Dissertation (PDF)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PULL TOGETHER Newsletter of the Naval Historical Foundation OUTREACH!

Preservation, Education, and Commemoration Vol. 54, No. 2 Spring 2015 PULL TOGETHER Newsletter of the Naval Historical Foundation OUTREACH! Happy 100th U.S. Navy Reserve! Also in the issue: Welcome Aboard Rear Admiral Sam Cox, pp. 3-5; Washington Awards Dinner, pp. 6-7; Partner Profi le: Pritzker Military Museum and Library, p. 9; News from the Naval Historical Foundation, p. 10; Annual Report, pp. 11-14. Message From the Chairman The theme of this edition of Pull Together is the growing number of outreach activities that aim to educate the general public on aspects of our great naval heritage. An alliance of partners is helping to make these activities happen. Again in 2015 we offer many opportunities for members to discuss, share, and be a part of naval history. On April 15, the NHF is partnering for two member events. Once again at the Washington Navy Yard, we are joining with the Naval Submarine League to cohost the annual Submarine History Seminar, which will focus on the submarine-launched ballistic missile partnership this nation has maintained with Great Britain for a half a century. Meanwhile at Fraunce’s Tavern in New York, we will join with the local Navy League Council to honor Commo. Dudley W. Knox medal recipient Craig Symonds who will receive the John Barry Book Prize for his publication of Operation Neptune. A week later, on April 23, we gather with the National Maritime Historical Society for our joint Washington Awards dinner at the National Press Club where I will join with retired Coast Guard Commandant Robert Papp to present CNO Adm. -

BLT 2/1 Returns from 11Th MEU WESTPAC Marines and Japanese Soldiers Kick Off Iron Fist 2015 Blue Diamond

BLT 2/1 returns from 11th MEU WESTPAC MARINE CORPS BASE CAMP PENDLETON, Calif. - Marines with the Battalion Landing Team 2nd Battalion, 1st Marine Regiment, 11th Marine Expeditionary Unit returned to Camp Pendleton, California, Feb 24. The 11th MEU completed a 7- month deployment to the U.S. 5th Fleet and 7th Fleet areas of operation. The 11th MEU, along with the Makin Island Amphibious Ready Group, deployed July 25 and participated in multiple exercises with regional host nations in both U.S. Pacific Command and U.S. Central Command, where the MEU served as a reserve force supporting contingency operations while also supporting Operation Inherent Resolve. Marines and Japanese soldiers kick off Iron Fist 2015 MARINE CORPS BASE CAMP PENDLETON, Calif. – U.S. Marines with the 13th Marine Expeditionary Unit stood alongside soldiers of the Japan Ground Self-Defense Force’s Western Army Infantry Regiment to kick off Exercise Iron Fist 2015 during an opening ceremony aboard Camp Pendleton, Calif., Jan. 26, 2015. Exercise Iron Fist 2015 marks the 10th anniversary of the amphibious training partnership with the Japan Ground Self- Defense Force to enhance United States Marine Corps and JGSDF interoperability, develop the Self-Defense Force’s amphibious capabilities and build military-to-military relationships between the two forces. Click here to read more Blue Diamond: A 74-year legacy MARINE CORPS BASE CAMP PENDLETON, Calif. - Marines, sailors and veterans of the 1st Marine Division honored the division’s 74th anniversary during a battle colors rededication ceremony aboard Camp Pendleton, California, Jan. 22, 2015. Major Gen. Lawrence D. -

December 1950

7TH MARINE REGIMENT - HISTORICAL DIARY - AUGUST 1950 - DECEMBER 1950 Korean War Korean War Project Record: USMC-2281 CD: 22 United States Marine Corps History Division Quantico, Virginia Records: United States Marine Corps Unit Name: 1st Marine Division Records Group: RG 127 Depository: National Archives and Records Administration Location: College Park, Maryland Editor: Hal Barker Korean War Project P.O. Box 180190 Dallas, TX 75218-0190 http://www.koreanwar.org Korean War Project USMC-08300001 DECLASSIFIED - I 0680/946 Al2 Ser _Q.056-5.t FEB 21 1951 FIRST ENDORSEMENT on CG, lstMarDiv 1 tr to CMC, aer 0021-51 of 8 Feb 1961 From: Commanding General, Fleet Marine Force, Pacific To: Commandant of the Marine Corps SubJ: Historical Diaries, 7th Marines; period August - November 1950 1. Forwarded. .1.0()()';'8 c/e~~.... J. C. BURGER COLONEL, U. S. MARINE CORPS Copy to: CHIEF OF STAFF ' CG, lstMarDi v • ....... - DECLASSIFIED Korean War Project USMC-08300002 DECLASSIFIED pi;~ ~-. :._- ·-:::::~~--"'""'~--:;;·;-:p;...ii.,-:-_*jil"'·--....-=- .... ----!,.o.l-.,--~-. I'll 41-1/ldJ Ser 058-51 28 "ebru<>ry 19 51 FIRST ::::nc·::!S:'].!El!T on 7thl4ar Historical Diary for December 1950, ltr ser 505 of 17 Feb 1951 From: Comr.~anding Gener:cl, lst Marine Division, FMF To: Commsnde_nt of the Marine Corps Yia: Comm<e.n•3.ing Generr\l, Fleet Marine Force, Pacific Saoj: His toricc.l DiarJ' for Decenber 1950 2. Tl1e secu:·ity classification o:' this e:ldorsement is rell!ovecl ,.r~1ea tetc.ched :"rom the bEtsic le~ter. ~~- H. S. \;'.~SETH De~>ut;r Chief of Staff far Administration :'.,.• '•. -

US Navy Mine Warfare Champion

Naval War College Review Volume 68 Article 8 Number 2 Spring 2015 Wanted: U.S. Navy Mine Warfare Champion Scott .C Truver Follow this and additional works at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review Recommended Citation Truver, Scott .C (2015) "Wanted: U.S. Navy Mine Warfare Champion," Naval War College Review: Vol. 68 : No. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://digital-commons.usnwc.edu/nwc-review/vol68/iss2/8 This Additional Writing is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Naval War College Review by an authorized editor of U.S. Naval War College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Truver: Wanted: U.S. Navy Mine Warfare Champion COMMENTARY WANTED U.S. NAVY MINE WARFARE CHAMPION Scott C. Truver Successfully implementing innovation within a bureaucracy ultimately requires a champion to navigate the inherently political processes of securing sponsorship and resourcing. This is just as important to the very small as to the very large programs, particularly during periods of fiscal austerity. “It’s fragmented,” com- mented retired rear admiral Paul Ryan, former commander of the U.S. Navy’s Mine Warfare Command, in April 2014. “There is no single champion for mine warfare.”1 This lack of support presents challenges for the U.S. Navy and the nation, as the service struggles to articulate, and to muster the necessary backing for, mine warfare (MIW) strategies, programs, capabilities, and capacities. The task of confronting these challenges is complicated by the fact that MIW comprises not only mine-countermeasures (MCM—that is, minesweeping and mine hunt- ing) systems and platforms but also mines that can be employed to defeat our adversaries’ naval strategies and forces. -

CAMP PENDLETON HISTORY Early History Spanish Explorer Don

CAMP PENDLETON HISTORY Early History Spanish explorer Don Gasper de Portola first scouted the area where Camp Pendleton is located in 1769. He named the Santa Margarita Valley in honor of St. Margaret of Antioch, after sighting it July 20, St. Margaret's Day. The Spanish land grants, the Rancho Santa Margarita Y Las Flores Y San Onofre came in existence. Custody of these lands was originally held by the Mission San Luis Rey de Francia, located southeast of Pendleton, and eventually came into the private ownership of Pio Pico and his brother Andre, in 1841. Pio Pico was a lavish entertainer and a politician who later became the last governor of Alto California. By contrast, his brother Andre, took the business of taming the new land more seriously and protecting it from the aggressive forces, namely the "Americanos." While Andre was fighting the Americans, Pio was busily engaged in entertaining guests, political maneuvering and gambling. His continual extravagances soon forced him to borrow funds from loan sharks. A dashing businesslike Englishman, John Forster, who has recently arrived in the sleepy little town of Los Angeles, entered the picture, wooing and winning the hand of Ysidora Pico, the sister of the rancho brothers. Just as the land-grubbers were about to foreclose on the ranch, young Forster stepped forward and offered to pick up the tab from Pio. He assumed the title Don Juan Forster and, as such, turned the rancho into a profitable business. When Forster died in 1882, James Flood of San Francisco purchased the rancho for $450,000. -

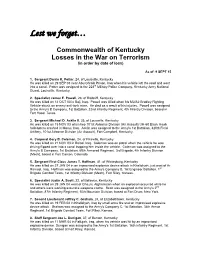

Lest We Forget…

Lest we forget… Commonwealth of Kentucky Losses in the War on Terrorism (in order by date of loss) As of: 9 SEPT 15 1. Sergeant Darrin K. Potter, 24, of Louisville, Kentucky He was killed on 29 SEP 03 near Abu Ghraib Prison, Iraq when his vehicle left the road and went into a canal. Potter was assigned to the 223rd Military Police Company, Kentucky Army National Guard, Louisville, Kentucky. 2. Specialist James E. Powell, 26, of Radcliff, Kentucky He was killed on 12 OCT 03 in Baji, Iraq. Powell was killed when his M2/A2 Bradley Fighting Vehicle struck an enemy anti-tank mine. He died as a result of his injuries. Powell was assigned to the Army's B Company, 1st Battalion, 22nd Infantry Regiment, 4th Infantry Division, based in Fort Hood, Texas. 3. Sergeant Michael D. Acklin II, 25, of Louisville, Kentucky He was killed on 15 NOV 03 when two 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters crashed in Mosul, Iraq. Acklin was assigned to the Army's 1st Battalion, 320th Field Artillery, 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault), Fort Campbell, Kentucky. 4. Corporal Gary B. Coleman, 24, of Pikeville, Kentucky He was killed on 21 NOV 03 in Balad, Iraq. Coleman was on patrol when the vehicle he was driving flipped over into a canal trapping him inside the vehicle. Coleman was assigned to the Army's B Company, 1st Battalion, 68th Armored Regiment, 3rd Brigade, 4th Infantry Division (Mech), based in Fort Carson, Colorado. 5. Sergeant First Class James T. Hoffman, 41, of Whitesburg, Kentucky He was killed on 27 JAN 04 in an improvised explosive device attack in Khalidiyah, just east of Ar Ramadi, Iraq. -

NAVMC 2922 Unit Awards Manual (PDF)

DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY HEADQUARTERS UNITED STATES MARINE CORPS 2008 ELLIOT ROAD QUANTICO, VIRGINIA 22134-5030 IH REPLY REFER TO: NAVMC 2 922 MMMA JAN 1 C IB# FOREWORD 1. Purpose. To publish a listing of all unit awards that have been presented to Marine Corps units since the beginning of World War II. 2. Cancellation. NAVMC 2922 of 17 October 2011. 3. Information. This NAVMC provides a ready reference for commanders in determining awards to which their units are entitled for specific periods of time, facilitating the updating of individual records, and accommodating requests by Marines regarding their eligibility to wear appropriate unit award ribbon bars. a . Presidential Unit Citation (PUC), Navy Unit Citation (NUC), Meritorious Unit Citation (MUC) : (1) All personnel permanently assigned and participated in the action(s) for which the unit was cited. (2) Transient, and temporary duty are normally ineligible. Exceptions may be made for individuals temporarily attached to the cited unit to provide direct support through the particular skills they posses. Recommendation must specifically mention that such personnel are recommended for participation in the award and include certification from the cited unit's commanding officer that individual{s) made a direct, recognizable contribution to the performance of the services that qualified the unit for the award. Authorized for participation by the awarding authority upon approval of the award. (3) Reserve personnel and Individual Augmentees <IAs) assigned to a unit are eligible to receive unit awards and should be specifically considered by commanding officers for inclusion as appropriate, based on the contributory service provided, (4) Civilian personnel, when specifically authorized, may wear the appropriate lapel device {point up). -

NAVAL ENERGY FORUM Creating Spartan Energy Warriors: Our Competitive Advantage

PROMOTING NATIONAL SECURITY SINCE 1919 NAVAL ENERGY FORUM Creating Spartan Energy Warriors: Our Competitive Advantage FORUM HIGHLIGHTS: u Keynote Addresses by Secretary of the Navy Ray Mabus, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Jonathan Greenert, Admiral John C. Harvey, and other Distinguished Guests u Presentations on importance of culture change, successes/challenges for our fleet and shore infrastructure, investments in alternative fuels, information systems, energy efficient acquisition, and game changing solutions u Special remarks by Mr. Jim Hornfischer, New York Times bestselling author OCTOBER 13-14, 2011 RONALD REAGAN BUILDING & ITC u WASHINGTON, DC WWW.GREENFLEET.DODLIVE.MIL/ENERGY WWW.NDIA.ORG/MEETINGS/2600 A WELCOME MESSAGE Welcome to the 2011 Naval Energy Forum. wars, deterring aggression, and maintaining freedom of the seas. That Since I announced the Navy’s energy goals is why avoiding these fuel price spikes and elevations is essential to the at this forum two years ago, we have Navy’s core mission, and why developing alternative fuels is a priority. We made remarkable progress in our efforts have already seen a return on our investments in more efficient energy to achieve greater energy security for the use. Last year, we launched the first hybrid ship in the Navy, the USS Navy and the nation. I am committed to Makin Island. In its maiden voyage, the Makin Island saved almost $2 positioning our Naval forces for tomorrow’s million in fuel costs. Over the lifetime of the ship, we can save $250 challenges, and changing the way the million at last year’s fuel prices. Department of the Navy uses, produces, and acquires energy is one of our greatest We also continue to make progress in our efforts to test and certify all challenges because it is also one of our of our aircraft and ships on drop-in biofuels. -

George's Last Stand: Strategic Decisions and Their Tactical Consequences in the Final Days of the Korean War

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Masters Theses Graduate School 5-2012 George's Last Stand: Strategic Decisions and Their Tactical Consequences in the Final Days of the Korean War Joseph William Easterling [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes Part of the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Easterling, Joseph William, "George's Last Stand: Strategic Decisions and Their Tactical Consequences in the Final Days of the Korean War. " Master's Thesis, University of Tennessee, 2012. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_gradthes/1149 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. To the Graduate Council: I am submitting herewith a thesis written by Joseph William Easterling entitled "George's Last Stand: Strategic Decisions and Their Tactical Consequences in the Final Days of the Korean War." I have examined the final electronic copy of this thesis for form and content and recommend that it be accepted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree of Master of Arts, with a major in History. G. Kurt Piehler, Major Professor We have read this thesis and recommend its acceptance: Stephen Ash, Monica Black Accepted for the Council: Carolyn R. Hodges Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School (Original signatures are on file with official studentecor r ds.) George’s Last Stand: Strategic Decisions and Their Tactical Consequences in the Final Days of the Korean War A Thesis Presented for the Master of Arts Degree The University of Tennessee, Knoxville Joseph William Easterling May 2012 Copyright © 2012 by Joseph W. -

Copyrighted Material

Index Page numbers in italics refer to illustrations. Albany, New York, 139 “Back the Attack” slogan, 135, 137, Alexander, Joe, 183–191, 193, 198, 143, 147 199–201, 215 Baldwin, Raymond E., 138 Allbritton, Louise, 84, 143 Basilone, Alphonse (brother), 87 Alvino, Lawrence “Cookie Hound,” 210 Basilone, Angelo (brother), 219–220 American Civil War, 16 Basilone, Carlo (brother), 150 American Cyanamid, 116, 144 Basilone, Dolores (sister) American Revolution, 15–16 on brother’s death, 220–221 Amtrac 3C27, 194–195, 199 death of, 95 Andrews Sisters, 8 views on Ed Sullivan, 152 ANZAC, 20 Basilone, Donald (brother), 74, 95, 96, Aquilina, Robert V., 48, 53, 82, 215, 141, 145, 221 227, 229 Basilone, Dora (Bengivenga) (mother) Arlington National Cemetery, biographical information, 79 89–90, 218 notifi ed of son’s death, 220, Arnold, Laurence, 228–229 223–226 Australia, 20 at son’s burial, 142, 218 Australian casualties at Basilone, George (brother), 76, 149, Guadalcanal, 26 161, 170, 176–177 Basilone in, 3, 60–61, 62–69, Battle of Iwo Jima and, 214, 221 70–76,COPYRIGHTED 123, 129, 156, 194, 230 concerns MATERIAL for brother’s safety, Congressional Medal of Honor 194, 203 ceremony held in, 57, 70–74, 126, notifi ed of brother’s death, 219 127, 156, 230 Basilone, Lena Riggi (wife) 1st Battalion, 7th Marine Regiment Basilone family and, 94, 220, 225 in, 60–61, 62–69 courtship with Basilone, 164–165, Japan’s World War II threat to, 20, 169–171 66–67, 75 death of, 226 245 bbindex.inddindex.indd 224545 110/29/090/29/09 110:23:150:23:15 AAMM 246 INDEX Basilone, -

Marine Heavy Helicopter Squadron 362 Marines from Reuniting with Their Families Oct

Hawaii ARINE OLUME UMBER ARINEHOMAS EFFERSON WARD INNING ETRO ORMAT EWSPAPER OVEMBER MVM37, N 42 T J A W M F N N 2, 2007 Training Lion King Sports A-3 B-1 C-1 HMH-362 reunites with families, loved ones Story and Photos by Christine Cabalo Photojournalist A little rain didn’t stop returning Marine Heavy Helicopter Squadron 362 Marines from reuniting with their families Oct. 25 after a seven-month deployment to al Asad, Iraq. Diverted to Hickam Air Force Base in Honolulu, the “Ugly Angels” couldn’t land near Hangar 105 due to wet weather. Buses on standby went to pick up the Marines and return them to Marine Corps Base Hawaii. After a two-hour wait, families and loved ones gathered facing the flight line to welcome home 105 returning Marines. The returning squadron members received an orchid See HMH-362, A-7 Petty Officer 3rd Class Theron J. Gohde, a corpsman with 1st Battalion, 12th Marine Regiment, is greeted by family. The battalion arrived home throughout October, and were welcomed by smiling faces at Hangar 105 here. 1/12 returns from Iraq Story and Photos by Lance Cpl. Regina A. Ruisi Combat Correspondent Marines of 1st Battalion, 12th Marine Regiment returned from an Iraq deployment throughout October, bringing an end to a seven-month tour with Task Force Military Police, 2nd Marine Expeditionary Force (Forward). The deployment marked a special place in the battalion’s history. It was the first time since Desert Storm that the entire battalion deployed to a combat zone at the same time. -

1 THERESA WERNER: the First Mobile Landing Platform Has Been Assigned to Central Command

NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LUNCHEON WITH JONATHAN GREENERT SUBJECT: JONATHAN GREENERT WILL DISCUSS THE STATE OF THE NAVY TODAY AS WELL AS ITS STRATEGY TO AUGMENT NAVAL OPERATIONS IN THE ASIA-PACIFIC. MODERATOR: THERESA WERNER, PRESIDENT, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB LOCATION: NATIONAL PRESS CLUB BALLROOM, WASHINGTON, D.C. TIME: 12:30 P.M. EDT DATE: FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 16, 2012 (C) COPYRIGHT 2008, NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, 529 14TH STREET, WASHINGTON, DC - 20045, USA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. ANY REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION IS EXPRESSLY PROHIBITED. UNAUTHORIZED REPRODUCTION, REDISTRIBUTION OR RETRANSMISSION CONSTITUTES A MISAPPROPRIATION UNDER APPLICABLE UNFAIR COMPETITION LAW, AND THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB RESERVES THE RIGHT TO PURSUE ALL REMEDIES AVAILABLE TO IT IN RESPECT TO SUCH MISAPPROPRIATION. FOR INFORMATION ON BECOMING A MEMBER OF THE NATIONAL PRESS CLUB, PLEASE CALL 202-662-7505. THERESA WERNER: (Sounds gavel.) Good afternoon, and welcome to the National Press Club. My name is Theresa Werner, and I am the 105th president of the National Press Club. We are the world’s leading professional organization for journalists, committed to our profession’s future through our programming and events such as this, while fostering a free press worldwide. For more information about the National Press Club, please visit our website at www.press.org. To donate to programs offered to the public through our National Press Club Journalism Institute, please visit www.press.org/institute. On behalf of our members worldwide, I’d like to welcome our speaker and those of you attending today’s event. Our head table includes guests of our speaker as well as working journalists who are Club members.