Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. PRESERVING LGBTQ HISTORY The chapters in this section provide a history of archival and architectural preservation of LGBTQ history in the United States. An archeological context for LGBTQ sites looks forward, providing a new avenue for preservation and interpretation. This LGBTQ history may remain hidden just under the ground surface, even when buildings and structures have been demolished. THE PRESERVATION05 OF LGBTQ HERITAGE Gail Dubrow Introduction The LGBTQ Theme Study released by the National Park Service in October 2016 is the fruit of three decades of effort by activists and their allies to make historic preservation a more equitable and inclusive sphere of activity. The LGBTQ movement for civil rights has given rise to related activity in the cultural sphere aimed at recovering the long history of same- sex relationships, understanding the social construction of gender and sexual norms, and documenting the rise of movements for LGBTQ rights in American history. -

City of Gloucester Community Preservation Committee

CITY OF GLOUCESTER COMMUNITY PRESERVATION COMMITTEE BUDGET FORM Project Name: Masonry and Palladian Window Preservation at Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House Applicant: Historic New England SOURCES OF FUNDING Source Amount Community Preservation Act Fund $10,000 (List other sources of funding) Private donations $4,000 Historic New England Contribution $4,000 Total Project Funding $18,000 PROJECT EXPENSES* Expense Amount Please indicate which expenses will be funded by CPA Funds: Masonry Preservation $13,000 CPA and Private donations Window Preservation $2,200 Historic New England Project Subtotal $15,200 Contingency @10% $1,520 Private donations and Historic New England Project Management $1,280 Historic New England Total Project Expenses $18,000 *Expenses Note: Masonry figure is based on a quote provided by a professional masonry company. Window figure is based on previous window preservation work done at Beauport by Historic New England’s Carpentry Crew. Historic New England Beauport, The Sleeper-McCann House CPA Narrative, Page 1 Masonry Wall and Palladian Window Repair Historic New England respectfully requests a $10,000 grant from the City of Gloucester Community Preservation Act to aid with an $18,000 project to conserve a portion of a masonry wall and a Palladian window at Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House, a National Historic Landmark. Project Narrative Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House, was the summer home of one of America’s first professional interior designers, Henry Davis Sleeper (1878-1934). Sleeper began constructing Beauport in 1907 and expanded it repeatedly over the next twenty-seven years, working with Gloucester architect Halfdan M. -

August 2021.Indd

Search Press Ltd August 2021 The Complete Book of patchwork, Quilting & Appliqué by Linda Seward www.searchpress.com/trade SEARCH PRESS LIMITED The world’s finest art and craft books ADVANCE INFORMATION Drawing - A Complete Guide: Nature Giovanni Civardi Publication 31st August 2021 Price £12.99 ISBN 9781782218807 Format Paperback 218 x 152 mm Extent 400 pages Illustrations 960 Black & white illustrations Publisher Search Press Classification Drawing & sketching BIC CODE/S AFF, WFA SALES REGIONS WORLD Key Selling Points Giovanni Civardi is a best-selling author and artist who has sold over 600,000 books worldwide No-nonsense advice on the key skills for drawing nature – from understanding perspective to capturing light and shade Subjects include favourites such as country scenes, flowers, fruit, animals and more Perfect book for both beginner and experienced artists looking for an inspirational yet informative introduction to drawing natural subjects This guide is bind-up of seven books from Search Press’s successful Art of Drawing series: Drawing Techniques; Understanding Perspective; Drawing Scenery; Drawing Light & Shade; Flowers, Fruit & Vegetables; Drawing Pets; and Wild Animals. Description Learn to draw the natural world with this inspiring and accessible guide by master-artist Giovanni Civardi. Beginning with the key drawing methods and essential materials you’ll need to start your artistic journey, along with advice on drawing perspective as well as light and shade, learn to sketch country scenes, fruit, vegetables, animals and more. Throughout you’ll find hundreds of helpful and practical illustrations, along with stunning examples of Civardi’s work that exemplify his favourite techniques for capturing the natural world. -

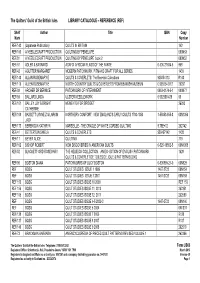

Reference (Ref)

The Quilters’ Guild of the British Isles LIBRARY CATALOGUE – REFERENCE (REF) Shelf Author Title ISBN Copy Mark Number REF/142 (Japanese Publication) QUILTS IN BRITAIN 142 REF/163 A NEEDLECRAFT PRODUCTION QUILTING BY PENELOPE 000N53 REF/81 A NEEDLECRAFT PRODUCTION QUILTING BY PENELOPE book 2 000N52 REF/61 ADLER & BARNARD ASAFO! AFRICAN FLAGS OF THE FANTE 0-500-27684-6 968 REF/42 AGUTTER MARGARET MODERN PATCHWORK PITMANS CRAFT FOR ALL SERIES 1439 REF/140 ALLAN ROSEMARY E QUILTS & COVERLETS: The Beamish Collections 905054113 R140 REF/116 ALLEN ROSEMARY E NORTH COUNTRY QUILTS & COVERLETS FROM BEAMISH MUSEUM 0 905054 03 2 26297 REF/93 ARCHER DR BERNICE PATCHWORK OF INTERNMENT 0953-0174-5-1 000N77 REF/69 BALLARD LINDA ULSTER NEEDLEWORK 0 902588 435 99 REF/101 BALLEY JOY & BRIGHT MEMENTO FOR BRIDGET 26293 CATHERINE REF/109 BASSETT LYNNE Z & LARKIN NORTHERN COMFORT: NEW ENGLAND'S EARLY QUILTS 1780-1850 1-55853-655-8 00N1056 JACK REF/173 BERENSON KATHRYN MARSEILLE - THE CRADLE OF WHITE CORDED QUILTING 9.78E+12 262742 REF/41 BETTERTON SHIELA QUILTS & COVERLETS 950497142 1438 REF/17 BEYER ALICE QUILTING 710 REF/102 BISHOP ROBERT NEW DISCOVERIES IN AMERICAN QUILTS 0-525-16552-5 00N1055 REF/52 BLACKETT-ORD ROSEMARY THE HELBECK COLLECTION . AN EXHIBITION OF ENGLISH PATCHWORK 1629 QUILTS & COVERLET DE TOILES DE JOUE & PATTERN BOOKS REF/95 BOSTON DIANA PATCHWORKS OF LUCY BOSTON 0-905899-21-0 00N629 REF BQSG QUILT STUDIES ISSUE 1 1999 1467-2723 00N154 REF BQSG QUILT STUDIES ISSUE 3 2001 1467-2723 00N158 REF 153 BQSG QUILT STUDIES ISSUE 10 2009 REF 153 -

Ghana Textile/Garment Industry- an Endangered Economic Subsector

. tMiviiu u/ cr Ct&M* a Q j SCHOOL OF ADMINISTRATION UNIVERSITY OF GHANA LEGON GHANA TEXTILE/GARMENT INDUSTRY- AN ENDANGERED ECONOMIC SUBSECTOR DR. /M O . Mensah 1 SCHOOL OF ADMINISTRATION (UNIVERSITY OF GHANA) THE MANAGEMENT MONOGRAPH SERIES GENERAL EDITOR: STEPHEN A. NKRUMAH The School of Administration Management Monograph Series is a publication devoted to research reports too short to come out in book form and yet too long for a journal article. It is a refereed publication with interest in issues relating to both basic and applied research in Management and Administration. All correspondence should be addressed to: The General Editor The Management Monograph Series School of Administration University of Ghana Legon Tel: (021) 500591 Fax: (021) 500024 E-mail: [email protected] /JW GHANA TEXTILE/GARMENT INDUSTRY - AN ENDANGERED ECONOMIC SUBSECTOR o v ITUCHff iJd&A&V A.H.O. MENSAH AFRAM PUBLICATIONS (GHANA) LIMITED IDS 029005 Published for School of Administration, University of Ghana, Legon Published by Afram Publications (Ghana) Limited, P.O. Box M 18 Accra E-mail: [email protected] © S O A All rights reserved. Except for use in any review, the reproduction or utilization of this work in whole or part in any form by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including xerography, photocopying and recording or in any information storage or retrieval system, is forbidden without the prior permission of the publishers, Afram Publications (Ghana) Limited. First Published: 1998 ISSN: 0855-3645-3 ABSTRACT For nearly three decades now, Ghana’s textile/garment industry has suffered a steep decline - a decline so steep and so rapid that if not arrested, can cause the industry to move to total extinction within the next decade or two. -

American Quilts

CATALOGUE AMERICAN QUILTS 1819 -- 1948 From the Museum Collection Compiled by Mildred Davison The Art Institute of Chicago, Department of Decorative Arts Exhibition April 20, 1959 - October 19, 1959 AMERICAN QUILTS 1819 - 1948, FROM THE MUSEUM COLLECTION The Art Institute of Chicago, April Z0 1 1959 --October 19, 1959 Although patchwork has been known and practised since ancient times, nowhere has it played such a distinctive and characteristic part as in the bed covers of early America where it added the finishing touches to eighteenth and nineteenth century bed chambers. The term "patchwork" is used indiscriminately to include the pieced and the appliqued quilts. Pieced quilts are generally geometric in pattern being a combination of small patches sewn together with narrow seams. The simplest form of pieced pattern is the eight-pointed star formed of diamond shaped patches. This was known as the Star of Le Moyne, named in honor of Jean Baptiste Le Moyne who founded New Orleans in 1718, and from it was developed numerous others including all of the lily and tulip designs. In applique quilts, pieces were cut to form the pattern and appliqued to a back - ground material with fine hemming or embroidery stitches, a method which gave a wider scope for patterns. By 1850, applique quilts reached such a degree of elaboration that many years were spent in their making and they were often intend ed for use as counterpanes. The most common fabrics for quilts were plain and figured calicoes and chintzes with white muslin..., The source of these materials in early times and pioneer communities was the scrap bag. -

A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker

LIBRARY v A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker A Dictionary of Men's Wear (This present book) Cloth $2.50, Half Morocco $3.50 A Dictionary of Engraving A handy manual for those who buy or print pictures and printing plates made by the modern processes. Small, handy volume, uncut, illustrated, decorated boards, 75c A Dictionary of Advertising In preparation A Dictionary of Men's Wear Embracing all the terms (so far as could be gathered) used in the men's wear trades expressiv of raw and =; finisht products and of various stages and items of production; selling terms; trade and popular slang and cant terms; and many other things curious, pertinent and impertinent; with an appendix con- taining sundry useful tables; the uniforms of "ancient and honorable" independent military companies of the U. S.; charts of correct dress, livery, and so forth. By William Henry Baker Author of "A Dictionary of Engraving" "A good dictionary is truly very interesting reading in spite of the man who declared that such an one changed the subject too often." —S William Beck CLEVELAND WILLIAM HENRY BAKER 1908 Copyright 1908 By William Henry Baker Cleveland O LIBRARY of CONGRESS Two Copies NOV 24 I SOB Copyright tntry _ OL^SS^tfU XXc, No. Press of The Britton Printing Co Cleveland tf- ?^ Dedication Conforming to custom this unconventional book is Dedicated to those most likely to be benefitted, i. e., to The 15000 or so Retail Clothiers The 15000 or so Custom Tailors The 1200 or so Clothing Manufacturers The 5000 or so Woolen and Cotton Mills The 22000 -

Patricia Cox Crews

1 PATRICIA COX CREWS The University of Nebraska-Lincoln Department of Textiles, Merchandising & Fashion Design Lincoln, Nebraska 68583-0802 Office: (402) 472-6342 Home: (402) 488-8371 EDUCATION Degree Programs 1971 B.S., Virginia Tech, Fashion Design and Merchandising. 1973 M.S., Florida State University, Textile Science. 1984 Ph.D., Kansas State University, Textile Science and Conservation. Other Education 1982 Organic Chemistry for Conservation, Smithsonian Institute Certificate of Training (40 hours). 1985 Historic Dyes Identification Workshop, Smithsonian Conservation Analytical Lab, Washington, D.C. 1990 Colorimetry Seminar, Hunter Associates, Kansas City, MO. 1994 Applied Polarized Light Microscopy, McCrone Research Institute, Chicago, IL. 2007 Museum Leadership Institute, Getty Foundation, Los Angeles, CA. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 1984- University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Willa Cather Professor of Textiles, 2003-present; Founding Director Emeritus, International Quilt Study Center & Museum, 1997- 2013; Professor, 1996-present; Acting Chair, Dept. of Textiles, Clothing & Design, 2000; Chair, Interdisciplinary Museum Studies Program, 1995-1997; Associate Professor, 1989-1996; Assistant Professor, 1984-89. Courses taught: Textile History, Care and Conservation of Textile Collections, Artifact Analysis, Textile Dyeing, and Advanced Textiles. 1982 Summer Internship. Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History-Division of Textiles. 1977-84 Kansas State University, Manhattan, Kansas, Instructor of Textiles. 1976-77 Bluefield State College, Bluefield, West Virginia, Instructor of Textiles and Weaving. 1975 Virginia Western Community College, Roanoke, Virginia, Instructor of Textiles and Weaving. 1973-74 Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, Instructor of Textiles. HONORS AND AWARDS 2013 Reappointed to Willa Cather Professorship in recognition of distinguished scholarship. 2009 University of Nebraska, College of Education & Human Sciences Faculty Mentoring Award. -

A Sampling of Uncommon Decoration by Montgomery Artists & Artisans Past & Present

Montgomery Historical Society P.O. Box 47 Montgomery, VT 05470 [email protected] www.montgomeryhistoricalsociety.org Creative Montgomery: A Sampling of Uncommon Decoration by Montgomery Artists & Artisans Past & Present Illumination Titus Livius - History of Rome (circa 1990s) by Carl Tcherny Lion (circa 1980) by Carl Tcherny § Early American Decoration Award Winning Theorem Reproduction by Parma Jewett (2012) Based on a circa 1740s original. Victorian Flower Painting Covered Bridge Mail Box (2006) by Parma Jewett Reverse Glass Painted Game Table (circa 1900) by Savanard Jewett Stenciled Linens (circa 1950) by Marion Towle Theorem Painting Demonstration by Parma Jewett § Sewing & Quilts “Montgomery Flower Garden” (2014) by members of the Franklin County Quilters Guild Nine Patch on Point with Sashing (circa 1890) maker unknown hand pieced and hand quilted. (acquired at Pratt Family Auction in Montgomery) Quilt Block Decorated Covered Bridge Mail Box by Montgomery Quilting Circle (2006) Hand Quilting Demonstration by Sharon Perry The MHS Exhibit A recent national survey ranks Vermont third in the nation with the number people who self - identify as artists. Some would say you can’t drive down a dirt road in Vermont without bumping into one (or more), so it’s no surprise that some pretty interesting stuff can be found in almost every nook and cranny of the State. The Montgomery Historical Society exhibit focuses on decoration, whether by artist, artisan, or Everyman. In choosing our objects we hoped to display memorable things the viewer would not see anywhere else, and one might be surprised to discover coming out of rural Vermont. It includes the centuries old Illumination technique, early American decoration, quilting and contemporary examples of each. -

Volume Iv. Washington City, D. 0., June 28,1874

VOLUME IV. WASHINGTON CITY, D. 0., JUNE 28,1874. NUMBER 17. can speak sentiments so fair and uncontaminated The Beecher Case. malice replete. I couldn't help it—I dressed, Trent LATEST BT TELEGRAPH. NEW. YORK, June 27.—J. B. Carpenter, artist, men- THE CAPITAL, down into the street and threw a stone at him. with passion, merits a call from his feilow-citizens to tioned In Tilton's letter to Beecher as the person Who PUBLISHED WEEKLY But our nights here, are lovely. If we have the a position where they may give life to opinion and SPECIALS FKOM BALTIMORB. had informed him that Beecher had said money could same moon that you have down the city, we at least firmness to action. They are not such sentiments as be obtained to send Tllton and family to Europe, if BY THJB have a different point of perspective—it is so large domesticate themselves in a narrow breast. Why THE CITY HALL AGAIN. tiling to go, lias been interviewed and says : " A few CAPITAL PUBLISHING COMPANY, and so luminous, the sky so vast and so blue, the should not the name of their gallant and generous BALTIMORE, June 27.—An article that recently ap- days after the adjournment of the council I had occa- 927 I> Street, Washington, W. €. stars so nnmerons and brilliant, and the Capitol ris- author, Who speaks what is ready to leap from every peared in this corresppndencé relative to alleged over- sion to call uponBéecher at his house, In connection BONN PIATT Editor. ing before you like some enchanted palace, with its tongue to-day, be named for. -

Transcription of 2664/3/1K Series Anne Talbot's Recipe Books Series

Transcription of 2664/3/1K Series Anne Talbot’s recipe books Series Introduction Table of Contents Transcription of 2664/3/1K Series Anne Talbot’s recipe books ........................................ 1 Series Introduction ............................................................................................................. 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 2 The Collection ............................................................................................................................ 2 Documents in the Series / Introduction / Appendixes ................................................................ 2 Talbot Family ............................................................................................................................. 4 Sharington Talbot ......................................................................................................................................... 4 Sir Gilbert Talbot (c.1606 – 1695) ................................................................................................................. 4 Sir John Talbot (1630 – 1714) and Anne Talbot (1665 – 1720) ..................................................................... 4 Conventions used in the transcription ........................................................................................ 6 For example ................................................................................................................................................. -

Carlquist Lloyd Hyde Thesis 2010.Pdf

1 Introduction As the Colonial Revival reached its zenith in the 1920s, collecting American antiques evolved from nineteenth-century relic hunting into an emerging field with its own scholarship, trade practices, and social circles. The term “Americana” came to refer to fine and decorative arts created or consumed in early America. A new type of Americana connoisseurs collected such objects to furnish idealized versions of America’s past in museums and private homes. One such Americana connoisseur was Maxim Karolik, a Russian-born tenor who donated to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston one of the most celebrated collections of American paintings, prints, and decorative arts. A report about the collection’s 1941 museum opening described how “connoisseurs looked approvingly” at the silver, “clucked with admiration” over the Gilbert Stuart portraits, and turned “green-eyed at the six-shell Newport desk-and-bookcase.”1 Karolik began collecting antiques in the 1920s, adding to those that had been inherited by Martha Codman Karolik, his “Boston Brahmin” wife. His appetite for Americana grew until he became one of the 1930s’ principal patrons, considered second only to Henry Francis du Pont. He scoured auction houses, galleries, showrooms, and small shops. Karolik loved the chase and consorting with dealers. He enjoyed haggling over prices despite his wife’s substantial fortune.2 1 “Art: Boston’s Golden Maxim,” Time (December 22, 1941). 2 Frieda Schmutzler (of Katrina Kipper’s Queen Anne Cottage), Oral History, May 26, 1978, Winterthur Archives. See also Carol Troyen, “The Incomparable Max: Maxim Karolik and the Taste for American Art,” American Art 7, n 3 (Summer 1993): 65-87.