The Rotator Cuff by Tim Bertelsman & Brandon Steele

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Entheseal Changes: Definition and Life Course Changes Sébastien Villotte, Christopher J

Understanding Entheseal Changes: Definition and Life Course Changes Sébastien Villotte, Christopher J. Knüsel To cite this version: Sébastien Villotte, Christopher J. Knüsel. Understanding Entheseal Changes: Definition and Life Course Changes. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, Wiley, 2013, Entheseal Changes and Occupation: Technical and Theoretical Advances and Their Applications, 23 (2), pp.135-146. 10.1002/oa.2289. hal-03147090 HAL Id: hal-03147090 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-03147090 Submitted on 19 Feb 2021 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology Understanding Entheseal Changes: Definition and Life Course Changes Journal: International Journal of Osteoarchaeology Manuscript ID: OA-12-0089.R1 Wiley - ManuscriptFor type: Commentary Peer Review Date Submitted by the Author: n/a Complete List of Authors: Villotte, Sébastien; University of Bradford, AGES Knusel, Chris; University of Exeter, Department of Archaeology entheses, enthesopathy, Musculoskeletal Stress Markers (MSM), Keywords: senescence, activity, hormones, animal models, clinical studies http://mc.manuscriptcentral.com/oa Page 1 of 27 International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 1 2 3 Title: 4 5 Understanding Entheseal Changes: Definition and Life Course Changes 6 7 8 Short title: 9 10 Understanding Entheseal Changes 11 12 13 Keywords: entheses; enthesopathy; Musculoskeletal Stress Markers (MSM); senescence; 14 15 activity; hormones; animal models; clinical studies 16 17 18 Authors: For Peer Review 19 20 Villotte S. -

Juvenile Spondyloarthropathies: Inflammation in Disguise

PP.qxd:06/15-2 Ped Perspectives 7/25/08 10:49 AM Page 2 APEDIATRIC Volume 17, Number 2 2008 Juvenile Spondyloarthropathieserspective Inflammation in DisguiseP by Evren Akin, M.D. The spondyloarthropathies are a group of inflammatory conditions that involve the spine (sacroiliitis and spondylitis), joints (asymmetric peripheral Case Study arthropathy) and tendons (enthesopathy). The clinical subsets of spondyloarthropathies constitute a wide spectrum, including: • Ankylosing spondylitis What does spondyloarthropathy • Psoriatic arthritis look like in a child? • Reactive arthritis • Inflammatory bowel disease associated with arthritis A 12-year-old boy is actively involved in sports. • Undifferentiated sacroiliitis When his right toe starts to hurt, overuse injury is Depending on the subtype, extra-articular manifestations might involve the eyes, thought to be the cause. The right toe eventually skin, lungs, gastrointestinal tract and heart. The most commonly accepted swells up, and he is referred to a rheumatologist to classification criteria for spondyloarthropathies are from the European evaluate for possible gout. Over the next few Spondyloarthropathy Study Group (ESSG). See Table 1. weeks, his right knee begins hurting as well. At the rheumatologist’s office, arthritis of the right second The juvenile spondyloarthropathies — which are the focus of this article — toe and the right knee is noted. Family history is might be defined as any spondyloarthropathy subtype that is diagnosed before remarkable for back stiffness in the father, which is age 17. It should be noted, however, that adult and juvenile spondyloar- reported as “due to sports participation.” thropathies exist on a continuum. In other words, many children diagnosed with a type of juvenile spondyloarthropathy will eventually fulfill criteria for Antinuclear antibody (ANA) and rheumatoid factor adult spondyloarthropathy. -

9 Impingement and Rotator Cuff Disease

Impingement and Rotator Cuff Disease 121 9 Impingement and Rotator Cuff Disease A. Stäbler CONTENTS Shoulder pain and chronic reduced function are fre- quently heard complaints in an orthopaedic outpa- 9.1 Defi nition of Impingement Syndrome 122 tient department. The symptoms are often related to 9.2 Stages of Impingement 123 the unique anatomic relationships present around the 9.3 Imaging of Impingement Syndrome: Uri Imaging Modalities 123 glenohumeral joint ( 1997). Impingement of the 9.3.1 Radiography 123 rotator cuff and adjacent bursa between the humeral 9.3.2 Ultrasound 126 head and the coracoacromial arch are among the most 9.3.3 Arthrography 126 common causes of shoulder pain. Neer noted that 9.3.4 Magnetic Resonance Imaging 127 elevation of the arm, particularly in internal rotation, 9.3.4.1 Sequences 127 9.3.4.2 Gadolinium 128 causes the critical area of the cuff to pass under the 9.3.4.3 MR Arthrography 128 coracoacromial arch. In cadaver dissections he found 9.4 Imaging Findings in Impingement Syndrome alterations attributable to mechanical impingement and Rotator Cuff Tears 130 including a ridge of proliferative spurs and excres- 9.4.1 Bursal Effusion 130 cences on the undersurface of the anterior margin 9.4.2 Imaging Following Impingement Test Injection 131 Neer Neer 9.4.3 Tendinosis 131 of the acromion ( 1972). Thus it was who 9.4.4 Partial Thickness Tears 133 introduced the concept of an impingement syndrome 9.4.5 Full-Thickness Tears 134 continuum ranging from chronic bursitis and partial 9.4.5.1 Subacromial Distance 136 tears to complete tears of the supraspinatus tendon, 9.4.5.2 Peribursal Fat Plane 137 which may extend to involve other parts of the cuff 9.4.5.3 Intramuscular Cysts 137 Neer Matsen 9.4.6 Massive Tears 137 ( 1972; 1990). -

Rotator Cuff and Subacromial Impingement Syndrome: Anatomy, Etiology, Screening, and Treatment

Rotator Cuff and Subacromial Impingement Syndrome: Anatomy, Etiology, Screening, and Treatment The glenohumeral joint is the most mobile joint in the human body, but this same characteristic also makes it the least stable joint.1-3 The rotator cuff is a group of muscles that are important in supporting the glenohumeral joint, essential in almost every type of shoulder movement.4 These muscles maintain dynamic joint stability which not only avoids mechanical obstruction but also increases the functional range of motion at the joint.1,2 However, dysfunction of these stabilizers often leads to a complex pattern of degeneration, rotator cuff tear arthropathy that often involves subacromial impingement.2,22 Rotator cuff tear arthropathy is strikingly prevalent and is the most common cause of shoulder pain and dysfunction.3,4 It appears to be age-dependent, affecting 9.7% of patients aged 20 years and younger and increasing to 62% of patients of 80 years and older ( P < .001); odds ratio, 15; 95% CI, 9.6-24; P < .001.4 Etiology for rotator cuff pathology varies but rotator cuff tears and tendinopathy are most common in athletes and the elderly.12 It can be the result of a traumatic event or activity-based deterioration such as from excessive use of arms overhead, but some argue that deterioration of these stabilizers is part of the natural aging process given the trend of increased deterioration even in individuals who do not regularly perform overhead activities.2,4 The factors affecting the rotator cuff and subsequent treatment are wide-ranging. The major objectives of this exposition are to describe rotator cuff anatomy, biomechanics, and subacromial impingement; expound upon diagnosis and assessment; and discuss surgical and conservative interventions. -

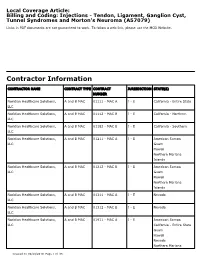

Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma (A57079)

Local Coverage Article: Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma (A57079) Links in PDF documents are not guaranteed to work. To follow a web link, please use the MCD Website. Contractor Information CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01111 - MAC A J - E California - Entire State LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01112 - MAC B J - E California - Northern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01182 - MAC B J - E California - Southern LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01211 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01212 - MAC B J - E American Samoa LLC Guam Hawaii Northern Mariana Islands Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01311 - MAC A J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01312 - MAC B J - E Nevada LLC Noridian Healthcare Solutions, A and B MAC 01911 - MAC A J - E American Samoa LLC California - Entire State Guam Hawaii Nevada Northern Mariana Created on 09/28/2019. Page 1 of 33 CONTRACTOR NAME CONTRACT TYPE CONTRACT JURISDICTION STATE(S) NUMBER Islands Article Information General Information Original Effective Date 10/01/2019 Article ID Revision Effective Date A57079 N/A Article Title Revision Ending Date Billing and Coding: Injections - Tendon, Ligament, N/A Ganglion Cyst, Tunnel Syndromes and Morton's Neuroma Retirement Date N/A Article Type Billing and Coding AMA CPT / ADA CDT / AHA NUBC Copyright Statement CPT codes, descriptions and other data only are copyright 2018 American Medical Association. -

Musculoskeletal Diagnostic Imaging

Musculoskeletal Diagnostic Imaging Vivek Kalia, MD MPH October 02, 2019 Course: Sports Medicine for the Primary Care Physician Department of Radiology University of Michigan @VivekKaliaMD [email protected] Objectives • To review anatomy of joints which commonly present for evaluation in the primary care setting • To review basic clinical features of particular musculoskeletal conditions affecting these joints • To review key imaging features of particular musculoskeletal conditions affecting these joints Outline • Joints – Shoulder – Hip • Rotator Cuff Tendinosis / • Osteoarthritis Tendinitis • (Greater) Trochanteric bursitis • Rotator Cuff Tears • Hip Abductor (Gluteal Tendon) • Adhesive Capsulitis (Frozen Tears Shoulder) • Hamstrings Tendinosis / Tears – Elbow – Knee • Lateral Epicondylitis • Osteoarthritis • Medical Epicondylitis • Popliteal / Baker’s cyst – Hand/Wrist • Meniscus Tear • Rheumatoid Arthritis • Ligament Tear • Osteoarthritis • Cartilage Wear Outline • Joints – Ankle/Foot • Osteoarthritis • Plantar Fasciitis • Spine – Degenerative Disc Disease – Wedge Compression Deformity / Fracture Shoulder Shoulder Rotator Cuff Tendinosis / Tendinitis • Rotator cuff comprised of 4 muscles/tendons: – Supraspinatus – Infraspinatus – Teres minor – Subscapularis • Theory of rotator cuff degeneration / tearing with time: – Degenerative partial-thickness tears allow superior migration of the humeral head in turn causes abrasion of the rotator cuff tendons against the undersurface of the acromion full-thickness tears may progress to -

Enthesitis of the Hands in Psoriatic Arthritis: an Ultrasonographic Perspective

Pictorial essay Med Ultrason 2017, Vol. 19, no. 4, 438-443 DOI: 10.11152/mu-1172 Enthesitis of the hands in psoriatic arthritis: an ultrasonographic perspective Alen Zabotti1, Luca Idolazzi2, Alberto Batticciotto3, Orazio De Lucia4, Carlo Alberto Scirè5, Ilaria Tinazzi6, Annamaria Iagnocco7 1Rheumatology Clinic, Department of Medical and Biological Sciences, University Hospital Santa Maria della Misericordia, Udine, 2Rheumatology Unit, University of Verona, Ospedale Civile Maggiore, Verona, 3Rheumatology Unit, L. Sacco University Hospital, Milan, 4Department of Rheumatology, ASST Centro traumatologico ortopedico G. Pini – CTO, Milan, 5Department of Medical Sciences, Section of Rheumatology, University of Ferrara, Ferrara, 6Unit of Rheumatology, Ospedale Sacro Cuore, Negrar, Verona, 7Dipartimento di Scienze Cliniche e Biologiche, Università degli Studi di Torino, Turin, Italy Abstract Psoriatic arthritis is a systemic inflammatory disease in which enthesitis and dactylitis are two of the main hallmarks of the disease. In the last years, ultrasonography is increasingly playing a key role in the diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis and ultrasonography of the entheses, particularly of the lower limbs, is commonly used to assess patients with that disease. New advancements in ultrasound equipment using high frequencies probes allowed us also to identify and characterize the involve- ment of the entheses of the hand in psoriatic arthritis, confirming the results of the experimental models of the disease and the theory of the sinovial-entheseal complex, even in small joints. Keywords: ultrasonography; psoriatic arthritis; enthesitis; seronegative arthritis; synovio-entheseal complex Introduction fulness to differentiate PsA from Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) [4,5]. The European League Against Rheumatism Psoriatic Arthritis (PsA), usually included in the (EULAR) recommends the use of imaging in diagnosis Spondyloarthritis (SpA) group, can affect different ar- and management of SpA and, in the last years, ultrasound ticular structures, from bone to soft tissues (e.g. -

Enthesopathy and Tendinopathy in Gout: Computed Tomographic Assessment

Ann Rheum Dis 1996;55:921-923 921 CONCISE REPORTS Ann Rheum Dis: first published as 10.1136/ard.55.12.921 on 1 December 1996. Downloaded from Enthesopathy and tendinopathy in gout: computed tomographic assessment Jean-Charles Gerster, Michel Landry, Georges Rappoport, Gilles Rivier, Bertrand Duvoisin, Pierre Schnyder Abstract urate deposits in clinically involved tendons Objective-To establish if computed (Achilles tendon in two patients, patellar tendon tomography (CT) imaging, which has in one patient) was assessed. proved helpful in detecting intra-articular tophi in gout, can also be used to Case reports document gouty enthesopathy and tendin- PATIENT 1 opathy. A 70 year old man was admitted with acute Methods-Three patients with tophaceous arthritis of the left ankle joint. He had been gout and clinical involvement of the suffering from gout for 10 years, and had a his- Achilles tendon (two cases) or patellar tory of excessive alcohol consumption and of tendon (one case) were assessed with CT irregular medication consisting of non- examination and plain radiographs. steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and allopu- Results-In the first two cases, CT images rinol. revealed linear or nodular high attenua- Upon admission, the patient was overweight tion opacities within the substance of the (body mass index 32.8 kg m-', normal < 25), Achilles tendons and their calcaneal and he had an effusion of the left knee, signs of insertion. In case 3, dense linear opacities acute arthritis of the left ankle, and nodules of were seen within the patellar tendon and both Achilles tendons, which were slightly ten- within its tibial insertion. -

The Correlations Between Dimensions of the Normal Tendon And

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN The correlations between dimensions of the normal tendon and tendinopathy changed Achilles tendon in routine magnetic resonance imaging Pawel Szaro 1,2,3* & Khaldun Ghali Gataa2 This comparative study aimed to investigate how tendinopathy-related lesions change correlations in the dimensions of the Achilles tendon. Our experimental group included 74 patients. The mean age was 52.9 ± 10.4 years. The control group included 81 patients with a mean age was 35.2 ± 13.6 years, p < .001. The most signifcant diference in correlation was the thickness of the tendon and the midportion’s width, which was more signifcant in the tendinopathy (r = .49 vs. r = .01, p < .001). The correlation was positive between width and length of the insertion but negative in normal tendons (r = .21 vs. r = − .23, p < .001). The correlation was between the midportions width in tendinopathy and the tendon’s length but negative in the normal tendon (r = .16 vs. r = − .23, p < .001). The average thickness of the midportion in tendinopathy was 11.2 ± 3.3 mm, and 4.9 ± 0.5 mm in the control group, p < .001. The average width of the midportion and insertion was more extensive in the experimental group, 17.2 ± 3.1 mm vs. 14.7 ± 1.8 mm for the midportion and 31.0 ± 3.9 mm vs. 25.7 ± 3.0 mm for insertion, respectively, p < .001. The tendon’s average length was longer in tendinopathy (83.5 ± 19.3 mm vs. 61.5 ± 14.4 mm, p < .001). The dimensions correlations in normal Achilles tendon and tendinopathic tendon difer signifcantly. -

Primary and Secondary Consequences of Rotator Cuff

Hafizur Rahman Department of Mechanical Science and Engineering, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801 Primary and Secondary e-mail: [email protected] Consequences of Rotator Cuff Eric Currier Department of Mechanical Science and Engineering, Injury on Joint Stabilizing University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, IL 61801 Tissues in the Shoulder e-mail: [email protected] Rotator cuff tears (RCTs) are one of the primary causes of shoulder pain and dysfunction Marshall Johnson in the upper extremity accounting over 4.5 million physician visits per year with 250,000 Department of Mechanical Engineering, rotator cuff repairs being performed annually in the U.S. While the tear is often consid- Georgia Institute of Technology, ered an injury to a specific tendon/tendons and consequently treated as such, there are Atlanta, GA 30332 secondary effects of RCTs that may have significant consequences for shoulder function. e-mail: [email protected] Specifically, RCTs have been shown to affect the joint cartilage, bone, the ligaments, as well as the remaining intact tendons of the shoulder joint. Injuries associated with the Rick Goding upper extremities account for the largest percent of workplace injuries. Unfortunately, Department of Orthopaedic, the variable success rate related to RCTs motivates the need for a better understanding Joint Preservation Institute of Iowa, of the biomechanical consequences associated with the shoulder injuries. Understanding West Des Moines, IA 50266 the timing of the injury and the secondary anatomic consequences that are likely to have e-mail: [email protected] occurred are also of great importance in treatment planning because the approach to the treatment algorithm is influenced by the functional and anatomic state of the rotator cuff Amy Wagoner Johnson and the shoulder complex in general. -

Impingement Syndrome and Tears of the Rotator Cuff

Impingement Syndrome and Tears of the Rotator Cuff Dr Keith Holt Impingement is a very common problem in which the tendons of the rotator cuff (predominantly supraspinatus) rub on the underside of the acromion (the bone at the point of the shoulder). This causes pain due to the repeated rubbing of those tendons and it is especially bad with certain positions of the arm. In particular it is difficult to put the arm behind the back and to use it in the elevated position. This makes it difficult to drive, change gears, hang clothes, comb one’s hair, and even to lie on the affected shoulder. The cause of this problem can be: How does the shoulder work? The shoulder, like the hip, is a ball and socket joint (like a tow 1) A muscle imbalance problem due to poor functioning bar). Unlike the hip however, the socket is very small and is of the rotator cuff tendons themselves; thus allowing the not big enough to hold the head of the humerus (the ball) arm to ride up and rub on the acromion, squashing the in place. This gives the joint a large range of motion but, as rotator cuff tendons in the process: or a consequence, it also means that it is potentially unstable. 2) A mechanical problem where the space for the tendon To function normally, muscles on both sides of the joint must is inadequate. One way this can occur is with an injury work together to hold the joint in place during movement. to the tendon itself which causes swelling of that tendon This means that when the deltoid muscle (see diagrams) lifts such that it becomes too large for the space at hand the arm out from the side of the body, the supraspinatus and [primary tendonitis (inflammation of the tendon) with other muscles of the rotator cuff must pull down on the top secondary impingement [rubbing of the tendon on the of the humerus. -

Heel Enthesopathy of Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis

Images in Rheumatology Heel Enthesopathy of Diffuse Idiopathic Skeletal Hyperostosis Resembling Enthesitis of Spondyloarthritis IGNAZIO OLIVIERI, MD, SALVATORE D’ANGELO, MD, Rheumatology Department of Lucania, San Carlo Hospital, Contrada Macchia Romana, 85100 Potenza, Italy; and Madonna delle Grazie Hospital; FRANCESCO BORRACCIA, Researcher, Radiology Department, San Carlo Hospital; ANGELA PADULA, MD, Senior Researcher, Rheumatology Department of Lucania, San Carlo Hospital, and Madonna delle Grazie Hospital, Matera, Italy. Address correspondence to Dr. Olivieri; E-mail: [email protected]. J Rheumatol 2010;37:192–3; doi.10.3899/jrheum.090514 Diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis (DISH) and anky- tendons, resembling the typical fusiform soft tissue swelling losing spondylitis (AS) are 2 clearly different disease enti- of Achilles enthesitis of spondyloarthritis5 (Figure 1). ties having in common the involvement of the axial skeleton However, palpation of the region did not reveal any inflam- and the peripheral entheses1,2. Both diseases produce bone matory findings of enthesitis but did reveal bone prolifera- proliferation in the spine and at the extraspinal entheseal tion due to large spurs, a condition confirmed by radio- sites in the later phases of their course. Although the aspects graphs (Figure 2). A sacroiliac joint computed tomography of the bone proliferations of the 2 diseases are dissimilar, (CT) scan showed the normal aspect of joint space and bony confusion of radiographic differential diagnosis between the margins together with the presence of capsular ossifications 2 diseases exists, partly as a consequence of a lack of aware- (Figure 3). ness of their respective characteristic features2,3. It has been pointed out that the differential diagnosis between DISH and REFERENCES longstanding advanced AS is not limited to the radiologic 1.