Download Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cinemati • TRADE NEWS • Full Implementation of Law Due in 0C Private Labs Suffer From

CINEMAti • TRADE NEWS • Full Implementation of law due in 0C Private labs suffer from MONTREAL - By the end of gross; and the factors which Once the regulations are ap NF B IT Fproductions October, the Quebec Cabinet should determine the 'house proved, the Cabinet will then 15 projects since the begin is expected to have approved nut' or the cost of operating a promulgate the articles of the MONTREAL - Figures recently the final version of the regula theatre. law which are pertinent. released by the National Film ning of the Broadcast Fund for tions of the Cinema Law. Ap Guerin does not foresee any Board to Sonolab's president budgets totalling 532,528,000. proval of the 140 articles of the parts of the law being set aside, Andre Fleury reveal for the Of this amount, the NFB spent regulations will permit prom For articles concerning film and commented that the first time the ventilation of in $4,399,000 internally on tech ulgation of the remaining arti distribution as defined in the cinema dossier is one of the vestments made by the NFB on nical services while it spent cles of the law which was pass regulations see page 44, minister's priorities. Richard productions involving Telefilm only 565,000 on the same ser ed by the National Assembly has already announced that he Canada and are sure to fuel the vices in the private sector. on June 22, 1983. will not stand for re-election, long-standing battle involving Emo explains in her letter to The final, public consulta Other briefs presented at the but has promised to see the the Board and the private-sec Fleury that the Board's policy tion on the regulations took hearings dealt with video-cas Cinema Law completed before tor service houses. -

NATIONAL FILM BOARD of CANADA FEATURED at Moma

The Museum off Modern Art 50th Anniversary NO. 16 ID FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 3, 1981 DOCUMENTARY FILMS FROM THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA FEATURED AT MoMA NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA: A RETROSPECTIVE is a three-part tribute presented by The Museum of Modern Art in recog nition of NFBC's 41 years Of exceptional filmmaking. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY FILMS, running from March 26 through May 12 in the Museum's Roy and Niuta Titus Auditorium, will trace the develop ment of the documentary form at NFBC, and will be highlighted by a selection of some of the finest films directed by Donald Brittain, whose work has won wide acclaim and numerous awards. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY will get off to an auspicious start with twelve of Donald Brittain's powerful and unconventional portraits of exceptional individuals. Best known in this country for "Volcano: An Inquiry Into The Life and Death of Malcolm Lowry" (1976), Brittain brings his personal stamp of creative interpretation to such subjects as America's love affair with the automobile in "Henry Ford's America" (1976) ; the flamboyant Lord Thompson of Fleet Street (the newspaper baron who just sold the cornerstone of his empire, The London Times) in "Never A Backward Step" (1966); Norman Bethune, the Canadian poet/ doctor/revolutionary who became a great hero in China when he marched with Mao ("Bethune" 1964); and the phenomenal media hysteria sur rounding the famous quintuplets in "The Diorme Years" (1979) . "Memo randum" (1965) accompanies a Jewish glazier from Tcronto when he takes his son back to the concentration camp where he was interned, an emotion al and historical pilgrimage of strong impact and sensitivity. -

May 6–15, 2011 Festival Guide Vancouver Canada

DOCUMENTARY FILM FESTIVAL MAY 6–15, 2011 FESTIVAL GUIDE VANCOUVER CANADA www.doxafestival.ca facebook.com/DOXAfestival @doxafestival PRESENTING PARTNER ORDER TICKETS TODAY [PAGE 5] GET SERIOUSLY CREATIVE Considering a career in Art, Design or Media? At Emily Carr, our degree programs (BFA, BDes, MAA) merge critical theory with studio practice and link you to industry. You’ll gain the knowledge, tools and hands-on experience you need for a dynamic career in the creative sector. Already have a degree, looking to develop your skills or just want to experiment? Join us this summer for short courses and workshops for the public in visual art, design, media and professional development. Between May and August, Continuing Studies will off er over 180 skills-based courses, inspiring exhibits and special events for artists and designers at all levels. Registration opens March 31. SUMMER DESIGN INSTITUTE | June 18-25 SUMMER INSTITUTE FOR TEENS | July 4-29 Table of Contents Tickets and General Festival Info . 5 Special Programs . .15 The Documentary Media Society . 7 Festival Schedule . .42 Acknowledgements . 8 Don’t just stand there — get on the bus! Greetings from our Funders . .10 Essay by John Vaillant . 68. Welcome from DOXA . 11 NO! A Film of Sexual Politics — and Art Essay by Robin Morgan . 78 Awards . 13 Youth Programs . 14 SCREENINGS OPEning NigHT: Louder Than a Bomb . .17 Maria and I . 63. Closing NigHT: Cave of Forgotten Dreams . .21 The Market . .59 A Good Man . 33. My Perestroika . 73 Ahead of Time . 65. The National Parks Project . 31 Amnesty! When They Are All Free . -

Film Reference Guide

REFERENCE GUIDE THIS LIST IS FOR YOUR REFERENCE ONLY. WE CANNOT PROVIDE DVDs OF THESE FILMS, AS THEY ARE NOT PART OF OUR OFFICIAL PROGRAMME. HOWEVER, WE HOPE YOU’LL EXPLORE THESE PAGES AND CHECK THEM OUT ON YOUR OWN. DRAMA 1:54 AVOIR 16 ANS / TO BE SIXTEEN 2016 / Director-Writer: Yan England / 106 min / 1979 / Director: Jean Pierre Lefebvre / Writers: Claude French / 14A Paquette, Jean Pierre Lefebvre / 125 min / French / NR Tim (Antoine Olivier Pilon) is a smart and athletic 16-year- An austere and moving study of youthful dissent and old dealing with personal tragedy and a school bully in this institutional repression told from the point of view of a honest coming-of-age sports movie from actor-turned- rebellious 16-year-old (Yves Benoît). filmmaker England. Also starring Sophie Nélisse. BACKROADS (BEARWALKER) 1:54 ACROSS THE LINE 2000 / Director-Writer: Shirley Cheechoo / 83 min / 2016 / Director: Director X / Writer: Floyd Kane / 87 min / English / NR English / 14A On a fictional Canadian reserve, a mysterious evil known as A hockey player in Atlantic Canada considers going pro, but “the Bearwalker” begins stalking the community. Meanwhile, the colour of his skin and the racial strife in his community police prejudice and racial injustice strike fear in the hearts become a sticking point for his hopes and dreams. Starring of four sisters. Stephan James, Sarah Jeffery and Shamier Anderson. BEEBA BOYS ACT OF THE HEART 2015 / Director-Writer: Deepa Mehta / 103 min / 1970 / Director-Writer: Paul Almond / 103 min / English / 14A English / PG Gang violence and a maelstrom of crime rock Vancouver ADORATION A deeply religious woman’s piety is tested when a in this flashy, dangerous thriller about the Indo-Canadian charismatic Augustinian monk becomes the guest underworld. -

A SALUTE to the NATIONAL FILM BOARD of CANADA Includes Sixteen Films Made Between

he Museum of Modern Art 1^ 111 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart Mo, 38 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Tuesday, April 25, 1967 On the occasion of The Canadian Centennial Week in New York, the Department of Film of The Museum of Modem Art will present A SALUTE TO THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA. Sixteen films produced by the National Film Board will be shown daily at the Museum from May U through May V->, except on Wednesdays. The program will be inaugu rated with a special screening for an invited audience on the evening of May 3j pre sented by The Consul General of Canada and The Canada Week Committee in association with the Museum. The National Film Board of Canada was established in 1939, with John Grierson, director of the British General Post Office film unit and leading documentary film producer, as Canada's first Government Film Commissioner, Its purpose is-to Jjiitdate and promote the production and distribution of films in the-uational int^rest^ \i\ par« ticular, films designed to interpret Canada to -Canadians and to other nations. Uniquely, each of its productions is available for showing in Canada as well as . abroad* Experimentation in all aspects of film-making has been actively continued and encouraged by the National Film Board. Funds are set aside for experiments, and all filmmakers are encouraged to attempt new techniques. Today the National Film Board of Canada produces more than 100 motion pictures each year with every film made in both English and French versions. -

Building Resilience Through Partnership

BUILDING RESILIENCE THROUGH PARTNERSHIP 2019-2020 ANNUAL REPORT TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 HIGHLIGHTS 9 ACHIEVEMENTS 11 ABOUT US 14 MESSAGES MANAGEMENT DISCUSSION 18 AND ANALYSIS INDUSTRY AND 19 ECONOMIC CONDITIONS CORPORATE 28 PLAN DELIVERY ATTRACT ADDITIONAL FUNDING 29 AND INVESTMENT EVOLVE OUR FUNDING 33 ALLOCATION APPROACH OPTIMIZE OUR 45 OPERATIONAL CAPABILITY ENHANCE THE VALUE 50 OF THE “CANADA” AND “TELEFILM” BRANDS 57 FINANCIAL REVIEW 64 RISK MANAGEMENT CORPORATE SOCIAL 66 RESPONSIBILITY 70 TALENT FUND 81 GOVERNANCE FINANCIAL 95 STATEMENTS ADDITIONAL 117 INFORMATION TELEFILM CANADA / 2019-2020 ANNUAL REPORT 1 The Canadian industry and audiences embraced female voices and HIGHLIGHTS Indigenous expression in fiscal year 2019-2020. Telefilm remained committed to greater representation in the films we support and to bringing Canadian creativity to the world. LOOKING TO THE FUTURE, our vision is for Telefilm and Canada to strengthen their role of Partner of Choice—creating and building ties, expanding opportunities and deepening impact. BRINGING CANADIAN CREATIVITY TO THE WORLD The Canada-Norway coproduction THE BODY REMEMBERS WHEN THE WORLD BROKE OPEN, directed by KATHLEEN HEPBURN and ELLE-MÁIJÁ TAILFEATHERS, received praise around the world— premiering at the Berlin Film Festival in 2019, selected as “REMARKABLE” a New York Times Critic’s Pick and being called “remarkable” by the Los Angeles Times. The film went on to be picked up ★★★★★ by Ava DuVernay’s ARRAY releasing for U.S and international. levelFilm distributed the film in Canada, while Another World LOS ANGELES TIMES Entertainment handled Norway. TELEFILM CANADA / 2019-2020 ANNUAL REPORT 2 HIGHLIGHTS BRINGING CANADIAN CREATIVITY TO THE WORLD MONIA CHOKRI’s debut feature filmLA FEMME DE WINNER MON FRÈRE (A Brother’s Love), which she both wrote COUP DE CŒUR AWARD and directed, premiered at the Cannes Film Festival CANNES opening the Un Certain Regard section, bringing home FILM FESTIVAL the jury’s Coup de Cœur award. -

CFDC Is Having a Good Year . . . Quadrant Films Announces Shoot

FunnEUJs CFDC is having a good year . duced in Vancouver by Werner Aellen Voluntary quota system an At least as far as recouping goes. The for Image Flow Productions in 16mm nounced by Secretary of State Corporation is only one-third through color. As for A Quiet Day in Belfast, "it Secretary of State Hugh Faulkner, the fiscal year, yet it has already gotten Famous Players, Odeon and Canadian- back more than half of the money it looks shaky" according to the CFDC; and they have yet to reach a decision on owned distribution companies an expected to. (Figures are confiden nounced a voluntary quota system in tial . .) Ted Rouse of the Toronto Patrick Loubert's Amusement Season in Red. He is still working on the rewrite. late July. The agreement has four major office estimates that almost 95 per cent parts: of the money coming back is from the Deadlines for submissions are as fol 1. Canadian 35 mm feature films pro French sector. Kamouraska, J'ai Men lows: duced or dubbed in English are guaran Voyage, La Mort d'un Biicheron and — September 10th for the October teed two weeks' theatre time in Mont Rowdyman are already in the recouping meeting real, Toronto and Vancouver. The res- stage. Wedding In White may join them — October 12th for the November ponsiblity for this is divided by Famous // it gets a television sale; and the films meeting Players (2/3 proportion) and Odeon the CFDC is very hopeful about are — December 7th for low-budget cat (1/3 proportion). Paperback Hero, The Pyx and Get Back. -

Canadian Films: What Are We to Make of Them?

Canadian Films: What Are We to Make of Them? By Gerald Pratley Spring 1998 Issue of KINEMA This technically fine picture was shot in British Columbia, but care seems to have been taken toeradicate any sign of Canadian identity in the story’s setting, which is simply generic North American. Film critic Derek Elley in his review of Mina Shum’s Drive, She Said in Variety, Dec. 22, 1997. NO MATTER to what segment of society individuals may belong within the public at large most of those interested in the arts are contemplating what to make of Canadian cinema. Among indigent artists, out- of-work actors, struggling writers, publishers and bookshop proprietors, theatregoers and movie enthusiasts, the question being asked is, what do we expect from Canadian movies? The puzzle begins when audiences, after being subjected to a barrage of media publicity and a frenzy of flag waving, which would have us believe that Canadian movies and tv programmes are among the best in the world, discover they are mostly embarrassingly bad. Except that is, films made in Québec. Yet even here the decline into worthlessness over the past twoyears has become apparent. It is noticeable that, when the media in the provinces other than Québec talk about Canadian films, they are seldom thinking of those in French. This means that we are forced, whentalking about Canadian cinema, into a form of separation because Québec film making is so different from ”ours”, making it impossible to generalize over Canadian cinema as a whole. If we are to believe everything the media tells us then David Cronenberg, whose work is morbid, Atom Egoyan, whose dabblings leave much to be desired, Guy Maddin, who is lost in his own dreams, and Patricia Rozema, who seldom seems to know what she is doing, are among the world’s leading filmmakers. -

Ing Lonely Boy

If the word documentary is synonymous with Canada, and the NFB is synonymous with Canadian documentary, it is impossible to consider the NFB, and particularly its fabled Unit B team, without one of its core members, Wolf Koenig. An integral part of the "dream team," he worked with, among others, Colin Low, Roman Kroitor, Terence Macartney-Filgate and unit head Tom Daly, as part of the NFB's most prolific and innovative ensemble. Koenig began his career as a splicer before moving on to animator, cameraman, director and producer, responsible for much of the output of the renowned Candid Eye series produced for CBC-TV between 1958 and 1961. Among Unit B's greatest achievements is Lonely Boy (1962), which bril- liantly captured the phenomenon of megastar mania before anyone else, and con- tinues to be screened worldwide. I had the opportunity to "speak" to Wolf Koenig in his first Internet interview, a fitting format for a self-professed tinkerer who made a career out of embracing the latest technologies. He reflects on his days as part of Unit B, what the term documentary means to him and the process of mak- ing Lonely Boy. What was your background before joining the NFB? One day, in early May 1948, my father got a call from a neighbour down the road — Mr. Merritt, the local agricultur- In 1937, my family fled Nazi Germany and came to Canada, al representative for the federal department of agriculture — just in the nick of time. After a couple of years of wonder- who asked if "the boy" could come over with the tractor to ing what he should do, my father decided that we should try out a new tree—planting machine. -

The Film Imagine an Angel Who Memorized All the Sights and Sounds of a City

The film Imagine an angel who memorized all the sights and sounds of a city. Imagine them coming to life: busy streets full of people and vehicles, activity at the port, children playing in yards and lanes, lovers kissing in leafy parks. Then recall the musical accompaniment of the past: Charles Trenet, Raymond Lévesque, Dominique Michel, Paul Anka, Willie Lamothe. Groove to an Oscar Peterson boogie. Dream to the Symphony of Psalms by Stravinsky. That city is Montreal. That angel guarding the sights and sounds is the National Film Board of Canada. The combined result is The Memories of Angels, Luc Bourdon’s virtuoso assembly of clips from 120 NFB films of the ’50s and ’60s. The Memories of Angels will charm audiences of all ages. It’s a journey in time, a visit to the varied corners of Montreal, a tribute to the vitality of the city and a wonderful cinematic adventure. It recalls Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire in which angels flew over and watched the citizens of Berlin. It has the same sense of ubiquity, the same flexibility, the sense of dreamlike freedom allowing us to fly from Place Ville- Marie under construction to the workers in a textile factory or firemen at work. Underpinning the film is Stravinsky’s music, representing love, hope and faith. A firefighter has died. The funeral procession makes its way up St. Laurent Boulevard. The Laudate Dominum of the 20th century’s greatest composer pays tribute to him. Without commentary, didacticism or ostentation, the film is a history lesson of the last century: the red light district, the eloquent Jean Drapeau, the young Queen Elizabeth greeting the crowd and Tex Lecor shouting “Aux armes Québécois !” Here are kids dreaming of hockey glory, here’s the Jacques-Cartier market bursting with fresh produce, and the department stores downtown thronged with Christmas shoppers. -

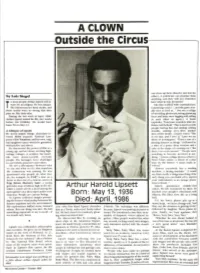

Outside the Circus

A CLOWN .-----Outside the Circus------. ous close-up faces dissolve one into the by Lois Siegel other). A politician can promise them anything, and they will not remember o most people Arthur Lipsett will al- , later what he has promised." ways be an enigma. He was unique. The film is fllied with contradictions: THis idiosyncracies bred myths,. and (stuttering voice) " ... and the game is re these myths were so strong that they. ally nice to look at..." (we see a collage pass on, like fairy-tales. of wrestling photos picturing grimacing During the last week of April, 1986, faces and hefty men tugging and pulling Arthur Lipsett ended his life, two weeks at each other in agony). A bomb before his birthday. He would have explodes: "Everyone wonders what the been 50 on May 13. future will behold." This is intercut with people having fun and smiling: smiling A Glimpse of Lipsett mouths, smiling eyes ... then another He loved simple things: chocolate-co shot of the bomb... (man's voice) "This vered M&M peanuts; National Lam is my line, and I love it." Later we see poon's film Vacation, and his own, orig shots of newspapers: "There's sort of a inal spaghetti sauce which he garnished passing interest in things." (followed by with pickles and olives. c: a shot of a pastry-shop window and a He discovered the power of mm at a ~ cake in the shape of a smiling cat). "But young age and set about creating high {l there's no real concern." "People seem () voltage collages. -

Unbridgeable Barriers: the Holocaust in Canadian Cinema by Jeremy

Unbridgeable Barriers: The Holocaust in Canadian Cinema by Jeremy Maron A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Mediations Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2011, Jeremy Maron Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de Pedition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre riterence ISBN: 978-0-494-83210-3 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-83210-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation.