An Overview of the Chinese Wine Market and the Main Wine Exporting Countries to China

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

China Consumer Close-Up

January 13, 2015 The Asian Consumer: A new series Equity Research China Consumer Close-up The who, what and why of China’s true consumer class Few investing challenges have proven more elusive than understanding the Chinese consumer. Efforts to translate the promise of an emerging middle class into steady corporate earnings have been uneven. In the first of a new series on the Asian consumer, we seek to strip the problem back to the basics: Who are the consumers with spending power, what drives their consumption and how will that shift over time? The result is a new approach that yields surprising results. Joshua Lu Goldman Sachs does and seeks to do business with +852-2978-1024 [email protected] companies covered in its research reports. As a result, Goldman Sachs (Asia) L.L.C. investors should be aware that the firm may have a conflict of interest that could affect the objectivity of this report. Sho Kawano Investors should consider this report as only a single factor +81(3)6437-9905 [email protected] Goldman Sachs Japan Co., Ltd. in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Becky Lu Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html. +852-2978-0953 [email protected] Analysts employed by non- US affiliates are not registered/ Goldman Sachs (Asia) L.L.C. qualified as research analysts with FINRA in the U.S. January 13, 2015 Asia Pacific: Retail Table of contents PM Summary: A holistic view of the Asian consumer 3 China’s cohort in a regional context (a preview of India and Indonesia) 8 What they are buying and what they will buy next: Tracking 7 consumption desires 11 Seven consumption desires in focus 14 1. -

Spirits Selection by Concours Mondial 2020 Prize List

Spirits Selection by Concours Mondial 2020 Prize list Armenia Belgium Gold Medals Gold Medals V & M 3 Yo (Brandy) Filliers Barrel Aged Genever 8 Years Old (Genever) Producer: Armenia Wine Factory LLC Producer: Filliers Distillery Australia Ginbee's (Gin) Producer: Dard-Dard Srl Silver Medals Gouden Carolus Single Malt (Whisky) Coffee Storm (Flavoured Rum) Producer: Brouwerij Het Anker - Stokerij De Queensland Molenberg Producer: Milton Distillery Pty LTD Le passionné Rhumantic (Flavoured Rum) Producer: Fabian Pierre - Rhumantic Austria Pastis Patinette (Aniseed) Gold Medals Producer: Distillerie Gervin Distillery Krauss London Dry Gin Bergamot Pepper Plus Oultre Distillery Bitter (Bitter) (Gin) Producer: Plus Oultre Distillery Producer: Distillery Krauss GmbH Shack Pecans Spiced Rum (Spiced Rum) G+ Classic Edition Gin (Gin) Producer: Plan B International BVBA Producer: Distillery Krauss GmbH Silver Medals G+ Lemon Edition Gin (Gin) Producer: Distillery Krauss GmbH Amaretto Noblesse (Liquor-Cream) Producer: Noblesse 1882 SPRL Silver Medals Belgian Owl - Passion (Whisky) Distillery Krauss Distilled Anise (Aniseed) Producer: The Owl Distillery S.A. Producer: Distillery Krauss GmbH Biercine (Liquor-Cream) G+ Flower Edition Gin (Gin) Producer: Brass des Légendes sprl-Distillerie de Producer: Distillery Krauss GmbH Biercée Cosmik Pure Diamond Vodka (Vodka) Producer: Wave Distil srl Dr.Clyde Classic Rum (Rum) Producer: Dr.Clyde Distillery Filliers Barrel Aged Genever 17 Years Old (Genever) Producer: Filliers Distillery Gin.be (Gin) Producer: -

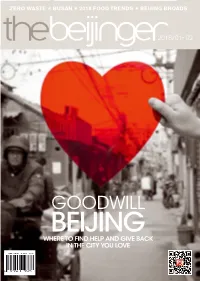

Goodwill Beijing Where to Find Help and Give Back in the City You Love

ZERO WASTE BUSAN 2018 FOOD TRENDS BEIJING BROADS 2018/01- 02 GOODWILL BEIJING WHERE TO FIND HELP AND GIVE BACK IN THE CITY YOU LOVE 1 JAN/FEB 2018 为您打造 A Publication of ZERO WASTE BUSAN 2018 FOOD TRENDS BEIJING BROADS 出版发行: 云南出版集团 云南科技出版社有限责任公司 地址: 云南省昆明市环城西路609号, 云南新闻出版大楼2306室 责任编辑: 欧阳鹏, 张磊 书号: 978-7-900747-65-5 GOODWILL BEIJING WHERE TO FIND HELP AND GIVE BACK IN THE CITY YOU LOVE Since 2001 | 2001年创刊 thebeijinger.com A Publication of 广告代理: 北京爱见达广告有限公司 地址: 北京市朝阳区关东店北街核桃园30号 孚兴写字楼C座5层, 100020 Advertising Hotline/广告热线: 5941 0368, [email protected] Since 2006 | 2006年创刊 Beijing-kids.com Managing Editor Tom Arnstein Editors Kyle Mullin, Tracy Wang Copy Editor Amber De La Haye Contributors Jeremiah Jenne, Andrew Killeen, Robynne Tindall, 国际教育 · 家庭生活 · 社区活动 Will Griffith 寄宿教育 True Run Media Founder & CEO Michael Wester Boarding School Education Owner & Co-Founder Toni Ma Art Director Susu Luo Designer Vila Wu Production Manager Joey Guo Content Marketing Manager Robynne Tindall Marketing Director Lareina Yang Events & Brand Manager Mu Yu 封面故事 亲子假期怎么过? Marketing Team Helen Liu, Cindy Zhang, Echo Wang Staycation with Kids in Beijing 2016年11月刊 1 HR Manager Tobal Loyola HR & Admin Officer Cao Zheng Since 2012 | 2012年创刊 Jingkids.com Finance & Admin Manager Judy Zhao Accountants Vicky Cui, Susan Zhou Digital Development Director Alexandre Froger IT Support Specialist Yan Wen Photographer Uni You 国际教育·家庭生活·都市资讯 Sales Director Sheena Hu Account Managers Winter Liu, Wilson Barrie, Olesya Sedysheva, Veronica Wu, Sharon Shang, Fangfang Wang Sales Supporting -

MODELING LUXURY WINE PREFERENCE: a STUDY of BUSINESS TRAVELERS from CHINA by Mark Mark Keene

MODELING LUXURY WINE PREFERENCE: A STUDY OF BUSINESS TRAVELERS FROM CHINA by Mark Mark Keene A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Hospitality and Tourism Management West Lafayette, Indiana December 2018 2 THE PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL STATEMENT OF COMMITTEE APPROVAL Dr. Carl A. Behnke, Chair School of Hospitality and Tourism Management Dr. Liping A. Cai School of Hospitality and Tourism Management Dr. Susan E. Gordon School of Hospitality and Tourism Management Dr. Chantal Levesque-Bristol Department of Educational Studies Approved by: Dr. Jonathan Day Head of the Graduate Program 3 This research is dedicated to my husband, Dr. Bryan C. Keene. Our eternally-shared values of love, quality time with family and friends, and adventure through life experiences has withstood this test and will continue to define our―and our children’s―life. 4 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS There are three types of acknowledgments that I would like to mention: spiritual, mentorly, and familial. First, all that I achieve, including this research, is due to the grace of God. Second, I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to my mentor and committee chair, Dr. Carl Behnke. His guidance and mentorship throughout the program, with a notable emphasis on the steps just preceding the defense, have been invaluable. I am grateful for the friendship that he and Sara have extended. I would also like to thank my other committee members: Drs. Liping Cai, Susan Gordon, and Chantal Levesque-Bristol. Dr. Liping Cai kindly bestowed his expansive but honed multi-cultural perspective that guided the purpose of this research. -

Annual Report DBX ETF Trust

May 31, 2021 Annual Report DBX ETF Trust Xtrackers Harvest CSI 300 China A-Shares ETF (ASHR) Xtrackers Harvest CSI 500 China A-Shares Small Cap ETF (ASHS) Xtrackers MSCI All China Equity ETF (CN) Xtrackers MSCI China A Inclusion Equity ETF (ASHX) DBX ETF Trust Table of Contents Page Shareholder Letter ....................................................................... 1 Management’s Discussion of Fund Performance ............................................. 3 Performance Summary Xtrackers Harvest CSI 300 China A-Shares ETF ........................................... 6 Xtrackers Harvest CSI 500 China A-Shares Small Cap ETF .................................. 8 Xtrackers MSCI All China Equity ETF .................................................... 10 Xtrackers MSCI China A Inclusion Equity ETF ............................................ 12 Fees and Expenses ....................................................................... 14 Schedule of Investments Xtrackers Harvest CSI 300 China A-Shares ETF ........................................... 15 Xtrackers Harvest CSI 500 China A-Shares Small Cap ETF .................................. 20 Xtrackers MSCI All China Equity ETF .................................................... 28 Xtrackers MSCI China A Inclusion Equity ETF ............................................ 33 Statements of Assets and Liabilities ........................................................ 42 Statements of Operations ................................................................. 43 Statements of Changes in Net -

A Study of Characteristics of Female Chinese Tourists Who Participate in New Zealand Wine Tourism

A Study of Characteristics of Female Chinese Tourists Who Participate in New Zealand Wine Tourism Lin Huang A DISSERATION SUBMITED TO AUCKLAND UNIVERITY OF TECHNOLOGY IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF INTERNATIONAL HOSPITALITY MANAGEMENT (MIHM) 2014 FACULTY OF CULTURE AND SOCIETY SCHOOL OF HOSPITALITY AND TOURISM PRIMARY SUPERVISOR: DR CHARLES JOHNSTON Table of Contents List of Figures .......................................................................................................................................... v List of Tables ........................................................................................................................................... v Attestation of Authorship ...................................................................................................................... vi Ethics Approval ..................................................................................................................................... vii Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................................. viii Confidential Material ............................................................................................................................. ix Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... x 1 Introduction ................................................................................................................................... -

Cocktails Mocktails Beer & Cider

COCKTAILS Jasmine Lychee Martini 22 House infused Jasmine Tea Vodka, Paraiso Lychee Liqueur and Pineapple juice Mango Campari Spritz 22 Campari, Mango juice, sparkling wine and soda Guava Margarita 22 el Jimador Reposado Tequila, Guava juice, fresh lime juice Amaretto Sour 22 Disaronno amaretto, fresh lemon juice, egg white Chrysanthemum Old Fashioned 22 House infused Chrysanthemum Rum, bitters and syrup Cinnamon Apple Martini 22 House infused cinnamon Vodka, Schnapps apple pucker, apple juice, cinnamon syrup The Dragon's Eye 26 Paraiso Lychee Liqueur, Kweichow Moutai Chinese spirit, lychee, fresh lemon Oolong Mojito 22 Bacardi Superior White Rum, fresh lime, fresh mints, Oolong syrup Strawberry Daiquiri 22 Bacardi Superior White Rum, Suntory Rubis Strawberry, fresh strawberry Espresso Martini 22 Ketel One Vodka, Kahlua, Espresso MOCKTAILS Seasonal Fruit Cup 13 Seasonal fresh fruit, fruit juice (Please ask our friendly staff) Traditional Lemonade 13 Fresh lemon juice, honey, soda water Virgin Oolong Mojito 17 Fresh lime, fresh mints, Oolong syrup Virgin Strawberry Caipirinha 17 Fresh strawberry, fresh lime, apple juice BEER & CIDER Cascade 'Premium Light' Tasmania 9 James Boag’s 'Premium' Tasmania 11 Crown Lager Victoria 11 Tsing Tao China 11 Corona 'Extra' Mexico 12 Heineken Holland (locally brewed under license) 12 Stella Artois Belgium (locally brewed under license) 12 Kirin 'Ichiban' Japan 13 Little Creatures 'Pipsqueak' Apple Cider Adelaide Hills 12 1 WINE BY THE GLASS SPARKLING - 120ml NV Chandon Brut Yarra Valley, Victoria 17 2016 -

Hearing on China in Space: a Strategic Competition?

HEARING ON CHINA IN SPACE: A STRATEGIC COMPETITION? HEARING BEFORE THE U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION ONE HUNDRED SIXTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION THURSDAY, APRIL 25, 2019 Printed for use of the United States-China Economic and Security Review Commission Available via the World Wide Web: www.uscc.gov UNITED STATES-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION WASHINGTON: 2019 U.S.-CHINA ECONOMIC AND SECURITY REVIEW COMMISSION CAROLYN BARTHOLOMEW, CHAIRMAN ROBIN CLEVELAND, VICE CHAIRMAN Commissioners: HON. CARTE P. GOODWIN MICHAEL A. MCDEVITT ROY D. KAMPHAUSEN HON. JAMES M. TALENT THEA MEI LEE MICHAEL R. WESSEL KENNETH LEWIS The Commission was created on October 30, 2000 by the Floyd D. Spence National Defense Authorization Act for 2001 § 1238, Public Law No. 106-398, 114 STAT. 1654A-334 (2000) (codified at 22 U.S.C. § 7002 (2001), as amended by the Treasury and General Government Appropriations Act for 2002 § 645 (regarding employment status of staff) & § 648 (regarding changing annual report due date from March to June), Public Law No. 107-67, 115 STAT. 514 (Nov. 12, 2001); as amended by Division P of the “Consolidated Appropriations Resolution, 2003,” Pub L. No. 108-7 (Feb. 20, 2003) (regarding Commission name change, terms of Commissioners, and responsibilities of the Commission); as amended by Public Law No. 109- 108 (H.R. 2862) (Nov. 22, 2005) (regarding responsibilities of Commission and applicability of FACA); as amended by Division J of the “Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2008,” Public Law Nol. 110-161 (December 26, 2007) (regarding responsibilities of the Commission, and changing the Annual Report due date from June to December); as amended by the Carl Levin and Howard P. -

About Beef Grilling Beijing's Burgeoning Burger Scene

AL FRESCO VENUES VEGGIE BURGERS 2018 IN MUSIC SO FAR 2018/05- 06 all about beef Grilling Beijing's Burgeoning Burger Scene 1 MAY/JUN 2018 为您打造 A Publication of AL FRESCO VENUES VEGGIE BURGERS 2018 IN MUSIC SO FAR 出版发行: 云南出版集团 云南科技出版社有限责任公司 all 地址: 云南省昆明市环城西路609号, about beef Grilling Beijing's 云南新闻出版大楼2306室 Burgeoning Burger Scene 责任编辑: 欧阳鹏, 张磊 书号: 978-7-900747-68-6 Since 2001 | 2001年创始 thebeijinger.com A Publication of 广告代理: 北京爱见达广告有限公司 地址: 北京市朝阳区关东店北街核桃园30号 孚兴写字楼C座5层, 100020 Advertising Hotline/广告热线: 5941 0368, [email protected] Since 2006 | 2006年创始 Beijing-kids.com Managing Editor Tom Arnstein Editors Kyle Mullin, Tracy Wang Contributors Jeremiah Jenne, Andrew Killeen, Robynne Tindall, Will Griffith, Tautvile Daugelaite 国际教育 · 家庭生活 · 社区活动 True Run Media Founder & CEO Michael Wester Owner & Co-Founder Toni Ma Art Director Susu Luo 家庭教育: 父爱如山 Designer Vila Wu Father's Deep Love Production Manager Joey Guo Content Marketing Manager Robynne Tindall Marketing Director Lareina Yang Events & Brand Manager Mu Yu Marketing Team Helen Liu, Echo Wang, Evan Zhang 封面故事 HR Manager Tobal Loyola 旅行的意义 Experience of a Lifetime 2016年11月刊 1 HR & Admin Officer Cao Zheng Finance & Admin Manager Judy Zhao Since 2012 | 2012年创始 Jingkids.com Accountants Vicky Cui, Susan Zhou Digital Development Director Alexandre Froger IT Support Specialist Yan Wen Photographer Uni You Sales Director Sheena Hu Account Managers Winter Liu, Wilson Barrie, Olesya Sedysheva, 国际教育·家庭生活·都市资讯 Veronica Wu, Sharon Shang, Violet Xu Sales Supporting Manager Gladys Tang 难忘的研学旅行 Unforgettable -

Spirits Selection 2015 PRIZE LIST

Concours Mondial – Spirits Selection 2015 PRIZE LIST Barbados Bulgaria Gold Medals Silver Medals Mount Gay 1703 Old Cask Selection Rum (Rum) - Mount Gay Distilleries Alambic Rakia (Brandy) - Black Sea Gold Limited Chile Silver Medals Mount Gay Eclipse Rum (Rum) - Mount Gay Distilleries Limited Gold Medals Pisco Malpaso Reservado - Valle de Curicó (Pisco) - Sociedad Agricola Belgium Hacienda Mal Paso y Cía Pisco Monte Fraile - Valle de Elqui (Pisco) - Capel Grand Gold Medals Shack Rum Spiced (Spiced Rum) - PlanB International Silver Medals Pisco Mistral Nobel Reservado - Valle de Elqui (Pisco) - Compañía Gold Medals Pisquera de Chile S.A. BUSS N°509 White Rain Gin (Gin) - PlanB International China Double You Gin (Gin) - Brouwerij & Alcoholstokerij Wilderen Grand Gold Medals Filliers Dry Gin 28 Tangerine (Gin) - Filliers Graanstokerij NV Feitian Kweichou Moutai Liquor 2014 (Baijiu) - Kweichou Moutai Co., Ltd Silver Medals Han Lin 2014 (Baijiu) - Henan Baiquan Chun Liquor Industry Co., Ltd 1836 Belgian Organic Vodka (Vodka) - Distillerie Radermacher SA Jinsha Jiang Jiu 10 2009 (Baijiu) - Guizhou Jin Sha Jiao Jiu Liquor BUSS N°509 Persian Peach Gin (Gin) - PlanB International Industry Co., Ltd Lidu Broomcorn 1955 1987 (Baijiu) - Jiangxi Lidu liquor Industry Co., Ltd Edelweiss Gin - Het Waasland (Gin) - Brouwerij Verhofstede Maotai Bird's Nest Ordinary Liquor 2013 (Baijiu) - Beijng Shengshi Dadian Brazil Liquor Industry Group Tunzhihu (Baijiu) - Sichuan Tuopai Shede Liquor Industry Gold Medals Turtle Fairy Cave (Dan Xia) 2005 (Baijiu) - Guizhou -

Market Integration in the Chinese Beer and Wine Markets: Evidence from Stationarity Test

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: http://www.researchgate.net/publication/282862403 Market Integration in the Chinese Beer and Wine Markets: Evidence from Stationarity Test CHAPTER · OCTOBER 2015 READS 3 4 AUTHORS, INCLUDING: Chi Keung Marco Lau Zhibin Lin Northumbria University Northumbria University 43 PUBLICATIONS 89 CITATIONS 11 PUBLICATIONS 3 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE David Boansi University of Bonn 16 PUBLICATIONS 18 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Available from: Zhibin Lin Retrieved on: 17 October 2015 Market Integration in the Chinese Beer and Wine Markets: Evidence from Stationarity Test Marco Chi Keung Lau1*, Zhibin Lin1, David Boansi2, Jie Ma1 1. Newcastle Business School, Northumbria University, City Campus East, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE7 7QP United Kingdom. 2. Department of Economic and Technological Change Centre for Development Research (ZEF), Bonn, Germany. *corresponding author: [email protected] To cite this article: Lau, M. Lin, Z, Boansi, D. & Ma, J. (forthcoming). “Market Integration in the Chinese Beer and Wine Markets: Evidence from Stationarity Test”, in Ignazio Cabras, David Higgins, David Preece (eds), Brewing, Beer and Pubs: A Global Perspective, Palgrave Macmillan. Abstract Following the economic reform in China and subsequent economic growth, the country has witnessed interesting shifts in dimensions of supply in various subsectors. This has in one way or another, stimulated growth in national and per capita disposal incomes among other economic indicators. In particular, there has been rapid growth in both beer and wine consumption in the country. This chapter aims to examine the nature of the beer and wine industry. Specifically we investigate price related issues and the degree of integration of the Chinese beer and wine markets and the nature of price convergence/divergence across major markets. -

Der Markt Für Alkoholische Getränke in China Zielgruppenanalyse Im Rahmen Der Exportangebote Für Die Agrar- Und Ernährungswirtschaft / Oktober 2013

Der Markt für alkoholische Getränke in China Zielgruppenanalyse im Rahmen der Exportangebote für die Agrar- und Ernährungswirtschaft / Oktober 2013 www.bmelv.de/export INHALTSVERZEICHNIS Inhalt 1 Einleitung ................................................................................................................................................. 6 2 Management Summary ............................................................................................................................ 7 3 Überblick über Politik und Wirtschaft im Zielland ................................................................................. 10 3.1 Politischer Hintergrund .......................................................................................................................... 10 3.1.1 Geographische Lage ............................................................................................................................... 11 3.1.2 Demographische Daten .......................................................................................................................... 12 3.1.3 Stärkere Kontrollen in der Lebensmittelsicherheit ................................................................................ 14 3.2 Wirtschaft, Struktur und Entwicklung .................................................................................................... 15 3.2.1 Entwicklung des chinesischen Bruttoinlandsproduktes ......................................................................... 15 3.2.2 Einkommensverteilung .........................................................................................................................