A Sampling of Uncommon Decoration by Montgomery Artists & Artisans Past & Present

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 2021.Indd

Search Press Ltd August 2021 The Complete Book of patchwork, Quilting & Appliqué by Linda Seward www.searchpress.com/trade SEARCH PRESS LIMITED The world’s finest art and craft books ADVANCE INFORMATION Drawing - A Complete Guide: Nature Giovanni Civardi Publication 31st August 2021 Price £12.99 ISBN 9781782218807 Format Paperback 218 x 152 mm Extent 400 pages Illustrations 960 Black & white illustrations Publisher Search Press Classification Drawing & sketching BIC CODE/S AFF, WFA SALES REGIONS WORLD Key Selling Points Giovanni Civardi is a best-selling author and artist who has sold over 600,000 books worldwide No-nonsense advice on the key skills for drawing nature – from understanding perspective to capturing light and shade Subjects include favourites such as country scenes, flowers, fruit, animals and more Perfect book for both beginner and experienced artists looking for an inspirational yet informative introduction to drawing natural subjects This guide is bind-up of seven books from Search Press’s successful Art of Drawing series: Drawing Techniques; Understanding Perspective; Drawing Scenery; Drawing Light & Shade; Flowers, Fruit & Vegetables; Drawing Pets; and Wild Animals. Description Learn to draw the natural world with this inspiring and accessible guide by master-artist Giovanni Civardi. Beginning with the key drawing methods and essential materials you’ll need to start your artistic journey, along with advice on drawing perspective as well as light and shade, learn to sketch country scenes, fruit, vegetables, animals and more. Throughout you’ll find hundreds of helpful and practical illustrations, along with stunning examples of Civardi’s work that exemplify his favourite techniques for capturing the natural world. -

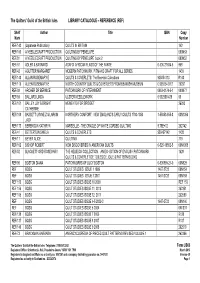

Reference (Ref)

The Quilters’ Guild of the British Isles LIBRARY CATALOGUE – REFERENCE (REF) Shelf Author Title ISBN Copy Mark Number REF/142 (Japanese Publication) QUILTS IN BRITAIN 142 REF/163 A NEEDLECRAFT PRODUCTION QUILTING BY PENELOPE 000N53 REF/81 A NEEDLECRAFT PRODUCTION QUILTING BY PENELOPE book 2 000N52 REF/61 ADLER & BARNARD ASAFO! AFRICAN FLAGS OF THE FANTE 0-500-27684-6 968 REF/42 AGUTTER MARGARET MODERN PATCHWORK PITMANS CRAFT FOR ALL SERIES 1439 REF/140 ALLAN ROSEMARY E QUILTS & COVERLETS: The Beamish Collections 905054113 R140 REF/116 ALLEN ROSEMARY E NORTH COUNTRY QUILTS & COVERLETS FROM BEAMISH MUSEUM 0 905054 03 2 26297 REF/93 ARCHER DR BERNICE PATCHWORK OF INTERNMENT 0953-0174-5-1 000N77 REF/69 BALLARD LINDA ULSTER NEEDLEWORK 0 902588 435 99 REF/101 BALLEY JOY & BRIGHT MEMENTO FOR BRIDGET 26293 CATHERINE REF/109 BASSETT LYNNE Z & LARKIN NORTHERN COMFORT: NEW ENGLAND'S EARLY QUILTS 1780-1850 1-55853-655-8 00N1056 JACK REF/173 BERENSON KATHRYN MARSEILLE - THE CRADLE OF WHITE CORDED QUILTING 9.78E+12 262742 REF/41 BETTERTON SHIELA QUILTS & COVERLETS 950497142 1438 REF/17 BEYER ALICE QUILTING 710 REF/102 BISHOP ROBERT NEW DISCOVERIES IN AMERICAN QUILTS 0-525-16552-5 00N1055 REF/52 BLACKETT-ORD ROSEMARY THE HELBECK COLLECTION . AN EXHIBITION OF ENGLISH PATCHWORK 1629 QUILTS & COVERLET DE TOILES DE JOUE & PATTERN BOOKS REF/95 BOSTON DIANA PATCHWORKS OF LUCY BOSTON 0-905899-21-0 00N629 REF BQSG QUILT STUDIES ISSUE 1 1999 1467-2723 00N154 REF BQSG QUILT STUDIES ISSUE 3 2001 1467-2723 00N158 REF 153 BQSG QUILT STUDIES ISSUE 10 2009 REF 153 -

American Quilts

CATALOGUE AMERICAN QUILTS 1819 -- 1948 From the Museum Collection Compiled by Mildred Davison The Art Institute of Chicago, Department of Decorative Arts Exhibition April 20, 1959 - October 19, 1959 AMERICAN QUILTS 1819 - 1948, FROM THE MUSEUM COLLECTION The Art Institute of Chicago, April Z0 1 1959 --October 19, 1959 Although patchwork has been known and practised since ancient times, nowhere has it played such a distinctive and characteristic part as in the bed covers of early America where it added the finishing touches to eighteenth and nineteenth century bed chambers. The term "patchwork" is used indiscriminately to include the pieced and the appliqued quilts. Pieced quilts are generally geometric in pattern being a combination of small patches sewn together with narrow seams. The simplest form of pieced pattern is the eight-pointed star formed of diamond shaped patches. This was known as the Star of Le Moyne, named in honor of Jean Baptiste Le Moyne who founded New Orleans in 1718, and from it was developed numerous others including all of the lily and tulip designs. In applique quilts, pieces were cut to form the pattern and appliqued to a back - ground material with fine hemming or embroidery stitches, a method which gave a wider scope for patterns. By 1850, applique quilts reached such a degree of elaboration that many years were spent in their making and they were often intend ed for use as counterpanes. The most common fabrics for quilts were plain and figured calicoes and chintzes with white muslin..., The source of these materials in early times and pioneer communities was the scrap bag. -

Patricia Cox Crews

1 PATRICIA COX CREWS The University of Nebraska-Lincoln Department of Textiles, Merchandising & Fashion Design Lincoln, Nebraska 68583-0802 Office: (402) 472-6342 Home: (402) 488-8371 EDUCATION Degree Programs 1971 B.S., Virginia Tech, Fashion Design and Merchandising. 1973 M.S., Florida State University, Textile Science. 1984 Ph.D., Kansas State University, Textile Science and Conservation. Other Education 1982 Organic Chemistry for Conservation, Smithsonian Institute Certificate of Training (40 hours). 1985 Historic Dyes Identification Workshop, Smithsonian Conservation Analytical Lab, Washington, D.C. 1990 Colorimetry Seminar, Hunter Associates, Kansas City, MO. 1994 Applied Polarized Light Microscopy, McCrone Research Institute, Chicago, IL. 2007 Museum Leadership Institute, Getty Foundation, Los Angeles, CA. PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE 1984- University of Nebraska-Lincoln, Willa Cather Professor of Textiles, 2003-present; Founding Director Emeritus, International Quilt Study Center & Museum, 1997- 2013; Professor, 1996-present; Acting Chair, Dept. of Textiles, Clothing & Design, 2000; Chair, Interdisciplinary Museum Studies Program, 1995-1997; Associate Professor, 1989-1996; Assistant Professor, 1984-89. Courses taught: Textile History, Care and Conservation of Textile Collections, Artifact Analysis, Textile Dyeing, and Advanced Textiles. 1982 Summer Internship. Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of American History-Division of Textiles. 1977-84 Kansas State University, Manhattan, Kansas, Instructor of Textiles. 1976-77 Bluefield State College, Bluefield, West Virginia, Instructor of Textiles and Weaving. 1975 Virginia Western Community College, Roanoke, Virginia, Instructor of Textiles and Weaving. 1973-74 Oregon State University, Corvallis, Oregon, Instructor of Textiles. HONORS AND AWARDS 2013 Reappointed to Willa Cather Professorship in recognition of distinguished scholarship. 2009 University of Nebraska, College of Education & Human Sciences Faculty Mentoring Award. -

Come in to Bernina, There's Something for You!

©2003 Bernina of America Special financing, great prices* and a sweepstakes, too! Come in to Bernina, there’s something for you! November 10 through December 31, you’ll also receive a free gift with select purchases at your Bernina Dealer. Plus, visit berninausa.com to see the holiday catalog and enter the exciting sweepstakes––you could win a $5,000 Bernina shopping spree! So, hop in your holiday sleigh and hurry in to your Bernina Dealer today. No one supports the creative sewer like a Bernina Dealer. • www.berninausa.com *At participating dealers ISSUE 8 Asian Styling, Page 4 Snap, Stitch & Scrap Page 12 2003 Bernina® Fashion Show: Fantasy, Page 20 WHO WE ARE... MEADOWBROOK TABLE MEDALLION FANTASTIC FELINES VEST Meet the talented staff and stitchers who Reprinted from the Benartex Fat Quarterly, this A creative combination of colorful embroidery, contribute tips, project ideas, and stories to table decoration by Gayle Camargo is perfect hand-dyed silk noil, and black and white prints. Through the Needle. for fall and winter, and easy to assemble. Page 18 Page 2 Page 10 THE 2003 BERNINA® FASHION SHOW: FANTASY BERNINA® NEWS BERNINA® FASHION: BLACK ROSE BLOUSE Take a peek at some of this year’s “fantastic” ® Be as creative as you want to be! From Don’t have time to stitch a special garment? entries at the BERNINA Fashion Show – these scrapbooks to patchwork vests, baseball caps to Start with a purchased linen blouse, then add garments are truly a fantasy come true. wearable art, BERNINA® sewing machines and embellishments as shown in this article. -

Proceedings of the Textile Society of America 17Th Biennial Symposium, October 15-17, 2020--Full Program with Abstracts & Bios

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings Textile Society of America 10-2020 Hidden Stories/Human Lives: Proceedings of the Textile Society of America 17th Biennial Symposium, October 15-17, 2020--Full Program with Abstracts & Bios Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/tsaconf Part of the Art and Materials Conservation Commons, Art Practice Commons, Fashion Design Commons, Fiber, Textile, and Weaving Arts Commons, Fine Arts Commons, and the Museum Studies Commons This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Textile Society of America at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. WELCOME PAGE Be Part of the Conversation Tag your posts on social media #TSAHiddenStoriesHumanLives #TSA2020 Like us on Facebook: @textilesocietyofamerica Follow us on Instagram: @textilesociety Attendee Directory The attendee directory is available through Crowd Compass If you have any questions, please contact Caroline Hayes Charuk: [email protected]. Please note that the information published in this program and is subject to change. Please check textilesocietyofamerica.org for the most up-to-date infor- mation. TABLE OF CONTENTS About the Symposium . 1 The Theme .......................................................1 Symposium Chairs ................................................1 Symposium Organizers . .2 Welcome from TSA President, Lisa Kriner . 4 Donors & Sponsors . 8 Symposium Schedule at a Glance . 11 Welcome from the Symposium Program Co-Chairs . 12 Keynote & Plenary Sessions . 14 Sanford Biggers..................................................14 Julia Bryan-Wilson................................................15 Jolene K. Rickard.................................................16 Biennial Symposium Program . -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright materiai had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one exposure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6” x 9” black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. Bell & Howell Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road, Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. "IN THEMSELVES A TEXTILE MUSEUM": THE FORMATION OF THE TEXTILE COLLECTION AT THE H.F. -

Marketing Products from the Art of Weaving Jamdani and Jute Diversified Products (JDP) of Bangladesh in Canada

Promoting specialty textile and fabrics: Marketing products from the art of weaving Jamdani and Jute diversified products (JDP) of Bangladesh in Canada Submitted by Nawshad Ali Khan CEO, JOYA and Subarno Rekha 620, Shahin Bagh, Lane-6 Tejgaon, Daka-1215 Dr. Rafat Alam Assistant Professor and Discipline Coordinator MacEwan University, Edmonton, Alberta [email protected] (corresponding author) Submitted to Trade Facilitation of Office Canada (TFO Canada) and International Development Research Center (IDRC) September, 2016 Abstract Increased free trade and market-based policies have opened the door for export-oriented growth for developing countries. ‘But the development of trade relationships with new export markets is complex and needs more than a general privatization and liberalization policy (Keegan, 1995)’, especially for the specialty textile products that are produced by small firms in the cottage industry which overwhelmingly employ rural, low-income and female workers. Many domestic and international market obstacles make it difficult for these unique products to be exported. This paper looks into the cases of two specialty textile products from Bangladesh - Jamdani and Jute diversified products (JDP) and investigates the export problems perceived by the sectors. The paper finds that JDP is export ready and well supported by government policies and institutions. The sector also has enough export experiences in European Union (EU) and North American markets. However, the sector faces fierce competition domestically and from Indian and Chinese firms. The sector also lacks in product design and has some weaknesses in quality. A vertical network is necessary to exchange information and cooperate in quality control, design and product development among the local trade association, government supporting institutions, local firms and designers, and foreign buyers and designers. -

Santa Clarita Valley Quilt Guild

Publisher: Melissa Nilsen February 2021 Volume 32 – Issue 02 SANTA CLARITA VALLEY QUILT GUILD Our mission is to stimulate an interest in quilts, to promote and advance the art of quilt making, to conduct educational programs and services in the design techniques and preservation of quilts and quilt making; and to promote quilting in philanthropic endeavors. PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE History of Quilting, continued… As mentioned last month, early American settlers could not afford to simply discard things when they wore out; necessity required they carefully use their resources. Therefore, when blankets became worn, they were patched, combined with other blankets, or used as filler between other blankets. These were not carefully constructed heirlooms, rather they were functional items for the sole purpose of keeping people warm. Only in later years, when fabrics were being manufactured in America and were more affordable, freeing women from the work of making their own yarns and fabrics, did the more artistic type of quilting become more widespread. In the 100 years between 1750 and 1850, thousands of American quilts were pieced and patched, and many of them are preserved. Many of these quilts were so elaborate that years were spent making and quilting them (remember Marguerite Heinisch from 2019?). It is no wonder they are cherished as precious heirlooms and occupy honored places in homes and museums (Note: The Smithsonian Institute has a collection of 500 quilts that covers a 250- year time period – I recommend a visit!). Those early quilts provide a glimpse into the history of quilting as well as the history of the United States. -

Anna Von Mertens Discipline: Visual Arts (Quilting)

EDUCATOR GUIDE Story Theme: Needlework Subject: Anna Von Mertens Discipline: Visual Arts (Quilting) SECTION I - OVERVIEW ......................................................................................................................2 EPISODE THEME SUBJECT CURRICULUM CONNECTIONS OBJECTIVE INSTRUCTIONAL STRATEGIES INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES EQUIPMENT NEEDED MATERIALS NEEDED INTELLIGENCES ADDRESSED SECTION II – CONTENT/CONTEXT ..................................................................................................3 CONTENT OVERVIEW THE BIG PICTURE RESOURCES – TEXTS RESOURCES – WEB SITES BAY AREA RESOURCES - CLASSES BAY AREA RESOURCES – TEXTILE COLLECTIONS SECTION III – VOCABULARY.............................................................................................................8 SECTION IV – ENGAGING WITH SPARK ...................................................................................... 10 Quilts in the MATRIX project series by Anna Von Mertens on exhibition at the Berkeley Art Museum in 2003. Reprinted with permission from http://www.annavonmertens.com. Photo: Jean‐Michel Addor. SECTION I - OVERVIEW EPISODE THEME INSTRUCTIONAL OBJECTIVES Needlework To enable students to ‐ Understand the development of personal works of SUBJECT art and their relationships to social themes and Anna Von Mertens ideas, abstract concepts, and the history of art. Develop basic observational drawing and/or GRADE RANGES painting skills. K‐12 & Post‐secondary Develop visual, written, listening and speaking skills through looking -

Enhancing Textile Practice

CLIP CETL: enhancing textile practice Contents 1 FASHION Resurface, reshape, and restructure Manipulation 2 Enriching, EMBROIDERY embellishing, and adorning INTRODUCTORY STUDIES Adding 3 Bedecked, bedazzled, and bejeweled Beading 4 Displacing, extracting, and distressing Subtracting 5 Constructing creating, and joining Forming FASHION DESIGN TECHNOLOGY Foreword Glossary About this CD Cover 1 2 3 4 5 Resurface, Enriching, Bedecked, Displacing, Constructing reshape, and embellishing, and bedazzled, and extracting, and creating, and restructure adorning bejeweled distressing joining Manipulation Adding Beading Subtracting Forming Gathering Appliqué Tambour Perforating Machine shirring and Couching: beading Cutwork made lace puckering ribbons, cords, Hand Découpé Weaving/ Pleating braids, objects beading Interlacing and tucking Reverse Stitching French applique Piecing and Smocking beading patching Bonding, Drawn thread Quilting trapping, Beaded Needle layering and fringes Pulled work punching slashing Beaded Knotting cord Beaded Tassel Index a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z Contents Resurface, reshape, and restructure Manipulation 1 Resurface, reshape, and Fabric manipulation can be considered as including any technique that restructure reshapes the surface of the fabric. These processes change both the look Manipulation and the feel of the material. They embrace the folding techniques of Introduction pleating, smocking and tucking, the crushing techniques of gathering, shirring and puckering and the raised relief of quilting. These techniques can either be used in isolation or combined to reconstruct or to reshape a 2 surface. Most of the techniques have considerable historical information Enriching, available for research both in written form and in examples in collections. -

DETAILED SYLLABUS for DISTANCE EDUCATION Bachelor

DETAILED SYLLABUS FOR DISTANCE EDUCATION Under Graduate Degree Program Bachelor of Science in Fashion Design (BSCFD) (SEMESTER SYSTEM) Course Title : BSCFD Duration : 03 Years (Semester System) Total Degree Marks : 4800 1. Program Structure First Semester COURSE TITLE Paper Code MARKS THEORY PRACTICAL TOTAL MARKS INTERNA EXTERNA INTERNA EXTERNA L L L L Basic Fashion Concepts BSCFD/S/110 40 60 40 60 200 Fundamentals of Textiles BSCFD/S/120 40 60 40 60 200 Effective Communication Skill BSCFD/S/130 40 60 NA NA 100 Introduction to Yarn Craft BSCFD/S/140 40 60 NA NA 100 Computer Fundamentals BSCFD/S/150 40 60 40 60 200 Second Semester COURSE TITLE Paper Code MARKS THEORY PRACTICAL TOTAL MARKS INTERNA EXTERNA INTERNA EXTERNA L L L L Elements of Design BSCFD/S/210 40 60 40 60 200 Introduction to Advanced Multimedia BSCFD/S/220 40 60 40 60 200 Basic of Pattern Making BSCFD/S/230 40 60 40 60 200 Study of Sewing Technology BSCFD/S/240 40 60 40 60 200 Third Semester COURSE TITLE Paper Code MARKS THEORY PRACTICAL TOTAL INTERNA EXTERNA INTERNA EXTERNA MARKS L L L L Concepts of Pattern Making and Stitching BSCFD/S/310 40 60 40 60 200 Yarns to Fabrics BSCFD/S/320 40 60 40 60 200 Classification of Fashion Areas BSCFD/S/330 40 60 40 60 200 Fashion Illustration BSCFD/S/340 40 60 40 60 200 Fourth Semester COURSE TITLE Paper Code MARKS THEORY PRACTICAL TOTAL MARKS INTERNA EXTERNA INTERNA EXTERNA L L L L Fabric Preparation for Consumers BSCFD/S/410 40 60 40 60 200 Basics of Embroidery BSCFD/S/420 40 60 NA NA 100 Import & Export Procedure BSCFD/S/430 40 60