Scandinavian Review Nielsen and Sibelius at 150 Autumn—2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Savage and Deformed”: Stigma As Drama in the Tempest Jeffrey R

“Savage and Deformed”: Stigma as Drama in The Tempest Jeffrey R. Wilson The dramatis personae of The Tempest casts Caliban as “asavageand deformed slave.”1 Since the mid-twentieth century, critics have scrutinized Caliban’s status as a “slave,” developing a riveting post-colonial reading of the play, but I want to address the pairing of “savage and deformed.”2 If not Shakespeare’s own mixture of moral and corporeal abominations, “savage and deformed” is the first editorial comment on Caliban, the “and” here Stigmatized as such, Caliban’s body never comes to us .”ס“ working as an uninterpreted. It is always already laden with meaning. But what, if we try to strip away meaning from fact, does Caliban actually look like? The ambiguous and therefore amorphous nature of Caliban’s deformity has been a perennial problem in both dramaturgical and critical studies of The Tempest at least since George Steevens’s edition of the play (1793), acutely since Alden and Virginia Vaughan’s Shakespeare’s Caliban: A Cultural His- tory (1993), and enduringly in recent readings by Paul Franssen, Julia Lup- ton, and Mark Burnett.3 Of all the “deformed” images that actors, artists, and critics have assigned to Caliban, four stand out as the most popular: the devil, the monster, the humanoid, and the racial other. First, thanks to Prospero’s yarn of a “demi-devil” (5.1.272) or a “born devil” (4.1.188) that was “got by the devil himself” (1.2.319), early critics like John Dryden and Joseph War- ton envisioned a demonic Caliban.4 In a second set of images, the reverbera- tions of “monster” in The Tempest have led writers and artists to envision Caliban as one of three prodigies: an earth creature, a fish-like thing, or an animal-headed man. -

Correspondences – Jean Sibelius in a Forest of Image and Myth // Anna-Maria Von Bonsdorff --- FNG Research Issue No

Issue No. 6/20161/2017 CorrespondencesNordic Art History in – the Making: Carl Gustaf JeanEstlander Sibelius and in Tidskrift a Forest för of Bildande Image and Konst Myth och Konstindustri 1875–1876 Anna-Maria von Bonsdorff SusannaPhD, Chief Pettersson Curator, //Finnish PhD, NationalDirector, Gallery,Ateneum Ateneum Art Museum, Art Museum Finnish National Gallery First published in RenjaHanna-Leena Suominen-Kokkonen Paloposki (ed.), (ed.), Sibelius The Challenges and the World of Biographical of Art. Ateneum ResearchPublications in ArtVol. History 70. Helsinki: Today Finnish. Taidehistoriallisia National Gallery tutkimuksia / Ateneum (Studies Art inMuseum, Art History) 2014, 46. Helsinki:81–127. Taidehistorian seura (The Society for Art History in Finland), 64–73, 2013 __________ … “så länge vi på vår sida göra allt hvad i vår magt står – den mår vara hur ringa Thankssom to his helst friends – för in att the skapa arts the ett idea konstorgan, of a young värdigt Jean Sibeliusvårt lands who och was vår the tids composer- fordringar. genius Stockholmof his age developed i December rapidly. 1874. Redaktionen”The figure that. (‘… was as createdlong as wewas do emphatically everything we anguished, can reflective– however and profound. little that On maythe beother – to hand,create pictures an art bodyof Sibelius that is showworth us the a fashionable, claims of our 1 recklesscountries and modern and ofinternational our time. From bohemian, the Editorial whose staff, personality Stockholm, inspired December artists to1874.’) create cartoons and caricatures. Among his many portraitists were the young Akseli Gallen-Kallela1 and the more experienced Albert Edelfelt. They tended to emphasise Sibelius’s high forehead, assertiveThese words hair were and addressedpiercing eyes, to the as readersif calling of attention the first issue to ofhow the this brand charismatic new art journal person created compositionsTidskrift för bildande in his headkonst andoch thenkonstindustri wrote them (Journal down, of Finein their Arts entirety, and Arts andas the Crafts) score. -

PLATTEGROND VAN HET CONCERTGEBOUW Begane Grond 1E

PLATTEGROND VAN HET CONCERTGEBOUW JULI AUGUSTUS Begane grond Entree Café Woensdag 2 augustus 2017 Trap Trap T Grote Zaal 20.00 uur Zuid Würth Philharmoniker Achterzaal Garderobe Dennis Russell Davies, dirigent Voorzaal Podium Robeco Ray Chen, viool Grote Zaal Summer Restaurant Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart 1756-1791 Symfonie nr. 32 in G, KV 318 (1779) Noord Allegro spiritoso Andante Trap Trap Primo tempo Felix Mendelssohn 1809-1847 Vioolconcert in e, op. 64 (1844) Allegro molto appassionato 1e verdieping Andante Pleinfoyer Allegretto non troppo - Allegro molto vivace Museum- SummerNights Live! foyer PAUZE T Trap Trap Antonín Dvořák 1841-1904 Solistenfoyer Negende symfonie in e, op. 95 ‘Uit de Balkon Zuid Nieuwe Wereld’ (1893) Podium Adagio - Allegro molto Frontbalkon Largo Scherzo: Molto vivace Kleine Zaal Grote Zaal Allegro con fuoco Muziek beleven doet u samen. Veel van Podium Balkon Noord onze bezoekers willen optimaal van de muziek genieten door geconcentreerd en in stilte te Dirigenten- luisteren. Wij vragen u daar rekening mee te Trap foyer Trap houden. WWW.ROBECOSUMMERNIGHTS.NL Informatiebeveiliging in de ambulancezorg Toelichting/TOELICHTING/Biografie//Summary//Concerttip BIOGRAFIE SUMMARYjuli-aug 2015 EN VERDER... In januari 1779 keerde Wolfgang Amadeus het nieuwe vioolconcert was onder meer dat De Würth Philharmoniker draagt de naam When Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart worked as Social media Robeco Mozart van zijn reis naar Parijs terug in de solist meteen met de deur in huis komt van zijn initiatiefnemer: de Duitse onderne- the court organist for Count Archbishop Salzburg, waar zijn (ongelukkige) dienstver- vallen, dat de solocadens niet aan het eind mer en mecenas Reinhold Würth. Het gloed- Colloredo in Salzburg, he was expected to Meer Robeco SummerNights online! De Robeco SummerNights komen voort uit band bij prins-aartsbisschop Colloredo werd van het eerste deel zit maar veel eerder, en nieuwe orkest, met het juist gebouwde provide new compositions for the court and Volg Het Concertgebouw op social media en een unieke samenwerking tussen Robeco en voortgezet. -

KONSERTTIELÄMÄ HELSINGISSÄ SOTAVUOSINA 1939–1944 Musiikkielämän Tarjonta, Haasteet Ja Merkitys Poikkeusoloissa

KONSERTTIELÄMÄ HELSINGISSÄ SOTAVUOSINA 1939–1944 Musiikkielämän tarjonta, haasteet ja merkitys poikkeusoloissa Susanna Lehtinen Pro gradu -tutkielma Musiikkitiede Filosofian, historian ja taiteiden tutkimuksen osasto Humanistinen tiedekunta Helsingin yliopisto Lokakuu 2020 Tiedekunta/Osasto – Fakultet/Sektion – Faculty Humanistinen tiedekunta / Filosofian, historian ja taiteiden tutkimuksen osasto Tekijä – Författare – Author Susanna Lehtinen Työn nimi – Arbetets titel – Title Konserttielämä Helsingissä sotavuosina 1939–1944. Musiikkielämän tarjonta, haasteet ja merkitys poikkeusoloissa. Oppiaine – Läroämne – Subject Musiikkitiede Työn laji – Arbetets art – Level Aika – Datum – Month and year Sivumäärä– Sidoantal – Number of pages Pro gradu -tutkielma Lokakuu 2020 117 + Liitteet Tiivistelmä – Referat – Abstract Tässä tutkimuksessa kartoitetaan elävä taidemusiikin konserttitoiminta Helsingissä sotavuosina 1939–1944 eli talvisodan, välirauhan ja jatkosodan ajalta. Tällaista kattavaa musiikkikentän kartoitusta tuolta ajalta ei ole aiemmin tehty. Olennainen tutkimuskysymys on sota-ajan aiheuttamien haasteiden kartoitus. Tutkimalla sotavuosien musiikkielämän ohjelmistopolitiikkaa ja vastaanottoa haetaan vastauksia siihen, miten sota-aika on heijastunut konserteissa ja niiden ohjelmistoissa ja miten merkitykselliseksi yleisö on elävän musiikkielämän kokenut. Tutkimuksen viitekehys on historiallinen. Aineisto on kerätty arkistotutkimuksen menetelmin ja useita eri lähteitä vertailemalla on pyritty mahdollisimman kattavaan kokonaisuuteen. Tutkittava -

DIE LIEBE DER DANAE July 29 – August 7, 2011

DIE LIEBE DER DANAE July 29 – August 7, 2011 the richard b. fisher center for the performing arts at bard college About The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts, an environment for world-class artistic presentation in the Hudson Valley, was designed by Frank Gehry and opened in 2003. Risk-taking performances and provocative programs take place in the 800-seat Sosnoff Theater, a proscenium-arch space; and in the 220-seat Theater Two, which features a flexible seating configuration. The Center is home to Bard College’s Theater and Dance Programs, and host to two annual summer festivals: SummerScape, which offers opera, dance, theater, operetta, film, and cabaret; and the Bard Music Festival, which celebrates its 22nd year in August, with “Sibelius and His World.” The Center bears the name of the late Richard B. Fisher, the former chair of Bard College’s Board of Trustees. This magnificent building is a tribute to his vision and leadership. The outstanding arts events that take place here would not be possible without the contributions made by the Friends of the Fisher Center. We are grateful for their support and welcome all donations. ©2011 Bard College. All rights reserved. Cover Danae and the Shower of Gold (krater detail), ca. 430 bce. Réunion des Musées Nationaux/Art Resource, NY. Inside Back Cover ©Peter Aaron ’68/Esto The Richard B. Fisher Center for the Performing Arts at Bard College Chair Jeanne Donovan Fisher President Leon Botstein Honorary Patron Martti Ahtisaari, Nobel Peace Prize laureate and former president of Finland Die Liebe der Danae (The Love of Danae) Music by Richard Strauss Libretto by Joseph Gregor, after a scenario by Hugo von Hofmannsthal Directed by Kevin Newbury American Symphony Orchestra Conducted by Leon Botstein, Music Director Set Design by Rafael Viñoly and Mimi Lien Choreography by Ken Roht Costume Design by Jessica Jahn Lighting Design by D. -

Sibelius the Tempest: Incidental Music/Finlandia/Karelia Suite - Intermezzo & Alla Marcia/Scenes Historiques/Festivo Mp3, Flac, Wma

Sibelius The Tempest: Incidental Music/Finlandia/Karelia Suite - Intermezzo & Alla Marcia/Scenes Historiques/Festivo mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: The Tempest: Incidental Music/Finlandia/Karelia Suite - Intermezzo & Alla Marcia/Scenes Historiques/Festivo Country: Europe Released: 1990 Style: Romantic MP3 version RAR size: 1802 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1394 mb WMA version RAR size: 1218 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 236 Other Formats: MIDI AIFF DMF RA MP3 DTS MP2 Tracklist Hide Credits The Tempest: Incidental Music Op. 109b & C Orchestra – The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra 1 Caliban's Song 1:21 2 The Oak Tree 2:45 3 Humoresque 1:07 4 Canon 1:32 5 Scene 1:29 6 Berceuse 2:30 7 Chorus Of The Winds 3:24 8 Intermezzo 2:21 9 Dance of the Nymphs 2:11 10 Prospero 1:51 11 Second Song 1:00 12 Miranda 2:23 13 The Naiads 1:11 14 The Tempest 4:06 Festivo, Op. 25, No. 3 (from Scenes Historiques, 1) 15 7:45 Orchestra – The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Scenes Historiques, 2 Engineer – Arthur ClarkOrchestra – The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra 16 The Chase, Op. 66 No. 1 6:34 17 Love Song, Op. 66 No. 2 4:56 18 At The Drawbridge, Op. No. 3 6:48 Karelia Suite Orchestra – BBC Symphony Orchestra 19 Intermezzo, Op. 11 No. 1 3:00 20 Alla Marcia, Op. 11 No. 3 4:32 Finlandia-Symphonic Poem Op. 26 21 Engineer – Arthur Clark*Orchestra – The London 8:54 Philharmonic OrchestraProducer – Walter Legge Credits Composed By – Jean Sibelius Conductor – Sir Thomas Beecham Cover – John Marsh Design Associates Remastered By [Digitally Remastered By] – John Holland Notes Tracks 1-14 - The copyright in these sound recordings is owned by CBS Records Inc, p)1956. -

Osmo Vänskä, Conductor Augustin Hadelich, Violin

Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra 2019-2020 Mellon Grand Classics Season December 6 and 8, 2019 OSMO VÄNSKÄ, CONDUCTOR AUGUSTIN HADELICH, VIOLIN CARL NIELSEN Helios Overture, Opus 17 WOLFGANG AMADEUS Concerto No. 2 in D major for Violin and Orchestra, K. 211 MOZART I. Allegro moderato II. Andante III. Rondeau: Allegro Mr. Hadelich Intermission THOMAS ADÈS Violin Concerto, “Concentric Paths,” Opus 24 I. Rings II. Paths III. Rounds Mr. Hadelich JEAN SIBELIUS Symphony No. 3 in C major, Opus 52 I. Allegro moderato II. Andantino con moto, quasi allegretto III. Moderato — Allegro (ma non tanto) Dec. 6-8, 2019, page 1 PROGRAM NOTES BY DR. RICHARD E. RODDA CARL NIELSEN Helios Overture, Opus 17 (1903) Carl Nielsen was born in Odense, Denmark on June 9, 1865, and died in Copenhagen on October 3, 1931. He composed his Helios Overture in 1903, and it was premiered by the Danish Royal Orchestra conducted by Joan Svendsen on October 8, 1903. These performances mark the Pittsburgh Symphony premiere of the work. The score calls for piccolo, two flutes, two oboes, two clarinets, two bassoons, four horns, three trumpets, three trombones, tuba, timpani and strings. Performance time: approximately 12 minutes. On September 1, 1889, three years after graduating from the Copenhagen Conservatory, Nielsen joined the second violin section of the Royal Chapel Orchestra, a post he held for the next sixteen years while continuing to foster his reputation as a leading figure in Danish music. His reputation as a composer grew with his works of the ensuing decade, most notably the Second Symphony and the opera Saul and David, but he was still financially unable to quit his job with the Chapel Orchestra to devote himself fully to composition. -

Sibelius Society

UNITED KINGDOM SIBELIUS SOCIETY www.sibeliussociety.info NEWSLETTER No. 84 ISSN 1-473-4206 United Kingdom Sibelius Society Newsletter - Issue 84 (January 2019) - CONTENTS - Page 1. Editorial ........................................................................................... 4 2. An Honour for our President by S H P Steadman ..................... 5 3. The Music of What isby Angela Burton ...................................... 7 4. The Seventh Symphonyby Edward Clark ................................... 11 5. Two forthcoming Society concerts by Edward Clark ............... 12 6. Delights and Revelations from Maestro Records by Edward Clark ............................................................................ 13 7. Music You Might Like by Simon Coombs .................................... 20 8. Desert Island Sibelius by Peter Frankland .................................. 25 9. Eugene Ormandy by David Lowe ................................................. 34 10. The Third Symphony and an enduring friendship by Edward Clark ............................................................................. 38 11. Interesting Sibelians on Record by Edward Clark ...................... 42 12. Concert Reviews ............................................................................. 47 13. The Power and the Gloryby Edward Clark ................................ 47 14. A debut Concert by Edward Clark ............................................... 51 15. Music from WW1 by Edward Clark ............................................ 53 16. A -

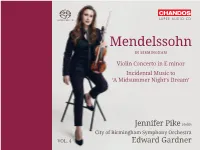

Mendelssohn in BIRMINGHAM

SUPER AUDIO CD Mendelssohn IN BIRMINGHAM Violin Concerto in E minor Incidental Music to ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’ Jennifer Pike violin City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra VOL. 4 Edward Gardner Painting by Thomas Hildebrandt (1804 – 1874) / Stadtgeschichtliches Museum, Leipzig / AKG Images, London Felix Mendelssohn, 1845 Mendelssohn, Felix Felix Mendelssohn (1809 – 1847) Mendelssohn in Birmingham, Volume 4 Concerto, Op. 64* 27:56 in E minor • in e-Moll • en mi mineur for Violin and Orchestra 1 Allegro molto appassionato – Cadenza ad libitum – Tempo I – Più presto – Sempre più presto – Presto – 12:55 2 Andante – Allegretto non troppo – 9:01 3 Allegro molto vivace 6:00 Incidental Music to ‘A Midsummer Night’s Dream’, Op. 61† 39:44 (Ein Sommernachtstraum) by William Shakespeare (1564 – 1616) 4 Overture (Op. 21). Allegro di molto – [ ] – Tempo I – Poco ritenuto 11:25 5 1 Scherzo (After the end of the first act). Allegro vivace 4:30 6 3 Song with Chorus. Allegro ma non troppo 3:57 7 5 Intermezzo (After the end of the second act). Allegro appassionato – Allegro molto comodo 3:21 3 8 7 Notturno (After the end of the third act). Con moto tranquillo 5:34 9 9 Wedding March (After the end of the fourth act). Allegro vivace 4:30 10 11 A Dance of Clowns. Allegro di molto 1:33 11 Finale. Allegro di molto – Un poco ritardando – A tempo I. Allegro molto 4:28 TT 67:57 Rhian Lois soprano I† Keri Fuge soprano II† Jennifer Pike violin* CBSO Youth Chorus† Julian Wilkins chorus master City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra Zoë Beyers leader Edward Gardner 4 Mendelssohn: Violin Concerto in E minor / A Midsummer Night’s Dream Introduction fine violinist himself. -

2005 Summer Bridge

he Sibelius Academy, located in Helsinki, Finland, was founded in T1882. The Academy is named for the internationally renowned and loved Finnish composer Jean Sibelius. As a state music academy, the Sibelius Academy enjoys university status and is an integral part of the system of higher education in Finland. It is the only university of music in Finland, and the largest in Scandinavia. World-class student musicians from the prestigious music academy are invited annually by Finlandia University to present a series of outstanding public performances. This year, three consecutive evening concerts will be presented at the historic Calumet Theatre; an additional festival concert will be presented at the Holy Cross Lutheran Church in Wheaton, IL. summer 2005 This year’s award-winning performers are solo pianist Marko Mustonen, piano-cello duo Anna Kuvaja and Alexander Gebert, and chamber music quartet Soli Amici (Annu Salminen, Performance Dates horn; Paula Kitinoja, oboe; Timo Jäntti, Calumet Theatre Holy Cross Lutheran Church bassoon; and Kaisa Koivula, clarinet; with piano Calumet, MI Wheaton, IL accompanist Jussi Rinta). on August 3 rd, 4 th, and 5 th on August 1st SEVENTH ANNUAL SIBELIUS ACADEMY MUSIC FESTIVAL TICKET ORDER FORM Name: ________________________________________________ CALUMET THEATRE 340 Sixth Stree t • P.O. Box 167 • Calumet, MI 49913 Address: ________________________________________________ Box Office: (906) 337-2610 • Fax: (906) 337-4073 Address: ________________________ Phone: ________________ E-mail: [email protected] http://www.calu mettheatre.com CALUMET THEATRE ONLY Date Artist Tickets Price Qty Best Available Seat On Total Aug. 3, 2005: Soli Amici: chamber music quartet Adult $15 ______ K Main Floor K Balcony $ ______ Jussi Rintä, piano (accompaniment) Student/Senior $10 ______ K Main Floor K Balcony $ ______ Aug. -

Agosto-Setembro

GIANCARLO GUERRERO REGE O CONCERTO PARA PIANO EM LÁ MENOR, DE GRIEG, COM O SOLISTA DMITRY MAYBORODA RECITAIS OSESP: O PIANISTA DMITRY MAYBORODA APRESENTA PEÇAS DE CHOPIN E RACHMANINOV FABIO MARTINO É O SOLISTA NO CONCERTO Nº 5 PARA PIANO, DE VILLA-LOBOS, SOB REGÊNCIA DE EDIÇÃO CELSO ANTUNES Nº 5, 2014 TIMOTHY MCALLISTER INTERPRETA A ESTREIA LATINO-AMERICANA DO CONCERTO PARA SAXOFONE, DE JOHN ADAMS, COENCOMENDA DA OSESP, SOB REGÊNCIA DE MARIN ALSOP OS PIANISTAS BRAD MEHLDAU E KEVIN HAYS APRESENTAM O PROGRAMA ESPECIAL MODERN MUSIC RECITAIS OSESP: JEAN-EFFLAM BAVOUZET, ARTISTA EM RESIDÊNCIA 2014, APRESENTA PEÇAS PARA PIANO DE BEETHOVEN, RAVEL E BARTÓK MÚSICA NA CABEÇA: ENCONTRO COM O COMPOSITOR SERGIO ASSAD O QUARTETO OSESP, COM JEAN-EFFLAM BAVOUZET, APRESENTA A ESTREIA MUNDIAL DE ESTÉTICA DO FRIO III - HOMENAGEM A LEONARD BERNSTEIN, DE CELSO LOUREIRO CHAVES, ENCOMENDA DA OSESP ISABELLE FAUST INTERPRETA O CONCERTO PARA VIOLINO, DE BEETHOVEN, E O CORO DA OSESP APRESENTA TRECHOS DE ÓPERAS DE WAGNER, SOB REGÊNCIA DE FRANK SHIPWAY CLÁUDIO CRUZ REGE A ORQUESTRA DE CÂMARA DA OSESP NA INTERPRETAÇÃO DA ESTREIA MUNDIAL DE SONHOS E MEMÓRIAS, DE SERGIO ASSAD, ENCOMENDA DA OSESP COM SOLOS DE NATAN ALBUQUERQUE JR. A MEZZO SOPRANO CHRISTIANNE STOTIJN INTERPRETA CANÇÕES DE NERUDA, DE PETER LIEBERSON, SOB REGÊNCIA DE LAWRENCE RENES MÚSICA NA CABEÇA: ENCONTRO COM O COMPOSITOR CELSO LOUREIRO CHAVES JUVENTUDE SÔNICa – UM COMPOSITOR EM Desde 2012, a Revista Osesp tem ISSN, BUSCA DE VOZ PRÓPRIA um selo de reconhecimento intelectual JOHN ADAMS 4 e acadêmico. Isso significa que os textos aqui publicados são dignos de referência na área e podem ser indexados nos sistemas nacionais e AGO ago internacionais de pesquisa. -

1 Concert 2 – Nordic Triumph November 16, 2019 Overture To

Concert 2 – Nordic Triumph November 16, 2019 Overture to Maskarade —Carl Nielsen Carl Nielsen is now acknowledged as Denmark’s most distinguished composer, and more than deserving to take his place with Grieg and Sibelius in the pantheon of Scandinavia’s long-revered composers. It was not always so, of course, and it was not until the middle of the twentieth century that his music enjoyed broad admiration, study, and performance. Not that he ever languished in obscurity, for by his forties, he was regarded as Denmark’s leading musician. He grew up in modest circumstances— certainly not a prodigy—studied assiduously, played in several unpretentious ensembles on various instruments, and began composing in small forms. He was intellectually curious, reading and pondering philosophy, history, and literature, and it must be said, was profoundly aided in his overall growth as a composer and in general intellectual sophistication by his long marriage to a remarkable woman. His wife, Anne Marie Brodersen, was a recognized major sculptor, a “strong- willed and modern-minded woman” who was relentless in the pursuit of her own, very successful career as an artist. Her independence—and penchant for frequently leaving the family to pursue her own career—impacted the tranquility of the marriage, without doubt. But, she was a stimulating, strong partner that unquestionably aided in his development into an artist of spiritual depth and sophistication. Nielsen’s reputation outside of Denmark is largely sustained by his six symphonies—Leonard Bernstein was an influential international champion of them—but he composed actively in almost all major genres.