published semiannually, with issues in January and June. Our mission is to publish scholarly articles in the field of Catholic moral theology, as well as theological treatments of related topics in philosophy, economics, political philosophy, and psychology. Articles published in the Journal of Moral Theology undergo at least two double blind peer reviews. Authors are asked to submit articles electronically to [email protected]. Submissions should be prepared for blind review. Microsoft Word format preferred. The editors assume that submissions are not being simultaneously considered for publication in another venue. Journal of Moral Theology is indexed in the ATLA Catholic Periodical and Literature Index® (CPLI®), a product of the American Theological Library Association. Email: [email protected], www: http://www.atla.com. ISSN 2166-2851 (print) ISSN 2166-2118 (online) Journal of Moral Theology is published by Mount St. Mary’s University, 16300 Old Emmitsburg Road, Emmitsburg, MD 21727. Copyright© 2017 individual authors and Mount St. Mary’s University. All rights reserved. EDITOR EMERITUS AND UNIVERSITY LIAISON David M. McCarthy, Mount St. Mary’s University EDITOR Jason King, Saint Vincent College ASSOCIATE EDITOR William J. Collinge, Mount St. Mary’s University MANAGING EDITOR Kathy Criasia, Mount St. Mary’s University EDITORIAL BOARD Melanie Barrett, University of St. Mary of the Lake/Mundelein Seminary Jana M. Bennett, University of Dayton Mara Brecht, St. Norbert College Jim Caccamo, St. -

Archivum Historicum Societatis Iesu

ARCHIVUM HISTORICUM SOCIETATIS IESU VOL. LXXXII, FASC. 164 2013/II Articles Charles Libois S.J., L’École des Jésuites au Caire dans l’Ancienne Compagnie. 355 Leonardo Cohen, El padre Pedro Páez frente a la interpretación bíblica etíope. La controversia sobre “cómo llenar una 397 brecha mítica”. Claudia von Collani, Astronomy versus Astrology. Johann Adam Schall von Bell and his “superstitious” Chinese Calendar. 421 Andrea Mariani, Mobilità e formazione dei Gesuiti della Confederazione polacco-lituana. Analisi statistico- prosopografica del personale dei collegi di Nieśwież e Słuck (1724-1773). 459 Francisco Malta Romeiras, The emergence of molecular genetics in Portugal: the enterprise of Luís Archer SJ. 501 Bibliography (Paul Begheyn S.J.) 513 Book Reviews Charlotte de Castelnau-L’Estoile et alia, Missions d’évangélisation et circulation des savoirs XVIe- XVIIIe siècle (Luce Giard) 633; Pedro de Valencia, Obras completas. VI. Escritos varios (Doris Moreno) 642; Wolfgang Müller (Bearb.), Die datierten Handschriften der Universitätsbibliothek München. Textband und Tafelband (Rudolf Gamper) 647; Ursula Paintner, Des Papsts neue Creatur‘. Antijesuitische Publizistik im Deutschsprachigen Raum (1555-1618) (Fabian Fechner) 652; Anthony E. Clark, China’s Saints. Catholic Martyrdom during the Qing (1644-1911) (Marc Lindeijer S.J.) 654; Thomas M. McCoog, “And touching our Society”: Fashioning Jesuit Identity in Elizabethan England (Michael Questier) 656; Festo Mkenda, Mission for Everyone: A Story of the Jesuits in East Africa (1555-2012) (Brendan Carmody S.J.) 659; Franz Brendle, Der Erzkanzler im Religionskrieg. Kurfürst Anselm Casimir von Mainz, die geistlichen Fürsten und das Reich 1629 bis 1647 (Frank Sobiec) 661; Robert E. Scully, Into the Lion’s Den. -

Piemme – Religious RL – Frankfurt Fall 2019

RELIGIOUS BOOKS RIGHTS LIST FALL 2019 CONTENTS 03 THE WORDS OF CHRISTMAS 11 JOURNEYING Pope Francis Andrea Tornielli 04 HAPPY NEW YEAR 12 LEARNING TO BELIEVE The joy of Christmas that animates us Carlo Maria Martini Pope Francis 13 LEARNING TO SMILE 05 PRAYER THE JOY OF THE GOSPEL Breathing life, daily Carlo Maria Martini Pope Francis 14 ON THE BORDER 06 INSIDE JOY AGAINST FEAR AND INDIFFERENCE The reasons for our hope Nunzio Galatino Pope Francis 15 INHABITING WORDS 07 HAPPINESS IN THIS LIFE A GRAMMAR OF THE HEART A passionate meditation on our life’s ultimate meaning Nunzio Galatino Foreword by Pope Francis Pope Francis 16 HATE THY NEIGHBOR WHY WE HAVE FORGOTTEN 08 GOD IS YOUNG Brotherly Love A conversation with Thomas Leoncini Matteo Maria Zuppi Pope Francis 17 LIVING FOREVER 09 THE NAME OF GOD IS MERCY Vincenzo Paglia A conversation with Andrea Tornielli Pope Francis 18 THE DAY OF JUDGMENT Andrea Tornielli and Gianni Valente 10 FRIEND GOD The book that protects you from loneliness 19 POSSESSED Pope Francis Massimo Centini 20 LIFE AS AN EXORCIST The most disturbing cases of possession and deliverance Father Cesare Turqui with Chiara Santomiero 21 ONLY THE GOSPEL IS REVOLUTIONARY A conversation with Antonio Carriero Óscar Maradiaga RELIGIOUS THE WORDS OF CHRISTMAS POPE FRANCIS Imprint: Piemme Pages: 192 Publication: October 2019 A path to Christmas through words helping us to rediscover the true meaning of the most joyous festivity of the year. Advent is a path inviting us to look beyond our set and tired ways and open our minds and hearts to Jesus. -

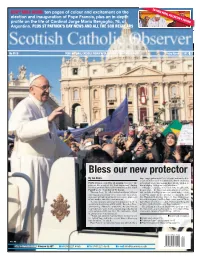

Bless Our New Protector

28-PAGE PAPAL COLLECTOR’S EDITION DON’T MISS INSIDE ten pages of colour and excitement on the election and inauguration of Pope Francis, plus an in-depth profile on the life of Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, 76, of Argentina. PLUS ST PATRICK’S DAY NEWS AND ALL THE SCO REGULARS No 5510 YOUR NATIONAL CATHOLIC NEWSPAPER SUPPORTS THE YEAR OF FAITH Friday March 22 2013 | £1 Bless our new protector By Ian Dunn huge congregation in St Peter’s Square and watched by a vast television audience around the world, including POPE Francis called for all mankind to serve ‘the in Scotland where our bishops have already written to poorest, the weakest, the least important,’ during him pledging ‘loving and loyal obedience.’ the inauguration Mass of his ministry as the 266th Although according to Church law, he officially Pontiff on the feast day of St Joseph. became Pope—the first Jesuit and Latin American Pon- The new Pope, 76, called in his homily for ‘all men tiff, and the first Pope from a religious order in 150 and women of goodwill’ to be ‘protectors of creation, years—the minute he accepted his election in the Sis- protectors of God’s plan inscribed in nature, protectors tine Chapel on Wednesday March 13, Pope Francis was of one another and of the environment.’ formally inaugurated as Holy Father at the start of Tues- “Let us not allow omens of destruction and death to day’s Mass, when he received the Fisherman’s Ring and accompany the advance of this world,” he said on Tues- pallium, symbolising his new Papal authority. -

Faith in a Postmodern World Carlo Maria Martini

May 12, 2008AmericaTHE NATIONAL CATHOLIC WEE LY $2.75 Faith in a Postmodern World Carlo Maria Martini Commentary on the Papal Visit Y MOVE TO BROOKLYN from carrying a stroller, with a child in tow or Manhattan last year seemed in her arms. America daunting, and I am still pro- A sadder mood arises at the sight of Published by Jesuits of the United States cessing that change to a dif- homeless people, for whom the subway Mferent world. The link in both cases, cars and the benches on the platforms Editor in Chief though, has been a Jesuit parish. In often serve as shelter. On one occasion, Manhattan it was Nativity, now closing an elderly woman boarded a Brooklyn- Drew Christiansen, S.J. because of gentrification that has driven bound train in the late afternoon and, Acting Publisher out many parishioners. In Brooklyn it is seating herself opposite me, carefully the parish of St. Ignatius. Both are small, arranged the huge plastic bags with her James Martin, S.J. with a mix of nationalities among the possessions at her feet. To some, her Managing Editor parishioners. Although my work at world may have seemed chaotic, but at Robert C. Collins, S.J. America continues full time, I have always least for a few moments, she had instilled loved the rhythms of parish life, saying into it a sense of order. Business Manager Mass and getting to know parishioners in On one of the inbound train platforms Lisa Pope all their diversity of age, background and every weekday morning, I pass an elderly interests. -

Astrobiology and Humanism

Astrobiology and Humanism Astrobiology and Humanism: Conversations on Science, Philosophy and Theology By Julian Chela-Flores Astrobiology and Humanism: Conversations on Science, Philosophy and Theology By Julian Chela-Flores This book first published 2019 Cambridge Scholars Publishing Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2019 by Julian Chela-Flores All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-3436-7 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-3436-0 To: Sarah Catherine Mary Dowling Philosophy, as I shall understand the word, is something intermediate between theology and science. Like theology, it consists of speculations on matters as to which definite knowledge has, so far, been unascertainable; but like science it appeals to human reason rather than authority, whether that of tradition or that of revelation…But between theology and science there is a No Man’s Land, exposed to attack from both sides; this No Man’s Land is philosophy. —Bertrand Russell: “History of Western Philosophy and its Connection with Political and Social Circumstances from the Earliest Times to the Present Day”. 2nd Edition. George Allen & Unwin, London (1991), p. 13. Contrary to the popular but inaccurate picture of science and theology being at loggerheads with each other, the fact of the matter is that there is a lively debate between the two disciplines, and many of the contributors to that debate are themselves scientists with a personal commitment to religion and a serious concern with theology. -

![Mbiun [Library Ebook] Pope Francis: Conversations with Jorge Bergoglio: His Life in His Own Words Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4211/mbiun-library-ebook-pope-francis-conversations-with-jorge-bergoglio-his-life-in-his-own-words-online-2494211.webp)

Mbiun [Library Ebook] Pope Francis: Conversations with Jorge Bergoglio: His Life in His Own Words Online

MbiuN [Library ebook] Pope Francis: Conversations with Jorge Bergoglio: His Life in His Own Words Online [MbiuN.ebook] Pope Francis: Conversations with Jorge Bergoglio: His Life in His Own Words Pdf Free Francesca Ambrogetti, Sergio Rubin *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #450867 in Books Sergio Rubin Francesca Ambrogetti 2014-10-28 2014-10-28Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.22 x .66 x 5.44l, 1.00 #File Name: 0451469410304 pagesPope Francis Conversations with Jorge Bergoglio | File size: 53.Mb Francesca Ambrogetti, Sergio Rubin : Pope Francis: Conversations with Jorge Bergoglio: His Life in His Own Words before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Pope Francis: Conversations with Jorge Bergoglio: His Life in His Own Words: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. MUSICAL "TRIVIA"By VincentWe read Pope Francis' most admire musical composition Beethoven’s Leonore Overture No. 3, in the version by Wilhelm Furtwängler, who, as he sees it, is the finest conductor of certain of Beethoven’s symphonies and the works of Wagner. •••Yet, he would want to remember:I Corinthians 2:9 (...) "nor ear heard, nor the heart of man conceived, what God has prepared for those who love him."0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. ExcellentBy Les GapayExcellent book. Great insight into the now pope.1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. great background on how the Pope thinksBy DavidThis book gives much greater insight into who Pope Francis is. -

The Holy See

The Holy See MESSAGE OF JOHN PAUL II TO CARDINAL CARLO MARIA MARTINI FOR THE 750TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE MARTYRDOM OF ST PETER MARTYR To my Venerable Brother Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini Archbishop of Milan 1. I was delighted to learn that the Ambrosian Church and the Order of Friars Preachers are preparing to celebrate the 750th anniversary of the martyrdom of St Peter Martyr, a Dominican religious who, with his colleague Fra Dominic, was killed for the faith on 6 April 1252, the Saturday after Easter, near Seveso, while travelling to Milan to take up a new mission of evangelization and defence of the Catholic faith. The anniversary, which this year too coincides with the Saturday after Easter, is an incentive to look with admiration and gratitude at the figure and work of this saint who, seized by Christ, fulfilled in his life the words of the Apostle Paul: "Woe to me if I do not preach the Gospel!" (I Cor 9,16), and, with his martyrdom, obtained the grace of full conformity with the paschal Victim. On this special, happy occasion, I rejoice with the Archdiocese of Milan that benefited from his zealous activity, promoted his canonization, preserves his mortal remains and the place of his martyrdom. I cordially unite with the Sons of St Dominic who in him honour their first martyr, an exceptional model for consecrated persons and for the Christians of our time. 2. St Peter Martyr lived his whole life under the banner of the defence of the truth, expressed in the Apostles' "Creed", which he was in the habit of reciting from the age of seven, although he had been born into a family infiltrated by the Cathar heresy, and continued to proclaim "until his final moment" (cf. -

Mise En Page 1

Res novae-10-en.qxp 21/06/2019 09:13 Page 2 RES NOVAE ROMAN PERSPECTIVE - English Edition International monthly newsletter of analysis and prospective ❚ N° 10 ❚ June 2019 ❚ Année I ❚ 3 € Published in French, English and Italian INDEX Page 1 Card. Jorge Bergoglio ❚ Card. God- About the Bergoglian pontificate fried Danneels ❚ Card. Basil Hume ❚ Pope John-Paul II ❚ Card. Walter Kas- Part I - The Council, at full speed per ❚ Card. Karl Lehmann ❚ Card. Carlo Maria Martini ❚ Jürgen Mettepennin- ❚ ❚ gen Card. Joseph Ratzinger Karim oderate the Council or implement it : » it was the great Schelkens ❚ Card. Achille Silvestrini debate within the Church governing body since imme- Page 2 diately after the Council. But, after the failure of the Card. Jorge Bergoglio ❚ Pope Francis first option, the moderate one, with the resignation of ❚ Pope John-Paul II ❚ Card. Rodriguez “M Pope Ratzinger, are we not now seeing the failure of the second one ? Maradiaga ❚ Card. Carlo MariaMartini ❚ Card. Pietro Parolin ❚ Card. Paolo Ruf- Initially, a dual between Ratzinger and Martini ❚ ❚ fini Mgr Marcello Semeraro Père ❚ Antonio Spadaro Card. Beniamino K. Schelkens and J. Mettepenningen’s book titled Gottfried Danneels (An- Stella ❚ Mgr Dario Edoar do Viganó THE ÉDITORIAL vers, Polis, 2015) revealed that a number of cardinals (Lehman, Kasper, Sil- Page 3 vestrini, Hume, Danneels), were holding informal meetings in Saint-Gall, Card. Lorenzo Baldisseri ❚ Benoît XVI Switzerland, from 1996 to 2006, and were preparing an alternance to the ❚ Maurizio Chiodi ❚ Mgr Kevin Farrell Wojtylan pontificate, with the election of Cardinal Martini, Archbishop of ❚ Mgr Victor Manuel Fernandez Milan. The group around Martini, supported a full implementation of the ❚ Mgr Bruno Forte ❚ Pope Francis spirit of Vatican II, in opposition to the moderate option chosen by John- ❚ Mgr Chomali Garib ❚ Mgr Livio Me- Paul II, characterised as a « restoration » by its main author Cardinal Rat- lina ❚ Mgr Vincenzo Paglia ❚ Mgr Pie- zinger in the book The Ratzinger report (1985).