Southern Jewish History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Passover Menu

Salt Lake City, Utah 84123 Salt Lake City, 4641 South Cherry Street & SPECIAL EVENTS CATERING CUISINE UNLIMITED CUISINE UNLIMITED CATERING & SPECIAL EVENTS Cuisine Unlimited invites you to experience the traditions of our international cuisine. Our philosophy is to offer our clients innovative, custom-designed menus, artistically presented CUISINE UNLIMITED and professionally served. Bestow upon your CATERING & SPECIAL EVENTS family, friends and colleagues the excellence we offer with over thirty years of experience in corporate and social catering. 2016 PASSOVER 4641 South Cherry Street Salt Lake City, Utah 84123 MENU 801.268.2332 Salt Lake City 435.647.0010 Park City 888.578.0763 Toll Free Celebrate with Family and Friends 801.268.2992 Fax www.cuisineunlimited.com FOR THE SEDER ENTREES DESSERTS Haroset $8.50 lb. Herb-Roasted Chicken Breasts $6.50 ea. Chocolate Flourless Torte $45.00 ea. Gefilte Fish – large $6.50 ea. Apple-Almond Stuffed Chicken $8.50 ea. (serves 12-14) Salmon with Lemon Sauce $8.50 pp. Traditional Brisket $11.50 pp. Chocolate Orange Torte $45.00 ea. Roasted Eggs $1.00 ea. Whole Roasted Turkey (18-22 lb.) $125.00 ea. (serves 12-14) Lamb Shank $3.50 ea. Roast Leg Lamb $18.50 lb. Passover Chocolate Mousse Cake $45.00 ea. Matzah-Meat Pie (serves 10-12) $45.00 ea. (serves 10) Matzah-Potato & Spinach Pie $45.00 ea. Sponge Cake (serves 8-10) $22.50 ea. HORS D’OEUVRES (serves 10-12) Chocolate Brownies $2.75 ea. (minimum 8 servings/3lbs.) Macaroons $1.50 ea. SIDE DISHES Passover Mandelbrot $2.50 ea. -

YOM KIPPUR 2015 YOM KIPPUR 2015 * New Item V Vegetarian N Contains Nuts GF Gluten Free

YOM KIPPUR 2015 YOM KIPPUR 2015 * New Item V Vegetarian N Contains Nuts GF Gluten Free THE “BREAK THE FAST” PACKAGE No substitutions or deletions. In disposable containers except where noted. Package orders are available for 10 or more people in multiples of 5 thereafter. All “choice” items may be divided in multiples of 10 only. ALL PACKAGES INCLUDE Traditional creamy white albacore tuna salad. GF Nancy’s Noodle Kugel with corn flake and cinnamon topping. May also be ordered without raisins. V Fresh sliced fruit. V | GF SELECT A BASKET THE BEST SMOKED FISH BASKET 28.95/pp New York’s finest nova smoked salmon. Rolled. GF Smoked whitefish filet and peppered sable. Taster portion. GF Freshly baked assortment of “New York” bagels and bialys. 2 per person. Whipped plain and chive cream cheese. GF Sliced muenster, cheddar and swiss. Sliced tomato, shaved bermuda onion, seedless cucumber and mediterranean black olives. GF or NOVA LOX BASKET The Best Smoked Fish Basket without the smoked whitefish and peppered sable. 23.75/pp New York’s finest nova smoked salmon. Rolled. GF Freshly baked assortment of “New York” bagels and bialys. 2 per person. Whipped plain and chive cream cheese. GF Sliced muenster, cheddar and swiss. Sliced tomato, shaved bermuda onion, seedless cucumber and mediterranean black olives. GF or DELI BASKET 27.95/pp Eisenberg first-cut corned beef (50%), oven roasted turkey breast (30%), and sirloin (20%). Sliced cheddar and swiss cheese. Lettuce, tomato, pickle, red onion and black olives, mustard and mayonnaise. Freshly baked french onion rolls, old fashioned rolls, and light and dark rye. -

Kamus Bahasa Melayu-Inggeris (1/2)

mengabdikan: to enslave pengabdian: slavery; enslavement acu Kamus Bahasa Melayu-Inggeris (1/2) to direct weapon at target abjad http://dictionary.bhanot.net/ alphabet mengacukan: to aim weapon at target mengacu: to test; to try on A acuan: a mould abu abad ash century acuh mengabui: to cheat; to deceive to care for; to heed berabad-abad: for centuries mengacuhkan: to care for; to heed acuh tak acuh: to show indifference abuk abadi dust eternal; immortal acum keabadian: immortality provoke or instigate mengabadikan: perpetuate; immortalize abung pomelo mengacum: to provoke or instigate acuman: provocation pengacum: instigator pengacuman: agitation abah father acah tease mengacah-acah: to tease ada have; possess; contain abah-abah harness adakala: sometimes adakalanya: sometimes acapkali adalah: is; are; am; was; were often adapun: with regard to abai berada: (1) rich (2) to be neglect diadakan: to be held keadaan: condition; situation; circumstances mengabaikan: to disregard; to neglect acar mengada-ngada: to boast; to pretend pickle mengada-ngadakan: to concoct an excuse mengadakan: to hold or conduct; to convene abang elder brother acara event; item in a programme adab abang angkat: foster brother politeness; good manners; courtesy abang ipar: brother-in-law mengacarakan: to compere or host a programme abang tiri: stepbrother pengacara: master of ceremonies; compere beradab: courteous; polite peradaban: civilization; culture abdi aci slave shaft adang obstruct; block Bahasa Melayu 24.02.2007 http://mementoslangues.com/ Kamus Bahasa -

Sandwiches Corned Beef Pastrami Reuben

Downtown Indianapolis 808 S. Meridian Street Indianapolis, IN 46225 Ph. 317-631-4041 Fax. 317-631-3958 Mon-Sun 6:30am-8pm Sandwiches Half sandwiches# available for Corned Beef $14.25 many choices. Ask which ones! Pastrami $14.70 Reuben (Sauerkraut) $15.10 Bread Shapiro’s Famous NY Reuben (Cole Slaw) $15.10 Hand Cut Rye, Sourdough, Beef Brisket $14.25 Gluten Free, Wheat, White, Peppered Beef $14.25 Marble Rye, Pumpernickel, Rare Roast Beef $14.25 Onion Bun, Egg Bun, Smoked Tongue $14.70 Poppy Seed Hot Dog Bun, P. L. T. $ 7.25 Bagel +80¢, Croissant+$1.35 Kosher Style Frank $ 5.00 Cheese +70¢ Pure Beef Burger $ 5.00 Swiss, Muenster, Provolone, Salami $ 6.50 Colby-Jack, American Chopped Liver $ 8.00 Extra Stuff Bologna $ 6.00 Chopped Liver Schmear $2.55 Roasted/Smoked Turkey $ 9.25 & Things Free Chicken Salad $ 9.15 Tomato, Lettuce, Onion, Albacore Tuna Salad $ 9.15 Mustards—Spicy Brown or Grilled Cheese $ 6.35 Yellow, Ketchup, Alaska Pollock Beer Battered $ 7.90 (Fri till 4pm) Mayonnaise (if you must…) Still out of Ham # 1/2 Sandwich & Cup Soup $9.80 Soups Salad & Platters Vegetable Soup Daily Daily Tossed Salad $ 3.85 Chicken Noodle Soup Chicken Broth Daily Greek Salad $ 6.35 Daily Chef Salad Matzo Ball $ 8.45 Cabbage Borscht Daily California Chopped $ 8.45 Beef Stew (not Sunday) Daily Salmon Salad $ 8.45 Chili (until 4pm, Seasonal) Daily Chicken Caesar Salad $ 7.90 Bean Soup Mon. Chicken Salad Platter $11.25 Chicken Stew T., Th. Albacore Tuna Platter $11.25 Lentil Soup Tues. -

Meat & Pareve Appetizer Platter Selections

MEAT & PAREVE APPETIZER PLATTER SELECTIONS Enjoy our appetizer platters as an accompaniment to evening cocktails or as a refreshment break for a working meeting. As a guideline our small platters serve 10-12 guests and the large platters serve 16-20 guests. Serving utensils accompany all orders. Disposable plates and utensils are available at an additional charge. DELICIOUS COLD OR AT ROOM TEMPERATURE Vegetable Crudités Baskets of seasonal vegetables including cauliflower, carrot sticks, strips of red & green peppers, cherry tomatoes, baby squash and zucchini served with assorted dips Small – 4lbs. 49.95 Large – 6lbs. 64.95 Grilled Vegetables Please let us know whether you prefer a plattered arrangement of miniature skewers Lightly brushed with olive oil and then put on the grill - eggplant, zucchini, plum tomatoes, onions, yellow squash, red & green peppers and portabella mushrooms served with crostini Your choice of vegetables arranged on a platter or served on miniature skewers By the Platter Small – 4lbs. 49.95 Large – 6lbs. 64.95 By the Skewer Small with 35 skewers 55.95 Large with 50 skewers 69.95 Sushi! Made fresh to order by our in-house Sushi Chef. Each platter includes an assortment of Tekka Maki (tuna), Salmon Maki, California Rolls and Veggie Maki. Accompanied by pickled ginger, soy, wasabi and chopsticks. Small platter with 48 pieces – 44.95 and Large platter with 72 pieces – 64.95 Bruschetta with Assorted Tapenades Crispy crostini topped with a tapenade medley of sun-dried tomato, black olive & white bean Platter with 60 pieces – 64.95 Assorted Pinwheel Wraps Enjoy an assortment of pinwheel wraps including roast beef, grilled vegetables and turkey Small with 36 pieces - 39.95 Large with 60 pieces - 59.95 Mediterranean Salads with Pita 1. -

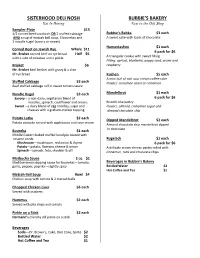

Bubbie's Bakery

SISTERHOOD DELI NOSH BUBBIE’S BAKERY Eat In Dining Next to the Gift Shop Sampler Plate $15 1/2 corned beef sandwich OR 2 stuffed cabbage Bubbie’s Babka $3 each AND a cup of matzah ball soup, 3 bourekas and A sweet cake with loads of chocolate 1 noodle kugel (savory or sweet) Hamantashen $1 each Corned Beef on Jewish Rye Whole $11 6 pack for $6 Mr. Brisket corned beef on rye bread Half $6 A triangular cookie with sweet filling with a side of coleslaw and a pickle Filling: apricot, blueberry, poppy seed, prune and Brisket $6 raspberry Mr. Brisket beef brisket with gravy & a slice of rye bread Kuchen $5 each A mini loaf of rich sour cream coffee cake Stuffed Cabbage $3 each Flavors: cinnamon raisin or cinnamon Beef stuffed cabbage roll in sweet tomato sauce Noodle Kugel $3 each Mandelbrot $1 each Savory – a non-dairy, vegetarian blend of 6 pack for $6 noodles, spinach, cauliflower and onions Biscotti-like pastry Sweet – a dairy blend of egg noodles, sugar and Flavors: almond, cinnamon sugar and cheeses with a graham cracker topping almond chocolate chip Potato Latke $2 each Dipped Mandelbrot $2 each Potato pancake served with applesauce and sour cream Almond chocolate chip mandelbrot dipped Boureka $1 each in chocolate Middle Eastern baked stuffed hand pie coated with sesame seeds Rugelach $1 each Mushroom—mushroom, red onion & thyme 6 pack for $6 Potato—potato, Romano cheese & onion A delicate cream cheese pastry rolled with Spinach—spinach, feta, cheddar & dill cinnamon, nuts and chocolate chips Matbucha Sauce 2 oz. -

Simcha Brunch Menu Minimum 20 Guests Available As a Drop-Off Or Staffed Event

Simcha Brunch Menu Minimum 20 Guests Available as a drop-off or staffed event Menu One $18.00 per Person Mixed Miniature Bagels with an Assortment of Miniature Muffins and Danish Served with Butter, Jams and assorted Cream Cheese Platter of Smoked Salmon & Whitefish Salad served with Sliced Tomatoes and Lemon Mixed Greens with Tomatoes & Mushrooms Sliced Fresh Seasonal Fruit Platter Orange Juice & Bottled Water Menu Two $25.00 per Person Mixed Miniature Bagels with an Assortment of Miniature Muffins and Danish Served with Butter, Jams and assorted Cream Cheese Platter of Smoked Salmon & Whitefish Salad served with Sliced Tomatoes and Lemon Mixed Greens with Tomatoes & Mushrooms Choice of Homemade Broccoli or Mushroom Quiche Flaky Filo Pastry Borekas filled with Potato & Mushroom Sliced Fresh Seasonal Fruit Platter Orange Juice & Bottled Water Menu Three $30.00 per Person Mixed Miniature Bagels with an Assortment of Miniature Muffins and Danish Served with Butter, Jams and assorted Cream Cheese Platter of Smoked Salmon & Whitefish Salad served with Sliced Tomatoes and Lemon Mixed Greens with Tomatoes & Mushrooms Choice of Homemade Broccoli or Mushroom Quiche Flaky Filo Pastry Borekas filled with Potato & Mushroom Choice of Hot Entrée Scrambled Eggs, Omelet or French Toast Served with Hash Browned Potatoes Sliced Fresh Seasonal Fruit Platter Orange Juice & Bottled Water 216 E. 49th Street, 2nd floor, New York, NY 10017 212.207.3888 Cholev Israel DAIRY & PAREVE APPETIZER PLATTERS Enjoy our appetizer platters as an accompaniment to evening cocktails or as a refreshment break for a working meeting. As a guideline our small platters serve 10-12 guests and the large platters serve 16-20 guests. -

Rewriting the Haggadah: Judaism for Those Who Hold Food Close

Bard College Bard Digital Commons Senior Projects Spring 2020 Bard Undergraduate Senior Projects Spring 2020 Rewriting the Haggadah: Judaism for Those Who Hold Food Close Rose Noël Wax Bard College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2020 Part of the Food Studies Commons, Jewish Studies Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. Recommended Citation Wax, Rose Noël, "Rewriting the Haggadah: Judaism for Those Who Hold Food Close" (2020). Senior Projects Spring 2020. 176. https://digitalcommons.bard.edu/senproj_s2020/176 This Open Access work is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been provided to you by Bard College's Stevenson Library with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this work in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rewriting the Haggadah: Judaism for Those Who Hold Food Close Senior Project Submitted to The Division of Social Studies of Bard College by Rose Noël Wax Annandale-on-Hudson, New York May 2020 Acknowledgements Thank you to my parents for teaching me to be strong in my convictions. Thank you to all of the grandparents and great-grandparents I never knew for forging new identities in a country entirely foreign to them. -

Jewish Bakeries and Baked Goods in London and Berlin

Cultures in Transit Diaspora Identities: Jewish Bakeries and Baked Goods in London and Berlin DEVORAH ROMANEK This essay investigates how material culture acts as an agent of cultural construction when social and cultural practices are geographically displaced. It does this by taking a comparative look at current Jewish Diaspora communities in London and Berlin, and by analyzing the production, consumption and broader meaning of three Jewish baked goods – matzos, challah and bagels - in the context of Diaspora communities in these two cities. The comparison between London and Berlin also allows a consideration of the construction of ‘locality’/‘setting’, particularly in the transient sense of a fluid concept of sense-of-place as constructed against a backdrop of material culture; additionally, the level of religious observance; the contrast of notions of ‘fixed’ and ‘fluid’, and ‘traditional’ and ‘cosmopolitan’; and the agency of the baked goods themselves is observed and analyzed. Introduction Anthropological discussions on the theme of cultures in movement, that is to say Diaspora, or the more contemporary notions of globalization and transnationalism, offer many disparate theories. There is the argument that globalization as a post- modern phenomenon is bringing an end to the practice of ‘tradition’ and ‘traditional cultures’, and that it is inviting a worldwide culture of heterogeneity .1 1 For a discussion of this see Anthony Giddens, “Living in a post-traditional society”, in Ulrich Beck, Reflexive Modernization: Politics, Tradition and Aesthetics in the Modern Social Order, Cambridge, Polity Press, 1994. Diaspora Identities: Jewish Bakeries and Baked Goods in London and Berlin There is the counter-argument that the pressure or threat (perceived or real) felt by various communities and cultures against their ‘traditional’ ways has induced a counter-reaction, which is being expressed in renewed and intensified forms of nationalism, and increasingly more delineated and defined concepts of self and community. -

The Elegant Station Party

The Elegant Station Party Cold Displays Select 2 Lavishly Decorated Crudités Displays Freshly Cut Carrots, Celery, Cauliflower, Summer Squashes, Colored Peppers, Baby Corn & Ripe Olives, served with an assortment of Dips prepared by our Chefs: Honey Curry, Spinach Artichoke, Humus Displayed Flowing from Wicker Baskets in tiered Levels accented with Green, Purple & White Flowering Kale Eggplant Caponata Display Fresh Garlic, Onions & Eggplant Sautéed in Extra Virgin Olive Oil with Plum Tomatoes, Peppers, Mushrooms & Black Olives served in a Champagne Bucket with Lavish Crackers * Smoked Salmon Mosaic Finely Minced Norwegian Smoked Salmon, Towering Martini Glasses filled with Caviar, Egg Whites & Yellows, Red Onion & Fresh Parsley displayed on Cracked Italian Marble Palates and presented with triangles of Russian Pumpernickel & Exotic Flatbreads *Roasted Vegetable Turret & Tuscany Antipasto Layers of Fresh Roasted Vegetables: Eggplant, Squash, Portobello Mushrooms, Peppers & Zucchini Molded & Infused with a Balsamic Reduction, Red Peppers, Garlic Olives, Marinated Mushrooms, Artichoke Hearts Served with Garlic Toasted Baguette Rounds ** Tuna Carpaccio Peppered Sushi Grade Tuna pan seared to perfection, sliced & served over a Mountain of Japanese Seaweed Salad…excellent! Sesame Noodles and Gingered Scallions Delicious Cold Sesame Noodles displayed with an Oriental Towers & served in Chinese Food Containers with Chopsticks Spinach Leek Pie A delectable creation of warm Spinach & Mushrooms, Shallots & Leeks in Phyllo * Counts as 2 selections -

Drums & Flats Drums & Flats

Anderson North Campus - Menu Sunday Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday Friday Saturday 16-May 17-May 18-May 19-May 20-May 21-May 22-May Entrée Entrée Entrée Entrée Entrée Entrée Entrée Salmon Croquetts Rosemary Pork Loin Country Steak and Yellow Rice Fried Chicken Baked Cod Supreme Baked Chicken Baked Chicken Fried Chicken Baked Chicken Baked Chicken Meatloaf Spaghetti & Meatsauce Catfish w/Hushpuppies Lasagna Baked Chicken Chuckwagon Steak Blackened Fish Baked Chicken Baked Chicken Grilled Pork Chop Chopped Steak w/Onions Sides Sides Sides Sides Sides Sides Sides Broccoli Squash and Onions Rice Pilaf Blackeye Peas Macaroni & Cheese Broccoli w/ Cheese Sauce Macaroni & Cheese Mashed Potato /Gravy Parslied New Potatoes Macaroni & Cheese Turnip Greens Roasted Cauliflower Macaroni & Cheese Peas & Carrots Baby Lima Beans Collard Greens Cabbage Steamed Broccoli Corn Nuggets Turnip Greens Green Beans Macaroni & Cheese Macaroni & Cheese Whole Kernel Corn Fried Okra Baby Carrots Cheese Grits Broccoli Steamed Broccoli Steamed Broccoli Mashed Potatoes/Gravy Mustard Greens Baby Lima Beans Rice and gravy Exhibition Station Exhibition Station Exhibition Station Exhibition Station Exhibition Station Exhibition Station Fried Chicken Tender Shrimp and Cheese Grits Chicken Quesadillia and Drums & Wrap w/Fries 24oz Grilled Garlic Bread w/24oz Fries w/24oz Fountain Fountain or 20oz Bottle Fountain or 20oz Bottle Soda or 20oz Bottle Soda Flats Grill Grill Grill Grill Grill Maple Bacon Patty Melt Chicken Tenders on a Chili Dogs/French Fries Bacon-Ranch-Chicken Beef Taco Salad, Salsa, w/Fries/24oz Fountain Croissant w/Fries/24oz w/24oz Fountain Drink Salad w/24oz Fountain Sour Cream w/24oz or 20oz Bottle Fountain or 20oz Bottle or 20oz Bottle Drink or 20oz Bottle24oz Fountain Drink or 20oz Bottle Philly Cheesesteak w/ drumsFries 24oz Fountain & flats Drink--- ain'tor 20oz not thang Bottle but a chicken wang--- what's your style _______________ top it off _______________ choose your side . -

Adaptation, Immigration, and Identity: the Tensions of American Jewish Food Culture by Mariauna Moss Honors Thesis History Depa

Adaptation, Immigration, and Identity: The Tensions of American Jewish Food Culture By Mariauna Moss Honors Thesis History Department University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 03/01/2016 Approved: _______________________ Karen Auerbach: Advisor _______________________ Chad Bryant: Advisor Table of Contents Acknowledgements Introduction 4 Chapter 1 12 Preparation: The Making of American Jewish Food Culture Chapter 2 31 Consumption: The Impact of Migration on Holocaust Survivor Food Culture Chapter 3 48 Interpretation: The Impact of the Holocaust on American-Jewish Food Culture Conclusion 66 2 Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my correspondents, Jay Ipson, Esther Lederman, and Kaja Finkler. Without each of your willingness to invite me into your homes and share your stories, this thesis would not have been possible. Kaja, I thank you especially for your continued support and guidance. Next, I want to give a shout-out to my family and friends, especially my fellow thesis writers, who listened to me talk about my thesis constantly and without a doubt saw the bulk of my negative stress reactions. Thank you all for being such a great support system. It is my hope that at least one of you will read this- here’s looking at you, Mom. Third, I would like to thank Professor Waterhouse for sticking with me throughout this entire process. I could not have done this without your constant kind words and encouragement (though I could have done without your negative commentary about Billy Joel). Thank you for making this possible. Finally, I extend the largest thank you to my wonderful thesis advisors, Professor Karen Auerbach and Professor Chad Bryant.