POPE FRANCIS AS a GLOBAL ACTOR Where Politics and Theology Meet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cómo Citar El Artículo Número Completo Más Información Del

deSignis ISSN: 1578-4223 ISSN: 2462-7259 [email protected] Federación Latinoamericana de Semiótica Organismo Internacional Manuel Corvalán Espina, Juan Religión católica, nuevas tecnologías y redes sociales virtuales: ¿Configura populismo la comunicación del Papa Francisco en la era del Internet 2.0? deSignis, vol. 31, 2019, Julio-, pp. 339-357 Federación Latinoamericana de Semiótica Organismo Internacional DOI: https://doi.org/10.35659/designis.i31p339-357 Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=606064169022 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Redalyc Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto http://dx.doi.org/10.35659/designis.i31p339-357 RELIGIÓN CATÓLICA, NUEVAS TECNOLOGÍAS Y REDES SOCIALES VIRTUALES: ¿CONFIGURA POPULISMO LA COMUNICACIÓN DEL PAPA FRANCISCO EN LA ERA DEL INTERNET 2.0? Religión católica, nuevas tecnologías y redes sociales virtuales: ¿Configura populismo la comunicación del Papa Francisco en la era del Internet 2.0? Catholic Religion, new technologies and virtual networks: Pope Francisco’s communication style in Internet Era 2.0 Juan Manuel Corvalán Espina (pág 339 - pág 357) El presente trabajo busca contribuir al estudio del populismo y el liderazgo. Se concentra en el proceso por medio del cual, una institución tradicional como la Iglesia Católica Apostólica Romana adapta sus mecanismos de comunicación a fin de ajustarse a los desafíos que presentan los desarrollos tecnológicos y la utilización de las redes sociales virtuales a nivel mundial. Este artículo examina la evolución de la circulación mediática del mensaje de la Iglesia a través de su órgano gobernante, la Santa Sede, así como también el uso que los distintos pontífices hacen de las nuevas tecnologías, en particular, las redes sociales virtuales. -

L'o S S E Rvator E Romano

Price € 1,00. Back issues € 2,00 L’O S S E RVATOR E ROMANO WEEKLY EDITION IN ENGLISH Unicuique suum Non praevalebunt Fifty-third year, number 19 (2.646) Vatican City Friday, 8 May 2020 Higher Committee of Human Fraternity calls to join together on 14 May A day of prayer, fasting and works of charity The Holy Father has accepted the proposal of the Higher Commit- tee of Human Fraternity to call for a day of prayer, of fasting and works of charity on Thursday, 14 May, to be observed by all men and women “believers in God, the All-Creator”. The proposal is addressed to all religious leaders and to people around the world to implore God to help humanity overcome the coronavirus (Covid- 19) pandemic. The appeal released on Sat- urday, 2 May, reads: “Our world is facing a great danger that threatens the lives of millions of people around the world due to the growing spread of the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic. While we reaffirm the role of medicine and scientific research in fighting this pandemic, we should not forget to seek refuge in God, the All-Creator, as we face such severe crisis. Therefore, we call on all peoples around the world to do good deeds, observe fast, pray, and make devout sup- plications to God Almighty to end this pandemic. Each one from wherever they are and ac- cording to the teachings of their religion, faith, or sect, should im- plore God to lift this pandemic off us and the entire world, to rescue us all from this adversity, to inspire scientists to find a cure that can turn back this disease, and to save the whole world from the health, economic, and human repercussions of this serious pan- demic. -

Mission Statement

ROBERT B. MOYNIHAN, PH.D ITV MAGAZINE EDITORIAL OFFICES URBI ET ORBI COMMUNICATIONS PHONE: 1-443-454-3895 PHONE: (39)(06) 39387471 PHONE: 1-270-325-5499 [email protected] FAX: (39)(06) 6381316 FAX: 1-270-325-3091 14 WEST MAIN STREET ANGELO MASINA, 9 6375 NEW HOPE ROAD FRONT ROYAL, VA 22630 00153 ROME ITALY P.O. BOX 57 USA NEW HOPE, KY 40052 USA p u d l b r l i o s h w i e n h g t t Résumé for Robert Moynihan, PhD r o t u t d h n a to y Education: the cit • Yale University: Ph.D., Medieval Studies, 1988, M.Phil., 1983, M.A., 1982 Mission Statement • Gregorian University (Rome, Italy): Diploma in Latin Letters, 1986 To employ the written and • Harvard College: B.A., magna cum laude, English, 1977 spoken word in order to defend the Christian faith, and to spread Ph.D. thesis: the message of a Culture of Life • The Influence of Joachim of Fiore on the Early Franciscans: A Study of the Commentary Super to a fallen world desperately in need of the saving truth of the Hieremiam; Advisor: Prof. Jaroslav Pelikan, Reader: Prof. John Boswell Gospel of Christ. Academic Research fields: • History of Christianity • Later Roman Empire • The Age of Chaucer . Contributors include: The Holy See in Rome, Professional expertise: especially the Pontifical Council for Culture Modern History of the Church and the Holy See, with a specialty in Vatican affairs, The Russian Orthodox Church from the Second Vatican Council (1962-65) to the present day. -

US Recognizes Vatican's Financial Regulations on Client Verification - Vati

US recognizes Vatican's financial regulations on client verification - Vati... https://www.vaticannews.va/en/vatican-city/news/2021-06/united-states-i... Allegro vivace Podcast Programs ~VATICAN ~ NEWS ~= VATICAN VATICAN HOLY SEE UNITED STATES US recognizes Vatican·s financial regulations on client verification According to the website of the US Internal Revenue Service, the Holy See and the Vatican City State have just been listed among the equivalent jurisdictions in terms of financial security and know-your-customer rules. By Vatican News The laws of the Vatican City State and the Holy See which have strengthened transparency◄~ and financial oversight in recent years continue to gain international recognition, including 1 of 2 6/4/2021, 11:30 AM US recognizes Vatican's financial regulations on client verification - Vati... https://www.vaticannews.va/en/vatican-city/news/2021-06/united-states-i... from the United States. The Internal Revenue Service (IRS), the US government agency responsible for collecting federal taxes, published its recognition in recent days on its website. The Vatican is now listed among the jurisdictions which have auditing rules for financial security that conform to the best international standards. The United States has therefore recognized that the Vatican's know-your-customer rules are equivalent to its own. The .S.P-ecific annex dedicated to the Holy See and the Vatican City State explicitly mentions the laws and regulations that govern the requirements to obtain documentation to unequivocally confirm the identity of account holders in the Vatican. It also cites Law No. XVIII of 8 October 2013, amended by Law No. -

Edited by Conor Hill, Kent Lasnoski, Matthew Sherman, John Sikorski and Matthew Whelan

VOLUME 6, NUMBER 2 JUNE 2017 NEW WINE, NEW WINESKINS: PERSPECTIVES OF YOUNG MORAL THEOLOGIANS Edited by Conor Hill, Kent Lasnoski, Matthew Sherman, John Sikorski and Matthew Whelan Journal of Moral Theology is published semiannually, with issues in January and June. Our mission is to publish scholarly articles in the field of Catholic moral theology, as well as theological treatments of related topics in philosophy, economics, political philosophy, and psychology. Articles published in the Journal of Moral Theology undergo at least two double blind peer reviews. Authors are asked to submit articles electronically to [email protected]. Submissions should be prepared for blind review. Microsoft Word format preferred. The editors assume that submissions are not being simultaneously considered for publication in another venue. Journal of Moral Theology is indexed in the ATLA Catholic Periodical and Literature Index® (CPLI®), a product of the American Theological Library Association. Email: [email protected], www: http://www.atla.com. ISSN 2166-2851 (print) ISSN 2166-2118 (online) Journal of Moral Theology is published by Mount St. Mary’s University, 16300 Old Emmitsburg Road, Emmitsburg, MD 21727. Copyright© 2017 individual authors and Mount St. Mary’s University. All rights reserved. EDITOR EMERITUS AND UNIVERSITY LIAISON David M. McCarthy, Mount St. Mary’s University EDITOR Jason King, Saint Vincent College ASSOCIATE EDITOR William J. Collinge, Mount St. Mary’s University MANAGING EDITOR Kathy Criasia, Mount St. Mary’s University EDITORIAL BOARD Melanie Barrett, University of St. Mary of the Lake/Mundelein Seminary Jana M. Bennett, University of Dayton Mara Brecht, St. Norbert College Jim Caccamo, St. -

On the Touch-Event Theopolitical Encounters

ON THE TOUCH-EVENT Theopolitical Encounters Valentina Napolitano Abstract: This article addresses the ‘touch-event’ as a mediated affective encounter that pivots around a tension between intimacy and distance, seduction and sovereignty, investment and withdrawal. Through a reread- ing of the Pauline event of conversion to Christianity, it argues that an analysis of the evolving significance of touch-events for Catholic liturgy and a religious congregation shows the theopolitical as always already constituted within an economy of enfleshed virtues. Focusing on contem- porary examples of touch-events from the life of Francis, the first pope from the Americas, as well as from fieldwork among a group of female Latin American Catholic migrants in Rome, I argue for a closer examina- tion of touch-events in order to grasp some of their theopolitical, radical, emancipatory, and, in some contexts, subjugating effects. Keywords: Atlantic Return, economies of virtues, incarnation, Pauline event, Pope Francis, sovereignty, theopolitics, touch-event If one googles the word ‘touch-event’, what comes up is a definition of a keyword in the Java programming language—TouchEvent—that governs the interface between a given piece of software and a user’s contact with a piece of touch-sensitive hardware (e.g., a touchscreen or touchpad).1 Although this use of the term is distinct in obvious ways from my own theorization of touch- event in what follows, the Java keyword ‘TouchEvent’ nevertheless names an infrastructural modality that is at once a tactile, digital encounter (a move- ment) and a condition for its apprehension (a code). Anthropologists and histo- rians have written at some length about touch—chief touch, royal touch, papal touch, ritual and healing touch—and the connection between the king’s two bodies in medieval and early modern concepts of sovereignty (Firth 1940; Grae- ber and Sahlins 2017; Kantorowicz [1957] 1997). -

Roman Catholic Leadership And/In Religions for Peace Synopsis Prepared in 2020 Table of Contents I

Roman Catholic Leadership and/in Religions for Peace Synopsis Prepared in 2020 Table of Contents I. Current Roman Catholic Leadership in Religions for Peace International II. History of Roman Catholic Leadership in Religions for Peace Global Movement III. Milestones in the RfP - Vatican/Holy See Joint Journeys IV. Regional Spotlights - Common Purpose and Engagement between RfP mission and Catholic Leadership I. Current Roman Catholic Leadership in Religions for Peace International WORLD COUNCIL H.E. Cardinal Charles Bo, Archbishop of Yangon, Myanmar; President, Federation of Asian Bishops’ Conference H.E. Cardinal Blasé J. Cupich, Archbishop of Chicago, United States H.E. Cardinal Dieudonné Nzapalainga, Archbishop of Bangui, Central African Republic H.E. Philippe Cardinal Ouédraogo, Archbishop of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso; President, Symposium of African and Madagascar Bishops’ Conference (SECAM) H.E. Cardinal Luis Antonio Tagle, Prefect of the Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples Ms. Maria Lia Zervino, President General, World Union of Catholic Women’s Organizations, Argentina HONORARY PRESIDENTS H.E. Cardinal John Onaiyekan, Archbishop Emeritus of Abuja, Nigeria; Co-Chair, African Council of Religious Leaders-RfP H.E. Cardinal Vinko Puljić, Archbishop of Vrhbosna, Bosnia-Herzegovina Emmaus Maria Voce, President, Movimento Dei Focolari, Italy 777 United Nations Plaza | New York, NY 10017 USA | Tel: 212 687-2163 | www.rfp.org 1 | P a g e LEADERSHIP H.E. Cardinal Raymundo Damasceno Assis, Archbishop Emeritus of Aparecida, Sao Paulo, Brazil; Moderator, Religions for Peace-Latin America and Caribbean Council of Religious Leaders Rev. Sr. Agatha Ogochukwu Chikelue, Nun of the Daughters of Mary Mother of Mercy; Co- Chair Nigerian & African Women of Faith Network; Executive Director Cardinal Onaiyekan Foundation for Peace (COFP) II. -

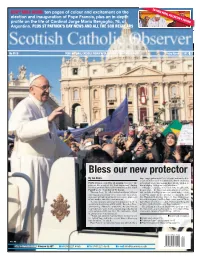

Bless Our New Protector

28-PAGE PAPAL COLLECTOR’S EDITION DON’T MISS INSIDE ten pages of colour and excitement on the election and inauguration of Pope Francis, plus an in-depth profile on the life of Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio, 76, of Argentina. PLUS ST PATRICK’S DAY NEWS AND ALL THE SCO REGULARS No 5510 YOUR NATIONAL CATHOLIC NEWSPAPER SUPPORTS THE YEAR OF FAITH Friday March 22 2013 | £1 Bless our new protector By Ian Dunn huge congregation in St Peter’s Square and watched by a vast television audience around the world, including POPE Francis called for all mankind to serve ‘the in Scotland where our bishops have already written to poorest, the weakest, the least important,’ during him pledging ‘loving and loyal obedience.’ the inauguration Mass of his ministry as the 266th Although according to Church law, he officially Pontiff on the feast day of St Joseph. became Pope—the first Jesuit and Latin American Pon- The new Pope, 76, called in his homily for ‘all men tiff, and the first Pope from a religious order in 150 and women of goodwill’ to be ‘protectors of creation, years—the minute he accepted his election in the Sis- protectors of God’s plan inscribed in nature, protectors tine Chapel on Wednesday March 13, Pope Francis was of one another and of the environment.’ formally inaugurated as Holy Father at the start of Tues- “Let us not allow omens of destruction and death to day’s Mass, when he received the Fisherman’s Ring and accompany the advance of this world,” he said on Tues- pallium, symbolising his new Papal authority. -

Vatican Secret Diplomacy This Page Intentionally Left Blank Charles R

vatican secret diplomacy This page intentionally left blank charles r. gallagher, s.j. Vatican Secret Diplomacy joseph p. hurley and pope pius xii yale university press new haven & london Disclaimer: Some images in the printed version of this book are not available for inclusion in the eBook. Copyright © 2008 by Yale University. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Scala and Scala Sans by Duke & Company, Devon, Pennsylvania. Printed in the United States of America by Sheridan Books, Ann Arbor, Michigan. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gallagher, Charles R., 1965– Vatican secret diplomacy : Joseph P. Hurley and Pope Pius XII / Charles R. Gallagher. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-300-12134-6 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Hurley, Joseph P. 2. Pius XII, Pope, 1876–1958. 3. World War, 1939–1945— Religious aspects—Catholic Church. 4. Catholic Church—Foreign relations. I. Title. BX4705.H873G35 2008 282.092—dc22 [B] 2007043743 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Com- mittee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 To my father and in loving memory of my mother This page intentionally left blank contents Acknowledgments ix Introduction 1 1 A Priest in the Family 8 2 Diplomatic Observer: India and Japan, 1927–1934 29 3 Silencing Charlie: The Rev. -

THE USE of NEW MEDIA in the CATHOLIC CHURCH Imrich Gazda, Albert Kulla: the USE of NEW MEDIA in the CATHOLIC CHURCH Informatol

Imrich Gazda, Albert Kulla: THE USE OF NEW MEDIA IN THE CATHOLIC CHURCH Imrich Gazda, Albert Kulla: THE USE OF NEW MEDIA IN THE CATHOLIC CHURCH Informatol. 46, 2013., 3, 232-239 232 Informatol. 46, 2013., 3, 232-239 INFO- 2092 UDK : 316.77:28:007 Table 1: The use of social media by Dalai Lama (on May 21, 2013) Primljeno / Received: 2013-04-17 Prethodno priopćenje/Preliminary Communication Social medium Name of the Ac- Date Number of Follow- cunt ers THE USE OF NEW MEDIA IN THE CATHOLIC CHURCH Facebook Dalai Lama March 3, 2010 5,111,973 KORIŠTENJE NOVIH MEDIJA U KATOLIČKOJ CRKVI YouTube Dalai Lama March 12, 2010 25,163 Imrich Gazda, Albert Kulla Twitter @DalaiLama April 20, 2010 7,021,274 Department of Journalism, Faculty of Arts and Letters, The Catholic University in Ružomberok, Ružomberok, Slovakia Google + Dalai Lama November 7, 2011 3,518,018 Katoličko sveučilište u Ružomberoku, Ružomberok, Slovačka Abstract Sažetak A driving engine these days is not manual work, Pokretač danas nije ručni rad, snaga pare i elek- Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia Twitter since November 27, 2012. He has had 147 steam power or electricity, but information. Social trične energije, nego informacije. Društveni i gos- (secular name Vladimir M. Gundyaev) has been tweets in English and in Arabian in total. His ac- and economic life is especially based on for- podarski života pogotovo, temelje se na formira- active on facebook since May 15, 2012. Until May count @PopeTawadros has 54,417 followers. mation, searching for and classification of infor- nju, traženju i klasifikaciji podataka. -

Pope Creates 13 New Cardinals, Including Washington Archbishop

Pope creates 13 new cardinals, including Washington archbishop VATICAN CITY (CNS) — One by one 11 senior churchmen, including two U.S. citizens — Cardinals Wilton D. Gregory of Washington and Silvano M. Tomasi, a former Vatican diplomat — knelt before Pope Francis to receive their red hats, a cardinal’s ring and a scroll formally declaring their new status and assigning them a “titular” church in Rome. But with the consistory Nov. 28 occurring during the COVID-19 pandemic, Pope Francis actually created 13 new cardinals. Cardinals Jose F. Advincula of Capiz, Philippines, and Cornelius Sim, apostolic vicar of Brunei, did not attend the consistory because of COVID-19 travel restrictions; however, they are officially cardinals and will receive their birettas and rings at a later date, the Vatican said. In his homily at the prayer service, Pope Francis told the new cardinals that “the scarlet of a cardinal’s robes, which is the color of blood, can, for a worldly spirit, become the color of a secular ’eminence,'” the traditional title of respect for a cardinal. If that happens, he said, “you will no longer be a pastor close to your people. You will think of yourself only as ‘His Eminence.’ If you feel that, you are off the path.” For the cardinals, the pope said, the red must symbolize a wholehearted following of Jesus, who willingly gave his life on the cross to save humanity. The Gospel reading at the service, Mark 10:32-45, included the account of James and John asking Jesus for special honors. “Grant that in your glory we may sit one at your right and the other at your left,” they said. -

Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Catholicism, 1932-1936. George Quitman Flynn Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1966 Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Catholicism, 1932-1936. George Quitman Flynn Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Flynn, George Quitman, "Franklin D. Roosevelt and American Catholicism, 1932-1936." (1966). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1123. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1123 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 66-6443 FLYNN, George Quitman, 1937- FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT AND AMERICAN CATHOLICISM, 1932-1936. Louisiana State University, Ph.D., 1966 History, modem University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan FRANKLIN D. ROOSEVELT AND AMERICAN CATHOLICISM, 1932-1936 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of History by George Quitman Flynn B.S., Loyola University of the South, 1960 M.A., Louisiana State University, 1962 January, 1966 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The author wishes to thank Professor Burl Noggle for his assistance in directing this dissertation. Due to the author's military obligation, much of the revision of this dissertation was done by mail. Because of Professor Noggle's promptness in reviewing and returning the manuscript, a situation which could have lengthened the time required to complete the work proved to be only a minor inconvenience.