Landscape of Denial: Arthur

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Broadcasting Taste: a History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media a Thesis in the Department of Co

Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English-Canadian Media A Thesis In the Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Communication Studies) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada December 2016 © Zoë Constantinides, 2016 CONCORDIA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES This is to certify that the thesis prepared By: Zoë Constantinides Entitled: Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media and submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in Communication Studies complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by the final examining committee: __________________________________________ Beverly Best Chair __________________________________________ Peter Urquhart External Examiner __________________________________________ Haidee Wasson External to Program __________________________________________ Monika Kin Gagnon Examiner __________________________________________ William Buxton Examiner __________________________________________ Charles R. Acland Thesis Supervisor Approved by __________________________________________ Yasmin Jiwani Graduate Program Director __________________________________________ André Roy Dean of Faculty Abstract Broadcasting Taste: A History of Film Talk, International Criticism, and English- Canadian Media Zoë Constantinides, -

Short Film Programme

SHORT FILM PROGRAMME If you’d like to see some of the incredible short films produced in Canada, please check out our description of the Short Film Programme on page 50, and contact us for advice and assistance. IM Indigenous-made films (written, directed or produced by Indigenous artists) Films produced by the National Film Board of Canada NFB CLASSIC ANIMATIONS BEGONE DULL CARE LA FAIM / HUNGER THE STREET Norman McLaren, Evelyn Lambart Peter Foldès 1973 11 min. Caroline Leaf 1976 10 min. 1949 8 min. Rapidly dissolving images form a An award-winning adaptation of a An innovative experimental film satire of self-indulgence in a world story by Canadian author Mordecai consisting of abstract shapes and plagued by hunger. This Oscar- Richler about how families deal with colours shifting in sync with jazz nominated film was among the first older relatives, and the emotions COSMIC ZOOM music performed by the Oscar to use computer animation. surrounding a grandmother’s death. Peterson Trio. THE LOG DRIVER’S WALTZ THE SWEATER THE BIG SNIT John Weldon 1979 3 min. Sheldon Cohen 1980 10 min. Richard Condie 1985 10 min. The McGarrigle sisters sing along to Iconic author Roch Carrier narrates A wonderfully wacky look at two the tale of a young girl who loves to a mortifying boyhood experience conflicts — global nuclear war and a dance and chooses to marry a log in this animated adaptation of his domestic quarrel — and how each is driver over more well-to-do suitors. beloved book The Hockey Sweater. resolved. Nominated for an Oscar. -

NATIONAL FILM BOARD of CANADA FEATURED at Moma

The Museum off Modern Art 50th Anniversary NO. 16 ID FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE March 3, 1981 DOCUMENTARY FILMS FROM THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA FEATURED AT MoMA NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA: A RETROSPECTIVE is a three-part tribute presented by The Museum of Modern Art in recog nition of NFBC's 41 years Of exceptional filmmaking. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY FILMS, running from March 26 through May 12 in the Museum's Roy and Niuta Titus Auditorium, will trace the develop ment of the documentary form at NFBC, and will be highlighted by a selection of some of the finest films directed by Donald Brittain, whose work has won wide acclaim and numerous awards. PART TWO: DOCUMENTARY will get off to an auspicious start with twelve of Donald Brittain's powerful and unconventional portraits of exceptional individuals. Best known in this country for "Volcano: An Inquiry Into The Life and Death of Malcolm Lowry" (1976), Brittain brings his personal stamp of creative interpretation to such subjects as America's love affair with the automobile in "Henry Ford's America" (1976) ; the flamboyant Lord Thompson of Fleet Street (the newspaper baron who just sold the cornerstone of his empire, The London Times) in "Never A Backward Step" (1966); Norman Bethune, the Canadian poet/ doctor/revolutionary who became a great hero in China when he marched with Mao ("Bethune" 1964); and the phenomenal media hysteria sur rounding the famous quintuplets in "The Diorme Years" (1979) . "Memo randum" (1965) accompanies a Jewish glazier from Tcronto when he takes his son back to the concentration camp where he was interned, an emotion al and historical pilgrimage of strong impact and sensitivity. -

A SALUTE to the NATIONAL FILM BOARD of CANADA Includes Sixteen Films Made Between

he Museum of Modern Art 1^ 111 West 53 Street, New York, N.Y. 10019 Circle 5-8900 Cable: Modernart Mo, 38 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Tuesday, April 25, 1967 On the occasion of The Canadian Centennial Week in New York, the Department of Film of The Museum of Modem Art will present A SALUTE TO THE NATIONAL FILM BOARD OF CANADA. Sixteen films produced by the National Film Board will be shown daily at the Museum from May U through May V->, except on Wednesdays. The program will be inaugu rated with a special screening for an invited audience on the evening of May 3j pre sented by The Consul General of Canada and The Canada Week Committee in association with the Museum. The National Film Board of Canada was established in 1939, with John Grierson, director of the British General Post Office film unit and leading documentary film producer, as Canada's first Government Film Commissioner, Its purpose is-to Jjiitdate and promote the production and distribution of films in the-uational int^rest^ \i\ par« ticular, films designed to interpret Canada to -Canadians and to other nations. Uniquely, each of its productions is available for showing in Canada as well as . abroad* Experimentation in all aspects of film-making has been actively continued and encouraged by the National Film Board. Funds are set aside for experiments, and all filmmakers are encouraged to attempt new techniques. Today the National Film Board of Canada produces more than 100 motion pictures each year with every film made in both English and French versions. -

Ing Lonely Boy

If the word documentary is synonymous with Canada, and the NFB is synonymous with Canadian documentary, it is impossible to consider the NFB, and particularly its fabled Unit B team, without one of its core members, Wolf Koenig. An integral part of the "dream team," he worked with, among others, Colin Low, Roman Kroitor, Terence Macartney-Filgate and unit head Tom Daly, as part of the NFB's most prolific and innovative ensemble. Koenig began his career as a splicer before moving on to animator, cameraman, director and producer, responsible for much of the output of the renowned Candid Eye series produced for CBC-TV between 1958 and 1961. Among Unit B's greatest achievements is Lonely Boy (1962), which bril- liantly captured the phenomenon of megastar mania before anyone else, and con- tinues to be screened worldwide. I had the opportunity to "speak" to Wolf Koenig in his first Internet interview, a fitting format for a self-professed tinkerer who made a career out of embracing the latest technologies. He reflects on his days as part of Unit B, what the term documentary means to him and the process of mak- ing Lonely Boy. What was your background before joining the NFB? One day, in early May 1948, my father got a call from a neighbour down the road — Mr. Merritt, the local agricultur- In 1937, my family fled Nazi Germany and came to Canada, al representative for the federal department of agriculture — just in the nick of time. After a couple of years of wonder- who asked if "the boy" could come over with the tractor to ing what he should do, my father decided that we should try out a new tree—planting machine. -

The Film Imagine an Angel Who Memorized All the Sights and Sounds of a City

The film Imagine an angel who memorized all the sights and sounds of a city. Imagine them coming to life: busy streets full of people and vehicles, activity at the port, children playing in yards and lanes, lovers kissing in leafy parks. Then recall the musical accompaniment of the past: Charles Trenet, Raymond Lévesque, Dominique Michel, Paul Anka, Willie Lamothe. Groove to an Oscar Peterson boogie. Dream to the Symphony of Psalms by Stravinsky. That city is Montreal. That angel guarding the sights and sounds is the National Film Board of Canada. The combined result is The Memories of Angels, Luc Bourdon’s virtuoso assembly of clips from 120 NFB films of the ’50s and ’60s. The Memories of Angels will charm audiences of all ages. It’s a journey in time, a visit to the varied corners of Montreal, a tribute to the vitality of the city and a wonderful cinematic adventure. It recalls Wim Wenders’ Wings of Desire in which angels flew over and watched the citizens of Berlin. It has the same sense of ubiquity, the same flexibility, the sense of dreamlike freedom allowing us to fly from Place Ville- Marie under construction to the workers in a textile factory or firemen at work. Underpinning the film is Stravinsky’s music, representing love, hope and faith. A firefighter has died. The funeral procession makes its way up St. Laurent Boulevard. The Laudate Dominum of the 20th century’s greatest composer pays tribute to him. Without commentary, didacticism or ostentation, the film is a history lesson of the last century: the red light district, the eloquent Jean Drapeau, the young Queen Elizabeth greeting the crowd and Tex Lecor shouting “Aux armes Québécois !” Here are kids dreaming of hockey glory, here’s the Jacques-Cartier market bursting with fresh produce, and the department stores downtown thronged with Christmas shoppers. -

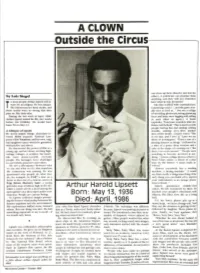

Outside the Circus

A CLOWN .-----Outside the Circus------. ous close-up faces dissolve one into the by Lois Siegel other). A politician can promise them anything, and they will not remember o most people Arthur Lipsett will al- , later what he has promised." ways be an enigma. He was unique. The film is fllied with contradictions: THis idiosyncracies bred myths,. and (stuttering voice) " ... and the game is re these myths were so strong that they. ally nice to look at..." (we see a collage pass on, like fairy-tales. of wrestling photos picturing grimacing During the last week of April, 1986, faces and hefty men tugging and pulling Arthur Lipsett ended his life, two weeks at each other in agony). A bomb before his birthday. He would have explodes: "Everyone wonders what the been 50 on May 13. future will behold." This is intercut with people having fun and smiling: smiling A Glimpse of Lipsett mouths, smiling eyes ... then another He loved simple things: chocolate-co shot of the bomb... (man's voice) "This vered M&M peanuts; National Lam is my line, and I love it." Later we see poon's film Vacation, and his own, orig shots of newspapers: "There's sort of a inal spaghetti sauce which he garnished passing interest in things." (followed by with pickles and olives. c: a shot of a pastry-shop window and a He discovered the power of mm at a ~ cake in the shape of a smiling cat). "But young age and set about creating high {l there's no real concern." "People seem () voltage collages. -

A Supercut of Supercuts: Aesthetics, Histories, Databases

A Supercut of Supercuts: Aesthetics, Histories, Databases PRACTICE RESEARCH MAX TOHLINE ABSTRACT CORRESPONDING AUTHOR: Max Tohline The genealogies of the supercut, which extend well past YouTube compilations, back Independent scholar, US to the 1920s and beyond, reveal it not as an aesthetic that trickled from avant-garde [email protected] experimentation into mass entertainment, but rather the material expression of a newly-ascendant mode of knowledge and power: the database episteme. KEYWORDS: editing; supercut; compilation; montage; archive; database TO CITE THIS ARTICLE: Tohline, M. 2021. A Supercut of Supercuts: Aesthetics, Histories, Databases. Open Screens, 4(1): 8, pp. 1–16. DOI: https://doi.org/10.16995/os.45 Tohline Open Screens DOI: 10.16995/os.45 2 Full Transcript: https://www.academia.edu/45172369/Tohline_A_Supercut_of_Supercuts_full_transcript. Tohline Open Screens DOI: 10.16995/os.45 3 RESEARCH STATEMENT strong patterning in supercuts focuses viewer attention toward that which repeats, stoking uncritical desire for This first inklings of this video essay came in the form that repetition, regardless of the content of the images. of a one-off blog post I wrote seven years ago (Tohline While critical analysis is certainly possible within the 2013) in response to Miklos Kiss’s work on the “narrative” form, the supercut, broadly speaking, naturally gravitates supercut (Kiss 2013). My thoughts then comprised little toward desire instead of analysis. more than a list; an attempt to add a few works to Armed with this conclusion, part two sets out to the prehistory of the supercut that I felt Kiss and other discover the various roots of the supercut with this supercut researchers or popularizers, like Tom McCormack desire-centered-ness, and other pragmatics, as a guide. -

Unbridgeable Barriers: the Holocaust in Canadian Cinema by Jeremy

Unbridgeable Barriers: The Holocaust in Canadian Cinema by Jeremy Maron A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Cultural Mediations Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2011, Jeremy Maron Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de Pedition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre riterence ISBN: 978-0-494-83210-3 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-83210-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

CÀPSULES DEL TEMPS. Els Films-Collage D' Arthur Lipsett

16 de gener de 2014, 20h C ÀPSULES DEL TEMPS. Els films-collage d’ Arthur Lipsett Very Nice, Very Nice, Arthur Lipsett, 1961, vídeo, 6' ● 21-87, A. Lipsett, 1964, 16mm, 9’ ● Perceptual Learning, A. Lipsett, 1965, vídeo, 11’ ● Free Fall, A. Lipsett, 1964, vídeo, 9’ ● A Trip Down Memory Lane, A. Lipsett, 1965, vídeo, 12’ ● Fluxes, A. Lipsett, 1968, 16mm, 23’ ● Lipsett Diaries, Theodore Ushev, 2010, 35mm, 14' ● Un programa de Gonzalo de Lucas a figura d’Arthur Lipsett ocupa un dels marges més En comptes d'això, el tipus de juxtaposició d'imatges i, L originals i apassionants del muntatge i el film freqüentment, de sons i imatges que proposen tenen collage. La seva obra, que va fascinar cineastes tan més en comú amb les relacions arbitràries i la lògica dels diferents com Kubrick, Brakhage o George Lucas, va somnis del surrealisme, amb la ironia iconoclasta del quedar interrompuda pels problemes mentals del dadaisme i amb les conjuncions inconnexes del collage i cineasta i el turment que el va abocar al suïcidi, als 46 el fotomuntatge. anys. Lipsett havia començat realitzant collages sonors, que després va traslladar a les seves peces enigmàtiques i [...] El tipus de manipulació de les imatges que duu a brillants produïdes per el National Film Board de terme s'apropa a la complexitat formal i densitat Canadà: combinacions d’imatges i sons, en films de metafòrica del treball de Conner, mentre que, igual que reciclatge i deconstrucció, assajos visuals irònics i Vanderbeek, empra la banda sonora per reproduir la sarcàstics sobre el consumisme o crítiques dels mass heterogloxia de la vida urbana contemporània i els media, segons ritmes jazzístics o sincopats que van mitjans de masses. -

Sounds Like Canada Longfield, Michael Cineaction; 2009; 77; CBCA Complete Pg- 9

Sounds Like Canada Longfield, Michael Cineaction; 2009; 77; CBCA Complete Pg- 9 Sounds Like Canada A REEXAMINATION OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF CANADIAN CINEMA-VERITE MICHAEL LONGFIELD It is well known that within the kingdom of nonfiction film, the For example, in Canada, the National Film Board's federal order of "direct documentary", regardless of genus (cinema- mandate and funding opportunities, guided by producer Tom verite, Direct Cinema, Free Cinema, Candid Eye), did not emerge Daly's benevolent leadership at Unit B, created a unique kind of fully formed from the brow of any of its progenitors no matter documentary laboratory. Daly, who had apprenticed with John how organic its evolution may appear in hindsight. It developed Grierson and Stuart Legg at the Board during the war years, was through a confluence of factors (technical, aesthetic, authorial) a gifted film editor, and his years at the helm of Unit B offered marshaled by filmmakers in France, the U.S., England, and those more ambitious or visionary filmmakers a strong sense of Canada. Throughout the mid 50s and early 60s we see an structure. Beyond the cinematic texts themselves, trouble-shoot- exchange of ideas, equipment, and even personnel between ing new technical and aesthetic challenges offered unparalleled these camps. Technology alone did not enable these films, and training to the filmmakers working under Daly, and those skills there is evident a large variation in terms of how the technolo- would be exported abroad. French director Jean Rouch perhaps gy was deployed. not-so-famously credited his partnership with NFB director-cam- Pour la suite du monde (1963) •• «s<5r *.•• • OSK Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

1. Learning the Craft

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2017-02 The Documentary Art of Filmmaker Michael Rubbo Jones, D.B. University of Calgary Press http://hdl.handle.net/1880/51804 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 4.0 International Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca THE DOCUMENTARY ART OF FILMMAKER MICHAEL RUBBO D. B. Jones ISBN 978-1-55238-871-6 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. COPYRIGHT NOTICE: This open-access work is published under a Creative Commons licence. This means that you are free to copy, distribute, display or perform the work as long as you clearly attribute the work to its authors and publisher, that you do not use this work for any commercial gain in any form, and that you in no way alter, transform, or build on the work outside of its use in normal academic scholarship without our express permission.