Ing Lonely Boy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NATIONAL FILM BOARD of CANADA FEATURED at Moma

The Museum off Modern Art 50th Anniversary NO. 16 ID FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 3, 1981 DOCUMENTARY FILMS FROM THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA FEATURED AT MoMA NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA: A RETROSPECTIVE is a three-part tribute presented by The Museum of Modern Art in recog nition of NFBC's 41 years Of exceptional filmmaking. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY FILMS, running from March 26 through May 12 in the Museum's Roy and Niuta Titus Auditorium, will trace the develop ment of the documentary form at NFBC, and will be highlighted by a selection of some of the finest films directed by Donald Brittain, whose work has won wide acclaim and numerous awards. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY will get off to an auspicious start with twelve of Donald Brittain's powerful and unconventional portraits of exceptional individuals. Best known in this country for "Volcano: An Inquiry Into The Life and Death of Malcolm Lowry" (1976), Brittain brings his personal stamp of creative interpretation to such subjects as America's love affair with the automobile in "Henry Ford's America" (1976) ; the flamboyant Lord Thompson of Fleet Street (the newspaper baron who just sold the cornerstone of his empire, The London Times) in "Never A Backward Step" (1966); Norman Bethune, the Canadian poet/ doctor/revolutionary who became a great hero in China when he marched with Mao ("Bethune" 1964); and the phenomenal media hysteria sur rounding the famous quintuplets in "The Diorme Years" (1979) . "Memo randum" (1965) accompanies a Jewish glazier from Tcronto when he takes his son back to the concentration camp where he was interned, an emotion al and historical pilgrimage of strong impact and sensitivity. -

Graeme Ferguson

Ontario Place - home of IMAX Ferguson: It's a film about what it's hke film in Cinesphere? to join the circus, to be a Ferguson: Not for the pubhc. We'll Graeme performer in the circus. The film is pro probably be doing our pre duced and directed by my partner views there. It's the only existing theatre Roman Kroitor, and will probably be Ferguson called "This Way to the Big Show." where we can look at an IMAX film. Ques: Will IMAX be part of all world Ques: Did he use actors in the fUm? — by Shelby M. Gregory and Phyllis Expos to come? Wilson. Ferguson: No, he used only circus per Ferguson: There is an Expo taking place sonnel. Roman took the cam Graeme Ferguson is the Director- in Spokane in 1974, and the era right into the circus, and filmed Cameraman-Producer of "North of United States PaviUon will feature an during actual performances. It was very Superior". He is also president of Multi- IMAX theatre. Screen Corporation Limited, located in difficult because they could only get Gait-Cambridge, Ontario (developers of about two or three shots in any one Ques: Are they paying for the produc IMAX). performance. tion of a film? Ques: Was this filmed with the standard Ferguson: Yes, Paramount Pictures is Ques: What have you been doing since IMAX camera? producing, and Roman and I North of Superior? are involved. Ferguson: Yes, John Spotton was the Ferguson: We're just finishing a film for cameraman. Eldon Rathburn, Ques: Is it a feature film? Ringhng Brothers and Bar- who did the music for Labyrinth, is num and Bailey. -

Northern Conference Film and Video Guide on Native and Northern Justice Issues

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 287 653 RC 016 466 TITLE Northern Conference Film and Video Guide on Native and Northern Justice Issues. INSTITUTION Simon Fraser Univ., Burnaby (British Columbia). REPORT NO ISBN-0-86491-051-7 PUB DATE 85 NOTE 247p.; Prepared by the Northern Conference Resource Centre. AVAILABLE FROM Northern Conference Film Guide, Continuing Studies, Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, British Columbia, Canada V5A 1S6 ($25.00 Canadian, $18.00 U.S. Currency). PUB TYPE Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Adolescent Development; *American Indians; *Canada Natives; Children; Civil Rights; Community Services; Correctional Rehabilitation; Cultural Differences; *Cultural Education; *Delinquency; Drug Abuse; Economic Development; Eskimo Aleut Languages; Family Life; Family Programs; *Films; French; Government Role; Juvenile Courts; Legal Aid; Minority Groups; Slides; Social Problems; Suicide; Tribal Sovereignty; Tribes; Videotape Recordings; Young Adults; Youth; *Youth Problems; Youth Programs IDENTIFIERS Canada ABSTRACT Intended for teacheLs and practitioners, this film and video guide contains 235 entries pertaining to the administration of justice, culture and lifestyle, am: education and services in northern Canada, it is divided into eight sections: Native lifestyle (97 items); economic development (28), rights and self-government (20); education and training (14); criminal justice system (26); family services (19); youth and children (10); and alcohol and drug abuse/suicide (21). Each entry includes: title, responsible person or organization, name and address of distributor, date (1960-1984), format (16mm film, videotape, slide-tape, etc.), presence of accompanying support materials, length, sound and color information, language (predominantly English, some also French and Inuit), rental/purchase fees and preview availability, suggested use, and a brief description. -

Estta1050036 04/20/2020 in the United States Patent And

Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Electronic Filing System. http://estta.uspto.gov ESTTA Tracking number: ESTTA1050036 Filing date: 04/20/2020 IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD Proceeding 91254173 Party Plaintiff IMAX Corporation Correspondence CHRISTOPHER P BUSSERT Address KILPATRICK TOWNSEND & STOCKTON LLP 1100 PEACHTREE STREET, SUITE 2800 ATLANTA, GA 30309 UNITED STATES [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] 404-815-6500 Submission Motion to Amend Pleading/Amended Pleading Filer's Name Christopher P. Bussert Filer's email [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Signature /Christopher P. Bussert/ Date 04/20/2020 Attachments 2020.04.20 Amended Notice of Opposition for Shenzhen Bao_an PuRuiCai Electronic Firm Limited.pdf(252165 bytes ) IN THE UNITED STATES PATENT AND TRADEMARK OFFICE BEFORE THE TRADEMARK TRIAL AND APPEAL BOARD In the matter of Application Serial No. 88/622,245; IMAXCAN; Published in the Official Gazette of January 21, 2020 IMAX CORPORATION, ) ) Opposer, ) ) v. ) Opposition No. 91254173 ) SHENZHEN BAO’AN PURUICAI ) ELECTRONIC FIRM LIMITED, ) ) Applicant. ) AMENDED NOTICE OF OPPOSITION Opposer IMAX Corporation (“Opposer”), a Canadian corporation whose business address is 2525 Speakman Drive, Sheridan Science and Technology Park, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada L5K 1B1, believes that it will be damaged by registration of the IMAXCAN mark as currently shown in Application Serial No. 88/622,245 and hereby submits this Amended Notice of Opposition pursuant to 37 C.F.R. §2.107(a) and Fed. R. Civ. P. 15, by which Opposer opposes the same pursuant to the provisions of 15 U.S.C. -

1 Citizenship and Participatory Video Marit Kathryn Corneil

1 Citizenship and Participatory Video Marit Kathryn Corneil In Screen Media Arts: An Introduction to Concepts and Practices (Cohen, Salazar, and Barkat, 2008) participatory video is defined broadly as “a tool for individual, group and community development” and as “an iter- ative process, whereby community members use video to document in- novations and ideas, or to focus on issues that affect their environment” (pp. 348–349). Most accounts of the origins of participatory video refer to the Fogo Process or the Fogo Method as the original inspiration for these techniques. The Fogo Method originated in the Fogo Island Com- munication Experiment, one of the initial projects under the umbrella of the experimental program in ethical documentary at the National Film Board of Canada, the Challenge for Change/Société Nouvelle program (CFC/SN). CFC/SN ran from 1967 to 1980, producing more than 200 films and videos, and, since 2000, has inspired renewed interest in academic re- search circles and among media practitioners after more than 30 years of considerable neglect in the archive. It was thought for many years that the films produced under the banner of CFC/SN were too local and too aesthetically uninteresting to merit attention. Only recently have some of these films been recuperated for documentary history; they have been shown to represent revolutionary thinking about documentary politics, ethics, and aesthetics (Waugh, Baker, and Winton, 2010). CFC/SN was one of a number of programs inspired by the civil rights movements of the 1960s with a mission to tackle the sources of poverty and exclusion; to “give voice” to marginalized segments of society; to facilitate communi- cation; and to keep minorities from becoming the victims and stereotypes 19 20 / Chapter 1 of media and government. -

Canadian Innovations

CanadianStories of Canadian Innovations Innovation McIntosh Red Apple The McIntosh Red is a world-famous apple that was discovered in Ontario in 1811. John McIntosh, a settler from New York, found apple-tree seedlings as he cleared brush on his Dundela farm, near Morrisburg on the St Lawrence River. McIntosh transplanted the trees and one bore delicious fruit: a deep-red apple with tart flavour and tender white flesh. Over the decades, the McIntosh family propagated their unique apple by grafting scions, or cuttings, to other fruit trees in their orchard. Allan McIntosh, John’s son, continued this work. He established a McIntosh Red nursery in 1870 and sold trees to other orchardists. By the early 1900s, the McIntosh Red was popular across North America. Apple breeders, such as W. T. Macoun at the Central Experimental Farm in Ottawa, used the hardy McIntosh Red to create new varieties including Lobo, Cortland, Empire, and Spartan. Farm botanist and artist Faith Fyles recorded some of this breeding work in beautiful watercolours. And while new apple varieties like Gala and Honeycrisp have challenged the McIntosh Red’s supremacy, the McIntosh apple remains a favourite both for cooking and for eating fresh. Notably, the McIntosh Red inspired the name of the Macintosh computer. Jef Raskin, an Apple engineer, called the McIntosh “my favourite kind of eatin’ apple.” Allan McIntosh Ottawa, February 1908 beside a “McIntosh Red” apple tree, Hawker Hurricane The Hawker Hurricane gained fame for its role in defeating the German air force during the Battle of Britain in 1940. Robust and rugged, the Hurricane was a single-seat monoplane launched in 1935. -

A SALUTE to the NATIONAL FILM BOARD of CANADA Includes Sixteen Films Made Between

he Museum of Modern Art 1^ 111 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart Mo, 38 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Tuesday, April 25, 1967 On the occasion of The Canadian Centennial Week in New York, the Department of Film of The Museum of Modem Art will present A SALUTE TO THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA. Sixteen films produced by the National Film Board will be shown daily at the Museum from May U through May V->, except on Wednesdays. The program will be inaugu rated with a special screening for an invited audience on the evening of May 3j pre sented by The Consul General of Canada and The Canada Week Committee in association with the Museum. The National Film Board of Canada was established in 1939, with John Grierson, director of the British General Post Office film unit and leading documentary film producer, as Canada's first Government Film Commissioner, Its purpose is-to Jjiitdate and promote the production and distribution of films in the-uational int^rest^ \i\ par« ticular, films designed to interpret Canada to -Canadians and to other nations. Uniquely, each of its productions is available for showing in Canada as well as . abroad* Experimentation in all aspects of film-making has been actively continued and encouraged by the National Film Board. Funds are set aside for experiments, and all filmmakers are encouraged to attempt new techniques. Today the National Film Board of Canada produces more than 100 motion pictures each year with every film made in both English and French versions. -

Cailen Pybus

Pybus 1 Introduction Beyond the entrance, passing under an enormous sculpture of a minotaur’s head, you walk down a long, straight, narrow corridor with walls of indistinguishable height disappearing into blackness. Despite the sense of crampt emptiness the corridor gives you, you are all the while comforted by the presence of dozens of other wonder-struck visitors. Your group distributes among four different floors where they remain for the rest of the excursion. Your group arrives at the first chamber and watches a huge film projected on both the floor and a wall in a way you’ve never seen before. The film finishes and you proceed behind the wall screen and through the narrow maze of the second chamber while formless ‘moving’ sounds and synchronized blinking lights reflect infinitely from mirrors all around you, and you find yourself in contemplation. Finally your group arrives at the third chamber, the last chamber, where you are once again confronted by a strange screen composed of five smaller screens arranged in a cross. You twist and turn your neck to see everything you can on the screens. You’re too close to see everything on the screens in a single gaze. You move and look and absorb every strange emotion unfold on the screen and around you until the film abruptly ends. You leave the pavilion. Emerging from darkness you see an elevated view of the St. Lawrence River and the remaining Expo grounds of Ile-Notre-Dame and Ile-Sainte-Helene in the distance. Such was the experience of the Labyrinth pavilion from the National Film Board of Canada at Expo ’671. -

The Film Imagine an Angel Who Memorized All the Sights and Sounds of a City

The film Imagine an angel who memorized all the sights and sounds of a city. Imagine them coming to life: busy streets full of people and vehicles, activity at the port, children playing in yards and lanes, lovers kissing in leafy parks. Then recall the musical accompaniment of the past: Charles Trenet, Raymond Lévesque, Dominique Michel, Paul Anka, Willie Lamothe. Groove to an Oscar Peterson boogie. Dream to the Symphony of Psalms by Stravinsky. That city is Montreal. That angel guarding the sights and sounds is the National Film Board of Canada. The combined result is The Memories of Angels, Luc Bourdon’s virtuoso assembly of clips from 120 NFB films of the ’50s and ’60s. The Memories of Angels will charm audiences of all ages. It’s a journey in time, a visit to the varied corners of Montreal, a tribute to the vitality of the city and a wonderful cinematic adventure. It recalls Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire in which angels flew over and watched the citizens of Berlin. It has the same sense of ubiquity, the same flexibility, the sense of dreamlike freedom allowing us to fly from Place Ville- Marie under construction to the workers in a textile factory or firemen at work. Underpinning the film is Stravinsky’s music, representing love, hope and faith. A firefighter has died. The funeral procession makes its way up St. Laurent Boulevard. The Laudate Dominum of the 20th century’s greatest composer pays tribute to him. Without commentary, didacticism or ostentation, the film is a history lesson of the last century: the red light district, the eloquent Jean Drapeau, the young Queen Elizabeth greeting the crowd and Tex Lecor shouting “Aux armes Québécois !” Here are kids dreaming of hockey glory, here’s the Jacques-Cartier market bursting with fresh produce, and the department stores downtown thronged with Christmas shoppers. -

Founded in 1939 Under the Aegis of Scotsman John Grierson, Pioneering Theorist and Practitioner of the Documentary Form, The

Founded in 1939 under the aegis of Scotsman John Grierson , pioneering theorist and practitioner of the documentary form, the National Film Board was initially put in the service of war propaganda. Two years later, the addition to its ranks of Grierson’s countryman Norman McLaren would instigate the NFB’s second elemental thrust: technically adventurous, audaciously whimsical animation. These two interwoven threads have permeated the Film Board’s productions ever since, giving us formally innovative works that nonetheless edify. NFB films are fun, entertaining, and favor the dramatic over the didactic. We present, drawn from the shelves of Oddball Archives, what can only pretend at a cross-section of NFB’s voluminous output: explorations from the subatomic to the outer reaches of space, with a dose of human-scale drama and sheer flights of fancy. Pas de deux (1968) B+W 13 min. by Norman McLaren Set against a black ground, two graceful dancers become pure embodiments of light. Using optical superimposition, McLaren multiplies the figures, transforming live action into his own brand of kinetics. Beautifully choreographed and shot, hauntingly scored (featuring the United Folk Orchestra of Romania ), hypnotic and unforgettable. Cosmic Zoom (1968) Color 8 min. by Eva Szasz A fantastic, “continuous” voyage from a rowboat on the Ottawa river, upward and outward to a grand view of galactic flotsam, then back inwards through a rivulet of blood in the tip of a mosquito’s proboscis, to examine an atomic nucleus. Remade a decade later by Charles and Ray Eames (Powers of Ten ) with narration (and its jumping-off point moved to Chicago), then again as an Imax movie ( Cosmic Voyage ) with Morgan Freeman , Cosmic Zoom is where it all began. -

NORMAN MCLAREN RETROSPECTIVE at Moma

The Museum of Modern Art 50th Anniversary NO. 7 no FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE NORMAN MCLAREN RETROSPECTIVE AT MoMA As part of NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA: A RETROSPECTIVE, Norman McLaren, master animator and founder of the Board's an imation unit in 1941, will be honored with a retrospective of virtually all the films he made at NFBC. Part One of MoMA's NFBC Retrospective, ANIMATION, runs from January 22 through February 16, and presents a survey of 150 animated films. Five programs of the extraordinary and influential work of Norman McLaren will be presented from February 12 through 16. "Animation came to the National Film Board of Canada in 1941 with the person of Norman McLaren. In 1943, after having recruited George Dunning, Jim MacKay and Grant Munro, it was McLaren who was put in charge of the first animation workshop. The earliest films were craftsmanlike, having a more utilitarian than aesthetic character. After the war the time of the artist came about. The spirit and goals of the animation unit changed; the styles and techniques became more and more refined leading to today's sophisticated animation." —Louise Beaudet, Head of Animation Department, Cinematheque quebecoise, Montreal "Norman McLaren (Stirling, Scotland, 1914) completed his first abstract films in 1933 while a student at the Glasgow School of Art, Here he attracted the attention of John Grierson, who invited the young man upon graduation to make promotional films for the General Post Office in London. McLaren worked for the GPO from 1936 until 1939 when, at the onset of war, he moved to New York. -

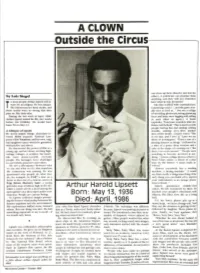

Outside the Circus

A CLOWN .-----Outside the Circus------. ous close-up faces dissolve one into the by Lois Siegel other). A politician can promise them anything, and they will not remember o most people Arthur Lipsett will al- , later what he has promised." ways be an enigma. He was unique. The film is fllied with contradictions: THis idiosyncracies bred myths,. and (stuttering voice) " ... and the game is re these myths were so strong that they. ally nice to look at..." (we see a collage pass on, like fairy-tales. of wrestling photos picturing grimacing During the last week of April, 1986, faces and hefty men tugging and pulling Arthur Lipsett ended his life, two weeks at each other in agony). A bomb before his birthday. He would have explodes: "Everyone wonders what the been 50 on May 13. future will behold." This is intercut with people having fun and smiling: smiling A Glimpse of Lipsett mouths, smiling eyes ... then another He loved simple things: chocolate-co shot of the bomb... (man's voice) "This vered M&M peanuts; National Lam is my line, and I love it." Later we see poon's film Vacation, and his own, orig shots of newspapers: "There's sort of a inal spaghetti sauce which he garnished passing interest in things." (followed by with pickles and olives. c: a shot of a pastry-shop window and a He discovered the power of mm at a ~ cake in the shape of a smiling cat). "But young age and set about creating high {l there's no real concern." "People seem () voltage collages.