Report from the Academy Task Force on Central Presbycusis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Age-Related Hearing Loss

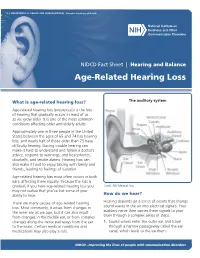

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES ∙ National Institutes of Health NIDCD Fact Sheet | Hearing and Balance Age-Related Hearing Loss What is age-related hearing loss? The auditory system Age-related hearing loss (presbycusis) is the loss of hearing that gradually occurs in most of us as we grow older. It is one of the most common conditions affecting older and elderly adults. Approximately one in three people in the United States between the ages of 65 and 74 has hearing loss, and nearly half of those older than 75 have difficulty hearing. Having trouble hearing can make it hard to understand and follow a doctor’s advice, respond to warnings, and hear phones, doorbells, and smoke alarms. Hearing loss can also make it hard to enjoy talking with family and friends, leading to feelings of isolation. Age-related hearing loss most often occurs in both ears, affecting them equally. Because the loss is gradual, if you have age-related hearing loss you Credit: NIH Medical Arts may not realize that you’ve lost some of your ability to hear. How do we hear? There are many causes of age-related hearing Hearing depends on a series of events that change loss. Most commonly, it arises from changes in sound waves in the air into electrical signals. Your the inner ear as we age, but it can also result auditory nerve then carries these signals to your from changes in the middle ear, or from complex brain through a complex series of steps. changes along the nerve pathways from the ear 1. -

PRESBYCUSIS Diagnosis and Treatment

Hear the FACTS about PRESBYCUSIS Diagnosis and Treatment NORMAL HEARING What is Presbycusis? FREQUENCY (in Hertz) . A gradual reduction in hearing as we get older, typically affecting both 250 500 1000 2000 4000 8000 -10 ears equally. 0 X 10 X X Common in men and women, with men typically having greater X •X . 20 • •X • • • 30 hearing loss than women of the same age. 40 Typically a greater hearing loss for high frequency sounds than for low 50 . (in dBHL) 60 INTENSITY frequency sounds. 70 80 A treatable condition that can benefit greatly from technological 90 . advances in various amplification or hearing assistance devices, along 100 • Right Ear 110 X Left Ear with counseling on effective communication strategies. PRESBYCUSIS HEARING LOSS What causes Presbycusis? FREQUENCY (in Hertz) . Family history or hereditary factors. 250 500 1000 2000 4000 8000 -10 Changes in the inner ear blood supply related to heart disease, 0 . 10 •X diabetes, high blood pressure and smoking. 20 •X 30 •X A loss of sound sensitivity from cumulative exposure to loud sounds. 40 •X . 50 (in dBHL) 60 INTENSITY X 70 • Symptoms: X 80 • •X 90 . Frequently asking people to repeat what they say, especially in 100 Right Ear “difficult listening places”. 110 X Left Ear . Ability to hear lower-pitched men's voices easier than higher-pitched NORMAL INNER EAR PRESBYCUSIC INNER EAR women’s or children’s voices. People complaining that the TV is being played too loud. Tinnitus, also known as “head noise”, which produces buzzing or ringing sounds in the ear. Diagnosis: . Talk honestly with your Hearing Healthcare Provider about daily hearing problems. -

A Molecular and Genetic Analysis of Otosclerosis

A molecular and genetic analysis of otosclerosis Joanna Lauren Ziff Submitted for the degree of PhD University College London January 2014 1 Declaration I, Joanna Ziff, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. Where work has been conducted by other members of our laboratory, this has been indicated by an appropriate reference. 2 Abstract Otosclerosis is a common form of conductive hearing loss. It is characterised by abnormal bone remodelling within the otic capsule, leading to formation of sclerotic lesions of the temporal bone. Encroachment of these lesions on to the footplate of the stapes in the middle ear leads to stapes fixation and subsequent conductive hearing loss. The hereditary nature of otosclerosis has long been recognised due to its recurrence within families, but its genetic aetiology is yet to be characterised. Although many familial linkage studies and candidate gene association studies to investigate the genetic nature of otosclerosis have been performed in recent years, progress in identifying disease causing genes has been slow. This is largely due to the highly heterogeneous nature of this condition. The research presented in this thesis examines the molecular and genetic basis of otosclerosis using two next generation sequencing technologies; RNA-sequencing and Whole Exome Sequencing. RNA–sequencing has provided human stapes transcriptomes for healthy and diseased stapes, and in combination with pathway analysis has helped identify genes and molecular processes dysregulated in otosclerotic tissue. Whole Exome Sequencing has been employed to investigate rare variants that segregate with otosclerosis in affected families, and has been followed by a variant filtering strategy, which has prioritised genes found to be dysregulated during RNA-sequencing. -

Alzheimer's Disease, Hearing Loss, Presbycusis, Tinnitus, Older Adults

International Journal of Psychology and Behavioral Sciences 2018, 8(5): 77-80 DOI: 10.5923/j.ijpbs.20180805.01 Alzheimer’s Disease and Hearing Loss among Older Adults: A Literature Review Fereshteh Bagheri1, Vahidreza Borhaninejad2, Vahid Rashedi3,4,* 1Department of Audiology, School of Rehabilitation Sciences, Babol University of Medical Sciences, Mazandaran, Iran 2Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Institute for Futures Studies in Health, Kerman University of Medical Sciences Kerman, Iran 3School of Behavioural Sciences and Mental Health (Tehran Institute of Psychiatry), Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran 4Iranian Research Centre on Aging, University of Social Welfare and Rehabilitation Sciences, Tehran, Iran Abstract Older adults with hearing loss are more likely to develop Alzheimer's disease (AD) or dementia compared to those with normal hearing. Hearing loss can be consecutive to presbycusis and/or central auditory dysfunction. The current study reviewed the literature concerning the relationship between hearing loss and AD among older adults. Articles included in this review were identified through a search of the databases PubMed, Medline, Scopus, Google Scholar, and Scientific Information Database (SID) using the search terms Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, presbycusis, hearing loss, and hearing impairment. The literature search was restricted to the years 1989 to 2018 and to articles published in the English language. Of 54 primary articles, 38 potentially eligible articles were reviewed. Although cognitive decline has been shown to be slowed by the use of hearing aids in older adults, a few studies have investigated the effects of other factors such as presbycusis-related tinnitus and length of use of hearing aids by older adults. -

Differential Diagnosis and Treatment of Hearing Loss JON E

Differential Diagnosis and Treatment of Hearing Loss JON E. ISAACSON, M.D., and NEIL M. VORA, M.D., Milton S. Hershey Medical Center, Hershey, Pennsylvania Hearing loss is a common problem that can occur at any age and makes verbal communication difficult. The ear is divided anatomically into three sections (external, middle, and inner), and pathology contributing to hearing loss may strike one or more sections. Hearing loss can be cat- egorized as conductive, sensorineural, or both. Leading causes of conductive hearing loss include cerumen impaction, otitis media, and otosclerosis. Leading causes of sensorineural hear- ing loss include inherited disorders, noise exposure, and presbycusis. An understanding of the indications for medical management, surgical treatment, and amplification can help the family physician provide more effective care for these patients. (Am Fam Physician 2003;68:1125-32. Copyright© 2003 American Academy of Family Physicians) ore than 28 million Amer- tive, the sound will be heard best in the icans have some degree of affected ear. If the loss is sensorineural, the hearing impairment. The sound will be heard best in the normal ear. differential diagnosis of The sound remains midline in patients with hearing loss can be sim- normal hearing. Mplified by considering the three major cate- The Rinne test compares air conduction gories of loss. Conductive hearing loss occurs with bone conduction. The tuning fork is when sound conduction is impeded through struck softly and placed on the mastoid bone the external ear, the middle ear, or both. Sen- (bone conduction). When the patient no sorineural hearing loss occurs when there is a longer can hear the sound, the tuning fork is problem within the cochlea or the neural placed adjacent to the ear canal (air conduc- pathway to the auditory cortex. -

Central Auditory Processing Deficits in the Elderly

American Journal of www.biomedgrid.com Biomedical Science & Research ISSN: 2642-1747 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Review Article Copyright@ Lilian Felipe Central Auditory Processing Deficits in the Elderly Lilian Felipe* Speech and Hearing Department, Lamar University, USA *Corresponding author: Lilian Felipe, Speech and Hearing Department, Lamar University, USA To Cite This Article: Lilian Felipe. Central Auditory Processing Deficits in the Elderly. Am J Biomed Sci & Res. 2019 - 3(2). AJBSR.MS.ID.000654. DOI: 10.34297/AJBSR.2019.03.000654 Received: March 06, 2019 | Published: May 28, 2019 Abstract to multiple speakers, or understanding complex messages. When the listening situation is complex or challenging the person expands additional listeningElderly effort, persons which with can andlead without to fatigue, hearing reduced loss attention, experience and difficulty forgetfulness. listening Beyond to speech the age-related in background effects noise, on hearing, following known rapid as speech, presbycusis, attending the central auditory system suffers decline in processing abilities with memory and attention. This common occurrence for the aging brain to experience speech in noise, dichotic processing which is attending to stimuli in one/both/alternating ears, and temporal processing which is attending to rapid changessome decline in stimuli. in functioning, Research isshows known that as, engaging “central presbycusis”.in cognitively Specifically demanding related activities to the like auditory reading, system, learning, the playing brain declines games, playing in its ability chess, to speaking listen to another language, being physically active, engaging in social activities, and playing music can delay and/or reduce cognitive decline and dementia. ThisKeywords: paper will further elaborate on the effects of central auditory processing deficits resulting from central presbycusis in the elderly. -

Analysis of Chronic Tinnitus in Noise-Induced Hearing Loss and Presbycusis

Journal of Clinical Medicine Article Analysis of Chronic Tinnitus in Noise-Induced Hearing Loss and Presbycusis Hee Jin Kang 1, Dae Woong Kang 1, Sung Su Kim 2, Tong In Oh 3 , Sang Hoon Kim 1 and Seung Geun Yeo 1,* 1 Department of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery, School of Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul 02447, Korea; [email protected] (H.J.K.); [email protected] (D.W.K.); [email protected] (S.H.K.) 2 Medical Research Center for Bioreaction to Reactive Oxygen Species and Biomedical Science Institute, School of Medicine, Graduate School, Kyung Hee University, Seoul 02447, Korea; [email protected] 3 Department of Biomedical Engineering, College of Medicine, Kyung Hee University, Seoul 02447, Korea; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +82-2-958-8980; Fax: +82-2-958-8470 Abstract: Introduction: The most frequent causes of tinnitus associated with hearing loss are noise- induced hearing loss and presbycusis. The mechanism of tinnitus is not yet clear, although several hypotheses have been suggested. Therefore, we aimed to analyze characteristics of chronic tinnitus between noise-induced hearing loss and presbycusis. Materials and Methods: This paper is a retrospective chart review and outpatient clinic-based study of 248 patients with chronic tinnitus from 2015 to 2020 with noise-induced or presbycusis. Pure tone audiometry (PTA), auditory brainstem response (ABR), distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAE), transient evoked otoacoustic emissions (TEOAE), and tinnitograms were conducted. Results: PTA showed that hearing thresholds at all frequencies were higher in patients with noise-induced hearing loss than the presbycusis group. Citation: Kang, H.J.; Kang, D.W.; ABR tests showed that patients with presbycusis had longer wave I and III latencies (p < 0.05 each) Kim, S.S.; Oh, T.I.; Kim, S.H.; Yeo, S.G. -

Clinical and Audiometric Features of Presbycusis in Nigerians

Clinical and audiometric features of presbycusis in Nigerians *Sogebi OA11, Olusoga-Peters OO2, Oluwapelumi O2 1. Department of Surgery, College of Health Sciences, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Sagamu. Nigeria. 2. Department of Ear, Nose and Throat, Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital, Sagamu, Nigeria Abstract Background: Presbycusis is the most common sensory impairment associated with ageing and it presents with variability of symptoms. Physicians need to recognize early clinical and audiometric signs of presbycusis in order to render adequate and quality care to patients and reduce associated morbidities. Objective: To characterize the clinical modes of presentation and the typical audiometric tracings among patients with presbycusis. Methods: This descriptive, prospective hospital-based study was conducted in the Ear, Nose and Throat (ENT) clinic of Olabisi Onabanjo University Teaching Hospital, (OOUTH) Sagamu, Nigeria. Patients with clinical diagnosis of presbycusis confirmed with bilateral sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) on diagnostic audiometry were administered with questionnaires. Information obtained was analyzed using SPSS statistical package version 17.0 and presented in descriptive forms as percentages, means and graphs. Results: Sixty-nine patients were diagnosed with presbycusis (M:F =1.6:1). Modal age group was 71-80 years. Hearing loss 88.4%, tinnitus 79.7% and vertigo 33.3% were the major symptoms on presentation. The average duration of symptoms before presentation was 2.6 years. There was positive history of ototoxic drugs usage in 24.6 %, family history in 11.6 %, hypertension in 34.8% and osteoarthritis in 13.0%. The most common type of audiometric pattern was strial. Hearing losses increased with age both at the speech and at the higher frequencies of sounds. -

Cochlear Neuropathy in Human Presbycusis: Confocal Analysis of Hidden Hearing Loss in Post-Mortem Tissue

Hearing Research 327 (2015) 78e88 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Hearing Research journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/heares Research paper Cochlear neuropathy in human presbycusis: Confocal analysis of hidden hearing loss in post-mortem tissue Lucas M. Viana d, Jennifer T. O'Malley c, Barbara J. Burgess c, Dianne D. Jones c, Carlos A.C.P. Oliveira d, Felipe Santos a, c, Saumil N. Merchant a, b, c, Leslie D. Liberman b, c, * M. Charles Liberman a, b, c, a Department of Otology and Laryngology, Harvard Medical School, Boston MA, USA b Eaton-Peabody Laboratories, Massachusetts Eye & Ear Infirmary, Boston MA, USA c Department of Otolaryngology, Massachusetts Eye and Ear, Boston MA, USA d Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Brasilia, Brasilia, Distrito Federal, Brazil article info abstract Article history: Recent animal work has suggested that cochlear synapses are more vulnerable than hair cells in both Received 25 February 2015 noise-induced and age-related hearing loss. This synaptopathy is invisible in conventional histopatho- Received in revised form logical analysis, because cochlear nerve cell bodies in the spiral ganglion survive for years, and synaptic 3 April 2015 analysis requires special immunostaining or serial-section electron microscopy. Here, we show that the Accepted 28 April 2015 same quadruple-immunostaining protocols that allow synaptic counts, hair cell counts, neuronal counts Available online 19 May 2015 and differentiation of afferent and efferent fibers in mouse can be applied to human temporal bones, when harvested within 9 h post-mortem and prepared as dissected whole mounts of the sensory epithelium and osseous spiral lamina. -

Management of Tinnitus in Patients with Presbycusis

International Tinnitus Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2, 175–178 (2006) Management of Tinnitus in Patients with Presbycusis Olaf Zagólski Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Diagnostic and Therapeutic Medical Center, Medicina, Kraków, Poland Abstract: Sensorineural hearing loss in elderly patients (presbycusis) relatively often coex- ists with annoying tinnitus (termed presbytinnitus [PT] by Claussen). The purpose of this study was to verify the conditions of improvement in patients treated for PT. We fitted with hearing aids 33 PT patients (ages 60–89 years) and questioned them about subjective hearing results. Assessment tools included comprehensive audiology and a subjective self-assessment survey of tinnitus characteristics. All patients had very good tolerance of the hearing aids; 28 reported that they had considerable reduction in PT intensity. Fitting PT patients with hearing aids is usually effective. In patients with unilateral sensorineural hearing loss and tinnitus, fit- ting the impaired ear is sufficient. Individuals with bilateral complaints require bilateral fitting. Effectiveness of fitting in the affected group of patients depended on speech discrimination scores before fitting. The improvement scores were higher in patients with more aggravated symptoms and did not depend on history of prolonged exposure to excessive noise. Key Words: elderly patients; presbycusis; presbytinnitus; tinnitus ensorineural hearing loss in elderly patients— both) [7]. PT usually occurs in the poorer hearing ear, presbycusis (PC)—results from atrophy of hair and PT individuals have a significant reduction in com- S cells in the organ of Corti, degeneration of nerve munication skills [7]. fibers in the cochlear ganglion and the cochlear nuclei, The two types of PT are type I, the minority group impaired blood supply of the spiral ligament and the (in which PT develops as a primary initial complaint in vascular stripe, and atrophy of the spiral ligament and association with a preexisting high-tone sensorineural rupture of the cochlear duct [1]. -

Ultrarare Heterozygous Pathogenic Variants of Genes Causing Dominant Forms of Early-Onset Deafness Underlie Severe Presbycusis

Ultrarare heterozygous pathogenic variants of genes causing dominant forms of early-onset deafness underlie severe presbycusis Sophie Bouchera,b,c,d, Fabienne Wong Jun Taia, Sedigheh Delmaghania, Andrea Lellia, Amrit Singh-Estivaleta,b, Typhaine Duponta, Magali Niasme-Grarea,e, Vincent Michela, Nicolas Wolfff, Amel Bahloula, Yosra Bouyacouba, Didier Bouccarag, Bernard Fraysseh, Olivier Deguineh, Lionel Colleti, Hung Thai-Vana,j,k, Eugen Ionescuj, Jean-Louis Kemenyl, Fabrice Giraudetm,n, Jean-Pierre Lavieilleo, Arnaud Devèzeo, Anne-Laure Roudevitch-Pujolp, Christophe Vincentq, Christian Renardr, Valérie Franco-Vidals, Claire Thibult-Apts, Vincent Darrouzets, Eric Bizaguett, Arnaud Coezt,u,v, Hugues Aschardw, Nicolas Michalskia, Gaëlle M. Lefevrea, Anne Auboisp, Paul Avana,m,n,x,1, Crystel Bonneta,b,1, and Christine Petita,y,1,2 aInstitut de l’Audition, Institut Pasteur, INSERM, 75012 Paris, France; bComplexité du Vivant, Sorbonne Universités, Université Pierre et Marie Curie, Université Paris 06, 75005 Paris, France; cCentre Hospitalier Universitaire, Service d’Oto-Rhino-Laryngologie et Chirurgie Cervico-Faciale, 49100 Angers, France; dFaculté de Médecine, Unité de Formation et de Recherche Santé, Université d’Angers, 49100 Angers, France; eService de Biochimie et Biologie Moléculaire, Hôpital d’Enfants Armand-Trousseau, Assistance Publique-Hôpitaux de Paris (AP-HP), 75012 Paris, France; fUnité Récepteurs-Canaux, Institut Pasteur, 75015 Paris, France; gHôpital Beaujon, Hôpitaux Universitaires Paris Nord val-de-Seine, AP-HP, 92110 Clichy, -

Comprehensive Management of Presbycusis: Central and Peripheral Kourosh Parham University of Connecticut School of Medicine and Dentistry

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OpenCommons at University of Connecticut University of Connecticut OpenCommons@UConn Articles - Patient Care Patient Care 4-2013 Comprehensive management of presbycusis: Central and peripheral Kourosh Parham University of Connecticut School of Medicine and Dentistry Follow this and additional works at: https://opencommons.uconn.edu/pcare_articles Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Parham, Kourosh, "Comprehensive management of presbycusis: Central and peripheral" (2013). Articles - Patient Care. 46. https://opencommons.uconn.edu/pcare_articles/46 NIH Public Access Author Manuscript Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2013 December 12. NIH-PA Author ManuscriptPublished NIH-PA Author Manuscript in final edited NIH-PA Author Manuscript form as: Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013 April ; 148(4): . doi:10.1177/0194599813477596. Comprehensive management of presbycusis: Central and peripheral Kourosh Parham, MD, PhD1, Frank R. Lin, MD, PhD2,3, Daniel H. Coelho, MD4, Robert T. Sataloff, MD5, and George A. Gates, MD6 1Department of Surgery, Division of Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery, University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington, Connecticut 2Departments of Otolaryngology-Head & Neck Surgery and Epidemiology, Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, Maryland 3Center on Aging and Health, Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore,