Carlquist Lloyd Hyde Thesis 2010.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RETROSPECTIVE BOOK REVIEWS by Esley Hamilton, NAOP Board Trustee

Field Notes - Spring 2016 Issue RETROSPECTIVE BOOK REVIEWS By Esley Hamilton, NAOP Board Trustee We have been reviewing new books about the Olmsteds and the art of landscape architecture for so long that the book section of our website is beginning to resemble a bibliography. To make this resource more useful for researchers and interested readers, we’re beginning a series of articles about older publications that remain useful and enjoyable. We hope to focus on the landmarks of the Olmsted literature that appeared before the creation of our website as well as shorter writings that were not intended to be scholarly works or best sellers but that add to our understanding of Olmsted projects and themes. THE OLMSTEDS AND THE VANDERBILTS The Vanderbilts and the Gilded Age: Architectural Aspirations 1879-1901. by John Foreman and Robbe Pierce Stimson, Introduction by Louis Auchincloss. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991, 341 pages. At his death, William Henry Vanderbilt (1821-1885) was the richest man in America. In the last eight years of his life, he had more than doubled the fortune he had inherited from his father, Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt (1794-1877), who had created an empire from shipping and then done the same thing with the New York Central Railroad. William Henry left the bulk of his estate to his two eldest sons, but each of his two other sons and four daughters received five million dollars in cash and another five million in trust. This money supported a Vanderbilt building boom that remains unrivaled, including palaces along Fifth Avenue in New York, aristocratic complexes in the surrounding countryside, and palatial “cottages” at the fashionable country resorts. -

A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History Is a Publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service

Published online 2016 www.nps.gov/subjects/tellingallamericansstories/lgbtqthemestudy.htm LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History is a publication of the National Park Foundation and the National Park Service. We are very grateful for the generous support of the Gill Foundation, which has made this publication possible. The views and conclusions contained in the essays are those of the authors and should not be interpreted as representing the opinions or policies of the U.S. Government. Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute their endorsement by the U.S. Government. © 2016 National Park Foundation Washington, DC All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted or reproduced without permission from the publishers. Links (URLs) to websites referenced in this document were accurate at the time of publication. PRESERVING LGBTQ HISTORY The chapters in this section provide a history of archival and architectural preservation of LGBTQ history in the United States. An archeological context for LGBTQ sites looks forward, providing a new avenue for preservation and interpretation. This LGBTQ history may remain hidden just under the ground surface, even when buildings and structures have been demolished. THE PRESERVATION05 OF LGBTQ HERITAGE Gail Dubrow Introduction The LGBTQ Theme Study released by the National Park Service in October 2016 is the fruit of three decades of effort by activists and their allies to make historic preservation a more equitable and inclusive sphere of activity. The LGBTQ movement for civil rights has given rise to related activity in the cultural sphere aimed at recovering the long history of same- sex relationships, understanding the social construction of gender and sexual norms, and documenting the rise of movements for LGBTQ rights in American history. -

Museum of M()Dern Art , Su M Mer

'MUSEUM OF M()DERN ART . ~ , SU M MER E X H I~B"I·T;'I-O·N .. «' - ....,.- '"' ~'''", . .,~.~ ". , -, ,~ _ '\ c - --7'-"-....;:;.:..,:· ........ ~~., - ", -,'" ,""" MoMAExh_0007_MasterChecklist , , . ,. • •• ' ,A· . -" . .t, ' ." . , , ,.R'ET-ROSPECTIVE .. , . .... ~,~, , ....., , .' ~ ,,"• ~, ~.. • • JUNE 1930 SEPTEMBER 730 FIFTH AVENUE · NEW YORK J ( - del SCULPTURE : , Rudolf Bdling I MAX SCHMELING (Bronze) Born, 1886 Berlin. Collection Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of Alfred Flechtheim, Berlin CItarl~s D~spiau 2. HEADOFMARIALANI(Bro11ze) Born 1874. .. Collection Museum of Modern Art, New Yark Mont de Marsan, France. Gift of Miss L. P. Bliss WilIt~lm L~Itmf:,ruck >0. 0S~FIGUREOFWO¥AN(Stollt) PREVIOUSLY EXHIBITED Born 1881. Germany. Private Collection, New York Died 1919. 4 STANDING WOMAN (Bro11ze) PREVIOUSLY EXHIBITED Collection Museum of Modern Art, New York MoMAExh_0007_MasterChecklist Gifr of Stephen C. Clark Aristid~ MaiUo! 5 DESIRE (Plaster relief) PREVIOUSLY EXHIBITED Born 1861 in southern France. Collection Museum of Modern Arr, New York Gift of the Sculptor. 6 SPRING (Plaster) PREVIOUSLY EXHIBITED Collection Museum of Modern Art, New York Gifr of the Sculptor. 7 SUMMER (Plaster) PREVIOUSLY EXHIBITED Collection Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of the Sculptor. 8 TORSO OF A YOUNG WOMAN (Bro11ze) PREVIOUSLY EXHIBITED Collection Museum of Modern Art, New York Gift of A. Conger Goodyear PAINTING P~t~rBlum~ ~ 0 , ~.:s-o 9 PARADE PREVIOUSLY EXHIDITED Born 1906, Russia. Private Collection, New York G~org~s Braqu~ /:5 0 • b0 '3 10 LE COMPOTIER ET LA SERVIETTE Born 1881. Argenteuil. " Collection Frank Crowninshield, New York 0 , " 0 '" II STIlL LIFE I'?> J Collection Frank Crowninshield, New York ~ 0 bUb 12. PEARS, PIPE AND PITCHER ~ I Collection Phillips Memorial Gallery, Washington 3 I L 13D,iQa,13 FALLEN TREE PREVIOUSLY EXHIBITED Born 1893, Ashtabula Harbor, Ohio. -

City of Gloucester Community Preservation Committee

CITY OF GLOUCESTER COMMUNITY PRESERVATION COMMITTEE BUDGET FORM Project Name: Masonry and Palladian Window Preservation at Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House Applicant: Historic New England SOURCES OF FUNDING Source Amount Community Preservation Act Fund $10,000 (List other sources of funding) Private donations $4,000 Historic New England Contribution $4,000 Total Project Funding $18,000 PROJECT EXPENSES* Expense Amount Please indicate which expenses will be funded by CPA Funds: Masonry Preservation $13,000 CPA and Private donations Window Preservation $2,200 Historic New England Project Subtotal $15,200 Contingency @10% $1,520 Private donations and Historic New England Project Management $1,280 Historic New England Total Project Expenses $18,000 *Expenses Note: Masonry figure is based on a quote provided by a professional masonry company. Window figure is based on previous window preservation work done at Beauport by Historic New England’s Carpentry Crew. Historic New England Beauport, The Sleeper-McCann House CPA Narrative, Page 1 Masonry Wall and Palladian Window Repair Historic New England respectfully requests a $10,000 grant from the City of Gloucester Community Preservation Act to aid with an $18,000 project to conserve a portion of a masonry wall and a Palladian window at Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House, a National Historic Landmark. Project Narrative Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House Beauport, the Sleeper-McCann House, was the summer home of one of America’s first professional interior designers, Henry Davis Sleeper (1878-1934). Sleeper began constructing Beauport in 1907 and expanded it repeatedly over the next twenty-seven years, working with Gloucester architect Halfdan M. -

2010-2011 Newsletter

Newsletter WILLIAMS G RADUATE PROGRAM IN THE HISTORY OF A RT OFFERED IN COLLABORATION WITH THE CLARK ACADEMIC YEAR 2010–11 Newsletter ••••• 1 1 CLASS OF 1955 MEMORIAL PROFESSOR OF ART MARC GOTLIEB Letter from the Director Greetings from Williamstown! Our New features of the program this past year include an alumni now number well over 400 internship for a Williams graduate student at the High Mu- going back nearly 40 years, and we seum of Art. Many thanks to Michael Shapiro, Philip Verre, hope this newsletter both brings and all the High staff for partnering with us in what promises back memories and informs you to serve as a key plank in our effort to expand opportuni- of our recent efforts to keep the ties for our graduate students in the years to come. We had a thrilling study-trip to Greece last January with the kind program academically healthy and participation of Elizabeth McGowan; coming up we will be indeed second to none. To our substantial community of alumni heading to Paris, Rome, and Naples. An ambitious trajectory we must add the astonishingly rich constellation of art histori- to be sure, and in Rome and Naples in particular we will be ans, conservators, and professionals in related fields that, for a exploring 16th- and 17th-century art—and perhaps some brief period, a summer, or on a permanent basis, make William- sense of Rome from a 19th-century point of view, if I am al- stown and its vicinity their home. The atmosphere we cultivate is lowed to have my way. -

A Mechanism of American Museum-Building Philanthropy

A MECHANISM OF AMERICAN MUSEUM-BUILDING PHILANTHROPY, 1925-1970 Brittany L. Miller Submitted to the faculty of the University Graduate School in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in the Departments of History and Philanthropic Studies, Indiana University August 2010 Accepted by the Faculty of Indiana University, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ____________________________________ Elizabeth Brand Monroe, Ph.D., J.D., Chair ____________________________________ Dwight F. Burlingame, Ph.D. Master’s Thesis Committee ____________________________________ Philip V. Scarpino, Ph.D. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the same way that the philanthropists discussed in my paper depended upon a community of experienced agents to help them create their museums, I would not have been able to produce this work without the assistance of many individuals and institutions. First, I would like to express my thanks to my thesis committee: Dr. Elizabeth Monroe (chair), Dr. Dwight Burlingame, and Dr. Philip Scarpino. After writing and editing for months, I no longer have the necessary words to describe my appreciation for their support and flexibility, which has been vital to the success of this project. To Historic Deerfield, Inc. of Deerfield, Massachusetts, and its Summer Fellowship Program in Early American History and Material Culture, under the direction of Joshua Lane. My Summer Fellowship during 2007 encapsulated many of my early encounters with the institutional histories and sources necessary to produce this thesis. I am grateful to the staff of Historic Deerfield and the thirty other museums included during the fellowship trips for their willingness to discuss their institutional histories and philanthropic challenges. -

John Singer Sargent's British and American Sitters, 1890-1910

JOHN SINGER SARGENT’S BRITISH AND AMERICAN SITTERS, 1890-1910: INTERPRETING CULTURAL IDENTITY WITHIN SOCIETY PORTRAITS EMILY LOUISA MOORE TWO VOLUMES VOLUME 1 PH.D. UNIVERSITY OF YORK HISTORY OF ART SEPTEMBER 2016 ABSTRACT Began as a compositional analysis of the oil-on-canvas portraits painted by John Singer Sargent, this thesis uses a selection of those images to relate national identity, cultural and social history within cosmopolitan British and American high society between 1890 and 1910. Close readings of a small selection of Sargent’s portraits are used in order to undertake an in-depth analysis on the particular figural details and decorative elements found within these images, and how they can relate to nation-specific ideologies and issues present at the turn of the century. Thorough research was undertaken to understand the prevailing social types and concerns of the period, and biographical data of individual sitters was gathered to draw larger inferences about the prevailing ideologies present in America and Britain during this tumultuous era. Issues present within class and family structures, the institution of marriage, the performance of female identity, and the formulation of masculinity serve as the topics for each of the four chapters. These subjects are interrogated and placed in dialogue with Sargent’s visual representations of his sitters’ identities. Popular images of the era, both contemporary and historic paintings, as well as photographic prints are incorporated within this analysis to fit Sargent’s portraits into a larger art historical context. The Appendices include tables and charts to substantiate claims made in the text about trends and anomalies found within Sargent’s portrait compositions. -

A Finding Aid to the Elizabeth Mccausland Papers, 1838-1995, Bulk 1920-1960, in the Archives of American Art

A Finding Aid to the Elizabeth McCausland Papers, 1838-1995, bulk 1920-1960, in the Archives of American Art Jennifer Meehan and Judy Ng Funding for the processing and digitization of this collection was provided by the Terra Foundation for American Art April 12, 2006 Archives of American Art 750 9th Street, NW Victor Building, Suite 2200 Washington, D.C. 20001 https://www.aaa.si.edu/services/questions https://www.aaa.si.edu/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical Note............................................................................................................. 3 Scope and Content Note................................................................................................. 4 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 5 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 5 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 7 Series 1: Personal Papers, 1838, 1920-1951.......................................................... 7 Series 2: Correspondence, 1923-1960.................................................................. 10 Series 3: General -

In 193X, Constance Rourke's Book American Humor Was Reviewed In

OUR LIVELY ARTS: AMERICAN CULTURE AS THEATRICAL CULTURE, 1922-1931 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Jennifer Schlueter, M.A. ***** The Ohio State University 2007 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Thomas Postlewait, Adviser Professor Lesley Ferris Adviser Associate Professor Alan Woods Graduate Program in Theatre Copyright by Jennifer Schlueter c. 2007 ABSTRACT In the first decades of the twentieth century, critics like H.L. Mencken and Van Wyck Brooks vociferously expounded a deep and profound disenchantment with American art and culture. At a time when American popular entertainments were expanding exponentially, and at a time when European high modernism was in full flower, American culture appeared to these critics to be at best a quagmire of philistinism and at worst an oxymoron. Today there is still general agreement that American arts “came of age” or “arrived” in the 1920s, thanks in part to this flogging criticism, but also because of the powerful influence of European modernism. Yet, this assessment was not, at the time, unanimous, and its conclusions should not, I argue, be taken as foregone. In this dissertation, I present crucial case studies of Constance Rourke (1885-1941) and Gilbert Seldes (1893-1970), two astute but understudied cultural critics who saw the same popular culture denigrated by Brooks or Mencken as vibrant evidence of exactly the modern American culture they were seeking. In their writings of the 1920s and 1930s, Rourke and Seldes argued that our “lively arts” (Seldes’ formulation) of performance—vaudeville, minstrelsy, burlesque, jazz, radio, and film—contained both the roots of our own unique culture as well as the seeds of a burgeoning modernism. -

Annual Report 2005°2006

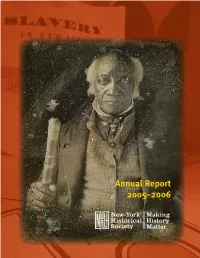

"OOVBM3FQPSU ° #PBSEPG5SVTUFFT Roger Hertog, Chair 4FOJPS4UBGG Richard Gilder, Co-Chair, Louise Mirrer Laura Smith Executive Committee President and Chief Executive Officer Senior Vice President for Institutional Nancy Newcomb, Co-Chair, Stephanie Benjamin Advancement and Strategic Initiatives Executive Committee Executive Vice President and Janine Jaquet Chief Operating Officer Vice President for Development and Louise Mirrer, President and CEO Linda S. Ferber Executive Director of the Chairman’s Vice President and Council William Beekman Director of the Museum Andrew Buonpastore Judith Roth Berkowitz Jean W. Ashton Vice President for Operations David Blight Vice President and Director Richard Shein Ric Burns of the Library Chief Financial Officer James Chanos Laura Washington Roy Eddey Craig Cogut Vice President for Communications Director of Museum Administration Elizabeth B. Dater Barbara Knowles Debs 8MJJER]7XYHMSW8VYQTIX'VIITIVWLEHISRQSWEMG 'SZIV9RMHIRXMJMIHTLSXSKVETLIV'EIWEV%7PEZI Joseph A. DiMenna FEWIG+MJXSJ(V)KSR2IYWXEHX (EKYIVVISX]TI'SPPIGXMSRSJXLI2I[=SVO Charles E. Dorkey, III 2 ,MWXSVMGEP7SGMIX]0MFVEV] Henry Louis Gates, Jr. Richard Gelfond Kenneth T. Jackson Joan C. Jakobson David R. Jones Patricia Klingenstein Sidney Lapidus Lewis E. Lehrman Alan Levenstein Glen S. Lewy Tarky Lombardi, Jr. Sarah E. Nash Russell Pennoyer Charles M. Royce Thomas A. Saunders, III Pam B. Schafler Benno C. Schmidt, Jr. Bernard Schwartz Emanuel Stern Ernest Tollerson Sue Ann Weinberg Byron R. Wien Hope Brock Winthrop )POPSBSZ5SVTUFFT Patricia Altschul Leila Hadley Luce 'SPNUIF$P$IBJST Christine Quinn and Betsy Gotbaum, undisputed “first ladies” of New York City government, at our Strawberry Luncheon this year. Lynn Sherr, award-winning correspondent for ABC’s 20/20, spoke eloquently on the origins and significance of the song America the Beautiful and the backgrounds of its authors. -

Benjamin C. Bradlee

Benjamin C. Bradlee: An Inventory of His Papers at the Harry Ransom Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Bradlee, Benjamin C., 1921-2014 Title: Benjamin C. Bradlee Papers Dates: 1921-2013 Extent: 185 document boxes, 2 oversize boxes (osb) (77.7 linear feet), 1 galley file (gf) Abstract: The Benjamin C. Bradlee Papers consist of memos, correspondence, manuscript drafts, desk diaries, transcripts of interviews and speeches, clippings, legal and financial documents, photographs, notes, awards and certificates, and printed materials. These professional and personal records document Bradlee’s career at Newsweek and The Washington Post, the composition of written works such as A Good Life and Conversations with Kennedy, and Bradlee’s post-retirement activities. Call Number: Manuscript Collection MS-05285 Language: English and French Access: Open for research. Researchers must register and agree to copyright and privacy laws before using archival materials. Some materials are restricted due to condition, but facsimiles are available to researchers. Administrative Information Acquisition: Purchases, 2012 (12-05-003-D, 12-08-019-P) and Gift, 2015 (15-12-002-G) Processed by: Ancelyn Krivak, 2016 Repository: The University of Texas at Austin, Harry Ransom Center Bradlee, Benjamin C., 1921-2014 Manuscript Collection MS-05285 Biographical Sketch Benjamin Crowninshield Bradlee was born in Boston on August 26, 1921, to Frederick Josiah Bradlee, Jr., an investment banker, and Josephine de Gersdorff Bradlee. A descendant of Boston’s Brahmin elite, Bradlee lived in an atmosphere of wealth and privilege as a young child, but after his father lost his position following the stock market crash of 1929, the family lived without servants as his father made ends meet through a series of odd jobs. -

![Papers of Clare Boothe Luce [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4480/papers-of-clare-boothe-luce-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-1694480.webp)

Papers of Clare Boothe Luce [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF

Clare Boothe Luce A Register of Her Papers in the Library of Congress Prepared by Nan Thompson Ernst with the assistance of Joseph K. Brooks, Paul Colton, Patricia Craig, Michael W. Giese, Patrick Holyfield, Lisa Madison, Margaret Martin, Brian McGuire, Scott McLemee, Susie H. Moody, John Monagle, Andrew M. Passett, Thelma Queen, Sara Schoo and Robert A. Vietrogoski Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2003 Contact information: http://lcweb.loc.gov/rr/mss/address.html Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Manuscript Division, 2003 Finding aid URL: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms003044 Latest revision: 2008 July Collection Summary Title: Papers of Clare Boothe Luce Span Dates: 1862-1988 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1930-1987) ID No.: MSS30759 Creator: Luce, Clare Boothe, 1903-1987 Extent: 460,000 items; 796 containers plus 11 oversize, 1 classified, 1 top secret; 319 linear feet; 41 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in English Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: Journalist, playwright, magazine editor, U.S. representative from Connecticut, and U.S. ambassador to Italy. Family papers, correspondence, literary files, congressional and ambassadorial files, speech files, scrapbooks, and other papers documenting Luce's personal and public life as a journalist, playwright, politician, member of Congress, ambassador, and government official. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. Personal Names Barrie, Michael--Correspondence. Baruch, Bernard M.