Valse Triste, Op. 44, No. 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Savage and Deformed”: Stigma As Drama in the Tempest Jeffrey R

“Savage and Deformed”: Stigma as Drama in The Tempest Jeffrey R. Wilson The dramatis personae of The Tempest casts Caliban as “asavageand deformed slave.”1 Since the mid-twentieth century, critics have scrutinized Caliban’s status as a “slave,” developing a riveting post-colonial reading of the play, but I want to address the pairing of “savage and deformed.”2 If not Shakespeare’s own mixture of moral and corporeal abominations, “savage and deformed” is the first editorial comment on Caliban, the “and” here Stigmatized as such, Caliban’s body never comes to us .”ס“ working as an uninterpreted. It is always already laden with meaning. But what, if we try to strip away meaning from fact, does Caliban actually look like? The ambiguous and therefore amorphous nature of Caliban’s deformity has been a perennial problem in both dramaturgical and critical studies of The Tempest at least since George Steevens’s edition of the play (1793), acutely since Alden and Virginia Vaughan’s Shakespeare’s Caliban: A Cultural His- tory (1993), and enduringly in recent readings by Paul Franssen, Julia Lup- ton, and Mark Burnett.3 Of all the “deformed” images that actors, artists, and critics have assigned to Caliban, four stand out as the most popular: the devil, the monster, the humanoid, and the racial other. First, thanks to Prospero’s yarn of a “demi-devil” (5.1.272) or a “born devil” (4.1.188) that was “got by the devil himself” (1.2.319), early critics like John Dryden and Joseph War- ton envisioned a demonic Caliban.4 In a second set of images, the reverbera- tions of “monster” in The Tempest have led writers and artists to envision Caliban as one of three prodigies: an earth creature, a fish-like thing, or an animal-headed man. -

Correspondences – Jean Sibelius in a Forest of Image and Myth // Anna-Maria Von Bonsdorff --- FNG Research Issue No

Issue No. 6/20161/2017 CorrespondencesNordic Art History in – the Making: Carl Gustaf JeanEstlander Sibelius and in Tidskrift a Forest för of Bildande Image and Konst Myth och Konstindustri 1875–1876 Anna-Maria von Bonsdorff SusannaPhD, Chief Pettersson Curator, //Finnish PhD, NationalDirector, Gallery,Ateneum Ateneum Art Museum, Art Museum Finnish National Gallery First published in RenjaHanna-Leena Suominen-Kokkonen Paloposki (ed.), (ed.), Sibelius The Challenges and the World of Biographical of Art. Ateneum ResearchPublications in ArtVol. History 70. Helsinki: Today Finnish. Taidehistoriallisia National Gallery tutkimuksia / Ateneum (Studies Art inMuseum, Art History) 2014, 46. Helsinki:81–127. Taidehistorian seura (The Society for Art History in Finland), 64–73, 2013 __________ … “så länge vi på vår sida göra allt hvad i vår magt står – den mår vara hur ringa Thankssom to his helst friends – för in att the skapa arts the ett idea konstorgan, of a young värdigt Jean Sibeliusvårt lands who och was vår the tids composer- fordringar. genius Stockholmof his age developed i December rapidly. 1874. Redaktionen”The figure that. (‘… was as createdlong as wewas do emphatically everything we anguished, can reflective– however and profound. little that On maythe beother – to hand,create pictures an art bodyof Sibelius that is showworth us the a fashionable, claims of our 1 recklesscountries and modern and ofinternational our time. From bohemian, the Editorial whose staff, personality Stockholm, inspired December artists to1874.’) create cartoons and caricatures. Among his many portraitists were the young Akseli Gallen-Kallela1 and the more experienced Albert Edelfelt. They tended to emphasise Sibelius’s high forehead, assertiveThese words hair were and addressedpiercing eyes, to the as readersif calling of attention the first issue to ofhow the this brand charismatic new art journal person created compositionsTidskrift för bildande in his headkonst andoch thenkonstindustri wrote them (Journal down, of Finein their Arts entirety, and Arts andas the Crafts) score. -

Sibelius the Tempest: Incidental Music/Finlandia/Karelia Suite - Intermezzo & Alla Marcia/Scenes Historiques/Festivo Mp3, Flac, Wma

Sibelius The Tempest: Incidental Music/Finlandia/Karelia Suite - Intermezzo & Alla Marcia/Scenes Historiques/Festivo mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Classical Album: The Tempest: Incidental Music/Finlandia/Karelia Suite - Intermezzo & Alla Marcia/Scenes Historiques/Festivo Country: Europe Released: 1990 Style: Romantic MP3 version RAR size: 1802 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1394 mb WMA version RAR size: 1218 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 236 Other Formats: MIDI AIFF DMF RA MP3 DTS MP2 Tracklist Hide Credits The Tempest: Incidental Music Op. 109b & C Orchestra – The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra 1 Caliban's Song 1:21 2 The Oak Tree 2:45 3 Humoresque 1:07 4 Canon 1:32 5 Scene 1:29 6 Berceuse 2:30 7 Chorus Of The Winds 3:24 8 Intermezzo 2:21 9 Dance of the Nymphs 2:11 10 Prospero 1:51 11 Second Song 1:00 12 Miranda 2:23 13 The Naiads 1:11 14 The Tempest 4:06 Festivo, Op. 25, No. 3 (from Scenes Historiques, 1) 15 7:45 Orchestra – The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra Scenes Historiques, 2 Engineer – Arthur ClarkOrchestra – The Royal Philharmonic Orchestra 16 The Chase, Op. 66 No. 1 6:34 17 Love Song, Op. 66 No. 2 4:56 18 At The Drawbridge, Op. No. 3 6:48 Karelia Suite Orchestra – BBC Symphony Orchestra 19 Intermezzo, Op. 11 No. 1 3:00 20 Alla Marcia, Op. 11 No. 3 4:32 Finlandia-Symphonic Poem Op. 26 21 Engineer – Arthur Clark*Orchestra – The London 8:54 Philharmonic OrchestraProducer – Walter Legge Credits Composed By – Jean Sibelius Conductor – Sir Thomas Beecham Cover – John Marsh Design Associates Remastered By [Digitally Remastered By] – John Holland Notes Tracks 1-14 - The copyright in these sound recordings is owned by CBS Records Inc, p)1956. -

Sibelius Society

UNITED KINGDOM SIBELIUS SOCIETY www.sibeliussociety.info NEWSLETTER No. 84 ISSN 1-473-4206 United Kingdom Sibelius Society Newsletter - Issue 84 (January 2019) - CONTENTS - Page 1. Editorial ........................................................................................... 4 2. An Honour for our President by S H P Steadman ..................... 5 3. The Music of What isby Angela Burton ...................................... 7 4. The Seventh Symphonyby Edward Clark ................................... 11 5. Two forthcoming Society concerts by Edward Clark ............... 12 6. Delights and Revelations from Maestro Records by Edward Clark ............................................................................ 13 7. Music You Might Like by Simon Coombs .................................... 20 8. Desert Island Sibelius by Peter Frankland .................................. 25 9. Eugene Ormandy by David Lowe ................................................. 34 10. The Third Symphony and an enduring friendship by Edward Clark ............................................................................. 38 11. Interesting Sibelians on Record by Edward Clark ...................... 42 12. Concert Reviews ............................................................................. 47 13. The Power and the Gloryby Edward Clark ................................ 47 14. A debut Concert by Edward Clark ............................................... 51 15. Music from WW1 by Edward Clark ............................................ 53 16. A -

Unc Symphony Orchestra Library

UNC ORCHESTRA LIBRARY HOLDINGS Anderson Fiddle-Faddle Anderson The Penny-Whistle Song Anderson Plink, Plank, Plunk! Anderson A Trumpeter’s Lullaby Arensky Silhouettes, Op. 23 Arensky Variations on a Theme by Tchaikovsky, Op. 35a Bach, J.C. Domine ad adjuvandum Bach, J.C. Laudate pueri Bach Cantata No. 106, “Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit” Bach Cantata No. 140, “Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme” Bach Cantata No. 209, “Non sa che sia dolore” Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 1 in F major, BWV 1046 Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 2 in F major, BWV 1047 Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 3 in G major, BWV 1048 Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 4 in G major, BWV 1049 Bach Brandenburg Concerto No. 5 in D major, BWV 1050 Bach Clavier Concerto No. 4 in A major, BWV 1055 Bach Clavier Concerto No. 7 in G minor, BWV 1058 Bach Concerto No. 1 in C minor for Two Claviers, BWV 1060 Bach Concerto No. 2 in C major for Three Claviers, BWV 1064 Bach Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, BWV 1041 Bach Concerto in D minor for Two Violins, BWV 1043 Bach Komm, süsser Tod Bach Magnificat in D major, BWV 243 Bach A Mighty Fortress Is Our God Bach O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde gross, BWV 622 Bach Prelude, Choral and Fugue Bach Suite No. 3 in D major, BWV 1068 Bach Suite in B minor Bach Adagio from Toccata, Adagio and Fugue in C major, BWV 564 Bach Toccata and Fugue in D minor, BWV 565 Barber Adagio for Strings, Op. -

A Christian Physicist Examines Noah's Flood and Plate Tectonics

A Christian Physicist Examines Noah’s Flood and Plate Tectonics by Steven Ball, Ph.D. September 2003 Dedication I dedicate this work to my friend and colleague Rodric White-Stevens, who delighted in discussing with me the geologic wonders of the Earth and their relevance to Biblical faith. Cover picture courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey, copyright free 1 Introduction It seems that no subject stirs the passions of those intending to defend biblical truth more than Noah’s Flood. It is perhaps the one biblical account that appears to conflict with modern science more than any other. Many aspiring Christian apologists have chosen to use this account as a litmus test of whether one accepts the Bible or modern science as true. Before we examine this together, let me clarify that I accept the account of Noah’s Flood as completely true, just as I do the entirety of the Bible. The Bible demonstrates itself to be reliable and remarkably consistent, having numerous interesting participants in various stories through which is interwoven a continuous theme of God’s plan for man’s redemption. Noah’s Flood is one of those stories, revealing to us both God’s judgment of sin and God’s over-riding grace and mercy. It remains a timeless account, for it has much to teach us about a God who never changes. It is one of the most popular Bible stories for children, and the truth be known, for us adults as well. It is rather unfortunate that many dismiss the account as mythical, simply because it seems to be at odds with a scientific view of the earth. -

Virtual Edition in Honor of the 74Th Festival

ARA GUZELIMIAN artistic director 0611-142020* Save-the-Dates 75th Festival June 10-13, 2021 JOHN ADAMS music director “Ojai, 76th Festival June 9-12, 2022 a Musical AMOC music director Virtual Edition th Utopia. – New York Times *in honor of the 74 Festival OjaiFestival.org 805 646 2053 @ojaifestivals Welcome to the To mark the 74th Festival and honor its spirit, we bring to you this keepsake program book as our thanks for your steadfast support, a gift from the Ojai Music Festival Board of Directors. Contents Thursday, June 11 PAGE PAGE 2 Message from the Chairman 8 Concert 4 Virtual Festival Schedule 5 Matthias Pintscher, Music Director Bio Friday, June 12 Music Director Roster PAGE 12 Ojai Dawns 6 The Art of Transitions by Thomas May 16 Concert 47 Festival: Future Forward by Ara Guzelimian 20 Concert 48 2019-20 Annual Giving Contributors 51 BRAVO Education & Community Programs Saturday, June 13 52 Staff & Production PAGE 24 Ojai Dawns 28 Concert 32 Concert Sunday, June 14 PAGE 36 Concert 40 Concert 44 Concert for Ojai Cover art: Mimi Archie 74 TH OJAI MUSIC FESTIVAL | VIRTUAL EDITION PROGRAM 2020 | 1 A Message from the Chairman of the Board VISION STATEMENT Transcendent and immersive musical experiences that spark joy, challenge the mind, and ignite the spirit. Welcome to the 74th Ojai Music Festival, virtual edition. Never could we daily playlists that highlight the 2020 repertoire. Our hope is, in this very modest way, to honor the spirit of the 74th have predicted how altered this moment would be for each and every MISSION STATEMENT Ojai Music Festival, to pay tribute to those who imagined what might have been, and to thank you for being unwavering one of us. -

Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto

Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto Friday, January 12, 2018 at 11 am Jayce Ogren, Guest conductor Sibelius Symphony No. 7 in C Major Tchaikovsky Concerto for Violin and Orchestra Gabriel Lefkowitz, violin Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto For Tchaikovsky and The Composers Sibelius, these works were departures from their previ- ous compositions. Both Jean Sibelius were composed in later pe- (1865—1957) riods in these composers’ lives and both were pushing Johan Christian Julius (Jean) Sibelius their comfort levels. was born on December 8, 1865 in Hämeenlinna, Finland. His father (a doctor) died when Jean For Tchaikovsky, the was three. After his father’s death, the family Violin Concerto came on had to live with a variety of relatives and it was Jean’s aunt who taught him to read music and the heels of his “year of play the piano. In his teen years, Jean learned the hell” that included his disas- violin and was a quick study. He formed a trio trous marriage. It was also with his sister older Linda (piano) and his younger brother Christian (cello) and also start- the only concerto he would ed composing, primarily for family. When Jean write for the violin. was ready to attend university, most of his fami- Jean Sibelius ly (Christian stayed behind) moved to Helsinki For Sibelius, his final where Jean enrolled in law symphony became a chal- school but also took classes at the Helsinksi Music In- stitute. Sibelius quickly became known as a skilled vio- lenge to synthesize the tra- linist as well as composer. He then spent the next few ditional symphonic form years in Berlin and Vienna gaining more experience as a composer and upon his return to Helsinki in 1892, he with a tone poem. -

Download Program Notes

Symphony No. 2 in D major, Op. 43 Jean Sibelius hanks to benefactions arranged by Axel four tone poems based on characters from TCarpelan, a Finnish man-about-the-arts Dante’s Divine Comedy . But once Sibelius re - and the eventual dedicatee of this work, Jean turned to Finland that June, he began to rec - Sibelius and his family were able to undertake ognize that what was forming out of his a trip to Italy from February to April 1901. So sketches was instead a full-fledged sym - it was that much of the Second Symphony phony — one that would end up exhibiting was sketched in the Italian cities of Florence an extraordinary degree of unity among its and, especially, Rapallo, where Sibelius sections. With his goal now clarified, Sibelius rented a composing studio apart from the worked assiduously through the summer and home in which his family was lodging. fall and reached a provisional completion of Aspects of the piece had already begun to his symphony in November 1901. Then he form in his mind almost two years earlier, al - had second thoughts, revised the piece pro - though at that point Sibelius seems to have foundly, and definitively concluded the Sec - assumed that his sketches would end up in ond Symphony in January 1902. various separate compositions rather than in The work’s premiere, two months later, a single unified symphony. Even in Rapallo marked a signal success, as did three sold-out he was focused on writing a tone poem. He performances during the ensuing week. The reported that on February 11, 1901, he enter - conductor Robert Kajanus, who would be - tained a fantasy that the villa in which his come a distinguished interpreter of Sibelius’s studio was located was the fanciful palace of works, was in attendance, and he insisted Don Juan and that he himself was the that the Helsinki audiences had understood amorous, amoral protagonist of that legend. -

5 Noah and the Flood

5 Noah and the Flood Read Genesis 6–9 Go into the ark, you and all your household, for I have seen that you alone are righteous. Genesis 7:ı he story of Noah is told to illustrate how deeply the human Tfamily has fallen into sinfulness. Sin is now so universal that a troubled God decides to complete the work of destruction that the human family has begun (Genesis 6:13). However, God sees that Noah is a good man and decides that humanity will survive through Noah’s family. God tells Noah to build an ark, which God will use to save Noah’s family and members of the animal kingdom. God is pained by and disappointed in humankind, but in his mercy he will save the human family through Noah. Noah builds the ark and, following God’s instructions, loads himself, his family, and the animals into it. God closes the door of the ark, showing his care for all inside and for the future human family. The flood comes, joining the waters of the sky with the waters on the earth. As the ark floats higher, everything beneath 11 12 • Noah and the Flood it drowns. For forty days and nights it rains. It is another 150 days before the water recedes. Then God remembers Noah. In his remembering, God begins the process of re-creation: “And God made a wind blow over the earth, and the waters subsided” (Genesis 8:1). Noah sends out birds to see if it is safe to disembark. He first sends a raven, then a dove. -

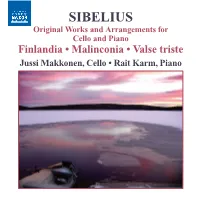

Sibelius:570034Bk Hasse 15/1/08 9:17 PM Page 4

570797bk Sibelius:570034bk Hasse 15/1/08 9:17 PM Page 4 competitions for young pianists in Czechoslovakia and Estonia. Karm has performed widely as a soloist, chamber musician, entertainment and Lied pianist in Finland, Estonia, Germany, Switzerland, Austria, Italy, Hungary Czech Republic and the USA. He has worked with a number of artists including Johanna Rusanen, Helena Juntunen, Pille SIBELIUS Lill, Marion Melnik, Angelika Klas, Heli Veskus, Petteri Iivonen, Jussi Makkonen, and Sami Junnonen. Sponsors in recent years include The Foundation for Finnish Art Music, the Estonia Foundation, the Paulo Foundation and the Wihuri Foundation. Karm is a founding partner of the music agency Music Nova (www.musicnova.fi) and is currently Original Works and Arrangements for its Artistic Director. For information on concerts and other news, please visit the artist’s homepage www.raitkarm.com Cello and Piano Finlandia • Malinconia • Valse triste Jussi Makkonen, Cello • Rait Karm, Piano C M Jussi Makkonen and Rait Karm at Sibelius’ home, Y Ainola, Finland Photo by Lido Salonen K 8.570797 4 570797bk Sibelius:570034bk Hasse 15/1/08 9:17 PM Page 2 Jean Sibelius (1865–1957) optional alternative to the violin. Malinconia (Melancholy), by Josef Julius Wecksell, and Den första kyssen (The First Original Works and Arrangements for Cello and Piano an original work for cello and piano, was written in 1900, Kiss), written in 1900, of words by Runeberg. perhaps reflecting the composer’s feelings after the death of Valse triste has long been isolated from its context. The The Finnish composer Jean Sibelius was born in 1865, the high, although there were inevitable reactions to the his infant daughter Kirsti, or perhaps, it has been suggested, piece was dramatic in origin, written as part of the incidental son of a doctor, in a small town in the south of Finland, the excessive enthusiasm of his supporters. -

THOMAS SØNDERGÅRD BBC National Orchestra of Wales Sibelius Menu

THOMAS SØNDERGÅRD BBC National Orchestra of Wales Sibelius Menu Tracklist Credits Programme Note Biographies THOMAS SØNDERGÅRD BBC National Orchestra of Wales Jean Sibelius (1865 –1957) Symphony No. 1 in E minor, Op. 39 1. Andante, ma non troppo – Allegro energico ................................... 11:2 0 2. Andante ............................................................................................. 9:29 3. Scherzo: Allegro .................................................................................. 5:15 4. Finale (Quasi una fantasia): Andante – Allegro molto ..................... 12:06 Symphony No. 6, Op. 104 5. Allegro molto moderato .................................................................... 8:05 6. Allegretto moderato .......................................................................... 6:10 7. Poco vivace ....................................................................................... 4:04 8. Allegro molto .................................................................................... 10:11 Total Running Time: 66 minutes RECORDED AT POST-PRODUCTION BY BBC Hoddinott Hall, Cardiff, UK Julia Thomas 3–5 December 2014 COVER IMAGE BY PRODUCED BY Euan Robertson Philip Hobbs and Tim Thorne DESIGN BY RECORDED BY toucari.live Philip Hobbs and Robert Cammidge Produced in association with The BBC Radio 3 and BBC National Orchestra of Wales word marks and logos are trade marks of the British Broadcasting Corporation and used under licence. BBC logo © BBC 2017. ‘ like this type of Nordic Italianate