Norman Mclaren: Between the Frames

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATIONAL FILM BOARD of CANADA FEATURED at Moma

The Museum off Modern Art 50th Anniversary NO. 16 ID FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 3, 1981 DOCUMENTARY FILMS FROM THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA FEATURED AT MoMA NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA: A RETROSPECTIVE is a three-part tribute presented by The Museum of Modern Art in recog nition of NFBC's 41 years Of exceptional filmmaking. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY FILMS, running from March 26 through May 12 in the Museum's Roy and Niuta Titus Auditorium, will trace the develop ment of the documentary form at NFBC, and will be highlighted by a selection of some of the finest films directed by Donald Brittain, whose work has won wide acclaim and numerous awards. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY will get off to an auspicious start with twelve of Donald Brittain's powerful and unconventional portraits of exceptional individuals. Best known in this country for "Volcano: An Inquiry Into The Life and Death of Malcolm Lowry" (1976), Brittain brings his personal stamp of creative interpretation to such subjects as America's love affair with the automobile in "Henry Ford's America" (1976) ; the flamboyant Lord Thompson of Fleet Street (the newspaper baron who just sold the cornerstone of his empire, The London Times) in "Never A Backward Step" (1966); Norman Bethune, the Canadian poet/ doctor/revolutionary who became a great hero in China when he marched with Mao ("Bethune" 1964); and the phenomenal media hysteria sur rounding the famous quintuplets in "The Diorme Years" (1979) . "Memo randum" (1965) accompanies a Jewish glazier from Tcronto when he takes his son back to the concentration camp where he was interned, an emotion al and historical pilgrimage of strong impact and sensitivity. -

The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema to Access Digital Resources Including: Blog Posts Videos Online Appendices

Robert Phillip Kolker The Altering Eye Contemporary International Cinema To access digital resources including: blog posts videos online appendices and to purchase copies of this book in: hardback paperback ebook editions Go to: https://www.openbookpublishers.com/product/8 Open Book Publishers is a non-profit independent initiative. We rely on sales and donations to continue publishing high-quality academic works. Robert Kolker is Emeritus Professor of English at the University of Maryland and Lecturer in Media Studies at the University of Virginia. His works include A Cinema of Loneliness: Penn, Stone, Kubrick, Scorsese, Spielberg Altman; Bernardo Bertolucci; Wim Wenders (with Peter Beicken); Film, Form and Culture; Media Studies: An Introduction; editor of Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho: A Casebook; Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey: New Essays and The Oxford Handbook of Film and Media Studies. http://www.virginia.edu/mediastudies/people/adjunct.html Robert Phillip Kolker THE ALTERING EYE Contemporary International Cinema Revised edition with a new preface and an updated bibliography Cambridge 2009 Published by 40 Devonshire Road, Cambridge, CB1 2BL, United Kingdom http://www.openbookpublishers.com First edition published in 1983 by Oxford University Press. © 2009 Robert Phillip Kolker Some rights are reserved. This book is made available under the Cre- ative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial 2.0 UK: England & Wales Licence. This licence allows for copying any part of the work for personal and non-commercial use, providing author -

The Grierson Effect

Copyright material – 9781844575398 Contents Acknowledgments . vii Notes on Contributors . ix Introduction . 1 Zoë Druick and Deane Williams 1 John Grierson and the United States . 13 Stephen Charbonneau 2 John Grierson and Russian Cinema: An Uneasy Dialogue . 29 Julia Vassilieva 3 To Play The Part That Was in Fact His/Her Own . 43 Brian Winston 4 Translating Grierson: Japan . 59 Abé Markus Nornes 5 A Social Poetics of Documentary: Grierson and the Scandinavian Documentary Tradition . 79 Ib Bondebjerg 6 The Griersonian Influence and Its Challenges: Malaya, Singapore, Hong Kong (1939–73) . 93 Ian Aitken 7 Grierson in Canada . 105 Zoë Druick 8 Imperial Relations with Polynesian Romantics: The John Grierson Effect in New Zealand . 121 Simon Sigley 9 The Grierson Cinema: Australia . 139 Deane Williams 10 John Grierson in India: The Films Division under the Influence? . 153 Camille Deprez Copyright material – 9781844575398 11 Grierson in Ireland . 169 Jerry White 12 White Fathers Hear Dark Voices? John Grierson and British Colonial Africa at the End of Empire . 187 Martin Stollery 13 Grierson, Afrikaner Nationalism and South Africa . 209 Keyan G. Tomaselli 14 Grierson and Latin America: Encounters, Dialogues and Legacies . 223 Mariano Mestman and María Luisa Ortega Select Bibliography . 239 Appendix: John Grierson Biographical Timeline . 245 Index . 249 Copyright material – 9781844575398 Introduction Zoë Druick and Deane Williams Documentary is cheap: it is, on all considerations of public accountancy, safe. If it fails for the theatres it may, by manipulation, be accommodated non-theatrically in one of half a dozen ways. Moreover, by reason of its cheapness, it permits a maximum amount of production and a maximum amount of directorial training against the future, on a limited sum. -

Documentary America: Exploring Popular Culture

Review Essay Documentary America: Exploring Popular Culture Sam Girgus DOCUMENTING OURSELVES: Film, Video, and Culture. By Sharon R. Sherman. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. 1998. HOLLYWOOD'S INDIAN: The Portrayal of the Native American in Film. Edited by Peter C. Rollins and John E. O'Connor. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. 1998. DISASTER AND MEMORY: Celebrity Culture and the Crisis of Hollywood Cinema. By Wheeler Winston Dixon. New York: Columbia University Press. 1999. Documentary today influences and structures the way we think about and envision current events and history. The proliferation of documentary, of course, stems in part from its importance to television as specials, docudramas, and public broadcasting endeavors such as Ken Burns' The Civil War (1989). Also, docu mentary films such as Michael Moore's Roger andMe (1989) achieve critical and commercial success. Yet, while documentary for information and entertainment grows in popularity and authority, its relation to film as an art and to culture studies remains generally misunderstood and neglected. Thus, documentary requires further study to explain its place in our culture. 0026-3079/99/4003-147$2.00/0 American Studies, 40:3 (Fall 1999): 147-155 147 148 Sam Girgus Besides the cost efficiency of documentary as compared to commercial films, the power and popularity of documentary also derive from the conventional belief in its special relationship to reality. In her important new book, Document ing Ourselves: Film, Video, and Culture, Sharon R. Sherman uses a familiar but descriptive label to identify this idea of documentary realism as a "'slice of life'" (10). For many, documentary provides a visual and audial piece of actual experience, rendering that experience with an immediacy to reality that obviates the mediation of written texts and artistic forms. -

Northern Conference Film and Video Guide on Native and Northern Justice Issues

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 287 653 RC 016 466 TITLE Northern Conference Film and Video Guide on Native and Northern Justice Issues. INSTITUTION Simon Fraser Univ., Burnaby (British Columbia). REPORT NO ISBN-0-86491-051-7 PUB DATE 85 NOTE 247p.; Prepared by the Northern Conference Resource Centre. AVAILABLE FROM Northern Conference Film Guide, Continuing Studies, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada V5A 1S6 ($25.00 Canadian, $18.00 U.S. Currency). PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Adolescent Development; *American Indians; *Canada Natives; Children; Civil Rights; Community Services; Correctional Rehabilitation; Cultural Differences; *Cultural Education; *Delinquency; Drug Abuse; Economic Development; Eskimo Aleut Languages; Family Life; Family Programs; *Films; French; Government Role; Juvenile Courts; Legal Aid; Minority Groups; Slides; Social Problems; Suicide; Tribal Sovereignty; Tribes; Videotape Recordings; Young Adults; Youth; *Youth Problems; Youth Programs IDENTIFIERS Canada ABSTRACT Intended for teacheLs and practitioners, this film and video guide contains 235 entries pertaining to the administration of justice, culture and lifestyle, am: education and services in northern Canada, it is divided into eight sections: Native lifestyle (97 items); economic development (28), rights and self-government (20); education and training (14); criminal justice system (26); family services (19); youth and children (10); and alcohol and drug abuse/suicide (21). Each entry includes: title, responsible person or organization, name and address of distributor, date (1960-1984), format (16mm film, videotape, slide-tape, etc.), presence of accompanying support materials, length, sound and color information, language (predominantly English, some also French and Inuit), rental/purchase fees and preview availability, suggested use, and a brief description. -

A New History of British Documentary This Page Intentionally Left Blank a New History of British Documentary

A New History of British Documentary This page intentionally left blank A New History of British Documentary James Chapman University of Leicester, UK © James Chapman 2015 Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2015 978-0-230-39286-1 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The author has asserted his right to be identified as the author of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2015 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. Palgrave Macmillan in the US is a division of St Martin’s Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010. Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world. Palgrave® and Macmillan® are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries. ISBN 978-1-349-35209-8 ISBN 978-0-230-39287-8 (eBook) DOI 10.1057/9780230392878 This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. -

From Real Time to Reel Time: the Films of John Schlesinger

From Real Time to Reel Time: The Films of John Schlesinger A study of the change from objective realism to subjective reality in British cinema in the 1960s By Desmond Michael Fleming Submitted in total fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2011 School of Culture and Communication Faculty of Arts The University of Melbourne Produced on Archival Quality Paper Declaration This is to certify that: (i) the thesis comprises only my original work towards the PhD, (ii) due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used, (iii) the thesis is fewer than 100,000 words in length, exclusive of tables, maps, bibliographies and appendices. Abstract The 1960s was a period of change for the British cinema, as it was for so much else. The six feature films directed by John Schlesinger in that decade stand as an exemplar of what those changes were. They also demonstrate a fundamental change in the narrative form used by mainstream cinema. Through a close analysis of these films, A Kind of Loving, Billy Liar, Darling, Far From the Madding Crowd, Midnight Cowboy and Sunday Bloody Sunday, this thesis examines the changes as they took hold in mainstream cinema. In effect, the thesis establishes that the principal mode of narrative moved from one based on objective realism in the tradition of the documentary movement to one which took a subjective mode of narrative wherein the image on the screen, and the sounds attached, were not necessarily a record of the external world. The world of memory, the subjective world of the mind, became an integral part of the narrative. -

SOUL of the DOCUMENTARY , Ilona Hongisto Stirs Current Thinking About

Ilona Hongisto Documentary does not simply document what is; it presses reality to reveal what is to come. This thrillingly original and well-argued book brings a shot of energy to studies of documentary cinema, film theory, and the philos ophy of Gilles Deleuze. Ilona Hongisto shows that documentary cinema is an active space of becoming, whose power lies not in indexicality but in capture, the OF THE selection of certain aspects of the real to actualize. Her anal ysis of the aesthe- SOUL tics of the documentary frame, which captures and expresses according to the distinct operations of imagination, fabulation, and affection, will inspire scholars and filmmakers alike. DOCUMENTARY Laura U. Marks, School for the Contemporary Arts, Simon Fraser University FRAMING, EXPRESSION, ETHICS SOUL In SOUL OF THE DOCUMENTARY , Ilona Hongisto stirs current thinking about documentary cinema by suggesting that the work of documentary films is not reducible to representing what already exists. By close-reading a diverse OF THE OF THE body of films – from The Last Bolshevik to Grey Gardens – Hongisto shows how documentary cinema intervenes in the real by framing it and creatively contributes to its perpetual unfolding. The emphasis on framing brings new urgency to the documentary tradition and its objectives, and provokes significant novel possibilities for thinking about the documentary’s ethical DOCUMENTARY and political potentials in the contemporary world. Ilona Hongisto is an Academy of Finland Postdoctoral Fellow in the department of Media Studies at The University of Turku, Finland, and an Honorary Fellow at the Victorian College of the Arts, The University of Melbourne, Australia. -

A SALUTE to the NATIONAL FILM BOARD of CANADA Includes Sixteen Films Made Between

he Museum of Modern Art 1^ 111 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart Mo, 38 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Tuesday, April 25, 1967 On the occasion of The Canadian Centennial Week in New York, the Department of Film of The Museum of Modem Art will present A SALUTE TO THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA. Sixteen films produced by the National Film Board will be shown daily at the Museum from May U through May V->, except on Wednesdays. The program will be inaugu rated with a special screening for an invited audience on the evening of May 3j pre sented by The Consul General of Canada and The Canada Week Committee in association with the Museum. The National Film Board of Canada was established in 1939, with John Grierson, director of the British General Post Office film unit and leading documentary film producer, as Canada's first Government Film Commissioner, Its purpose is-to Jjiitdate and promote the production and distribution of films in the-uational int^rest^ \i\ par« ticular, films designed to interpret Canada to -Canadians and to other nations. Uniquely, each of its productions is available for showing in Canada as well as . abroad* Experimentation in all aspects of film-making has been actively continued and encouraged by the National Film Board. Funds are set aside for experiments, and all filmmakers are encouraged to attempt new techniques. Today the National Film Board of Canada produces more than 100 motion pictures each year with every film made in both English and French versions. -

Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from Manchesterhive.Com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM Via Free Access HALF the BATTLE

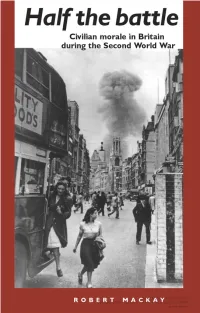

Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access HALF THE BATTLE Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 1 16/09/02, 09:21 Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 2 16/09/02, 09:21 HALF THE BATTLE Civilian morale in Britain during the Second World War ROBERT MACKAY Manchester University Press Manchester and New York distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave Robert Mackay - 9781526137425 Downloaded from manchesterhive.com at 09/24/2021 07:30:30PM via free access prelim.p65 3 16/09/02, 09:21 Copyright © Robert Mackay 2002 The right of Robert Mackay to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. Published by Manchester University Press Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9NR, UK and Room 400, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk Distributed exclusively in the USA by Palgrave, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010, USA Distributed exclusively in Canada by UBC Press, University of British Columbia, 2029 West Mall, Vancouver, BC, Canada V6T 1Z2 British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for ISBN 0 7190 5893 7 hardback 0 7190 5894 5 paperback First published 2002 10 09 08 07 06 05 04 03 02 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Typeset by Freelance Publishing Services, Brinscall, Lancs. -

Ing Lonely Boy

If the word documentary is synonymous with Canada, and the NFB is synonymous with Canadian documentary, it is impossible to consider the NFB, and particularly its fabled Unit B team, without one of its core members, Wolf Koenig. An integral part of the "dream team," he worked with, among others, Colin Low, Roman Kroitor, Terence Macartney-Filgate and unit head Tom Daly, as part of the NFB's most prolific and innovative ensemble. Koenig began his career as a splicer before moving on to animator, cameraman, director and producer, responsible for much of the output of the renowned Candid Eye series produced for CBC-TV between 1958 and 1961. Among Unit B's greatest achievements is Lonely Boy (1962), which bril- liantly captured the phenomenon of megastar mania before anyone else, and con- tinues to be screened worldwide. I had the opportunity to "speak" to Wolf Koenig in his first Internet interview, a fitting format for a self-professed tinkerer who made a career out of embracing the latest technologies. He reflects on his days as part of Unit B, what the term documentary means to him and the process of mak- ing Lonely Boy. What was your background before joining the NFB? One day, in early May 1948, my father got a call from a neighbour down the road — Mr. Merritt, the local agricultur- In 1937, my family fled Nazi Germany and came to Canada, al representative for the federal department of agriculture — just in the nick of time. After a couple of years of wonder- who asked if "the boy" could come over with the tractor to ing what he should do, my father decided that we should try out a new tree—planting machine. -

Transnationalizing Radio Research

Golo Föllmer, Alexander Badenoch (eds.) Transnationalizing Radio Research Media Studies | Volume 42 Golo Föllmer, Alexander Badenoch (eds.) Transnationalizing Radio Research New Approaches to an Old Medium . Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No- Derivatives 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non-commer- cial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work and for commer- cial use, further permission is required and can be obtained by contacting rights@ transcript-verlag.de Creative Commons license terms for re-use do not apply to any content (such as graphs, figures, photos, excerpts, etc.) not original to the Open Access publication and further permission may be required from the rights holder. The obligation to research and clear permission lies solely with the party re-using the material. © 2018 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld Cover layout: Maria Arndt, Bielefeld Typeset: Anja Richter Printed by Majuskel Medienproduktion GmbH, Wetzlar Print-ISBN 978-3-8376-3913-1 PDF-ISBN 978-3-8394-3913-5 Contents INTRODUCTION Transnationalizing Radio Research: New Encounters with an Old Medium Alexander Badenoch