MODELING LUXURY WINE PREFERENCE: a STUDY of BUSINESS TRAVELERS from CHINA by Mark Mark Keene

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

葡萄酒 House Pouring Wine

葡萄酒 House Pouring Wine 150ml 750ml 有气的葡萄酒 Sparkling Wine Glass Bottle SP101 Pol Remy Brut Nv (France) $12 $44 白葡萄酒 White Wine W201 Bellevie Pavillon Sauvignon Blanc (France) $11 $40 W202 Pierre Jean Colombard Chardonnay (France) $12 $44 W203 De Bortoli DB Family Selection $13 $50 Sauvignon Blanc (Australia) 红葡萄酒 Red Wine R301 Bellevie Pavillon Merlot (France) $11 $40 R302 Pierre Jean Merlot (France) $12 $44 R303 De Bortoli DB Family Selection $13 $50 Cabernet Sauvignon (Australia) 葡萄酒促销 Wine Promotion *Special deal with minimum purchase of 2 bottles house pouring wine to entitle to 15% discount off from the usual price listed above. Prices subjected to prevailing GST and Service Charge. 消费税与服务费另计。 All photos are meant for reference only. Presentation of dishes may vary without prior notice. 照片只供参考之用,摆设更改恕不作另行通知。 主酒单 Master Wine List 150ml 750ml 有气的葡萄酒 Sparkling Wine Glass Bottle SP101 Pol Remy Brut Nv (France) $12 $44 Pol Remy is produced in Burgundy, France from classic wine varieties perfect for the production of sparkling wine. It is light, fresh and fruity with aromas of apple and peach. With a delightfully easy-drinking style, it exudes aromas of creamy lemon and peach. The palate is gently off-dry and flows through to a satisfying finish. 香槟 Champagne CH102 Henri Abele Brut NV (France) $110 Pale golden colour with greenish highlights. Remarkably fine bubbles and a beautiful, persistent bead. Attractive and luscious, with hints of hawthorn and acacia blossoms as well as overtones of peach and apricot. Exceptional ripeness on the palate. Toasty, honey, and cinnamon flavours. This elegant cuvée has a full bodied, generous aftertaste. -

FTSE Publications

2 FTSE Russell Publications 01 October 2020 FTSE Value Stocks China A Share Indicative Index Weight Data as at Closing on 30 September 2020 Index weight Index weight Index weight Constituent Country Constituent Country Constituent Country (%) (%) (%) Agricultural Bank of China (A) 4.01 CHINA Fuyao Glass Group Industries (A) 1.43 CHINA Seazen Holdings (A) 0.81 CHINA Aisino Corporation (A) 0.52 CHINA Gemdale (A) 1.37 CHINA Shanghai Fosun Pharmaceutical Group (A) 1.63 CHINA Anhui Conch Cement (A) 3.15 CHINA GoerTek (A) 2.12 CHINA Shenwan Hongyuan Group (A) 1.11 CHINA AVIC Investment Holdings (A) 0.61 CHINA Gree Electric Appliances Inc of Zhuhai (A) 7.48 CHINA Shenzhen Overseas Chinese Town Holdings 0.66 CHINA Bank of China (A) 2.23 CHINA Guangdong Haid Group (A) 1.24 CHINA (A) Bank Of Nanjing (A) 1.32 CHINA Guotai Junan Securities (A) 1.99 CHINA Sichuan Chuantou Energy (A) 0.71 CHINA Bank of Ningbo (A) 2 CHINA Hangzhou Hikvision Digital Technology (A) 3.56 CHINA Tbea (A) 0.86 CHINA Beijing Dabeinong Technology Group (A) 0.56 CHINA Henan Shuanghui Investment & Development 1.49 CHINA Tonghua Dongbao Medicines(A) 0.59 CHINA China Construction Bank (A) 1.83 CHINA (A) Weichai Power (A) 2.09 CHINA China Life Insurance (A) 2.14 CHINA Hengtong Optic-Electric (A) 0.59 CHINA Wuliangye Yibin (A) 9.84 CHINA China Merchants Shekou Industrial Zone 1.03 CHINA Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (A) 3.5 CHINA XCMG Construction Machinery (A) 0.73 CHINA Holdings (A) Inner Mongolia Yili Industrial(A) 6.32 CHINA Xinjiang Goldwind Science&Technology (A) 0.74 -

Luzhou Laojiao Co., Ltd. 2018 Annual Report April 2019

2018 Annual Report of Luzhou Laojiao Co.,Ltd. Luzhou Laojiao Co., Ltd. 2018 Annual Report April 2019 1 2018 Annual Report of Luzhou Laojiao Co.,Ltd. Section I Important Statements, Contents and Definitions The Board of Directors, Board of Supervisors, directors, supervisors and senior management guarantee that the information presented in this report is free of any false records, misleading statements or material omissions, and shall Individually and together be legally liable for truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of its contents. Mr. Liu Miao, responsible person for the Company, Ms. Xie Hong, responsible person for accounting work and Mr. Yan Li, responsible person for the Company’s financial affairs (Accounting Supervisor) have warranted that the financial statements in this report are true and complete. Other directors attended the board meeting to deliberate this report by themselves except the following directors. Name of directors who did not Position of directors who did not Reason for not attending Name of attend the meeting in person attend the meeting in person the meeting in person deputies Liu Miao Chairman of the Board work Lin Feng Shen Caihong Director work Jiang Yuhui Affected by risks, uncertainties and assumptions, the forward-looking statements concerning business objectives and future plans made in this report based on the subjective assumptions and judgments of the future policies and economic conditions may be significantly different from the actual results. Such statements shall not be considered as virtual promises of the Company to investors, and the investors and relevant persons shall maintain adequate risk awareness and shall understand the differences between plans, forecasts and commitments. -

China Consumer Close-Up

January 13, 2015 The Asian Consumer: A new series Equity Research China Consumer Close-up The who, what and why of China’s true consumer class Few investing challenges have proven more elusive than understanding the Chinese consumer. Efforts to translate the promise of an emerging middle class into steady corporate earnings have been uneven. In the first of a new series on the Asian consumer, we seek to strip the problem back to the basics: Who are the consumers with spending power, what drives their consumption and how will that shift over time? The result is a new approach that yields surprising results. Joshua Lu Goldman Sachs does and seeks to do business with +852-2978-1024 [email protected] companies covered in its research reports. As a result, Goldman Sachs (Asia) L.L.C. investors should be aware that the firm may have a conflict of interest that could affect the objectivity of this report. Sho Kawano Investors should consider this report as only a single factor +81(3)6437-9905 [email protected] Goldman Sachs Japan Co., Ltd. in making their investment decision. For Reg AC certification and other important disclosures, see the Disclosure Becky Lu Appendix, or go to www.gs.com/research/hedge.html. +852-2978-0953 [email protected] Analysts employed by non- US affiliates are not registered/ Goldman Sachs (Asia) L.L.C. qualified as research analysts with FINRA in the U.S. January 13, 2015 Asia Pacific: Retail Table of contents PM Summary: A holistic view of the Asian consumer 3 China’s cohort in a regional context (a preview of India and Indonesia) 8 What they are buying and what they will buy next: Tracking 7 consumption desires 11 Seven consumption desires in focus 14 1. -

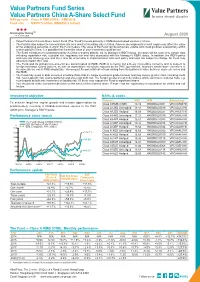

Value Partners Fund Series Value Partners China A-Share Select Fund

Value Partners Fund Series Value Partners China A-Share Select Fund NAV per unit : Class A RMB (CNH) – RMB19.19 Fund size : USD57.3 million (RMB393.2 million) HHH Morningstar RatingTM1 As at 31-08-2020 August 2020 • Value Partners China A-Share Select Fund (The “Fund”) invests primarily in RMB-denominated equities in China. • The Fund is also subject to concentration risk as a result of investing only in China. Adverse developments in such region may affect the value of the underlying securities in which the Fund invests. The value of the Fund can be extremely volatile and could go down substantially within a short period of time. It is possible that the entire value of your investment could be lost. • The Fund intends to invest predominantly in China A-shares directly, via its Manager’s RQFII quota. Investors will be subject to certain risks including repatriation risk, custodial risk, regulatory risk and risks associated with the Manager’s RQFII status. In addition, the RQFII policy and rules are relatively new and there may be uncertainty in implementation and such policy and rules are subject to change. All these may adversely impact the Fund. • The Fund and its primary investments are denominated in RMB. RMB is currently not a freely convertible currency and is subject to foreign exchange control policies, as well as repatriation restrictions imposed by the PRC government. Investors whose base currencies of investments are not in RMB should take into account the potential risk of loss arising from fluctuations in value between such currencies and the RMB. -

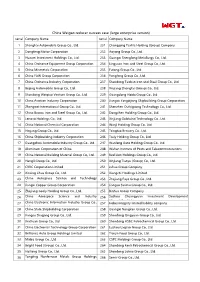

China Weigao Reducer Success Case (Large Enterprise Version) Serial Company Name Serial Company Name

China Weigao reducer success case (large enterprise version) serial Company Name serial Company Name 1 Shanghai Automobile Group Co., Ltd. 231 Chongqing Textile Holding (Group) Company 2 Dongfeng Motor Corporation 232 Aoyang Group Co., Ltd. 3 Huawei Investment Holdings Co., Ltd. 233 Guangxi Shenglong Metallurgy Co., Ltd. 4 China Ordnance Equipment Group Corporation 234 Lingyuan Iron and Steel Group Co., Ltd. 5 China Minmetals Corporation 235 Futong Group Co., Ltd. 6 China FAW Group Corporation 236 Yongfeng Group Co., Ltd. 7 China Ordnance Industry Corporation 237 Shandong Taishan Iron and Steel Group Co., Ltd. 8 Beijing Automobile Group Co., Ltd. 238 Xinjiang Zhongtai (Group) Co., Ltd. 9 Shandong Weiqiao Venture Group Co., Ltd. 239 Guangdong Haida Group Co., Ltd. 10 China Aviation Industry Corporation 240 Jiangsu Yangzijiang Shipbuilding Group Corporation 11 Zhengwei International Group Co., Ltd. 241 Shenzhen Oufeiguang Technology Co., Ltd. 12 China Baowu Iron and Steel Group Co., Ltd. 242 Dongchen Holding Group Co., Ltd. 13 Lenovo Holdings Co., Ltd. 243 Xinjiang Goldwind Technology Co., Ltd. 14 China National Chemical Corporation 244 Wanji Holding Group Co., Ltd. 15 Hegang Group Co., Ltd. 245 Tsingtao Brewery Co., Ltd. 16 China Shipbuilding Industry Corporation 246 Tasly Holding Group Co., Ltd. 17 Guangzhou Automobile Industry Group Co., Ltd. 247 Wanfeng Auto Holding Group Co., Ltd. 18 Aluminum Corporation of China 248 Wuhan Institute of Posts and Telecommunications 19 China National Building Material Group Co., Ltd. 249 Red Lion Holdings Group Co., Ltd. 20 Hengli Group Co., Ltd. 250 Xinjiang Tianye (Group) Co., Ltd. 21 CRRC Corporation Limited 251 Juhua Group Company 22 Xinxing Jihua Group Co., Ltd. -

Luzhou Laojiao Co., Ltd. 2020 Interim Report

2020 Interim Report of Luzhou Laojiao Co., Ltd. Luzhou Laojiao Co., Ltd. 2020 Interim Report August 2020 1 2020 Interim Report of Luzhou Laojiao Co., Ltd. Section I Important Statements, Contents and Definitions The Board of Directors, Board of Supervisors, as well as directors, supervisors and senior management other than the following directors, supervisors and senior management that have expressed dissent against this report guarantee that the information presented in this report is free of any false records, misleading statements or material omissions, and shall individually and together be legally liable for truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of its contents. Liu Miao, responsible person for the Company, Xie Hong, responsible person for accounting work and Yan Li, responsible person for the Company’s financial affairs (Accounting Supervisor) have warranted that the financial statements in this report are true and complete. All the directors attended the board meeting to deliberate this report by themselves. Affected by risks, uncertainties and assumptions, the forward-looking statements concerning business objectives and future plans made in this report based on the subjective assumptions and judgments of the future policies and economic conditions may be significantly different from the actual results. Such statements shall not be considered as virtual promises of the Company to investors, and the investors and relevant persons shall maintain adequate risk awareness and shall understand the differences between plans, forecasts and commitments. The Company has no interim dividend plan, either in the form of cash or stock. This Report has been prepared in both Chinese and English. Should there be any discrepancies or misunderstandings between the two versions, the Chinese version shall prevail. -

Spirits Selection by Concours Mondial 2020 Prize List

Spirits Selection by Concours Mondial 2020 Prize list Armenia Belgium Gold Medals Gold Medals V & M 3 Yo (Brandy) Filliers Barrel Aged Genever 8 Years Old (Genever) Producer: Armenia Wine Factory LLC Producer: Filliers Distillery Australia Ginbee's (Gin) Producer: Dard-Dard Srl Silver Medals Gouden Carolus Single Malt (Whisky) Coffee Storm (Flavoured Rum) Producer: Brouwerij Het Anker - Stokerij De Queensland Molenberg Producer: Milton Distillery Pty LTD Le passionné Rhumantic (Flavoured Rum) Producer: Fabian Pierre - Rhumantic Austria Pastis Patinette (Aniseed) Gold Medals Producer: Distillerie Gervin Distillery Krauss London Dry Gin Bergamot Pepper Plus Oultre Distillery Bitter (Bitter) (Gin) Producer: Plus Oultre Distillery Producer: Distillery Krauss GmbH Shack Pecans Spiced Rum (Spiced Rum) G+ Classic Edition Gin (Gin) Producer: Plan B International BVBA Producer: Distillery Krauss GmbH Silver Medals G+ Lemon Edition Gin (Gin) Producer: Distillery Krauss GmbH Amaretto Noblesse (Liquor-Cream) Producer: Noblesse 1882 SPRL Silver Medals Belgian Owl - Passion (Whisky) Distillery Krauss Distilled Anise (Aniseed) Producer: The Owl Distillery S.A. Producer: Distillery Krauss GmbH Biercine (Liquor-Cream) G+ Flower Edition Gin (Gin) Producer: Brass des Légendes sprl-Distillerie de Producer: Distillery Krauss GmbH Biercée Cosmik Pure Diamond Vodka (Vodka) Producer: Wave Distil srl Dr.Clyde Classic Rum (Rum) Producer: Dr.Clyde Distillery Filliers Barrel Aged Genever 17 Years Old (Genever) Producer: Filliers Distillery Gin.be (Gin) Producer: -

Luzhou Laojiao Co., Ltd. 2020 Annual Report April 2021

2020 Annual Report of Luzhou Laojiao Co., Ltd. Luzhou Laojiao Co., Ltd. 2020 Annual Report April 2021 1 2020 Annual Report of Luzhou Laojiao Co., Ltd. Section I Important Statements, Contents and Definitions The Board of Directors, Board of Supervisors, directors, supervisors and senior management guarantee that the information presented in this report is free of any false records, misleading statements or material omissions, and shall individually and together be legally liable for truthfulness, accuracy and completeness of its contents. Liu Miao, responsible person for the Company, Xie Hong, responsible person for accounting work and Yan Li, responsible person for the Company’s financial affairs (Accounting Supervisor) have warranted that the financial statements in this report are true, accurate and complete. Other directors attended the board meeting to deliberate this report by themselves except the following directors. Position of directors who Name of directors who did not Reason for not attending did not attend the meeting Name of deputies attend the meeting in person the meeting in person in person Wang Hongbo Director Work Lin Feng Tan Lili Independent Director Work Xu Guoxiang Qian Xu Director Work Liu Miao Ying Hanjie Director Work Liu Miao Affected by risks, uncertainties and assumptions, the forward-looking statements concerning business objectives and future plans made in this report based on the subjective assumptions and judgments of the future policies and economic conditions may be significantly different from the actual results. Such statements shall not be considered as virtual promises of the Company to investors, and the investors and relevant persons shall maintain adequate risk awareness and shall understand the differences between plans, forecasts and commitments. -

Goodwill Beijing Where to Find Help and Give Back in the City You Love

ZERO WASTE BUSAN 2018 FOOD TRENDS BEIJING BROADS 2018/01- 02 GOODWILL BEIJING WHERE TO FIND HELP AND GIVE BACK IN THE CITY YOU LOVE 1 JAN/FEB 2018 为您打造 A Publication of ZERO WASTE BUSAN 2018 FOOD TRENDS BEIJING BROADS 出版发行: 云南出版集团 云南科技出版社有限责任公司 地址: 云南省昆明市环城西路609号, 云南新闻出版大楼2306室 责任编辑: 欧阳鹏, 张磊 书号: 978-7-900747-65-5 GOODWILL BEIJING WHERE TO FIND HELP AND GIVE BACK IN THE CITY YOU LOVE Since 2001 | 2001年创刊 thebeijinger.com A Publication of 广告代理: 北京爱见达广告有限公司 地址: 北京市朝阳区关东店北街核桃园30号 孚兴写字楼C座5层, 100020 Advertising Hotline/广告热线: 5941 0368, [email protected] Since 2006 | 2006年创刊 Beijing-kids.com Managing Editor Tom Arnstein Editors Kyle Mullin, Tracy Wang Copy Editor Amber De La Haye Contributors Jeremiah Jenne, Andrew Killeen, Robynne Tindall, 国际教育 · 家庭生活 · 社区活动 Will Griffith 寄宿教育 True Run Media Founder & CEO Michael Wester Boarding School Education Owner & Co-Founder Toni Ma Art Director Susu Luo Designer Vila Wu Production Manager Joey Guo Content Marketing Manager Robynne Tindall Marketing Director Lareina Yang Events & Brand Manager Mu Yu 封面故事 亲子假期怎么过? Marketing Team Helen Liu, Cindy Zhang, Echo Wang Staycation with Kids in Beijing 2016年11月刊 1 HR Manager Tobal Loyola HR & Admin Officer Cao Zheng Since 2012 | 2012年创刊 Jingkids.com Finance & Admin Manager Judy Zhao Accountants Vicky Cui, Susan Zhou Digital Development Director Alexandre Froger IT Support Specialist Yan Wen Photographer Uni You 国际教育·家庭生活·都市资讯 Sales Director Sheena Hu Account Managers Winter Liu, Wilson Barrie, Olesya Sedysheva, Veronica Wu, Sharon Shang, Fangfang Wang Sales Supporting -

A Viga Ting Hin A

December 11, 2018 Food & Beverages Gan Bei: low inventory to support growth HINA C ■ We believe the China baijiu sector’s short-term slowdown has been priced in, and we consider the sector’s current valuation to be attractive. ■ Positive on the long-term outlook on product mix upgrades and channel reforms. Current tight channel inventory supports volume growth in 1H19F ■ We initiate coverage on China’s baijiu sector with an Overweight rating. Our top pick is Moutai. We have an Add call on Yanghe and Hold on Wuliangye. AVIGATING AVIGATING N Analyst(s) Lei YANG, CFA T (86) 21 6162 9676 E [email protected] FeiFei SUN T (86) 21 6162 5750 E [email protected] IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES, INCLUDING ANY REQUIRED RESEARCH CERTIFICATIONS, ARE PROVIDED AT THE Powered by END OF THIS REPORT. IF THIS REPORT IS DISTRIBUTED IN THE UNITED STATES IT IS DISTRIBUTED BY CGS-CIMB the EFA SECURITIES (USA), INC. AND IS CONSIDERED THIRD-PARTY AFFILIATED RESEARCH. Platform Navigating China Consumer Staples │Food & Beverages │December 11, 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Sector summary ............................................................................................................................. 5 Our market survey finds younger generation has started to drink baijiu ....................................... 9 China Baijiu sector overview ....................................................................................................... 13 Comparison of major baijiu players ............................................................................................ -

Rebalance Notes

The MarketGrader China All-Cap Growth Leaders – September 2020 Rebalance Notes The MarketGrader China All-Cap Growth Leaders Index completed its most recent semi-annual reconstitution and rebalance on September 18th, replacing 123 of its 200 constituents. This represented a turnover by count of 61.5%, which was significantly above its historical average of 44%. In fact, this turnover was the highest on record since the inception of the index at the start of 2008. The highest turnover by count prior to the most recent reconstitution was during the September 2017 reconstitution, when the Index turned over 58% of its constituents. Before discussing individual stock picks in the newly reconstituted Index, it is useful to examine the sector composition changes that resulted from the rebalance. Such changes were, of course, the result of MarketGrader’s bottom-up stock selection methodology based on our GARP analysis of the entire Chinese investable universe rather than a top-down sector weighting approach. This is important as the implied sector composition of the Index speaks to the financial condition of all of China’s economic sectors as a whole, based on the fundamentals of the companies within those sectors thereby affording investors a unique view of where quality growth in Chinese equities is available at a reasonable price. Sector Changes The table below summarizes the sector composition of the September 2020 reconstituted and rebalanced Index and compares it to the prior version of the Index that was selected during the March 2020 rebalance. Table 1. MarketGrader China All-Cap Growth Leaders Index: Sector Composition March 2020 September 2020 Sector Count Count Deletes Adds Change Turnover* Consumer Discretionary 28 13 24 9 -15 80% Consumer Staples 25 27 12 14 2 50% Energy 4 2 3 1 -2 67% Financials 27 18 19 10 -9 64% Health Care 26 34 14 22 8 60% Industrials 37 40 25 28 3 69% Materials 31 36 13 18 5 46% Technology 19 30 10 21 11 63% Utilities 3 0 3 0 -3 100% Total 200 200 123 123 0 Source: MarketGrader Research.