Pope Francis's Speech to Congress

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

POPE FRANCIS AS a GLOBAL ACTOR Where Politics and Theology Meet

POPE FRANCIS AS A GLOBAL ACTOR Where Politics and Theology Meet EDITED BY ALYNNA J. LYON, CHRISTINE A. GUSTAFSON, AND PAUL CHRISTOPHER MANUEL Palgrave Studies in Religion, Politics, and Policy Series editor Mark J. Rozell Schar School of Policy and Government George Mason University Arlington, VA, USA A generation ago, many social scientists regarded religion as an anachronism, whose social, economic, and political importance would inevitably wane and disap- pear in the face of the inexorable forces of modernity. Of course, nothing of the sort has occurred; indeed, the public role of religion is resurgent in US domestic politics, in other nations, and in the international arena. Today, religion is widely acknowledged to be a key variable in candidate nominations, platforms, and elections; it is recognized as a major influence on domestic and foreign policies. National religious movements as diverse as the Christian Right in the United States and the Taliban in Afghanistan are important factors in the internal politics of par- ticular nations. Moreover, such transnational religious actors as Al-Qaida, Falun Gong, and the Vatican have had important effects on the politics and policies of nations around the world. Palgrave Studies in Religion, Politics, and Policy serves a growing niche in the discipline of political science. This subfield has proliferated rapidly during the past two decades, and has generated an enormous amount of scholarly studies and journalistic coverage. Five years ago, the journal Politics and Religion was created; in addition, works relating to religion and politics have been the subject of many articles in more general academic journals. -

Edited by Conor Hill, Kent Lasnoski, Matthew Sherman, John Sikorski and Matthew Whelan

VOLUME 6, NUMBER 2 JUNE 2017 NEW WINE, NEW WINESKINS: PERSPECTIVES OF YOUNG MORAL THEOLOGIANS Edited by Conor Hill, Kent Lasnoski, Matthew Sherman, John Sikorski and Matthew Whelan Journal of Moral Theology is published semiannually, with issues in January and June. Our mission is to publish scholarly articles in the field of Catholic moral theology, as well as theological treatments of related topics in philosophy, economics, political philosophy, and psychology. Articles published in the Journal of Moral Theology undergo at least two double blind peer reviews. Authors are asked to submit articles electronically to [email protected]. Submissions should be prepared for blind review. Microsoft Word format preferred. The editors assume that submissions are not being simultaneously considered for publication in another venue. Journal of Moral Theology is indexed in the ATLA Catholic Periodical and Literature Index® (CPLI®), a product of the American Theological Library Association. Email: [email protected], www: http://www.atla.com. ISSN 2166-2851 (print) ISSN 2166-2118 (online) Journal of Moral Theology is published by Mount St. Mary’s University, 16300 Old Emmitsburg Road, Emmitsburg, MD 21727. Copyright© 2017 individual authors and Mount St. Mary’s University. All rights reserved. EDITOR EMERITUS AND UNIVERSITY LIAISON David M. McCarthy, Mount St. Mary’s University EDITOR Jason King, Saint Vincent College ASSOCIATE EDITOR William J. Collinge, Mount St. Mary’s University MANAGING EDITOR Kathy Criasia, Mount St. Mary’s University EDITORIAL BOARD Melanie Barrett, University of St. Mary of the Lake/Mundelein Seminary Jana M. Bennett, University of Dayton Mara Brecht, St. Norbert College Jim Caccamo, St. -

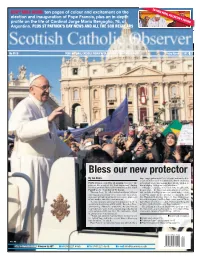

Bless Our New Protector

28-PAGE PAPAL COLLECTOR’S EDITION DON’T MISS INSIDE ten pages of colour and excitement on the election and inauguration of Pope Francis, plus an in-depth profile on the life of Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, 76, of Argentina. PLUS ST PATRICK’S DAY NEWS AND ALL THE SCO REGULARS No 5510 YOUR NATIONAL CATHOLIC NEWSPAPER SUPPORTS THE YEAR OF FAITH Friday March 22 2013 | £1 Bless our new protector By Ian Dunn huge congregation in St Peter’s Square and watched by a vast television audience around the world, including POPE Francis called for all mankind to serve ‘the in Scotland where our bishops have already written to poorest, the weakest, the least important,’ during him pledging ‘loving and loyal obedience.’ the inauguration Mass of his ministry as the 266th Although according to Church law, he officially Pontiff on the feast day of St Joseph. became Pope—the first Jesuit and Latin American Pon- The new Pope, 76, called in his homily for ‘all men tiff, and the first Pope from a religious order in 150 and women of goodwill’ to be ‘protectors of creation, years—the minute he accepted his election in the Sis- protectors of God’s plan inscribed in nature, protectors tine Chapel on Wednesday March 13, Pope Francis was of one another and of the environment.’ formally inaugurated as Holy Father at the start of Tues- “Let us not allow omens of destruction and death to day’s Mass, when he received the Fisherman’s Ring and accompany the advance of this world,” he said on Tues- pallium, symbolising his new Papal authority. -

![Mbiun [Library Ebook] Pope Francis: Conversations with Jorge Bergoglio: His Life in His Own Words Online](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4211/mbiun-library-ebook-pope-francis-conversations-with-jorge-bergoglio-his-life-in-his-own-words-online-2494211.webp)

Mbiun [Library Ebook] Pope Francis: Conversations with Jorge Bergoglio: His Life in His Own Words Online

MbiuN [Library ebook] Pope Francis: Conversations with Jorge Bergoglio: His Life in His Own Words Online [MbiuN.ebook] Pope Francis: Conversations with Jorge Bergoglio: His Life in His Own Words Pdf Free Francesca Ambrogetti, Sergio Rubin *Download PDF | ePub | DOC | audiobook | ebooks Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #450867 in Books Sergio Rubin Francesca Ambrogetti 2014-10-28 2014-10-28Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.22 x .66 x 5.44l, 1.00 #File Name: 0451469410304 pagesPope Francis Conversations with Jorge Bergoglio | File size: 53.Mb Francesca Ambrogetti, Sergio Rubin : Pope Francis: Conversations with Jorge Bergoglio: His Life in His Own Words before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Pope Francis: Conversations with Jorge Bergoglio: His Life in His Own Words: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. MUSICAL "TRIVIA"By VincentWe read Pope Francis' most admire musical composition Beethoven’s Leonore Overture No. 3, in the version by Wilhelm Furtwängler, who, as he sees it, is the finest conductor of certain of Beethoven’s symphonies and the works of Wagner. •••Yet, he would want to remember:I Corinthians 2:9 (...) "nor ear heard, nor the heart of man conceived, what God has prepared for those who love him."0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. ExcellentBy Les GapayExcellent book. Great insight into the now pope.1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. great background on how the Pope thinksBy DavidThis book gives much greater insight into who Pope Francis is. -

Libri Nuovi 2017 BIBLIOTECA SANT'alfonso

Libri nuovi 2017 BIBLIOTECA SANT’ALFONSO Via Merulana 31, Roma Catalogo: http://oseegenius2.urbe.it/alf/home Contatti: [email protected] - tel. 0649490214 FRANCESE Hi 62 327 Antoine Wenger, une traversée dans [Roma] : le XXème siècle et dans l'Église : [Assunzionisti], 2015. actes du Colloque d'Histoire, Rome, 5 décembre 2014 / édités par Bernard Le Léannec, A.A. Hi 55 566 Catholicisme en tensions / sous la Paris : Éditions de direction de Céline Béraud, Frédéric l'École des Hautes Gugelot et Isabelle Saint-Martin. Études en Sciences Sociales, 2012. Mo 415 1187 Choc démographique, rebond Paris : Descartes & économique / sous la direction de Cie, 2016. Jean-Hervé Lorenzi. SL 31 IV 34 Dictionnaire de la pensée Paris : Presses écologique / sous la direction de Universitaires de Dominique Bourg et Alain Papaux. France, 2015. SL 31 IV 33 Dictionnaire de la violence / publié Paris : Presses sous la direction de Michela Marzano. Universitaires de France, 2011. SL 41 II 8 Dictionnaire de psychologie / Norbert Paris : Larousse, Sillamy. 2010. SL 34 26 Dictionnaire du Vatican et du Saint- Paris : Robert Laffont, Siège / sous la direction de 2013. Christophe Dickès ; avec la collaboration de Marie Levant et Gilles Ferragu. SL 41 II 40/1- Dictionnaire fondamental de la Paris : Larousse, 2 psychologie / sous la direction de H. 2002. Bloch [ed altri 8] ; conseil éditorial Didier Casalis. Mo 427 225 Discriminations et carrières : Paris : Éditions entretiens sur des parcours de Noir-e- Pepper - s et d'Arabes / Alessio Motta (dir.) L'Harmattan, 2016. Mo 385 233 Le droit, le juste, l'équitable / sous la Paris : Salvator, 2014. direction de Simone Goyard et de Francis Jacques. -

Il Papa Dittatore

IL PAPA DITTATORE Marcantonio Colonna Potete ingannare tutti per qualche tempo, o alcuni sempre, ma non potete ingannare tutti per sempre. Abramo Lincoln INDICE Introduzione 1. La Mafia di San Gallo 2. Il Cardinale dall’Argentina 3. Riforma? Quale riforma? Illustrazioni 4. Aprire una nuova (ambigua) strada 5. Misericordia! Misericordia! 6. Cremlino Santa Marta Introduzione Se parlate con i Cattolici di Buenos Aires, essi vi racconteranno della trasformazione miracolosa che si è prodotta in Jorge Mario Bergoglio. Il loro arcivescovo cupo e serio si è trasformato in una notte nel sorridente e allegro Papa Francesco, l’idolo della gente con la quale si è completamente identificato. Se parlate con chi lavora in Vaticano, vi racconteranno del miracolo in senso inverso. Quando le telecamere della televisione non lo inquadrano, Papa Francesco si trasforma in un’altra persona: arrogante, scostante con le persone, volgare nel parlare e famoso per i violenti scoppi d’ira che sono ben conosciuti a tutti, dai cardinali agli autisti. Come lo stesso Papa Francesco ha detto nella sera della sua elezione, i cardinali nel conclave del marzo 2013 sembra che abbiano deciso di andare “ai confini della Terra” per scegliere il loro papa, ma cresce ormai la percezione che non si siano dati granché da fare per controllare la loro merce. Al principio, egli sembrava essere un soffio d’aria fresca, essendo il suo rifiuto delle convenzioni il segno di un uomo che avrebbe messo in atto una riforma audace e radicale nella Chiesa. Nel quinto anno del suo pontificato sta diventando sempre più chiaro che la riforma non sarà fatta. -

Pope Francis's Strong Thought

JULY 2014: VOLUME 7, NUMBER 2 • THEOLOGICAL LIBRARIANSHIP Pope Francis’s Strong Thought by Keith Edward Lemna Does a literature review of the most serious writings about or from Pope Francis confirm him to be a champion of “pragmatic” Christianity in the mold of “weak thought”? “Weak thought” (pensiero debole), the invention of the Italian atheist and nihilist Catholic Gianni Vattimo, is the most self-aware and logically consistent form of contemporary, progressive Christian (a-)theology.1 It is, of course, not known to the run of journalists or editorialists in the English- speaking world. Nevertheless, “weak thought” underlies the prospect for the Catholic Church’s future that journalists and media personalities, not to mention many Catholic academicians, thrill to when they assess Pope Francis. “Weak thought” would empty the counsels of the Roman Catholic Church of any claim to divinely given authority, whether to teach, to preach, or to sanctify through the communion of its sacraments. “Weak thinking” by the Catholic bishops, united to the Bishop of Rome, would disclaim definitive interpretation of the Gospel, and for that reason would constitute, on Vattimo’s account, a profoundly Christian configuration to the self-emptying or kenosis of Christ on Calvary, whereby he himself definitively gave up all claims to the prerogatives of divinity. Consequently, “weak thought” should lead the Church to reinterpret its teachings in the arena of marriage, family, “gender,” and life issues. Where the Church’s traditional teaching enters into sharpest conflict with present-day European and North American social norms, there “weak thinking” will resign the “metaphysical violence” of Überwindung — of “overcoming” — in favor of Verwindung — of “tension,” “twisting,” “accommodation,” “healing.” “Weak thought” privatizes religion, moving it away from adherence to authoritative norms or principles and in the direction of social dialogue and edification. -

Highlights of CWCIT Events Distinguished Speakers About Us

About Us The Center for World Catholicism and Intercultural Theology (CWCIT) seeks to be at the forefront of the discussion about the relationship between globalization and the Catholic Church’s future as a truly worldwide In 1900, only 25 percent of Catholics lived in the global South: Church. Latin America, Asia, and Africa. Housed in the Department of Catholic Studies at By the year 2000, DePaul University, CWCIT focuses especially but not exclusively on the Church in the global South (Asia, that number had shifted to nearly 70 percent. Africa, and Latin America). We seek to create channels of collaboration and friendship among scholars from the North and South; to that end, each year we host visiting scholars from the global South. In addition to being mutually beneficial and enriching, this intercultural intercambio, like the work of CWCIT itself, Highlights of CWCIT Events Distinguished Speakers promotes tolerance and genuine bonds of solidarity CWCIT offers numerous lectures and other events for students, between people whose particular cultural histories may faculty/staff, and the broader community, including its annual con- be in conflict. ference, World Catholicism Week, which brings together numerous Rev. Laurenti Magesa international scholars each April. The following are highlights of Pioneering author & scholar in African Catholicism Professor, Hekima University College & Tangaza University past events: College (Nairobi, Kenya) Muslim-Catholic Dialogue Series (2015-2016) Focusing on Africa, the Middle East, and the Philippines, this series brought together Muslim and Catholic leaders of interfaith dialogue Sister Helen Prejean, CSJ Mission Statement to discuss the theological resources—as well as practical, on-the- Anti-death penalty advocate ground strategies—that they have found fruitful in regions of the Author, Dead Man Walking CWCIT was founded by DePaul University in 2008 in world where this dialogue can truly mean the difference between order to produce research that will serve the Church life and death. -

Pope Francis's Critique of Globalisation and Neoliberal Capitalism

Pope Francis’s Call for Social Justice in the Global Economy Bruce Duncan Pope Francis sparked accusations that he is espousing Marxism in his November 2013 exhortation, The Joy of the Gospel, because of his pointed attacks on economic liberalism or neoliberalism, the ideology behind versions of free-market economics.1 The conservative US radio commentator, Rush Limbaugh, with a following of 20 million listeners on a program valued at $400 million, accused the Pope of sprouting ‘pure Marxism’, and of not knowing what he was talking about.2 Pope Francis responded that he was merely articulating church social teaching. ‘The Marxist ideology is wrong. But I have met many Marxists in my life who are good people, so I don’t feel offended.’ He said his critique of ‘trickle down theories’ of economics referred to those that did nothing for the poor.3 On 20 September Francis had said that ‘Jesus emphasises so much that the love of money, in fact, is the root of all evil. “You cannot serve both God and money” ’. This ‘was not communism! This is pure Gospel!’4 Francis is highlighting problems of deep poverty in many countries and vast inequalities in the distribution of wealth. He welcomes the material uplift for millions of people in recent decades, but is strongly critical that millions of others are trapped in grinding poverty. In a time when we have such an abundance of material resources, he is calling for economic initiatives to lift remaining populations out of hunger and extreme poverty. * Within months of being unexpectedly elected Bishop of Rome, Pope Francis has attracted a wide following, and not just among Catholics. -

Fifty Years After His Ordination, Pope Francis’ Priestly Vocation Is His Favourite Gift

Fifty years after his ordination, Pope Francis’ priestly vocation is his favourite gift In Caravaggio’s painting of Matthew, the sinful tax collector being called by Jesus to “Follow me,” Pope Francis sees the same unexpected, grace-filled moment found in his own call to the priesthood. A 17-year-old Argentine student headed to a school picnic on Sept. 21, 1953, the feast of St. Matthew, Jorge Bergoglio felt compelled to first stop by his parish of San Jose de Flores. It was there, speaking with a priest he had never seen before and receiving the sacrament of reconciliation, he was suddenly struck by “the loving presence of God,” who, like his episcopal motto describes, saw him through eyes of mercy and chose him, despite his human imperfections and flaws. This gift from a “God of surprises,” a God who offers unexpected, unlimited and unmerited mercy, would change the young man’s life. On Dec. 13 – four days before his 83rd birthday – Pope Francis celebrates 50 years as a priest. It’s a ministry he sees as being a shepherd who walks with his flock and yearns to find those who are lost. The Vatican stamp and coin office released these special stamps to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Pope Francis' Dec. 13, 1969, ordination to the priesthood.Catholic News Service Even though he served as auxiliary bishop, then archbishop of Buenos Aires, Argentina, for more than 20 years, was elevated to the College of Cardinals in 2001 and elected pope in 2013, he has said, “What I love is being a priest,” which is why of all the titles he could have, “I prefer to be called ‘Father.'” So much of what Pope Francis experienced in life and his vocation – with its many ups and downs – influenced what he says today about the priesthood, what it means and what it should be for the Church. -

Highlights of CWCIT Events

About Us The Center for World Catholicism and Intercultural Theology (CWCIT) seeks to be at the forefront of the discussion about the relationship between globalization and the Catholic Church’s future as In 1900, only 25 percent of Catholics lived in the global South: a truly worldwide Church. Latin America, Asia, and Africa. Questions of peacemaking and social reconciliation inform our work and academic research, and to that By the year 2000, end, each year we host several visiting theological that number had shifted to nearly 70 percent. scholars from the global South. In addition to being mutually beneficial and enriching, this intercultural intercambio, like the work of CWCIT itself, promotes tolerance and genuine bonds of solidarity between people whose particular cultural histories are in conflict. Highlights of CWCIT Events Distinguished Speakers While there is no philosopher’s stone, no “quick Throughout the year, CWCIT offers numerous lectures, roundta- fix”, to end global conflicts or resolve long-standing bles, and other events for students, faculty/staff, and the broader theological arguments, CWCIT strives to promote a community. And each April, CWCIT hosts numerous international conciliatory tone in the midst of such strife through scholars for World Catholicism Week, a celebration of the globally John Allen The Boston Globe the highest quality academic research. interdependent dimensions of the Catholic experience of faith. Associate Editor, & Crux Here are some highlights of past events: Senior Vatican Analyst, CNN Mission Statement Intercontinental Conference in Manila (Dec. 2014) With speakers from the Philippines, U.S., and Australia, Sister Helen Prejean, CSJ CWCIT was founded by DePaul University in 2008 in “Theology, Conflict, and Peacebuilding” was CWCIT’s second Anti-death penalty advocate conference abroad; it was co-sponsored with Adamson University, Author, Dead Man Walking order to produce research that will serve the Church the St. -

Making of Pope Francis

JNANADEEPA PJRS ISSN 0972-3331 22/1 Jan-June 2018: 11-32 Making of Pope Francis Jacob Naluparayil MCBS Smart Companion, Kochi Abstract: Jorge Mario Bergoglio known as Pope Francis today is a unique gift to God. He stepped in at a moment when the Church was feeling very low with a dwindling self-esteem, fragile and defenseless, her moral authority challenged from within and out. He was chosen by God to guide his Church as a sacrament of God’s mercy and forgiving love and to rejuvenate the Church to be powerful witness of God’s kingdom. A brief life sketch of Pope Francis and an analysis of the events and experiences that molded and formed Pope Francis, a leader of unprecedented courage and qualities would show that this person is gifted to the Church by the Lord to renew the Church and re-awaken its mission to be the light and the salt of the earth. His self-awareness of his weaknesses and strengths, his complete trust in the providential care of the Lord and renewing power of the Spirit, his lived experience of Ignatian spiri- tuality help him to guide the Church through dialogue, discernment and de-centralization. Pope Francis has brought in revolutionary change in Church, attitudes, approach and style in relating with those within the Church as well as outside the Church. In spite of considerable resistance, such attitudinal and stylistic changes have evoked greater confidence, hope and enthusiasm in the ordinary believers and a greater acceptance of Pope’s spiritual and moral leadership by the entire world.