1. Learning the Craft

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATIONAL FILM BOARD of CANADA FEATURED at Moma

The Museum off Modern Art 50th Anniversary NO. 16 ID FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 3, 1981 DOCUMENTARY FILMS FROM THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA FEATURED AT MoMA NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA: A RETROSPECTIVE is a three-part tribute presented by The Museum of Modern Art in recog nition of NFBC's 41 years Of exceptional filmmaking. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY FILMS, running from March 26 through May 12 in the Museum's Roy and Niuta Titus Auditorium, will trace the develop ment of the documentary form at NFBC, and will be highlighted by a selection of some of the finest films directed by Donald Brittain, whose work has won wide acclaim and numerous awards. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY will get off to an auspicious start with twelve of Donald Brittain's powerful and unconventional portraits of exceptional individuals. Best known in this country for "Volcano: An Inquiry Into The Life and Death of Malcolm Lowry" (1976), Brittain brings his personal stamp of creative interpretation to such subjects as America's love affair with the automobile in "Henry Ford's America" (1976) ; the flamboyant Lord Thompson of Fleet Street (the newspaper baron who just sold the cornerstone of his empire, The London Times) in "Never A Backward Step" (1966); Norman Bethune, the Canadian poet/ doctor/revolutionary who became a great hero in China when he marched with Mao ("Bethune" 1964); and the phenomenal media hysteria sur rounding the famous quintuplets in "The Diorme Years" (1979) . "Memo randum" (1965) accompanies a Jewish glazier from Tcronto when he takes his son back to the concentration camp where he was interned, an emotion al and historical pilgrimage of strong impact and sensitivity. -

Northern Conference Film and Video Guide on Native and Northern Justice Issues

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 287 653 RC 016 466 TITLE Northern Conference Film and Video Guide on Native and Northern Justice Issues. INSTITUTION Simon Fraser Univ., Burnaby (British Columbia). REPORT NO ISBN-0-86491-051-7 PUB DATE 85 NOTE 247p.; Prepared by the Northern Conference Resource Centre. AVAILABLE FROM Northern Conference Film Guide, Continuing Studies, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada V5A 1S6 ($25.00 Canadian, $18.00 U.S. Currency). PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Adolescent Development; *American Indians; *Canada Natives; Children; Civil Rights; Community Services; Correctional Rehabilitation; Cultural Differences; *Cultural Education; *Delinquency; Drug Abuse; Economic Development; Eskimo Aleut Languages; Family Life; Family Programs; *Films; French; Government Role; Juvenile Courts; Legal Aid; Minority Groups; Slides; Social Problems; Suicide; Tribal Sovereignty; Tribes; Videotape Recordings; Young Adults; Youth; *Youth Problems; Youth Programs IDENTIFIERS Canada ABSTRACT Intended for teacheLs and practitioners, this film and video guide contains 235 entries pertaining to the administration of justice, culture and lifestyle, am: education and services in northern Canada, it is divided into eight sections: Native lifestyle (97 items); economic development (28), rights and self-government (20); education and training (14); criminal justice system (26); family services (19); youth and children (10); and alcohol and drug abuse/suicide (21). Each entry includes: title, responsible person or organization, name and address of distributor, date (1960-1984), format (16mm film, videotape, slide-tape, etc.), presence of accompanying support materials, length, sound and color information, language (predominantly English, some also French and Inuit), rental/purchase fees and preview availability, suggested use, and a brief description. -

A SALUTE to the NATIONAL FILM BOARD of CANADA Includes Sixteen Films Made Between

he Museum of Modern Art 1^ 111 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart Mo, 38 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Tuesday, April 25, 1967 On the occasion of The Canadian Centennial Week in New York, the Department of Film of The Museum of Modem Art will present A SALUTE TO THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA. Sixteen films produced by the National Film Board will be shown daily at the Museum from May U through May V->, except on Wednesdays. The program will be inaugu rated with a special screening for an invited audience on the evening of May 3j pre sented by The Consul General of Canada and The Canada Week Committee in association with the Museum. The National Film Board of Canada was established in 1939, with John Grierson, director of the British General Post Office film unit and leading documentary film producer, as Canada's first Government Film Commissioner, Its purpose is-to Jjiitdate and promote the production and distribution of films in the-uational int^rest^ \i\ par« ticular, films designed to interpret Canada to -Canadians and to other nations. Uniquely, each of its productions is available for showing in Canada as well as . abroad* Experimentation in all aspects of film-making has been actively continued and encouraged by the National Film Board. Funds are set aside for experiments, and all filmmakers are encouraged to attempt new techniques. Today the National Film Board of Canada produces more than 100 motion pictures each year with every film made in both English and French versions. -

Ing Lonely Boy

If the word documentary is synonymous with Canada, and the NFB is synonymous with Canadian documentary, it is impossible to consider the NFB, and particularly its fabled Unit B team, without one of its core members, Wolf Koenig. An integral part of the "dream team," he worked with, among others, Colin Low, Roman Kroitor, Terence Macartney-Filgate and unit head Tom Daly, as part of the NFB's most prolific and innovative ensemble. Koenig began his career as a splicer before moving on to animator, cameraman, director and producer, responsible for much of the output of the renowned Candid Eye series produced for CBC-TV between 1958 and 1961. Among Unit B's greatest achievements is Lonely Boy (1962), which bril- liantly captured the phenomenon of megastar mania before anyone else, and con- tinues to be screened worldwide. I had the opportunity to "speak" to Wolf Koenig in his first Internet interview, a fitting format for a self-professed tinkerer who made a career out of embracing the latest technologies. He reflects on his days as part of Unit B, what the term documentary means to him and the process of mak- ing Lonely Boy. What was your background before joining the NFB? One day, in early May 1948, my father got a call from a neighbour down the road — Mr. Merritt, the local agricultur- In 1937, my family fled Nazi Germany and came to Canada, al representative for the federal department of agriculture — just in the nick of time. After a couple of years of wonder- who asked if "the boy" could come over with the tractor to ing what he should do, my father decided that we should try out a new tree—planting machine. -

The Film Imagine an Angel Who Memorized All the Sights and Sounds of a City

The film Imagine an angel who memorized all the sights and sounds of a city. Imagine them coming to life: busy streets full of people and vehicles, activity at the port, children playing in yards and lanes, lovers kissing in leafy parks. Then recall the musical accompaniment of the past: Charles Trenet, Raymond Lévesque, Dominique Michel, Paul Anka, Willie Lamothe. Groove to an Oscar Peterson boogie. Dream to the Symphony of Psalms by Stravinsky. That city is Montreal. That angel guarding the sights and sounds is the National Film Board of Canada. The combined result is The Memories of Angels, Luc Bourdon’s virtuoso assembly of clips from 120 NFB films of the ’50s and ’60s. The Memories of Angels will charm audiences of all ages. It’s a journey in time, a visit to the varied corners of Montreal, a tribute to the vitality of the city and a wonderful cinematic adventure. It recalls Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire in which angels flew over and watched the citizens of Berlin. It has the same sense of ubiquity, the same flexibility, the sense of dreamlike freedom allowing us to fly from Place Ville- Marie under construction to the workers in a textile factory or firemen at work. Underpinning the film is Stravinsky’s music, representing love, hope and faith. A firefighter has died. The funeral procession makes its way up St. Laurent Boulevard. The Laudate Dominum of the 20th century’s greatest composer pays tribute to him. Without commentary, didacticism or ostentation, the film is a history lesson of the last century: the red light district, the eloquent Jean Drapeau, the young Queen Elizabeth greeting the crowd and Tex Lecor shouting “Aux armes Québécois !” Here are kids dreaming of hockey glory, here’s the Jacques-Cartier market bursting with fresh produce, and the department stores downtown thronged with Christmas shoppers. -

NORMAN MCLAREN RETROSPECTIVE at Moma

The Museum of Modern Art 50th Anniversary NO. 7 no FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NORMAN MCLAREN RETROSPECTIVE AT MoMA As part of NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA: A RETROSPECTIVE, Norman McLaren, master animator and founder of the Board's an imation unit in 1941, will be honored with a retrospective of virtually all the films he made at NFBC. Part One of MoMA's NFBC Retrospective, ANIMATION, runs from January 22 through February 16, and presents a survey of 150 animated films. Five programs of the extraordinary and influential work of Norman McLaren will be presented from February 12 through 16. "Animation came to the National Film Board of Canada in 1941 with the person of Norman McLaren. In 1943, after having recruited George Dunning, Jim MacKay and Grant Munro, it was McLaren who was put in charge of the first animation workshop. The earliest films were craftsmanlike, having a more utilitarian than aesthetic character. After the war the time of the artist came about. The spirit and goals of the animation unit changed; the styles and techniques became more and more refined leading to today's sophisticated animation." —Louise Beaudet, Head of Animation Department, Cinematheque quebecoise, Montreal "Norman McLaren (Stirling, Scotland, 1914) completed his first abstract films in 1933 while a student at the Glasgow School of Art, Here he attracted the attention of John Grierson, who invited the young man upon graduation to make promotional films for the General Post Office in London. McLaren worked for the GPO from 1936 until 1939 when, at the onset of war, he moved to New York. -

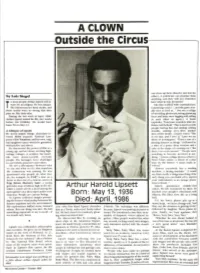

Outside the Circus

A CLOWN .-----Outside the Circus------. ous close-up faces dissolve one into the by Lois Siegel other). A politician can promise them anything, and they will not remember o most people Arthur Lipsett will al- , later what he has promised." ways be an enigma. He was unique. The film is fllied with contradictions: THis idiosyncracies bred myths,. and (stuttering voice) " ... and the game is re these myths were so strong that they. ally nice to look at..." (we see a collage pass on, like fairy-tales. of wrestling photos picturing grimacing During the last week of April, 1986, faces and hefty men tugging and pulling Arthur Lipsett ended his life, two weeks at each other in agony). A bomb before his birthday. He would have explodes: "Everyone wonders what the been 50 on May 13. future will behold." This is intercut with people having fun and smiling: smiling A Glimpse of Lipsett mouths, smiling eyes ... then another He loved simple things: chocolate-co shot of the bomb... (man's voice) "This vered M&M peanuts; National Lam is my line, and I love it." Later we see poon's film Vacation, and his own, orig shots of newspapers: "There's sort of a inal spaghetti sauce which he garnished passing interest in things." (followed by with pickles and olives. c: a shot of a pastry-shop window and a He discovered the power of mm at a ~ cake in the shape of a smiling cat). "But young age and set about creating high {l there's no real concern." "People seem () voltage collages. -

Unbridgeable Barriers: the Holocaust in Canadian Cinema by Jeremy

Unbridgeable Barriers: The Holocaust in Canadian Cinema by Jeremy Maron A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Mediations Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2011, Jeremy Maron Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de Pedition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre riterence ISBN: 978-0-494-83210-3 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-83210-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Rue Atones Torill Kove Reinvents Her Grandmother's Life in Oslo During World War II, Combining Anecdotes, History, Fantasy and Humour

rue orve An irreverent collection of funny films about serious questions. and ^* % My Grandmother Ironed the King's Shirts makes its b and quirky video debut alongside award-winning NFB classics My Grandmother Ironed the King's Shirts rue Atones Torill Kove reinvents her grandmother's life in Oslo during World War II, combining anecdotes, history, fantasy and humour. (10 min, 35 sec) Director: Torill Kove Producers: Marcy Page (NFB), Lars Tommerbakke (Studio Magica, Norway) The Family that Dwelt Apart A tall tale by E.B. White v about a family living happily on a small island until word gets out that they are in distress. (7 min, 55 sec) Director: Yvon Mallette Producer: Wolf Koenig The House that Jack Built Pokes fun at ambition, the rat race and consumerism. (8 min, 2 sec) Director: Ron Tunis Producers: Wolf Koenig, Jim Mackay Arkelope A seriously funny look at nature documentaries. (5 min, 17 sec) Director: Roslyn Schwartz Producer: Marcy Page Traditional folklore takes a wry turn in Spinnolio, the tale of a carved wooden puppet that lacks mobility and human consciousness. (9 min, 51 sec) Director: John Weldon Producer: Wolf Koenig Total running time: 41 min 16 sec TO ORDER NFB VIDEOS, CALL TODAY! 1-800-267-7710 (Canada) 1-800-542-2164 (USA) www.nfb.ca © 1999 A licence is required for any reproduction, television broadcast, sale, rental or public screening. Only educational institutions or non-profit organizations who have obtained this video directly from the NFB have the right to show this video free of charge to the public. -

Sounds Like Canada Longfield, Michael Cineaction; 2009; 77; CBCA Complete Pg- 9

Sounds Like Canada Longfield, Michael Cineaction; 2009; 77; CBCA Complete Pg- 9 Sounds Like Canada A REEXAMINATION OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF CANADIAN CINEMA-VERITE MICHAEL LONGFIELD It is well known that within the kingdom of nonfiction film, the For example, in Canada, the National Film Board's federal order of "direct documentary", regardless of genus (cinema- mandate and funding opportunities, guided by producer Tom verite, Direct Cinema, Free Cinema, Candid Eye), did not emerge Daly's benevolent leadership at Unit B, created a unique kind of fully formed from the brow of any of its progenitors no matter documentary laboratory. Daly, who had apprenticed with John how organic its evolution may appear in hindsight. It developed Grierson and Stuart Legg at the Board during the war years, was through a confluence of factors (technical, aesthetic, authorial) a gifted film editor, and his years at the helm of Unit B offered marshaled by filmmakers in France, the U.S., England, and those more ambitious or visionary filmmakers a strong sense of Canada. Throughout the mid 50s and early 60s we see an structure. Beyond the cinematic texts themselves, trouble-shoot- exchange of ideas, equipment, and even personnel between ing new technical and aesthetic challenges offered unparalleled these camps. Technology alone did not enable these films, and training to the filmmakers working under Daly, and those skills there is evident a large variation in terms of how the technolo- would be exported abroad. French director Jean Rouch perhaps gy was deployed. not-so-famously credited his partnership with NFB director-cam- Pour la suite du monde (1963) •• «s<5r *.•• • OSK Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

George Stoney Interviewed by Emren Meroglu & Gary Porter Edited By

George Stoney Interviewed by Emren Meroglu & Gary Porter Edited by Michael Baker VTR St-Jacques (réal. Bonnie Sherr Klein ; prod. George C. Stoney, 1969) © Office National du Film / National Film Board George Stoney arrived at the National Film Board of Canada in 1968 to oversee the Challenge for Change programme as its executive producer. U.S. born with a background in journalism, educational film and documentary, Stoney arrived with a strong commitment to socially engaged filmmaking. His impact on the ethical dimensions of the NFB’s programme was immediate and proved long-lasting; his interest in film and video as tools for organizing communities continues, as does his influence on new generations of documentary filmmakers. The Library of Congress added All My Babies, his landmark 1953 film about African American midwifery in the American south, to the National Film Registry in 2002. Roots in the National Film Board Bonnie Klein was the person who suggested to the NFB that they might consider me to head the Challenge for Change programme [following John Kemeny’s departure], but I had had a long Emren Meroglu, Gary Porter and Michael Baker - George Stoney 1 Nouvelles «vues» sur le cinéma québécois, no 5, Printemps 2006 www.cinema-quebecois.net association with the NFB before that. Nicholas Reid, an American who had worked at the NFB for four years, brought me into film in 1946. He had been greatly influenced by Grierson. I said, “I don’t know anything about film, I’m a journalist.” He said, “Fine, we will bring people down from the NFB to work with you.” So we had a number of people come down and join us in Athens, Georgia and we used to see those early NFB films — so that was, in effect, my film school. -

Ontario Producer Constraints and Opportunities James Warrack a Thesis Submitted to the Facu

BUSINESS MODELS FOR FILM PRODUCTION: ONTARIO PRODUCER CONSTRAINTS AND OPPORTUNITIES JAMES WARRACK A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS GRADUATE PROGAM IN INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES YORK UNIVERSITY, TORONTO, ONTARIO January 2012 © James Warrack, 2012 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-90026-0 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-90026-0 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation.