The United States and the 1936 Berlin Olympic Games

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SURVEY of CURRENT BUSINESS September 1935

SEPTEMBER 1935 OF CURRENT BUSINE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE BUREAU OF FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC COMMERCE WASHINGTON VOLUME 15 NUMBER 9 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis UNITED STATES BUREAU OF MINES MINERALS YEARBOOK 1935 The First Complete Official Record Issued in 1935 A LIBRARY OF CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE MINERAL INDUSTRY (In One Volume) Survey of gold and silver mining and markets Detailed State mining reviews Current trends in coal and oil Analysis of the extent of business recovery for vari- ous mineral groups 75 Chapters ' 59 Contributors ' 129 Illustrations - about 1200 Pages THE STANDARD AUTHENTIC REFERENCE BOOK ON THE MINING INDUSTRY CO NT ENTS Part I—Survey of the mineral industries: Secondary metals Part m—Konmetals- Lime Review of the mineral industry Iron ore, pig iron, ferro'alloys, and steel Coal Clay Coke and byproducts Abrasive materials Statistical summary of mineral production Bauxite e,nd aluminum World production of minerals and economic Recent developments in coal preparation and Sulphur and pyrites Mercury utilization Salt, bromine, calcium chloride, and iodine aspects of international mineral policies Mangane.se and manganiferous ores Fuel briquets Phosphate rock Part 11—Metals: Molybdenum Peat Fuller's earth Gold and silver Crude petroleum and petroleum products Talc and ground soapstone Copper Tungsten Uses of petroleum fuels Fluorspar and cryolite Lead Tin Influences of petroleum technology upon com- Feldspar posite interest in oil Zinc ChroHHtt: Asbestos -

Pm Khalid-08.04.2019 Pressematerial

FKP Scorpio Konzertproduktionen GmbH Große Elbstr. 277 a ∙ 22767 Hamburg Tel. (040) 853 88 888 ∙ www.fkpscorpio.com PRESSEMITTEILUNG 08.04.2019 FKP Scorpio und Melt! Booking in Kooperation mit AEG präsentieren: Khalid im Herbst mit seinem zweiten Album „Free Spirit“ auf Tour in Deutschland! Live in Hamburg, Frankfurt, Oberhausen und München! Im Rahmen seiner Free-Spirit-World-Tour kündigte der mehrfach mit Platin ausgezeichnete R&B Sänger Khalid vier Shows in Deutschland an. Die Ankündigung der Free- Spirit-World-Tour folgte auf die Veröffentlichung seines mit Spannung erwarteten neuen Albums „Free Spirit“. Khalids Debütalbum „American Teen“ (2017) kletterte bis auf Platz vier der Billboard Charts, erreichte Doppelplatin und wurde für fünf (!) Grammys nominiert – nun veröffentlicht US-Shootingstar Khalid sein zweites Album „Free Spirit“. Mit seinem neuen Album kommt Khalid im September und Oktober für insgesamt vier Headline- Shows nach Deutschland. Begleitet wird Khalid von Mabel und Raye, die als Support Acts für die Shows in Hamburg, Frankfurt, Oberhausen und München bestätigt sind. Erst im Oktober vergangenen Jahres hatte Khalid mit „Suncity“ eine Sieben-Track-EP vorgelegt, die u.a. die beiden mit Gold ausgezeichneten US-Hitsingles „Better“ und „Saturday Nights“ hervorbrachte. Neben fünf Grammy-Nominierungen und einem US- Doppelplatin-Top-5-Album stehen bereits ein halbes Dutzend internationaler Hits und Kollabos (u.a. „Rollin“ mit Calvin Harris, „1-800-273-8255” mit Logic und Alessia Cara, „Lovely” mit Billie Eilish, „Youth” mit Shawn Mendes) sowie ausverkaufte Konzerte auf der ganzen Welt zu Buche. Präsentiert werden die Konzerte von MTV und Digster Pop. KHALID – FREE SPIRIT TOUR Special Guests: MABEL & RAYE 09.09.2019 Hamburg - Barclaycard Arena 28.09.2019 Frankfurt - Jahrhunderthalle 02.10.2019 Oberhausen - König-Pilsner-Arena 09.10.2019 München - Zenith FKP Scorpio Konzertproduktionen GmbH Große Elbstr. -

August 1935) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 8-1-1935 Volume 53, Number 08 (August 1935) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 53, Number 08 (August 1935)." , (1935). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/836 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ETUDE AUGUST 1935 PAGE 441 Instrumental rr Ensemble Music easy QUARTETS !£=;= THE BRASS CHOIR A COLLECTION FOR BRASS INSTRUMENTS , saptc PUBLISHED FOR ar”!S.""c-.ss;v' mmizm HIM The well ^uiPJ^^at^Jrui^“P-a0[a^ L DAY IN VE JhEODORE pRESSER ^O. DIRECT-MAIL SERVICE ON EVERYTHING IN MUSIC PUBLICATIONS * A Editor JAMES FRANCIS COOKE THE ETUDE Associate Editor EDWARD ELLSWORTH HIPSHER Published Monthly By Music Magazine THEODORE PRESSER CO. 1712 Chestnut Street A monthly journal for teachers, students and all lovers OF music PHILADELPHIA, PENNA. VOL. LIIINo. 8 • AUGUST, 1935 The World of Music Interesting and Important Items Gleaned in a Constant Watch on Happenings and Activities Pertaining to Things Musical Everyw er THE “STABAT NINA HAGERUP GRIEG, widow of MATER” of Dr. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

FLOOD of AUGUST 1935 Dtf MUSKINGUM RIVER Z < 5

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Harold L. Ickes, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. C. Mendenhall, Director Water-Supply Paper 869 FLOOD OF AUGUST 1935 dtf MUSKINGUM RIVER o O z < 5 BY i ;> ^, C. V. YOUNGQUIST AND W. B. WITH SECTIONS ON THE ASSOCIATES METEOROLOGY AND HYDROLOOT ^ ;j . » BY * V WALDO E. SMITH AND A. K. SHOWALTEK 2. Prepared in cooperation with the * ^* FEDERAL EMERGENCY ADMINISTRAflCg^ OF PUBLIC WORKS ' -o j; UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON : 1941 jFor sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. G. - * * « Price 40 cents (paper) CONTENTS Pag« Abstract---.--_-_-__-__-___--______.-__-_---_---_-__-_--_-__-.-_._ I Introduction.______________________________________________________ 1 Administration and personnel---_______--_-_____-__--____________-__ 3 Acknowledgments ________-________-----_--__--__-_________________ 3 Geography _ ____________________________________________________ 6 Topography, drainage, and transportation________________________ 6 Rainfall...--_---.-__-------.-_--------__..---_-----------_---- 7 Population, industry, and mineral resources_---_-__--_________--__ 8 Flood control-___-_-___-__-_-__-____-_--_-_-__--_--__.____--_- S General features of the flood-_______________________________________ 9 Damage.-__-_______--____-__--__--__-_-____--_______-____--__ IT Meteorologic and hydrologic conditions, by Waldo E. Smith____________ 19 General features of the storm.___-____-__________---_____--__--_ 19 Records of precipitation._______________________________________ 21 Antecedent -

Nazi Privatization in 1930S Germany1 by GERMÀ BEL

Economic History Review (2009) Against the mainstream: Nazi privatization in 1930s Germany1 By GERMÀ BEL Nationalization was particularly important in the early 1930s in Germany.The state took over a large industrial concern, large commercial banks, and other minor firms. In the mid-1930s, the Nazi regime transferred public ownership to the private sector. In doing so, they went against the mainstream trends in western capitalistic countries, none of which systematically reprivatized firms during the 1930s. Privatization was used as a political tool to enhance support for the government and for the Nazi Party. In addition, growing financial restrictions because of the cost of the rearmament programme provided additional motivations for privatization. rivatization of large parts of the public sector was one of the defining policies Pof the last quarter of the twentieth century. Most scholars have understood privatization as the transfer of government-owned firms and assets to the private sector,2 as well as the delegation to the private sector of the delivery of services previously delivered by the public sector.3 Other scholars have adopted a much broader meaning of privatization, including (besides transfer of public assets and delegation of public services) deregulation, as well as the private funding of services previously delivered without charging the users.4 In any case, modern privatization has been usually accompanied by the removal of state direction and a reliance on the free market. Thus, privatization and market liberalization have usually gone together. Privatizations in Chile and the UK, which began to be implemented in the 1970s and 1980s, are usually considered the first privatization policies in modern history.5 A few researchers have found earlier instances. -

Presentation Slides

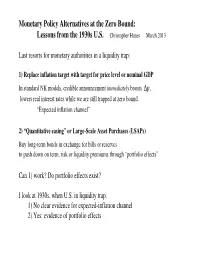

Monetary Policy Alternatives at the Zero Bound: Lessons from the 1930s U.S. Christopher Hanes March 2013 Last resorts for monetary authorities in a liquidity trap: 1) Replace inflation target with target for price level or nominal GDP In standard NK models, credible announcement immediately boosts ∆p, lowers real interest rates while we are still trapped at zero bound. “Expected inflation channel” 2) “Quantitative easing” or Large-Scale Asset Purchases (LSAPs) Buy long-term bonds in exchange for bills or reserves to push down on term, risk or liquidity premiums through “portfolio effects” Can 1) work? Do portfolio effects exist? I look at 1930s, when U.S. in liquidity trap. 1) No clear evidence for expected-inflation channel 2) Yes: evidence of portfolio effects Expected-inflation channel: theory Lessons from the 1930s U.S. β New-Keynesian Phillips curve: ∆p ' E ∆p % (y&y n) t t t%1 γ t T β a distant horizon T ∆p ' E [∆p % (y&y n) ] t t t%T λ j t%τ τ'0 n To hit price-level or $AD target, authorities must boost future (y&y )t%τ For any given path of y in near future, while we are still in liquidity trap, that raises current ∆pt , reduces rt , raises yt , lifts us out of trap Why it might fail: - expectations not so forward-looking, rational - promise not credible Svensson’s “Foolproof Way” out of liquidity trap: peg to depreciated exchange rate “a conspicuous commitment to a higher price level in the future” Expected-inflation channel: 1930s experience Lessons from the 1930s U.S. -

Fighting for Acceptance

FIGHTING FOR ACCEPTANCE: SIGFRID EDSTR0M AND AVERY BRUNDAGE: THEIR EFFORTS TO SHAPE AND CONTROL WOMEN'S PARTICIPATION IN THE OLYMPIC GAMES Carly Adams* In the twenty-first century, women train for and compete in grueling and physically taxing sports that were once considered appropriate for men only. Such participation was considered inappropriate by the Modern Olympic Games founder Pierre de Cou- bertin and his aristocratic colleagues who were fiercely opposed to the sight of straining, sweaty, muscular women participating in arduous physical activities. The Olympic Games, as Coubertin's personal venture, supported by traditional upper-class male sport leaders, were established to celebrate and embrace the physical accomplishments of men, not women. Reflecting Victorian notions of his time, sport to Coubertin was an arena for the development of human sporting bodies, and the traditional masculine virtues of strength and moral character. Like any other organization, these Games had leadership that mapped out specific goals and rules, with their intentions and values manifested through the creation of governing policies. There has long been a struggle for control over, and acceptance of, women's sports within the modern Olympic movement. Women have been active in sport since the 19th century; they even competed unofficially at the Olympic Games in golf and tennis as early as 1900. However, from the onset, women's participation has been an uphill battle characterized by restrictions, modera- tion, and exclusion. Since the establishment of the International Olympic Committee (IOC) in 1894, women sport leaders have been challenging the anachronistic ideas of the IOC, fighting for their right to participate in this traditionally male preserve. -

John F. Kennedy and Berlin Nicholas Labinski Marquette University

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Master's Theses (2009 -) Dissertations, Theses, and Professional Projects Evolution of a President: John F. Kennedy and Berlin Nicholas Labinski Marquette University Recommended Citation Labinski, Nicholas, "Evolution of a President: John F. Kennedy and Berlin" (2011). Master's Theses (2009 -). Paper 104. http://epublications.marquette.edu/theses_open/104 EVOLUTION OF A PRESIDENT: JOHN F. KENNEDYAND BERLIN by Nicholas Labinski A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Milwaukee, Wisconsin August 2011 ABSTRACT EVOLUTION OF A PRESIDENT: JOHN F. KENNEDYAND BERLIN Nicholas Labinski Marquette University, 2011 This paper examines John F. Kennedy’s rhetoric concerning the Berlin Crisis (1961-1963). Three major speeches are analyzed: Kennedy’s Radio and Television Report to the American People on the Berlin Crisis , the Address at Rudolph Wilde Platz and the Address at the Free University. The study interrogates the rhetorical strategies implemented by Kennedy in confronting Khrushchev over the explosive situation in Berlin. The paper attempts to answer the following research questions: What is the historical context that helped frame the rhetorical situation Kennedy faced? What rhetorical strategies and tactics did Kennedy employ in these speeches? How might Kennedy's speeches extend our understanding of presidential public address? What is the impact of Kennedy's speeches on U.S. German relations and the development of U.S. and German Policy? What implications might these speeches have for the study and execution of presidential power and international diplomacy? Using a historical-rhetorical methodology that incorporates the historical circumstances surrounding the crisis into the analysis, this examination of Kennedy’s rhetoric reveals his evolution concerning Berlin and his Cold War strategy. -

Hitler's American Model

Hitler’s American Model The United States and the Making of Nazi Race Law James Q. Whitman Princeton University Press Princeton and Oxford 1 Introduction This jurisprudence would suit us perfectly, with a single exception. Over there they have in mind, practically speaking, only coloreds and half-coloreds, which includes mestizos and mulattoes; but the Jews, who are also of interest to us, are not reckoned among the coloreds. —Roland Freisler, June 5, 1934 On June 5, 1934, about a year and a half after Adolf Hitler became Chancellor of the Reich, the leading lawyers of Nazi Germany gathered at a meeting to plan what would become the Nuremberg Laws, the notorious anti-Jewish legislation of the Nazi race regime. The meeting was chaired by Franz Gürtner, the Reich Minister of Justice, and attended by officials who in the coming years would play central roles in the persecution of Germany’s Jews. Among those present was Bernhard Lösener, one of the principal draftsmen of the Nuremberg Laws; and the terrifying Roland Freisler, later President of the Nazi People’s Court and a man whose name has endured as a byword for twentieth-century judicial savagery. The meeting was an important one, and a stenographer was present to record a verbatim transcript, to be preserved by the ever-diligent Nazi bureaucracy as a record of a crucial moment in the creation of the new race regime. That transcript reveals the startling fact that is my point of departure in this study: the meeting involved detailed and lengthy discussions of the law of the United States. -

The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany Nathan W

Student Publications Student Scholarship Spring 2016 The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany Nathan W. Cody Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship Part of the European History Commons, Political History Commons, Social History Commons, and the Sports Studies Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Cody, Nathan W., "The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany" (2016). Student Publications. 434. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/434 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/student_scholarship/ 434 This open access student research paper is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Berlin Olympics: Sports, Anti-Semitism, and Propaganda in Nazi Germany Abstract The aN zis utilized the Berlin Olympics of 1936 as anti-Semitic propaganda within their racial ideology. When the Nazis took power in 1933 they immediately sought to coordinate all aspects of German life, including sports. The process of coordination was designed to Aryanize sport by excluding non-Aryans and promoting sport as a means to prepare for military training. The 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin became the ideal platform for Hitler and the Nazis to display the physical superiority of the Aryan race. However, the exclusion of non-Aryans prompted a boycott debate that threatened Berlin’s position as host. -

Avery Brundage

Historical Archives Olympic Studies Centre Avery Brundage Fonds list Overview of the content of the archives concerning his biography, mandates and activities from 1908 to 1989 14 April 2011 © 2011 / International Olympic Committee (IOC) / BACHRACH, Fabian Fonds list Reference: CH CIO-AH A-P05 Dates: 1908-1989 Level of description: Fonds Extent and medium: 1.51 l.m. Text documents and microfilms. Name of creator International Olympic Committee (IOC). Administrative / Biographical history Avery Brundage was born in 1887 in Detroit, Michigan (USA). He came from a modest family, of which the father, Charles Brundage, was a stonemason. His secondary education took place at the Crane Manual Training School in Chicago. He then went on to the University of Illinois, where he obtained a diploma in civil engineering in 1909. As well as being an outstanding student, Brundage was also an accomplished athlete. A follower of athletics, he practised several sports throughout his studies and alongside his various professional activities. In 1912, his passion for athletics led him to the Olympic Games (OG) in Stockholm, where he represented the United States in the pentathlon and decathlon events, finishing in sixth and 16th place respectively. Furthermore, two years later, he obtained the title of American national champion in “all-around”, a discipline similar to decathlon, but where the events take place on a single day. He went on to win this competition twice again, in 1916 and 1918. The fame he gained through this throughout the American sports world was not unconnected to his later involvement in the Olympic Movement. Brundage added professional success to his sporting success.