Criminal Detention in the EU – Conditions and Monitoring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

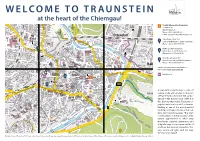

Welcome to Traunstein

r. S t tr c S rs traße h f- ue e s u rf a ß ß O n e a ol l l- K e r F L s ar hS ß t h r S u t r c c C e s a c d r a h w a i E i r Z S u l s t i ß le a s r s g e e ep . t r e c - Ka tr s l s h T n ns ra . il . lle n - Sc h b h hl e ß c S o ß ßs o e Z t a S n t ra r s A B ße r C r D E F G H I J K m e e t a u t t r . e m . s c a n aß e h tr e d - n s i ß S eder Su .- s i E t Fl R S S r t i o . r fs c l o r h a o t h d r e s g K s a Hurt n c e e w ß w r ß S K n n r e e e e me e h B ir s lu i c g c P t B s a a h fa r s Z c b r . t h e r r m e rg h a a ß o i a Zweckham str. R ß e tr Partenhausen f e a rs s s a bu t g t if ß m r. -

Demographisches Profil Für Den Landkreis Ostallgäu

Beiträge zur Statistik Bayerns, Heft 553 Regionalisierte Bevölkerungsvorausberechnung für Bayern bis 2039 x Demographisches Profil für den xLandkreis Ostallgäu Hrsg. im Dezember 2020 Bestellnr. A182AB 202000 www.statistik.bayern.de/demographie Zeichenerklärung Auf- und Abrunden 0 mehr als nichts, aber weniger als die Hälfte der kleins- Im Allgemeinen ist ohne Rücksicht auf die Endsummen ten in der Tabelle nachgewiesenen Einheit auf- bzw. abgerundet worden. Deshalb können sich bei der Sum mierung von Einzelangaben geringfügige Ab- – nichts vorhanden oder keine Veränderung weichun gen zu den ausgewiesenen Endsummen ergeben. / keine Angaben, da Zahlen nicht sicher genug Bei der Aufglie derung der Gesamtheit in Prozent kann die Summe der Einzel werte wegen Rundens vom Wert 100 % · Zahlenwert unbekannt, geheimzuhalten oder nicht abweichen. Eine Abstimmung auf 100 % erfolgt im Allge- rechenbar meinen nicht. ... Angabe fällt später an X Tabellenfach gesperrt, da Aussage nicht sinnvoll ( ) Nachweis unter dem Vorbehalt, dass der Zahlenwert erhebliche Fehler aufweisen kann p vorläufiges Ergebnis r berichtigtes Ergebnis s geschätztes Ergebnis D Durchschnitt ‡ entspricht Publikationsservice Das Bayerische Landesamt für Statistik veröffentlicht jährlich über 400 Publikationen. Das aktuelle Veröffentlichungsverzeich- nis ist im Internet als Datei verfügbar, kann aber auch als Druckversion kostenlos zugesandt werden. Kostenlos Publikationsservice ist der Download der meisten Veröffentlichungen, z.B. von Alle Veröffentlichungen sind im Internet Statistischen -

Collective Marketing of the Murnau Werdenfelser Cattle

WP 2 – Identification of Best Practices in the Collective Commercial Valorisation of Alpine Food ICH WP leader: Kedge Business School Activity A.T2.2 Field Study of Relevant Cases of Success: Collective Marketing of the Murnau Werdenfelser Cattle Involved partners: Florian Ortanderl Munich University of Applied Sciences This project is co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund through the Interreg Alpine Space programme. Abstract In Upper Bavaria, a network of farmers, butchers, restaurants, NGOs and a specially developed trade company cooperate in the safeguarding and valorisation of the endangered cattle breed Murnau Werdenfelser. The company MuWe Fleischhandels GmbH manages large parts of the value creation chain, from the butchering and packaging, to the distribution and marketing activities for the beef products. It pays the farmers a price premium and manages to achieve higher prices for both beef products and beef dishes in restaurants. The activities of the network significantly contributed to the safeguarding and livestock recovery of the endangered cattle breed. Kurzfassung In Oberbayern arbeitet ein Netzwerk aus Landwirten, Metzgern, Restaurants, NGOs und einem speziell dafür entwickelten Unternehmen an der Erhaltung und In-Wert-Setzung der bedrohten Rinderrasse Murnau-Werdenfelser. Das Unternehmen MuWe Fleischhandels GmbH organisiert große Teile der Wertschöpfungskette, von der Metzgerei und der Verpackung, bis zur Distribution und allen Marketing Aktivitäten für die Rindfleischprodukte. Es zahlt den Landwirten einen Preiszuschlag und erzielt Premiumpreise für die Rindfleischprodukte, als auch für Rindfleischgerichte in Restaurants. Die Aktivitäten des Netzwerks haben entscheidend zur Erhaltung und Erholung der Bestände der bedrohten Rinderrasse beigetragen. 1.1 Case typology and historical background This case report analyses a network-based marketing approach for beef products and dishes of the endangered Bavarian cattle breed Murnau Werdenfelser. -

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 As of December, 2009 Club Fam

Summary of Family Membership and Gender by Club MBR0018 as of December, 2009 Club Fam. Unit Fam. Unit Club Ttl. Club Ttl. District Number Club Name HH's 1/2 Dues Females Male TOTAL District 111BS 21847 AUGSBURG 0 0 0 35 35 District 111BS 21848 AUGSBURG RAETIA 0 0 1 49 50 District 111BS 21849 BAD REICHENHALL 0 0 2 25 27 District 111BS 21850 BAD TOELZ 0 0 0 36 36 District 111BS 21851 BAD WORISHOFEN MINDELHEIM 0 0 0 43 43 District 111BS 21852 PRIEN AM CHIEMSEE 0 0 0 36 36 District 111BS 21853 FREISING 0 0 0 48 48 District 111BS 21854 FRIEDRICHSHAFEN 0 0 0 43 43 District 111BS 21855 FUESSEN ALLGAEU 0 0 1 33 34 District 111BS 21856 GARMISCH PARTENKIRCHEN 0 0 0 45 45 District 111BS 21857 MUENCHEN GRUENWALD 0 0 1 43 44 District 111BS 21858 INGOLSTADT 0 0 0 62 62 District 111BS 21859 MUENCHEN ISARTAL 0 0 1 27 28 District 111BS 21860 KAUFBEUREN 0 0 0 33 33 District 111BS 21861 KEMPTEN ALLGAEU 0 0 0 45 45 District 111BS 21862 LANDSBERG AM LECH 0 0 1 36 37 District 111BS 21863 LINDAU 0 0 2 33 35 District 111BS 21864 MEMMINGEN 0 0 0 57 57 District 111BS 21865 MITTELSCHWABEN 0 0 0 42 42 District 111BS 21866 MITTENWALD 0 0 0 31 31 District 111BS 21867 MUENCHEN 0 0 0 35 35 District 111BS 21868 MUENCHEN ARABELLAPARK 0 0 0 32 32 District 111BS 21869 MUENCHEN-ALT-SCHWABING 0 0 0 34 34 District 111BS 21870 MUENCHEN BAVARIA 0 0 0 31 31 District 111BS 21871 MUENCHEN SOLLN 0 0 0 29 29 District 111BS 21872 MUENCHEN NYMPHENBURG 0 0 0 32 32 District 111BS 21873 MUENCHEN RESIDENZ 0 0 0 22 22 District 111BS 21874 MUENCHEN WUERMTAL 0 0 0 31 31 District 111BS 21875 -

Allgemeinverfügung Des Landratsamtes Garmisch-Partenkirchen Vom 16.06.2006 – Abt

A M T S B L A T T FÜR DEN LANDKREIS TRAUNSTEIN Herausgegeben vom Landratsamt Traunstein Erscheint i. d. Regel wöchentlich Bezugspreis vierteljährlich 0,60 € zzgl. Porto Einzelpreis 0,05 € Zu beziehen unmittelbar beim Landratsamt Traunstein oder über die Gemeindeverwaltungen Nr. 25 83278 Traunstein, den 23. Juni 2006 Seite 123 Inhaltsverzeichnis: Sitzung des Jugendhilfeausschusses 66/25 Allgemeinverfügung des Landratsamtes Garmisch-Partenkirchen vom 16.06.2006 – Abt. 5 – im Fall des Braunbären „JJ1“; 67/25 Allgemeinverfügung des Landratsamtes Garmisch-Partenkirchen vom 16.06.2006 – Abt. 5 – im Fall des Braunbären „JJ1“; 68/25 Seite 124 Amtsblatt für den Landkreis Traunstein Nr. 25 ............................................................................................................................................................................................................ 66/06 23-421/111 Sitzung des Jugendhilfeausschusses gemäß §§ 70 Abs. 1 und 71 Abs. 2 SGB VIII sowie § 6 Abs. 7 der Satzung für das Amt für Kinder, Jugend und Familie des Landkreises Traunstein habe ich den Jugendhilfeausschuss für Dienstag, den 27.06.2006, 9.00 Uhr zu einer ordentlichen Sitzung eingeladen. Tagesordnung: TOP 1 Kreisjugendring Traunstein – Grundlagenvertrag – TOP 2 Raumvorgaben für Kindertageseinrichtungen TOP 3 Richtlinien für Vollzeit- und Tagespflege TOP 4 Kooperation zwischen Jugendhilfe und Suchthilfe TOP 5 Jugendsozialarbeit an Schulen TOP 6 Bericht über das Mütterzentrum Traunstein TOP 7 Verschiedenes/Wünsche/Anträge Georg Klausner Stellvertreter des Landrats --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- 67/06 SG 35-B 131/1-1 Allgemeinverfügung des Landratsamtes Garmisch-Partenkirchen vom 13.06.2006 – Abt. 5 - bezüglich des Suchens, des Stellens, des Fangens und des Tötens des Braunbären „JJ1“; Das Landratsamt Garmisch-Partenkirchen hat am 13.06.2006 – Az.: Abt. 5 - u. a. auch für den Bereich des Landkreises Traunstein folgende Allgemeinverfügung erlassen: Allgemeinverfügung: 1. -

Steiner, Klaus, CSU

Steiner, Klaus, CSU Judicial officer, senior civil servant (retired) Personal details Born 07 October 1953 in Übersee Personal status married, 3 children Religion Roman Catholic Parliamentary duties and other posts • Member of the Committee on Food, Agriculture and Forestry • Member of the Committee for the Environment and Consumer Protection • Chairman of the advisory board of JVA Bernau prison • Member of the advisory board of Bayerische Staatsforsten [Bavarian State Forestry Commission] Member of the Bavarian State Parliament: since 20 October 2008 Profile 1975-1978: Studied at the Beamtenfachhochschule [school of public administration] 1978-1989: Judicial officer at Traunstein Local Court and the Munich public prosecution service 1989-2003: CSU parliamentary group advisor 2003-2008: Personal aide to the President of the State Parliament Since 20 October 2008: Member of the Bavarian State Parliament 1970: Joined the Katholische Landjugend Catholic rural youth organisation and active in youth work 1972: Joined the CSU 1973-1980: JU [Young Conservatives] local chairman 1980-1986 JU county vice chairman 1984-2004: CSU local chairman in Übersee 1990 to 2003: Local councillor and group spokesman 1998 to 2008: Member of Upper Bavaria district council Since 2003: County councillor 2003-2017: CSU county chairman for the Traunstein county. District vice chairman of the CSU regional working group on policing; Member of the advisory board of Freundeskreis Frauenchiemsee friends' association; Member of the Netzwerk Hospiz hospice network in the county of Traunstein; Member of the Bayernbund heritage society; Member of Europa-Union; CSU Page 2 Bavarian State Parliament group spokesman on development policy. Other roles in the CSU group: Working group on education and church affairs; Working group on food, agriculture and forestry; Working group on debureaucratisation and decentralisation; Working group on special schools and inclusion; Working group on tourism. -

Germany (Territory Under Allied Occupation, 1945-1955 : U.S

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt0b69r4qg No online items An Inventory of the Germany (Territory under Allied occupation, 1945-1955 : U.S. Zone) Office of Military Government for Bavaria. Kreis Traunstein records Processed by Lyalya Kharitonova. Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California 94305-6010 Phone: (650) 723-3563 Fax: (650) 725-3445 Email: [email protected] © 2010 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. XX416 1 An Inventory of the Germany (Territory under Allied occupation, 1945-1955 : U.S. Zone) Office of Military Government for Bavaria. Kreis Traunstein records Hoover Institution Archives Stanford University Stanford, California Processed by: Lyalya Kharitonova Date Completed: 2010 Encoded by: Machine-readable finding aid derived from MARC record by David Sun and Supriya Wronkiewicz. © 2010 Hoover Institution Archives. All rights reserved. Collection Summary Title: Germany (Territory under Allied occupation, 1945-1955 : U.S. Zone) Office of Military Government for Bavaria. Kreis Traunstein records Dates: 1945-1948 Collection Number: XX416 Creator: Germany (Territory under Allied occupation, 1945-1955 : U.S. Zone) Office of Military Government for Bavaria. Kreis Traunstein. Collection Size: 13 manuscript boxes (5.2 linear feet) Repository: Hoover Institution Archives Stanford, California 94305-6010 Abstract: The records of American administration of occupied Germany (U.S. Zone), Kreis Traunstein relating to civil administration, including problems of public health and safety, administration of justice, allocation of economic recourses, organization of labor, denazification, and disposition of displaced persons contain memoranda, reports, correspondence, and office files. The collection also presents annual administrative reports on civilian relief efforts for other districts in Bavaria. Physical Location: Hoover Institution Archives Languages: English German Access Collection is open for research. -

Oberbayern Strukturdaten IHK München

Strukturdaten IHK München Oberbayern IHK-Unternehmensstatistik IHK-Unternehmen 2019 nach Wirtschaftsabschnitten* Land- und Forstwirtschaft Produzierendes Gewerbe Großhandel HR** KGT*** Gesamt HR** KGT*** Gesamt HR** KGT*** Gesamt Stadt Ingolstadt 3 11 14 338 903 1.241 189 118 307 Stadt München 36 69 105 4.050 8.286 12.336 3.629 2.200 5.829 Stadt Rosenheim 3 10 13 195 426 621 143 91 234 Lkr. Altötting 12 76 88 279 1.545 1.824 116 130 246 Lkr. Bad Tölz-Wolfratshausen 5 172 177 468 1.271 1.739 206 180 386 Lkr. Berchtesgadener Land 6 87 93 311 964 1.275 233 132 365 Lkr. Dachau 14 74 88 477 1.970 2.447 279 201 480 Lkr. Ebersberg 10 119 129 407 1.556 1.963 275 151 426 Lkr. Eichstätt 7 70 77 349 1.932 2.281 127 140 267 Lkr. Erding 15 135 150 354 1.601 1.955 194 194 388 Lkr. Freising 12 73 85 520 2.350 2.870 340 194 534 Lkr. Fürstenfeldbruck 4 65 69 524 2.012 2.536 403 206 609 Lkr. Garmisch-Partenkirchen 5 71 76 204 790 994 130 109 239 Lkr. Landsberg am Lech 7 95 102 382 1.990 2.372 201 214 415 Lkr. Miesbach 13 113 126 368 1.118 1.486 184 152 336 Lkr. Mühldorf am Inn 14 130 144 387 1.654 2.041 149 150 299 Lkr. München 21 83 104 2.453 2.483 4.936 1.607 480 2.087 Lkr. Neuburg-Schrobenhausen 9 66 75 294 1.522 1.816 123 113 236 Lkr. -

Nuts-Map-DE.Pdf

GERMANY NUTS 2013 Code NUTS 1 NUTS 2 NUTS 3 DE1 BADEN-WÜRTTEMBERG DE11 Stuttgart DE111 Stuttgart, Stadtkreis DE112 Böblingen DE113 Esslingen DE114 Göppingen DE115 Ludwigsburg DE116 Rems-Murr-Kreis DE117 Heilbronn, Stadtkreis DE118 Heilbronn, Landkreis DE119 Hohenlohekreis DE11A Schwäbisch Hall DE11B Main-Tauber-Kreis DE11C Heidenheim DE11D Ostalbkreis DE12 Karlsruhe DE121 Baden-Baden, Stadtkreis DE122 Karlsruhe, Stadtkreis DE123 Karlsruhe, Landkreis DE124 Rastatt DE125 Heidelberg, Stadtkreis DE126 Mannheim, Stadtkreis DE127 Neckar-Odenwald-Kreis DE128 Rhein-Neckar-Kreis DE129 Pforzheim, Stadtkreis DE12A Calw DE12B Enzkreis DE12C Freudenstadt DE13 Freiburg DE131 Freiburg im Breisgau, Stadtkreis DE132 Breisgau-Hochschwarzwald DE133 Emmendingen DE134 Ortenaukreis DE135 Rottweil DE136 Schwarzwald-Baar-Kreis DE137 Tuttlingen DE138 Konstanz DE139 Lörrach DE13A Waldshut DE14 Tübingen DE141 Reutlingen DE142 Tübingen, Landkreis DE143 Zollernalbkreis DE144 Ulm, Stadtkreis DE145 Alb-Donau-Kreis DE146 Biberach DE147 Bodenseekreis DE148 Ravensburg DE149 Sigmaringen DE2 BAYERN DE21 Oberbayern DE211 Ingolstadt, Kreisfreie Stadt DE212 München, Kreisfreie Stadt DE213 Rosenheim, Kreisfreie Stadt DE214 Altötting DE215 Berchtesgadener Land DE216 Bad Tölz-Wolfratshausen DE217 Dachau DE218 Ebersberg DE219 Eichstätt DE21A Erding DE21B Freising DE21C Fürstenfeldbruck DE21D Garmisch-Partenkirchen DE21E Landsberg am Lech DE21F Miesbach DE21G Mühldorf a. Inn DE21H München, Landkreis DE21I Neuburg-Schrobenhausen DE21J Pfaffenhofen a. d. Ilm DE21K Rosenheim, Landkreis DE21L Starnberg DE21M Traunstein DE21N Weilheim-Schongau DE22 Niederbayern DE221 Landshut, Kreisfreie Stadt DE222 Passau, Kreisfreie Stadt DE223 Straubing, Kreisfreie Stadt DE224 Deggendorf DE225 Freyung-Grafenau DE226 Kelheim DE227 Landshut, Landkreis DE228 Passau, Landkreis DE229 Regen DE22A Rottal-Inn DE22B Straubing-Bogen DE22C Dingolfing-Landau DE23 Oberpfalz DE231 Amberg, Kreisfreie Stadt DE232 Regensburg, Kreisfreie Stadt DE233 Weiden i. -

Exposé Reit Im Winkl

BAYERISCHE STAATSFORSTEN • AöR Telefon +49-8663-8887-0 Forstbetrieb Ruhpolding Telefax +49-8663-8887-20 [email protected] • www.baysf.de Exposé ehemaliges Forsthaus Weitseestraße 48, 83242 Reit im Winkl Mit der Verwertung dieses Grundstücks ist betraut: Mit der Vermarktung dieses Objektes betraut ist: Forstbetrieb Ruhpolding Zellerstraße 10 83324 Ruhpolding Herr Josef Kreuz Tel.: 08663 – 8887-0 Fax: 08663 – 8887-20 [email protected] Bayerische Staatsforsten AöR – Forstbetrieb Ruhpolding Zellerstraße 10, 83324 Ruhpolding Seite 1 von 16 BAYERISCHE STAATSFORSTEN • AöR Telefon +49-8663-8887-0 Forstbetrieb Ruhpolding Telefax +49-8663-8887-20 [email protected] • www.baysf.de 83242 Reit im Winkl, Weitseestraße 48 Ehem. Forstamtsanwesen Objektart: Freistehendes Wohnhaus mit Nebengebäuden Grundstück: FlNr. 818, Gemarkung Reit im Winkl zu 1.960 m² Grundbuchstand: Keine Belastung Grundstücks- und Gebäudebeschreibung: Bebauung: Wohngebäude, Gebäude- und Freifläche Planungs- und Liegt nicht im Geltungsbereich eines Baurecht: Bebauungsplans. Erschließung: Erfolgt bisher über das Nachbargrundstück FlNr. 121/11, Gemarkung Reit im Winkl Baujahr des Gebäudes: 1925 Denkmalschutz: nein Die Vergabe des Grundstücks erfolgt im Wege eines Erbbaurechts. Schriftliche Angebote werden bis zum 21.05.2021 um 12:00 Uhr in einem verschlossenen Kuvert mit dem Stichwort „Gebot Reit im Winkl“ erbeten. Objektbesichtigung nach telefonischer Vereinbarung. Ansprechpartner: Herr Josef Kreuz Tel.: 08663 – 8887 -0 Bayerische Staatsforsten AöR – Forstbetrieb Ruhpolding Zellerstraße 10, 83324 Ruhpolding Seite 2 von 16 BAYERISCHE STAATSFORSTEN • AöR Telefon +49-8663-8887-0 Forstbetrieb Ruhpolding Telefax +49-8663-8887-20 [email protected] • www.baysf.de 1. Standort 1.1 Makrolage Bundesland Bayern Regierungsbezirk Oberbayern Gemeinde Reit im Winkl, ca. 2.300 Einwohner Nächstgelegene Orte Kössen (Österreich), ca. -

Kathrein Mobile Communication – Now Part of Ericsson

Ericsson Antenna Technology Germany GmbH • Klepperstraße 26 • 83026 Rosenheim • Germany Ericsson Antenna Technology Germany GmbH Klepperstraße 26 83026 Rosenheim Kathrein Mobile Germany Phone: +49 8031 184-0 Fax: +49 8031 184-306 Communication www.kathrein.com Company Responsible: – now part of Markus Feld VAT Reg. No.: DE 324 954 029 Tax ID No.: 103/5725/3930 Ericsson BNP Paribas IBAN: NL05 BNPA 0227 7141 56 BIC: BNPANL2AXXX Zum 1. Oktober 2019 ist die Kathrein Mobile Communication die Ericsson Antenna Technology Germany GmbH (im Folgenden auch „EAG“), eine mit Gesellschaftsvertrag vom 16. Januar 2019 neu gegründete Gesellschaft mit beschränkter Haftung (GmbH) nach deutschem Recht mit Sitz in Rosenheim (Geschäftsanschrift: Prinzenallee 21, 40549 Düsseldorf). EAG ist im Handelsregister B des Amtsgerichts Traunstein unter der Nr. HRB 27988 eingetragen und hat ein Stammkapital von derzeit EUR 2.000.000,00. EAG wird vertreten durch den Geschäftsführer Markus Feld. Alleinige Gesellschafterin von EAG ist die Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson (publ), eine börsennotierte Aktiengesellschaft nach schwedischem Recht. Die neuen Firmendaten lauten seither wie folgt: Ericsson Antenna Technology Germany GmbH Klepperstraße 26 83026 Rosenheim, Germany UST-Ident-Nr: DE 324 954 029 Steuer-Nr.: 103/5725/3930 As of 1 October 2019, Kathrein Mobile Communication is Ericsson Antenna Technology Germany GmbH (hereinafter also referred to as “EAG”), a limited liability company under German law, newly established by articles of association dated 16 January 2019, with its head office in Rosenheim (business address: Prinzenallee 21, 40549 Düsseldorf, Germany). EAG is registered in the commercial register, section B, of Amtsgericht Traunstein (district court Traunstein) under the number HRB 27988 and has a share capital of currently EUR 2,000,000. -

OECD Territorial Grids

BETTER POLICIES FOR BETTER LIVES DES POLITIQUES MEILLEURES POUR UNE VIE MEILLEURE OECD Territorial grids August 2021 OECD Centre for Entrepreneurship, SMEs, Regions and Cities Contact: [email protected] 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 3 Territorial level classification ...................................................................................................................... 3 Map sources ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Map symbols ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Disclaimers .................................................................................................................................................. 4 Australia / Australie ..................................................................................................................................... 6 Austria / Autriche ......................................................................................................................................... 7 Belgium / Belgique ...................................................................................................................................... 9 Canada ......................................................................................................................................................