Vaccination in Halakhah and in Practice in the Orthodox Jewish Community

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Print Ki Tisa

S E P H A R D I C Family, Business, & Jewish Life Through the Prism of Halacha VOLUME 5779 • ISSUE XXI • PARASHAT KI TISA • A PUBLICATION OF THE SEPHARDIC HALACHA CENTER policyholder is giving money to the partnership, STATE OF which includes other Jews, in exchange for the promise of a return with interest? and THE UNION, In my opinion, this is not a problem at all. Since every policyholder receives equal treatment, REVISITED none of them is lending to another. Were the company to go bankrupt, no policyholder would personally have to pay any other policyholder. Summary of Parasha & Halacha Shiur on Ki Tissa by Rav Yehoshua Sova The promised rate of return is nothing more Adapted from a Shiur by Rav Shmuel Honigwachs than the company declaring that it is doing so Distracted by Design: How to stay Our recent article following the Kol Kore well and on such strong financial footing that focused in our Tefillah? (rabbinic proclamation) on credit unions the cash value of each policyholder’s stake will In this Parasha we read about the sin of the (“State of the Union: May One Join PenFed certainly increase by that amount. I presented golden calf. This sin was caused by a disconnect or First Atlantic?”) prompted many questions between the Jews and Hashem, as the Gemara from readers about other entities with similar this argument to Rav Shlomo Miller shlit”a and structures to credit unions, particularly mu- he concurred. compares this to a bride leaving her Huppah for tual whole life insurance companies. -

Nitzotzot Min Haner Volume #16 January – March 2004 -- Page # 2

NNiittzzoottzzoott MMiinn HHaaNNeerr VVoolluummee ##1166,, JJaannuuaarryy –– MMaarrcchh 22000044 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW 2 MYSTERIOUS APPEARANCE OF THE COMMUNITY KOLLEL IDEA 3 MODELS 8 THE KOLLEL AS AN OUTREACH ORGANIZATION 10 HALACHIC STANDARDS 13 THE KOLLEL AS A CATALYST FOR OTHER INSTITUTIONS IN THE CITY 15 THE KOLLEL AS A SPRINGBOARD FOR NEW MANPOWER IN THE COMMUNITY 16 THE KIRUV CONTRIBUTION OF THE LAKEWOOD-TYPE COMMUNITY KOLLEL 18 THE PERCEPTION OF KOLLEL FAMILIES BY THE COMMUNITY 20 WHY KOLLELS FAILED? 21 IS A KOLLEL ALWAYS GOOD FOR A TOWN? 22 HOW TO START A NEW KOLLEL 25 FINANCES 25 SIZE 26 KOLLEL SALARIES 26 LOCAL INTEREST AND SUPPORT 26 COMMUNITY OR OUTREACH MODEL 27 SELECTION OF THE ROSH CHABURA 27 SELECTION OF THE AVREICHIM 28 ADVANCE GUARD AND WELCOMING COMMITTEE 30 Appendices APPENDIX A: WHAT SHOULD BE CALLED A KOLLEL? 32 APPENDIX B: THE TORAH STUDY OF THE AVREICHIM 33 APPENDIX C: THE CHICAGO COMMUNITY KOLLEL - LIST OF ALUMNI 35 Nitzotzot Min HaNer Volume #16 January – March 2004 -- Page # 2 Introduction and Overview A Jewish man without torah knowledge Is a man divorced from his glorious past; A Jewish city without halls of torah study Is a city estranged from its glorious future. Rabbi Zev Epstein1 on the idea of a kollel In every way Kollel rabbis are ambassadors of Torah … A Rav without a defined kehilla … A bridge so to speak to the Torah world Rabbi Zvi Holland, Phoenix Community Kollel In this edition, Nitzotzot has undertaken a discussion of the central institution in the development of Torah life around the world, the community or outreach kollel. -

Mez.Iz.Ah Be-Peh―Therapeutic Touch Or Hippocratic Vestige?1

15 Meziẓ aḥ be-Peh―Therapeutic Touch or Hippocratic Vestige? 1 By: SHLOMO SPRECHER With the appearance of a news article in the mass-circulation New York Daily News2 implicating meziẓ aḥ be-peh3 in the death of a Brooklyn 1 The author wishes to emphasize that he subscribes fully to the principle that an individual’s halakhic practice should be determined solely by that individual’s posek. Articles of this nature should never be utilized as a basis for changing one’s minhag. This work is intended primarily to provide some historical background. It may also be used by those individuals whose poskim mandate use of a tube instead of direct oral contact for the performance of meziẓ aḥ , but are still seeking additional material to establish the halakhic bona fides of this ruling. Furthermore, the author affirms that the entire article is predicated only on “Da’at Ba’alei Battim.” 2 February 2, 2005, p. 7. 3 I am aware that purists of Hebrew will insist that the correct vocalization should be be-feh. However, since all spoken references I’ve heard, and all the published material I’ve read, use the form “be-peh,” I too will follow their lead. I believe that a credible explanation for this substitution is a desire to avoid the pejorative sense of the correct vocalization. Lest the reader think that Hebrew vocalization is never influenced by such aesthetic considerations, I can supply proof to the contrary. The Barukh she-’Amar prayer found in Tefillat Shahariṭ contains the phrase “be-feh ‘Amo.” Even a novice Hebraist can recognize that the correct formulation should be in the construct state―“be-fi ‘Amo.” Although many have questioned this apparent error, Rabbi Yitzchak Luria’s supposed endorsement of this nusah ̣ has successfully parried any attempts to bring it into conformity with the established rules of Hebrew grammar. -

Tz7-Sample-Corona II.Indd

the lax family special edition Halachic Perspectives on the Coronavirus II נקודת מבט על נגיף הקורונה ב׳ Tzurba M’Rabanan First English Edition, 2020 Volume 7 Excerpt – Coronavirus II Mizrachi Press 54 King George Street, PO Box 7720, Jerusalem 9107602, Israel www.mizrachi.org © 2020 All rights reserved Written and compiled by Rav Benzion Algazi Translation by Rav Eli Ozarowski, Rav Yonatan Kohn and Rav Doron Podlashuk (Director, Manhigut Toranit) Essays by the Selwyn and Ros Smith & Family – Manhigut Toranit participants and graduates: Rav Otniel Fendel, Rav Jonathan Gilbert, Rav Avichai Goodman, Rav Joel Kenigsberg, Rav Sam Millunchick, Rav Doron Podlashuk, Rav Bentzion Shor General Editor and Author of ‘Additions of the English Editors’: Rav Eli Ozarowski Board of Trustees, Tzurba M’Rabanan English Series: Jeff Kupferberg (Chairman), Rav Benzion Algazi, Rav Doron Perez, Rav Doron Podlashuk, Ilan Chasen, Adam Goodvach, Darren Platzky Creative Director: Jonny Lipczer Design and Typesetting: Daniel Safran With thanks to Sefaria for some of the English translations, including those from the William Davidson digital edition of the Koren Noé Talmud, with commentary by Rabbi Adin Even-Israel Steinsaltz www.tzurba.com www.tzurbaolami.com Halachic Perspectives on the Coronavirus II נקודת מבט על נגיף הקורונה ב׳ Introduction “Porch” and Outdoor Minyanim During Coronavirus Restrictions Responding to a Minyan Seen or Heard Online Making a Minyan Using Online Platforms Differences in the Tefilla When Davening Alone Other Halachot Related to Tefilla At Home dedicated in loving memory of our dear sons and brothers יונתן טוביה ז״ל Jonathan Theodore Lax z”l איתן אליעזר ז״ל Ethan James Lax z”l תנצב״ה marsha and michael lax amanda and akiva blumenthal rebecca and rami laifer 5 · נקודות מבט הלכתיות על נגיף הקורונה ב׳ צורבא מרבנן Introduction In the first shiur concerning the coronavirus, we discussed some of the halachic sources relating to the proper responses, both physical and spiritual, to an epidemic or pandemic. -

Cheshvan 5780

THE KOLLEL ACCLIMATES By Rabbi Baruch Weiss We had the privilege of speaking with another four members of the Kollel’s original nine yungerleit; Rav Mendel Nojowitz, Rav Gershon Eisenberger, Rav Boruch Kupfer, and Rav Zvi Horowitz. HaRav Elya Svei, Zt”l Kollel. During those visits, the yungeleit would often visit the Urman home on Palm drive and consult with It should be noted that Moreinu Rabbi Yaa- him about chinuch, halacha, and hashkafa. kov Michoel Hirschman, as well as a number of the original yungeleit, have expressed the Rabbi Kupfer related the following incident in which he received hadracha from HaRav Yaakov. Af- sentiment, that were it not for the encourage- ter learning with the Kollel for two years, Rabbi Kup- ment and backing of the Philadelphia Rosh Ye- fer decided to begin to help with the Kollel’s fundrais- shiva, HaRav Elya Svei, the Kollel would not ing. While developing financial relationships with the have been able to launch when it did. Most of community of shomrei Torah u’mitzvos continued the original nine yungeleit were his talmidim, to be handled by Moreinu HaRav Yaakov Michoel and a number of them consulted with him be- Hirschman, Rabbi Kupfer set his sights on those who fore deciding to come. were not yet Torah observant. Approaching successful businessmen who unfortunately had little knowledge Rabbi Mendel Nojowitz related, that orig- Harav Elya Svei zt”l about Torah and yiddishkeit, Rabbi Kupfer would talk inally, he was ambivalent about leaving Lake- to them about the need for Torah education in order to wood and participating in this new venture. -

Irgun Shiurai Torah

בס"ד IRGUN SHIURAI TORAH presents the ORLDWIDE SHOVAVIM PROJEC Worldwide Taharas Hamishpacha/Family Purity Review Courses during the sacred weeks of Shovavim rd JOIN THOUSANDS WORLDWIDE! LISTING Review the fundamental Halachos and Hashkafos that preserve the sanctity of the Jewish home! 3 These courses review the basic Halacha and Hashkafa issues that affect the daily lives of all observant family couples. Following is a partial listing of locations in the USA and Canada where review courses will take place. (Listed by state) ALL MARRIED Los Angeles, CA Mrs. Zehava Lefkowitz Fair Lawn, NJ Bais Mordechai D’Bertch • 3302 Ave P FOR WOMEN Bensalem, PA Khal Toras Emes • 1 Viewmount FOR MEN PEOPLE FOR MEN Khal Ahavas Yisroel Tzemach Tzedek FOR WOMEN Reb. Avigail Shalieh-Saboo FOR WOMEN Rabbi Kalman Ochs 6811 Park Heights Ave. Rabbi Tzvi Elimelech Rokeach Home of Mrs. Esther Soleimani Rabbi Ezra Douek Reb. Shevi Yudin 215 Grist Mill Lane Mrs. Rochel Goldbaum Hashkafa: Motzei Shabbos ARE INVITED! Cong. Hazon Ovadia • 7210 Beverly Blvd. Cong. Shomrei Torah • 19-10 Morlot Ave. Sun, Jan 17, 24 Bensalem Outreach Center • 2446 Bristol Rd. Mon, Jan. 25, Wed, Feb. 3 9:00-10:00 pm Maariv at 8:45, 10:00 Wed, Jan. 6, 13, 20, 27, Feb. 3 After Maariv Wed, Dec. 30, Jan. 6, 13, 20, 27, 8:00-9:00 PM Tues, Jan. 12 at 8:00 PM at 10:00 AM Sun, Feb. 21 at 7:00 PM Halacha: Thurs, Jan. 28, Feb. 4 Feb. 3 at 8:30 PM Halacha FOR WOMEN Scranton, PA at 8:30 pm Irgun Shiurai Torah Silver Spring, MD FOR WOMEN Riverdale, NY Reb. -

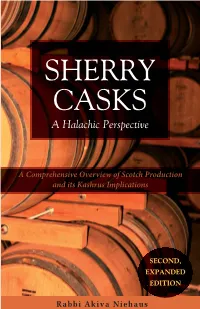

SHERRY CASKS a Halachic Perspective

SHERRY CASKS A Halachic Perspective A Comprehensive Overview of Scotch Production and its Kashrus Implications SECOND, EXPANDED EDITION Rabbi Akiva Niehaus SHERRY CASKS A Halachic Perspective A Comprehensive Overview of Scotch Production and its Kashrus Implications Rabbi Akiva Niehaus Chicago Community Kollel Reviewed by Rabbi Dovid Zucker, Rosh Kollel Published by the Chicago Community Kollel Adar 5772 / March 2012 Second, Expanded Edition Copyright © 2012 Rabbi Akiva Niehaus Chicago Community Kollel 6506 N. California Ave. Chicago, IL 60645 (773)262-9400 First Edition: June 2010 Second, Expanded Edition: March 2012 Questions and Comments or to request an accompanying PowerPoint: (773)338-0849 [email protected] 6506 N. California Ave. Chicago, IL 60645 (773) 262-4000 Fax (773) 262-7866 e-mail: [email protected] http://www.cckollel.org Haskamah from Rabbi Akiva Osher Padwa, Senior Rabbinical Coordinator & Director of Certification, London Beis Din – Kashrus Division הרב עקיבא אשר פדווא Rabbi Akiva Padwa מומחה לעניני כשרות Kashrus Consultant & Coordinator פק״ק לונדון יצ״ו London UK בס״ד ר״ח כסליו תשע״ב לפ״ק, פה לונדון יצ״ו I consider it indeed an honor and a privilege to have been asked to give a Haskoma to this Kuntrus “Sherry Casks: A Halachic Perspective”. Having read the Kuntrus I found it to be Me’at Kamus but Rav Aichus. Much has been written over the last few decades about whisky, however many of the articles written were based on incorrect technical details that do not reflect the realities at the distilleries. Many others may be factually and technically correct, but do not relate in depth to Divrei HaPoskim Z”TL. -

In This Issue

Volume II, Number 1 Reviewed by: HaRav Yisroel Belsky, Shlita MarCheshvan 5762 bayis, and for whatever else you 1. The Gedolim’s Directive. Unlike the nations of the know He can help you with. PPleaselease Note: world, we are blessed to have the guidance of our Gedolim in all situations, in war and in peace, individually and collectively. Our Suggestion 3: You Can Con- The purpose of this Bul- Gedolim have guided us to say Tehillim Chapters 83, 130 and 142, trol Foreign Thoughts During letin is to alert the public daily. We must be vigilant in our recitation of these “k’pitlach”, Davening. regarding timely issues better even with kavana. Moreover, they have urged us to come to Hashem only requires of which raise serious shul on time and daven each word of the entire davening, in addition us that which we can accom- shailos, so that the in- to other matters. plish. If you had an opportu- Let us demonstrate our Emunas Chachomim by carefully nity to count a stack of $100 formed person can ask following the directives of our Gedolim on a daily basis. bills and could only keep them his Rav the right ques- if your count was accurate, tions. This Bulletin is not 2. Nine Practical Suggestions to Daven with Kavana. In would you allow other plans intended to provide the light of the Gedolim’s directive, it is imperative that we consistently or responsibilities to enter improve our daily Tefilos. As your mind at that time? answers to these issues. It Dovid Hamelech teaches us in is intended to heighten In This Issue Tehillim (147:10), “Lo beg- Suggestion 4: Recognize each member of our com- vuras hasus yechpatz… That You Are Standing Before munity’s awareness of im- 1. -

A Response to the BET Journal “Ask the Rabbi” Column on Techeiles

Ask Another Rabbi – A response to the BET Journal “Ask the Rabbi” column on techeiles By Rabbi Dovid Hojdai BET Journal published an “Ask the Rabbi” essay responding to the question, “What possible reasons are there to say not to wear techeiles? Let's say that Murex is not the chilazon, and we have some strings that have been dyed blue for no reason. What problem could there be in attaching those strings to my tzitzis?” Bet Journal format will only allow for a relatively brief response, which I will gear to the general reader.1 The question asked is a hypothetical, based on a flawed premise. Serious and knowledgeable people are not dying strings with Murex techeiles for “no reason.” They are doing so because of the overwhelming evidence from the world of reality that Murex was used for techeiles at the time of Chazal and the opinions of great poskim that this evidence translates into an opportunity to fulfill the mitzvah of techeiles for the first time in more than a thousand years. For more on this, see, for instance, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3k6TIbx2XKk and https://www.techeiles.org/library_main/has-techeiles-been-found/. See as well the excellent pamphlet, https://www.techeiles.org/harav-meir-halevi-hellman-levush-haaron/. The “Ask the Rabbi” article presents Murex techeiles as, at best, a safek. Those quoted in the “Ask the Rabbi” essay say it’s less than that, not even a safek. And, according to the essay, these Rabbis have “good answers,” showing that the evidence is not compelling at all. -

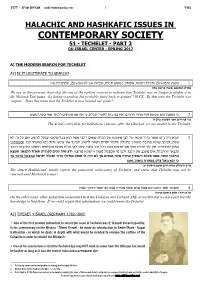

Techelet - Part 2 Ou Israel Center - Spring 2017

5777 - bpipn mdxa` [email protected] 1 c‡qa HALACHIC AND HASHKAFIC ISSUES IN CONTEMPORARY SOCIETY 51 - TECHELET - PART 2 OU ISRAEL CENTER - SPRING 2017 A] THE MODERN SEARCH FOR TECHELET A1] IS IT LEGITIMATE TO SEARCH? fpbp zlkzdy ,oal `l` epl oi` eiykre ,zlkz `edyk ?izni` .dyrie zlkze oal `iadl devn 1. gly zyxt (xaea) `negpz yxcn We saw in the previous shiur that the one of the earliest sources to indicate that Techelet was no longer available is in the Midrash Tanchuma. Its dating is unclear but probably dates back to around 750 CE. By that time the Techelet was ‘nignaz’. Does this mean that the Techelet is now beyond our grasp? `n`c dpia gen cr wx mibiyn ep` oi` ik ,zlkz lihdl gek epa oi` oaxegd ixg` dfd onfay `ed zn`d ik 2. 'd wxt zivivd xry miig ur ixt The Arizal writes that, for kabbalistic reasons, after the Churban, we are unable to use Techelet. `l df lk mre biydl lwpae mewn lka `ed ievn oalc meyn zlkz ly eypern oal ly eyper lecb xne` n"x did `ipz 3. epizeperae .oal xcrda enk lecb eyper oi` jkitl ,biydl dywe mixwi eincy zlkza k"`yn daexn eyper jkitl ,dyr xakc dpewzk devnd miniiwn epgp` n"ne oal eply zviv lke llk dfn mircei ep` oi`e zlkz epl oi` epxftzpy onfn `vny x`tzd cg`y zexetq mipy dfy rce .daexn eyper ef devn lhany in okle .oald z` akrn epi` zlkzdc x`azp cr xacd lhazpe l`xyi llkne xecd ilecbn rney el did `l j` miyp` dfi` eixg` jiynde zlkz epnn dyre oeflgd on` ,epinia dxdna wcv l`eb `ai ik ai sirq h oniq miig gxe` ogleyd jexr The Aruch Hashulchan1 totally rejects the purported rediscovery of Techelet2 and states that Techelet may not be renewed until Mashiach comes! ecevl oircei oi`y e` eze` oixikn oi`y `l` ievn `ed meid cry xyt`e 4. -

The Monthly Publication of the Young Israel of Hollywood - Ft

VOLUME 12, ISSUE 11 TAMUZ/AV 5780 / JULY/AUGUST 2020 EDITION THE MONTHLY PUBLICATION OF THE YOUNG ISRAEL OF HOLLYWOOD - FT. LAUDERDALE Alan Mendelsohn, M.D. Nathan Klein, O.D. 954.894.1500 Welcome to Eye Surgeons and Consultants! WE USE THE MOST ADVANCED TECHNOLOGY AND CUSTOMIZE OUR SERVICE TO YOUR EYES! SERVICES For your convenience, we also have a full service optical dispensary Laser Cataract Surgery with the highest quality and huge selection of the latest styles of Laser Vision Correction eyeglasses and sunglasses, including: Glaucoma Laser Surgery Comprehensive Eye Exams Oliver Peoples • Michael Kors • Barton Perreira • Tom Ford • Burberry Macular Degeneration Marc Jacobs • Lily Pulitzer • Mont Blanc • Nike Flexon • Silhouette Diabetic Eye Exams Glaucoma Exams We provide personalized, professional care using Red Eye Evaluations a state-of-the-art computerized in-house laboratory. Dry Eye EXTENDED HOURS: MON: 7:30AM – 8:00PM Contact Lens Exams TUE – FRI: 7:30AM – 4:30PM • SUN: 7:30AM – 11:30AM Scleral Contact Lenses 4651 Sheridan Street, Suite 100, Hollywood, FL 33021 • 954.894.1500 PLEASE SEE OUR WEBSITE: www.myeyesurgeons.com for sight-saving suggestions! YOUNG ISRAEL OF HOLLYWOOD-FT. LAUDERDALE JULY-AUGUST 2020 PAGE 3 RABBI’S MESSAGE CONSOLATION THROUGH RECONSIDERATION The Shabbat after Tisha B’Av is referred to by the special Loving G-d must express itself in actions. Rabbi Avi Weiss Haftorah that we read, Shabbat Nachamu. The term “nechama” tells a story: Whenever his parents flew to New York, it was his is generally translated as “comfort” or “consolation.” In the responsibility to meet them at the airport. -

Yosef's "Sweet Revenge" Be Able to Control His Physical Lusts

בס''ד בס''ד SHABBAT SCHEDULE We would like to wish a Hearty Mazal WEEKLY SCHEDULE Mincha 5:20pm Tov to our Dear friends Yosef & Hannah SUNDAY Shir Hashir im: 5:40pm Ayash on the Bat Mitzvah of their Dear Shaharit: 7:30am Candle Lighting: 5:16pm Daughter Judit. They should always have Minha 5:25pm Daf Yomi 8:00am many Semahot & see her grow in the Followed by Arvit & Shaharit: 8:30am Teenager Program Path of Torah & Yirat Shamayim Amen! Youth Minyan: 9:00am Zeman Keriat Shema 9:04am MONDAY TO FRIDAY 2nd Zeman Keriat Shema 9:41am We would like to wish a Hearty Mazal Shiur 6:10am Shiur: 4:20pm Tov to our Dear friends Isaie & Nicole Shaharit 6:30am Minha: 5:00pm Bouhadana on the Birth of a Grandson to Followed by Seudat Shelishit & Hodu Approx: 6:45am Dr. & Mrs. Michael Bouhadana. They Minha 5:25pm Arvit Shabbat Ends: 6:16pm should always have many Semahot & see Followed By Arbit him grow in the Path of Torah & Yirat & Shiurim in English & Rabbenu Tam 6:47pm Avot Ubanim 7:30pm Shamayim Amen! Spanish. We would like to remind our Kahal Kadosh to please Donate wholeheartedly towards our Beautiful Kehila. Anyone interested in donating for any occasion, Avot Ubanim $120, Kiddush $350, Seudat Shelishit $275, Weekly Bulletin $150, Weekly Daf Yomi $180, Daf Yomi Masechet $2500, Yearly Daf Yomi $5000, Weekly Breakfast $150, Weekly Learning $500, Monthly Rent $3500, & Monthly Learning $2000, Please contact the Rabbi. Thanking you in advance for your generous support. Tizke Lemitzvot! בס''ד Refuah Shelema List Men Women • Yosef Zvi Ben Sara Yosefia,