'Any Animal Whatever'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reflections on the Evolution of Morality Christine M. Korsgaard

Reflections on the Evolution of Morality Christine M. Korsgaard Harvard University1 All instincts that do not discharge themselves outwardly turn inward – this is what I call the internalization of man: thus it was that man first developed what was later called his “soul.” The entire inner world, originally as thin as if it were stretched between two membranes, expanded and extended itself, acquiring depth, breadth, and height, in the same measure as outward discharge was inhibited. - Nietzsche 1. Introduction In recent years there has been a fair amount of speculation about the evolution of morality, among scientists and philosophers alike. From both points of view, the question how our moral nature might have evolved is interesting because morality is one of the traditional candidates for a distinctively human attribute, something that makes us different from the other animals. From a scientific point of view, it matters whether there are any such attributes because of the special burden they seem to place on the theory of evolution. Beginning with Darwin’s own efforts in The Descent of Man, defenders of the theory of evolution have tried to show either that there are no genuinely distinctive human attributes – that is, that any differences between human beings and the other animals are a matter of degree – or that apparently distinctive human attributes can be explained in terms of the 1 Notes on this version are incomplete. Recommended supplemental reading: “The Activity of Reason,” APA Proceedings November 09, pp. 30-38. In a way, these papers are companion pieces, or at least their final sections are. -

EMDR Protocol Anger, Resentment and Revenge June 2014

EMDR Protocol Anger, Resentment and Revenge June 2014 Prologue In order to carry out the protocol in a responsible way, it is above all very important to have a thorough knowledge of the target group. Secondly, it is recommended to have participated in a workshop practising the protocol. And thirdly, one need knowledge of applying cognitive interweaves (as taught in an accredited EMDR training), because the presented procedure can also be used as cognitive interweave within the EMDR Standard protocol. Applying the protocol as a cognitive interweave: see addendum. Introduction The rationale of coping with Anger, Resentment and Revenge can be explained as follows: When people are reminded of disturbing memories or certain persons, it can lead to fierce emotions; sometimes “ the bucket will even overflow”. There are two kinds of emotions which can still be triggered by thinking of those negative experiences or persons. Therefore, there are also two buckets which can overflow. draw a bucket titled “Powerlessness and Fear” draw another bucket titled “Anger, Resentment and Revenge” One bucket contains all emotions concerning powerlessness, grief, fear and fright; all vulnerable, internalized emotions. The other bucket is filled with emotions like anger, resentment and sometimes even revenge; all ‘external directed’ emotions. When we look at the Powerlessness and Fear bucket, how full is it at this moment? When we look at the Anger bucket, how full is it at this moment? draw the levels indicated by the patient or let the patient draw the indicated levels Emptying which bucket would give the most relief? if the patient chooses the Powerlessness and Fear bucket, use the standard EMDR protocol if the patient chooses the Anger bucket, follow the next procedure Inventory To empty the bucket, we will not discuss the disturbing experiences you had, but we will focus on the persons who have treated you wrongly or who have damaged you. -

Ransom Is a Story of Vengeance Clashing with Grief.’ Discuss

‘Ransom is a story of vengeance clashing with grief.’ Discuss. In his lyrical novel, Ransom, David Malouf reimagines the final book of The Iliad, and in doing so, highlights the futility of countering grief with vengeance. He asserts the pointlessness of such vengeful actions, examines the role of the ‘rough world of men’ in creating it, and notes its cyclic nature, leaving many readers disheartened. However, Malouf also demonstrates how grief can be overcome with honourable actions. Malouf demonstrates to readers the uselessness of trying to assuage grief with acts of revenge. He introduces this concept right from the outset of the novel through his characterisation of Achilles. Malouf moves away from the traditional portrayal of Achilles as the most formidable of the Greeks and instead describes him as hollow and like a dead man. This new perspective of Achilles depicts him as lacking balance and feeling trapped in a clogging grey web due to his grief over the death of his soulmate Patroclus. Once Malouf describes Achilles’ barbaric actions in dragging around the corpse of Patroclus’ killer, Hector, it becomes clear to readers that Achilles is attempting to assuage his grief with violence and brutal, callous actions. Malouf uses imagery to depict Achilles as already dead himself as he continues to desecrate Hector’s body, by describing him as caked with dust like a man who has walked out of his grave. Thus, Malouf asserts how Achilles’ act of revenge has only wasted his spirit and left him feeling that it was never enough; being unable to overcome his pain at the loss of his friend. -

Evolution and Ethics 2

It is still disputed, however, why moral behavior extends beyond a close circle of kin and reciprocal relationships: e.g., most people think stealing from anyone is wrong, not just stealing from family and friends. For moral behavior to evolve as we understand it today, there likely had to be selective pressures that pushed people to disregard their own 1000wordphilosophy.com/2018/10/11/evolution- interests in favor of their group’s interest.[3] Exactly and-ethics/ how morality extended beyond this close circle is debated, with many theories under consideration.[4] Evolution and Ethics 2. What Should We Do? Author: Michael Klenk Suppose our ability to understand and apply moral Category: Ethics, Philosophy of Science rules, as typically understood, can be explained by Word Count: 999 natural selection. Does evolution explain which rules We often follow what are considered basic moral we should follow?[5] rules: don’t steal, don’t lie, help others when we can. Some answer, “yes!” “Greed captures the essence of But why do we follow these rules, or any rules the evolutionary spirit,” says the fictional character understood as “moral rules”? Does evolution explain Gordon Gekko in the 1987 film Wall Street: “Greed why? If so, does evolution have implications for … is good. Greed is right.”[6] which rules we should follow, and whether we genuinely know this? Gekko’s claims about what is good and right and what we ought to be comes from what he thinks we This essay explores the relations between evolution naturally are: we are greedy, so we ought to be and morality, including evolution’s potential greedy. -

The Evolution of Animal Play, Emotions, and Social Morality: on Science, Theology, Spirituality, Personhood, and Love

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 12-2001 The Evolution of Animal Play, Emotions, and Social Morality: On Science, Theology, Spirituality, Personhood, and Love Marc Bekoff University of Colorado Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/acwp_sata Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Behavior and Ethology Commons, and the Comparative Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Bekoff, M. (2001). The evolution of animal play, emotions, and social morality: on science, theology, spirituality, personhood, and love. Zygon®, 36(4), 615-655. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Evolution of Animal Play, Emotions, and Social Morality: On Science, Theology, Spirituality, Personhood, and Love Marc Bekoff University of Colorado KEYWORDS animal emotions, animal play, biocentric anthropomorphism, critical anthropomorphism, personhood, social morality, spirituality ABSTRACT My essay first takes me into the arena in which science, spirituality, and theology meet. I comment on the enterprise of science and how scientists could well benefit from reciprocal interactions with theologians and religious leaders. Next, I discuss the evolution of social morality and the ways in which various aspects of social play behavior relate to the notion of “behaving fairly.” The contributions of spiritual and religious perspectives are important in our coming to a fuller understanding of the evolution of morality. I go on to discuss animal emotions, the concept of personhood, and how our special relationships with other animals, especially the companions with whom we share our homes, help us to define our place in nature, our humanness. -

255 Investigations Into the Regulation of Dominance

255 INVESTIGATIONS INTO THE REGULATION OF DOMINANCE BEHAVIOUR AND OF THE DIVISION OF LABOUR IN BUMBLEBEE COLONIES (BOMBUS TERRESTRIS) by ADRIAAN VAN DOORN (ZoologicalInstitute II, Röntgenring10, 8700 Würzburg, West-Germany. Laboratory of ComparativePhysiology, Jan van Galenstraat40, 3572 LA Utrecht, The Netherlands*) SUMMARY During the first part of colony life Bombusterrestris queens have a strong regulating in- fluence on worker dominance. Dominant workers from queenless groups which are introduced into the colony are immediately dominated by the queen. They drop to a low position in the dominance hierarchy of the colony and may start foraging. The queen's dominance signal decreases at a certain, queen-specific time after she has switched to the laying of unfertilized eggs. Then an introduced dominant worker will supersede her and become the 'false-queen'. The false-queen apparently does not pro- duce the complete dominance signal since she usually has to carry out attacks on the workers to establish and maintain her dominance. The workers' flexibility with respect to the tasks they perform (foraging or nest duties) decreases with their age and in the course of colony development. House bees, especially those which have achieved a high position in the dominance hierarchy, are less inclined to change their tasks after removal of the foragers than foragers after removal of the house bees. But, in both cases, most of the work is taken over by young workers (less than 10 days old). Foragers which change to nest duties may substantial- ly increase their dominance and may become egglayers. Juvenile hormone (JH) treatment does not affect the division of labour, but it does influence the activity of the workers. -

Naturalizing Anthropomorphism: Behavioral Prompts to Our Humanizing of Animals

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 2007 Naturalizing Anthropomorphism: Behavioral Prompts to Our Humanizing of Animals Alexandra C. Horowitz Barnard College Marc Bekoff University of Colorado Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/acwp_habr Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Comparative Psychology Commons, and the Other Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Horowitz, A. C., & Bekoff, M. (2007). Naturalizing anthropomorphism: Behavioral prompts to our humanizing of animals. Anthrozoös, 20(1), 23-35. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Naturalizing Anthropomorphism: Behavioral Prompts to Our Humanizing of Animals Alexandra C. Horowitz1 and Marc Bekoff2 1 Barnard College 2 University of Colorado – Boulder KEYWORDS anthropomorphism, attention, cognitive ethology, dogs, humanizing animals, social play ABSTRACT Anthropomorphism is the use of human characteristics to describe or explain nonhuman animals. In the present paper, we propose a model for a unified study of such anthropomorphizing. We bring together previously disparate accounts of why and how we anthropomorphize and suggest a means to analyze anthropomorphizing behavior itself. We introduce an analysis of bouts of dyadic play between humans and a heavily anthropomorphized animal, the domestic dog. Four distinct patterns of social interaction recur in successful dog–human play: directed responses by one player to the other, indications of intent, mutual behaviors, and contingent activity. These findings serve as a preliminary answer to the question, “What behaviors prompt anthropomorphisms?” An analysis of anthropomorphizing is potentially useful in establishing a scientific basis for this behavior, in explaining its endurance, in the design of “lifelike” robots, and in the analysis of human interaction. -

Chemical Diplomacy in Male Tilapia: Urinary Signal Increases Sex Hormone and Decreases Aggression Received: 22 December 2015 João L

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Universidade do Algarve www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Chemical diplomacy in male tilapia: urinary signal increases sex hormone and decreases aggression Received: 22 December 2015 João L. Saraiva , Tina Keller-Costa, Peter C. Hubbard , Ana Rato & Adelino V. M. Canário Accepted: 30 June 2017 Androgens, namely 11-ketotestosterone (11KT), have a central role in male fsh reproductive Published: xx xx xxxx physiology and are thought to be involved in both aggression and social signalling. Aggressive encounters occur frequently in social species, and fghts may cause energy depletion, injury and loss of social status. Signalling for social dominance and fghting ability in an agonistic context can minimize these costs. Here, we test the hypothesis of a ‘chemical diplomacy’ mechanism through urinary signals that avoids aggression and evokes an androgen response in receiver males of Mozambique tilapia (Oreochromis mossambicus). We show a decoupling between aggression and the androgen response; males fghting their mirror image experience an unresolved interaction and a severe drop in urinary 11KT. However, if concurrently exposed to dominant male urine, aggression drops but urinary 11KT levels remain high. Furthermore, 11KT increases in males exposed to dominant male urine in the absence of a visual stimulus. The use of a urinary signal to lower aggression may be an adaptive mechanism to resolve disputes and avoid the costs of fghting. As dominance is linked to nest building and mating with females, the 11KT response of subordinate males suggests chemical eavesdropping, possibly in preparation for parasitic fertilizations. Androgens, synthesized mainly in the gonads and adrenal tissue1, are essential in vertebrate reproductive phys- iology and behaviour2. -

Aspects of Grief After a Violent Death

Aspects Of Grief After A Violent Death PERSONS WHO EXPERIENCE A HOMICIDE OR OTHER VIOLENT DEATH TEND TO: • Experience the impact of a sudden, unexpected, violent death with the possibility of a mutilated body, or no body at all. • Feel insecure, fearful, and have concerns for their safety. • Question their own basic beliefs and values about the importance of human life and behaviors. • Experience tremendous family stress as each person is grieving differently and each needs additional support. • Have a great deal of guilt over not having protected their loved one. • Feel the stigma of having a family member murdered, with people believing that only criminal types are murdered. • Lose their support system because people don’t know what to say and tend to stay away. • Be ignored, mistreated and receive little information from law enforcement officials assigned to the case. • Postpone their grief until after the trail and sentencing. • Find that whatever the sentence the murder receives, it is not enough to compensate for their loss. • Become victimized as a result of media coverage, for months and sometimes years after the death. • Experience intense anger, rage and sometimes revenge, which is overwhelming and produces within them fear of their own response. Concerns For Children Who Are Affected By A violent Death Fear of the Death: • Their Own Death • Death of Those Who Protect Them, Such as a Parent • Death of Friends and Loved Ones Anxiety About: • Being Left Alone • Sleeping Alone • Leaving the Surviving Family Members Regression: • Clingy, Irritable Behavior • Need for More Holding, Hugs and Nurturance • Possible Bedwetting Sleep Disorder: • Nightmares • Fear of Going to Bed • Not Able to Get to Sleep of Waking Throughout the Night Somatic Complaints: • Stomachaches, Headaches, Heartaches Eating Habit Changes Reliving The Violent Experience In Play Or In Memory. -

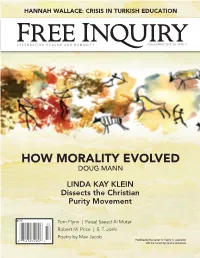

How Morality Evolved Doug Mann

HANNAH WALLACE: CRISIS IN TURKISH EDUCATION CELEBRATING REASON AND HUMANITY February/March 2019 Vol. 39 No. 2 HOW MORALITY EVOLVED DOUG MANN LINDA KAY KLEIN Dissects the Christian Purity Movement F/M 17 $5.95 CDN $5.95 US $5.95 Tom Flynn | Faisal Saeed Al Mutar 03 Robert M. Price | S. T. Joshi Poetry by Max Jacob Published by the Center for Inquiry in association 0 74470 74957 8 with the Council for Secular Humanism For many, mere atheism (the absence of belief in gods and the supernatural) or agnosticism (the view that such questions cannot be answered) aren’t enough. It’s liberating to recognize that supernatural beings are human creations … that there’s no such thing as “spirit” or “transcendence”… that people are undesigned, unintended, and responsible for themselves. But what’s next? Atheism and agnosticism are silent on larger questions of values and meaning. If Meaning in life is not ordained from on high, what small-m meanings can we work out among ourselves? If eternal life is an illusion, how can we make the most of our only lives? As social beings sharing a godless world, how should we coexist? For the questions that remain unanswered after we’ve cleared our minds of gods and souls and spirits, many atheists, agnostics, skeptics, and freethinkers turn to secular humanism. Secular. “Pertaining to the world or things not spiritual or sacred.” Humanism. “Any system of thought or action concerned with the interests or ideals of people … the intellectual and cultural movement … characterized by an emphasis on human interests rather than … religion.” — Webster’s Dictionary Secular humanism is a comprehensive, nonreligious life stance incorporating: A naturalistic philosophy A cosmic outlook rooted in science, and A consequentialist ethical system in which acts are judged not by their conformance to preselected norms but by their consequences for men and women in the world. -

Betrayal, Rejection, Revenge, and Forgiveness: an Interpersonal Script Approach

Betrayal, Rejection, Revenge, and Forgiveness: An Interpersonal Script Approach Julie Fitness Macquarie University Email: [email protected] In: Leary, M. (Ed.) (2001) Interpersonal rejection (pp. 73-103). New York: Oxford University Press. Acknowledgement: The author acknowledges the support of a Large ARC grant A79601552 in the writing of this chapter. 2 Introduction Throughout recorded human history, treachery and betrayal have been considered amongst the very worst offences people could commit against their kith and kin. Dante, for example, relegated traitors to the lowest and coldest regions of Hell, to be forever frozen up to their necks in a lake of ice with blizzards storming all about them, as punishment for having acted so coldly toward others. Even today, the crime of treason merits the most severe penalties, including capital punishment. However, betrayals need not involve issues of national security to be regarded as serious. From sexual infidelity to disclosing a friend’s secrets, betraying another person or group of people implies unspeakable disloyalty, a breach of trust, and a violation of what is good and proper. Moreover, all of us will suffer both minor and major betrayals throughout our lives, and most of us will, if only unwittingly, betray others (Jones & Burdette, 1994). The Macquarie Dictionary (1991) lists a number of different, though closely related, meanings of the term “to betray,” including to deliver up to an enemy, to be disloyal or unfaithful, to deceive or mislead, to reveal secrets, to seduce and desert, and to disappoint the hopes or expectations of another. Implicit in a number of these definitions is the rejection or discounting of one person by another; however, the nature of the relationship between interpersonal betrayal and rejection has not been explicitly addressed in the social psychological literature. -

Low Fundamental and Formant Frequencies Predict Fighting Ability

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Low fundamental and formant frequencies predict fghting ability among male mixed martial arts fghters Toe Aung1, Stefan Goetz2, John Adams2, Clint McKenna3, Catherine Hess1, Stiven Roytman2, Joey T. Cheng4, Samuele Zilioli2 & David Puts1* Human voice pitch is highly sexually dimorphic and eminently quantifable, making it an ideal phenotype for studying the infuence of sexual selection. In both traditional and industrial populations, lower pitch in men predicts mating success, reproductive success, and social status and shapes social perceptions, especially those related to physical formidability. Due to practical and ethical constraints however, scant evidence tests the central question of whether male voice pitch and other acoustic measures indicate actual fghting ability in humans. To address this, we examined pitch, pitch variability, and formant position of 475 mixed martial arts (MMA) fghters from an elite fghting league, with each fghter’s acoustic measures assessed from multiple voice recordings extracted from audio or video interviews available online (YouTube, Google Video, podcasts), totaling 1312 voice recording samples. In four regression models each predicting a separate measure of fghting ability (win percentages, number of fghts, Elo ratings, and retirement status), no acoustic measure signifcantly predicted fghting ability above and beyond covariates. However, after fght statistics, fght history, height, weight, and age were used to extract underlying dimensions of fghting ability via factor analysis, pitch and formant position negatively predicted “Fighting Experience” and “Size” factor scores in a multivariate regression model, explaining 3–8% of the variance. Our fndings suggest that lower male pitch and formants may be valid cues of some components of fghting ability in men.