Ukrainian Far Right

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Dilemmas of Civic Revival: Ukrainian Women Since Independence

Journal of Ukrainian Studies 26, nos. 1–2 (Summer–Winter 2001) The Dilemmas of Civic Revival: Ukrainian Women since Independence Alexandra Hrycak* Motherhood, full-time work, and active citizenship—these were the three social roles the Soviet state officially expected women to perform. In practice, however, that state encouraged women in Ukraine to put motherhood above career advancement and permitted them to engage only in officially condoned civic causes. The late 1980s initiated a broad-based civic revival that provided many women opportunities to develop new political skills that enhanced their ability to contribute to their communities. However, the first ten years of Ukraine’s post-Soviet existence profoundly challenged their capacity to ensure the carrying out of the political and social reforms women activists sought during glasnost. This article examines some of the ways in which Ukrainian women have altered their orientation to motherhood, work, and citizenship in response to the tumultuous changes of the last decade. I begin by exploring some of the broader problems that have led to declining women’s health, socio-economic status, and political influence. I then evaluate in detail the causes of recent shifts in household composition and family structure. Next I analyze the factors that limit women’s ability to improve their position in the labour force. I conclude by examining women’s influence over politics and public life during the Soviet era and the first years of Ukraine’s independence. * I would like to thank the International Research and Exchanges Board and Reed College for the financial support that made this research possible. -

Svoboda Party – the New Phenomenon on the Ukrainian Right-Wing Scene

OswcOMMentary issue 56 | 04.07.2011 | ceNTRe fOR eAsTeRN sTudies Svoboda party – the new phenomenon on the Ukrainian right-wing scene NTARy Me Tadeusz A. Olszański ces cOM Even though the national-level political scene in Ukraine is dominated by the Party of Regions, the west of the country has seen a progressing incre- ase in the activity of the Svoboda (Freedom) party, a group that combines tudies participation in the democratically elected local government of Eastern s Galicia with street actions, characteristic of anti-system groups. This party has brought a new quality to the Ukrainian nationalist movement, as it astern refers to the rhetoric of European anti-liberal and neo-nationalist move- e ments, and its emergence is a clear response to public demand for a group of this sort. The increase in its popularity plays into the hands of the Party of Regions, which is seeking to weaken the more moderate opposition entre for parties (mainly the Yulia Tymoshenko Bloc). However, Svoboda retains its c independence from the ruling camp. This party, in all likelihood, will beco- me a permanent and important player in Ukrainian political life, although its influence may be restricted to Eastern Galicia. NTARy Me Svoboda is determined to fight the tendencies in Ukrainian politics and the social sphere which it considers pro-Russian. Its attitude towards Russia and Russians, furthermore, is unambiguously hostile. In the case of Poland, ces cOM it reduces mutual relations almost exclusively to the historical aspects, strongly criticising the commemoration of the victims of the Ukrainian Insurgent Army’s (UPA) crimes. -

FROM DESPAIR to HOPE LGBT Situation in Ukraine in 2014

FROM DESPAIR TO HOPE LGBT situation in Ukraine in 2014 LGBT Human Rights Nash Mir Center Council of LGBT Organizations of Ukraine Kyiv 2015 From Despair to Hope. LGBT situation in Ukraine in 2014 This publication provides information that reflects the social, legal and political situation of the LGBT (lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender) community in Ukraine in 2014. Here are to be found data and analyses on issues related to the rights and interests of LGBT persons in legislation, public and political life, public opinion, and examples of discrimination on the ground of sexual orientation etc. Authors: Andrii Kravchuk, Oleksandr Zinchenkov Project Manager of Nash Mir Center: Andriy Maymulakhin The authors would like to thank NGOs Association LGBT LIGA, Gay Forum of Ukraine, Lyudy Bukoviny, LGBT Union You Are Not Alone and all active participants in the LGBT Leaders e-mailing list and Facebook groups who collect and exchange relevant information on various aspects of the situation of LGBT people in Ukraine. Very special thanks to J. Stephen Hunt (Chicago, USA) for his proofreading of the English text and long-lasting generous support. The report is supported by Council of LGBT Organizations of Ukraine. The report “From Despair to Hope. LGBT situation in Ukraine in 2014” was prepared by Nash Mir Center as part of the project “Promoting LGBT rights in Ukraine through monitoring, legal protection & raising public awareness”. This project is realised by Nash Mir in cooperation with the Norwegian Helsinki Committee, within the framework of the program "Promotion of human rights and rule of law for lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender persons in Ukraine" which is funded by the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. -

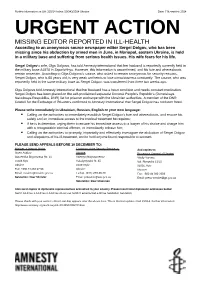

Urgent Action

Further information on UA: 215/14 Index: 50/043/2014 Ukraine Date: 7 November 2014 URGENT ACTION MISSING EDITOR REPORTED IN ILL-HEALTH According to an anonymous source newspaper editor Sergei Dolgov, who has been missing since his abduction by armed men in June, in Mariupol, eastern Ukraine, is held in a military base and suffering from serious health issues. His wife fears for his life. Sergei Dolgov’s wife, Olga Dolgova, has told Amnesty international that her husband is reportedly currently held in the military base A1978 in Zaporizhhya. However, this information is unconfirmed, and his fate and whereabouts remain uncertain. According to Olga Dolgova’s source, who asked to remain anonymous for security reasons, Sergei Dolgov, who is 60 years old, is very weak and tends to lose consciousness constantly. The source, who was reportedly held in the same military base as Sergei Dolgov, was transferred from there two weeks ago. Olga Dolgova told Amnesty International that her husband has a heart condition and needs constant medication. Sergei Dolgov has been placed on the self-proclaimed separatist Donetsk People’s Republic‘s (Donetskaya Narodnaya Respublika, DNR) list for prisoner exchange with the Ukrainian authorities. A member of the DNR Council for the Exchange of Prisoners confirmed to Amnesty International that Sergei Dolgov has not been freed. Please write immediately in Ukrainian, Russian, English or your own language: . Calling on the authorities to immediately establish Sergei Dolgov’s fate and whereabouts, and ensure his safety and an immediate access to the medical treatment he requires; . If he is in detention, urging them to ensure his immediate access to a lawyer of his choice and charge him with a recognizable criminal offence, or immediately release him; . -

MANUFACTURING MORAL PANIC: Weaponizing Children to Undermine Gender Justice and Human Rights

MANUFACTURING MORAL PANIC: Weaponizing Children to Undermine Gender Justice and Human Rights Research Team: Juliana Martínez, PhD; Ángela Duarte, MA; María Juliana Rojas, EdM and MA. Sentiido (Colombia) March 2021 The Elevate Children Funders Group is the leading global network of funders focused exclusively on the wellbeing and rights of children and youth. We focus on the most marginalized and vulnerable to abuse, neglect, exploitation, and violence. Global Philanthropy Project (GPP) is a collaboration of funders and philanthropic advisors working to expand global philanthropic support to advance the human rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and intersex (LGBTI) people in the Global1 South and East. TABLE OF CONTENTS Glossary ...................................................................................... 4 Acronyms .................................................................................................. 4 Definitions ................................................................................................. 5 Letter from the Directors: ......................................................... 8 Executive Summary ................................................................... 10 Report Outline ..........................................................................................13 MOBILIZING A GENDER-RESTRICTIVE WORLDVIEW .... 14 The Making of the Contemporary Gender-Restrictive Movement ................................................... 18 Instrumentalizing Cultural Anxieties ......................................... -

Urgent Action

UA: 297/14 Index: EUR 50/045/2014 Ukraine Date: 24 November 2014 URGENT ACTION ESTABLISH WHEREABOUTS OF DISAPPEARED MAN Aleksandr Minchenok, a 31-year-old civilian man from Lisichansk, disappeared on 21 July after being “arrested” by pro-Kyiv forces while travelling with his grandmother in eastern Ukraine. His parents, who have not heard from him since July, fear for his life. On the morning of 21 July Aleksandr Minchenok was traveling in his car with his grandmother Maria Naumova from Lisichansk, a town in Luhansk Region, to Kharkiv. He called his parents to tell them that they had passed the checkpoints controlled by pro-Russian separatist near Severodonetsk. After about 30 minutes, an unknown person who did not identify himself called Aleksandr Minchenok’s parents and told them that their son had been arrested and was being taken to the Prosecutor’s office. After this phone call, neither Aleksandr Minchenok nor the unknown caller could be reached again. Ekaterina Naumova and Yuriy Naumov, Aleksandr Minchenok’s parents, rushed to their son’s last known location and found people who told them that their son had been apprehended by the territorial defence battalion Aidar, one of over thirty so-called volunteer battalions to have emerged as part of the pro-Kyiv forces in the wake of the conflict. Members of the pro-Kyiv forces present at the site told the parents that Aleksandr Minchenok had already been released near Starobelsk, a town a short distance from Luhansk. Aleksandr Minchenok’s grandmother said that they had been stopped by men in military uniforms, but she could not remember what insignia they had. -

Ukraine at the Crossroad in Post-Communist Europe: Policymaking and the Role of Foreign Actors Ryan Barrett [email protected]

University of Missouri, St. Louis IRL @ UMSL Dissertations UMSL Graduate Works 1-20-2018 Ukraine at the Crossroad in Post-Communist Europe: Policymaking and the Role of Foreign Actors Ryan Barrett [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation Part of the Comparative Politics Commons, and the International Relations Commons Recommended Citation Barrett, Ryan, "Ukraine at the Crossroad in Post-Communist Europe: Policymaking and the Role of Foreign Actors" (2018). Dissertations. 725. https://irl.umsl.edu/dissertation/725 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the UMSL Graduate Works at IRL @ UMSL. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of IRL @ UMSL. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Ukraine at the Crossroad in Post-Communist Europe: Policymaking and the Role of Foreign Actors Ryan Barrett M.A. Political Science, The University of Missouri - Saint Louis, 2015 M.A. International Relations, Webster University, 2010 B.A. International Studies, 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School at the The University of Missouri - Saint Louis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor Philosophy in Political Science May 2018 Advisory Committee: Joyce Mushaben, Ph.D. Jeanne Wilson, PhD. Kenny Thomas, Ph.D. David Kimball, Ph.D. Contents Introduction 1 Chapter I. Policy Formulation 30 Chapter II. Reform Initiatives 84 Chapter III. Economic Policy 122 Chapter IV. Energy Policy 169 Chapter V. Security and Defense Policy 199 Conclusion 237 Appendix 246 Bibliography 248 To the Pat Tillman Foundation for graciously sponsoring this important research Introduction: Ukraine at a Crossroads Ukraine, like many European countries, has experienced a complex history and occupies a unique geographic position that places it in a peculiar situation be- tween its liberal future and communist past; it also finds itself tugged in two opposing directions by the gravitational forces of Russia and the West. -

DP Khrushchev

УДК 552.14:004.942 REGIONAL STRUCTURAL-LITHOLOGICAL1MODELING OF SEDIMENTARY COVER D.P. Khrushchev Institute of Geological Sciences of NAS of Ukraine, Kiev, Ukraine, E-mail: [email protected] Doctor of geological-mineralogical sciences, professor, senior research worker. The idea of the project is the construction of computer (digital) structural-lithological models (DSLM) of sedimentary cover for state territories on regional principle proceeding from the defi- nition of geological region as a basic geostructural unit of Earth crust. Digital structural-lithological model – it is three-demensional computer representation of the geological objects, comprising it’s structural and qualitative characteristics. Methodological principles, methods, available de- velopments and modeling patterns are reflected to prove the feasibility of the project realization. Practical goal of modeling is the creation of integral geoinformatic foundation for multilateral cog- nitive image of an object and for information provision of all directories and kinds of human geo- logical activity (R&D) on multilateral use and protection (including geological hazards) of geological environment. The result achieved is obtaining of single united system of regional DSLM on state territorial level. The project proposed represents a part of conceptual compound project, the object of which has to comprise both sedimentary cover and magmatic, metamorphic for- mations. The achieved result of such a project is the developing of the integral digital structural- lithological-petrological model of Earth crust as a whole. Key words: sedimentary formations, sedimentary cover, computer modeling, geoinformatic sy- stem, geological environment use, geological environment protection. РЕГІОНАЛЬНЕ СТРУКТУРНО-ЛІТОЛОГІЧНЕ МОДЕЛЮВАННЯ ОСАДОВОЇ ОБОЛОНКИ Д.П. Хрущов Інститут геологічних наук НАН України, Київ, Україна, E-mail: [email protected] Доктор геолого-мінералогічних наук, професор, старший науковий співробітник. -

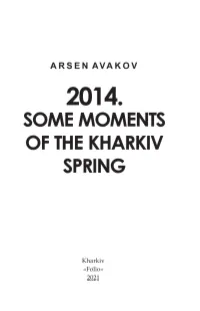

Аваков Kharkov 2014 Engl Site.Pdf

ARSEN AVAKOV CONTENTS Foreword by the Author . 6 How did We Win That Spring? . 8 Ukraine . February—April 2014 . Headlines Only . 20. Kharkiv February 22—April 7, 2014 . 136 Information Warfare and the Russian Trail . 151 Rally on March 1, 2014 . The Capture of the KhOSA Building . 160 On the Eve . 170 Kharkiv April 7, 2014 . Assault of the KhOSA Building . 180 Kharkiv . April 8, 2014 . Slobozhanshchina— is Ukraine! . 208 Why We Managed to Do It in Kharkiv . 215 The Photo Chronicles . 224 Annexes . 225 4 2014: Some Moments of the Kharkiv Spring Annex 1 . 228 Annex 2 . 256 Annex 3 . 260 Annex 4 . 263 Annex 5 . 270 Annex 6 . 276 Author’s Afterword . 281 5 ARSEN AVAKOV FOREWORD BY THE AUTHOR This book is about Kharkiv and its people . And also my story about one night, several hard days, and months of troubled 2014 . That first year of the hybrid war against Ukraine and the very night that became a turning point for Kharkiv and Ukraine’s fate . After several years, I tried to analyze the events of that period in Kharkiv’s life against the background of the country’s general situation, when Putin’s regime’s military aggression was beginning, when we still did not understand real might, cynicism, and preparedness of the enemy . As the Minister of Internal Affairs, I knew the situation in the country, in every city—and I will tell you about it . But what was happening in Kharkiv, I learned both from the reports of subordinates and friends and family calls . That’s why I invited Kharkiv citizens to co-author this book—the very men and women who saw those developments with their own eyes and in those difficult days lived through both the fate of their city and their personal destiny . -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

Azov Phenomenon How Ukrai

INFORMATION GROUP ON CRIMES AGAINST THE PERSON (IGCP) INFORMATION GROUP ON CRIMES AGAINST THE PERSON (IGCP) Azov Phenomenon How Ukrainian Neo-Nazis Became Infl uential Political Force “IGCP Reports” (published since 2016) Head of the Project A.R. Dyukov. Issue 3. Editor M.A. Vilkov. Maltsev V. Azov Phenomenon How Ukrainian Neo-Nazis became Influential Political Force / Information Group on Crimes against the Person (IGCP). M.: “Istoricheskaya pamyat” Foundation, 2017. — 98 pages. There were the days when participants of right-wing and neo-Nazi groups in the Ukraine were marginal ones, being expelled to the edge of political and social life. Everything changed in 2014, during the so-called “Revolution of Dignity”. Ukrainian neo-Nazis gained money and weapon, they were given official status as Army, Police and Special Forces units, they got representatives in the Parliament. The history of “Azov” — notorious neo- Nazi detachment of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of the Ukraine — became an image of such transformation. “Azov” offsprings hold leading offices in Ukrainian Police, raise the youth in neo-Nazi ideology encirclement, effectively expand their representation on the Ukrainian political field and getting ready for the struggle for power. This report is devoted to the process of Ukrainian nationalists becoming influential political power. IGCP, 2017. Contents Preface ............................................................................7 Chapter 1. Street Militants...............................................11 Social-National Party of Ukraine .................................... 13 The Social-National Assembly ........................................ 25 Chapter 2. Neo-Nazis Get Armed ..................................... 41 Chapter 3: Forced March to Power ..................................69 Preface “Any man who has once acclaimed violence as his METHOD must inexorably choose false- hood as his PRINCIPLE.” A.I. -

URGENT ACTION NEWSPAPER EDITOR ABDUCTED in EAST UKRAINE Sergei Dolgov, the Editor of a Ukrainian Newspaper, Has Been Missing Since His Abduction by Armed Men in June

UA: 215/14 Index: EUR 50/039/2014 Ukraine Date: 5 September 2014 URGENT ACTION NEWSPAPER EDITOR ABDUCTED IN EAST UKRAINE Sergei Dolgov, the editor of a Ukrainian newspaper, has been missing since his abduction by armed men in June. Media reports suggested that he had been killed, but eyewitnesses and relatives believe he is being held in the Ukrainian city Zaporizhhya. The deputy editor of Khochu v SSSR (“I want to be in the USSR”) told Amnesty International that at around 12pm on 18 June six armed, masked men in civilian clothing stormed the offices of the newspaper in Mariupol, a city in the south east of Ukraine, and brutally dragged Sergei Dolgov into a car parked in front of the office. The men took all the technical equipment from the offices with them. The newspaper employees contacted the police, and Sergei Dologov’s wife has since filed several complaints with the police and other authorities. The police opened an investigation, but an officer working on the case reportedly said that there were different Ukrainian forces active in Mariupol that the police would not necessarily be aware of and “it might well be that Dolgov is being officially detained rather than having been abducted”. The head of the Ukrainian government security agency, Sluzhba Bezpeky Ukrayiny (SBU), in Mariupol said in an interview published by media on 21 June that Sergei Dolgov had been arrested by the National Guard of Ukraine and is being held in Zaporishia. However the SBU denied having any information about his detention or whereabouts ever since.