Reflections on the Evolution of Morality Christine M. Korsgaard

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evolution and Ethics 2

It is still disputed, however, why moral behavior extends beyond a close circle of kin and reciprocal relationships: e.g., most people think stealing from anyone is wrong, not just stealing from family and friends. For moral behavior to evolve as we understand it today, there likely had to be selective pressures that pushed people to disregard their own 1000wordphilosophy.com/2018/10/11/evolution- interests in favor of their group’s interest.[3] Exactly and-ethics/ how morality extended beyond this close circle is debated, with many theories under consideration.[4] Evolution and Ethics 2. What Should We Do? Author: Michael Klenk Suppose our ability to understand and apply moral Category: Ethics, Philosophy of Science rules, as typically understood, can be explained by Word Count: 999 natural selection. Does evolution explain which rules We often follow what are considered basic moral we should follow?[5] rules: don’t steal, don’t lie, help others when we can. Some answer, “yes!” “Greed captures the essence of But why do we follow these rules, or any rules the evolutionary spirit,” says the fictional character understood as “moral rules”? Does evolution explain Gordon Gekko in the 1987 film Wall Street: “Greed why? If so, does evolution have implications for … is good. Greed is right.”[6] which rules we should follow, and whether we genuinely know this? Gekko’s claims about what is good and right and what we ought to be comes from what he thinks we This essay explores the relations between evolution naturally are: we are greedy, so we ought to be and morality, including evolution’s potential greedy. -

The Evolution of Animal Play, Emotions, and Social Morality: on Science, Theology, Spirituality, Personhood, and Love

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 12-2001 The Evolution of Animal Play, Emotions, and Social Morality: On Science, Theology, Spirituality, Personhood, and Love Marc Bekoff University of Colorado Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/acwp_sata Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Behavior and Ethology Commons, and the Comparative Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Bekoff, M. (2001). The evolution of animal play, emotions, and social morality: on science, theology, spirituality, personhood, and love. Zygon®, 36(4), 615-655. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Evolution of Animal Play, Emotions, and Social Morality: On Science, Theology, Spirituality, Personhood, and Love Marc Bekoff University of Colorado KEYWORDS animal emotions, animal play, biocentric anthropomorphism, critical anthropomorphism, personhood, social morality, spirituality ABSTRACT My essay first takes me into the arena in which science, spirituality, and theology meet. I comment on the enterprise of science and how scientists could well benefit from reciprocal interactions with theologians and religious leaders. Next, I discuss the evolution of social morality and the ways in which various aspects of social play behavior relate to the notion of “behaving fairly.” The contributions of spiritual and religious perspectives are important in our coming to a fuller understanding of the evolution of morality. I go on to discuss animal emotions, the concept of personhood, and how our special relationships with other animals, especially the companions with whom we share our homes, help us to define our place in nature, our humanness. -

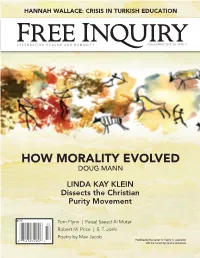

How Morality Evolved Doug Mann

HANNAH WALLACE: CRISIS IN TURKISH EDUCATION CELEBRATING REASON AND HUMANITY February/March 2019 Vol. 39 No. 2 HOW MORALITY EVOLVED DOUG MANN LINDA KAY KLEIN Dissects the Christian Purity Movement F/M 17 $5.95 CDN $5.95 US $5.95 Tom Flynn | Faisal Saeed Al Mutar 03 Robert M. Price | S. T. Joshi Poetry by Max Jacob Published by the Center for Inquiry in association 0 74470 74957 8 with the Council for Secular Humanism For many, mere atheism (the absence of belief in gods and the supernatural) or agnosticism (the view that such questions cannot be answered) aren’t enough. It’s liberating to recognize that supernatural beings are human creations … that there’s no such thing as “spirit” or “transcendence”… that people are undesigned, unintended, and responsible for themselves. But what’s next? Atheism and agnosticism are silent on larger questions of values and meaning. If Meaning in life is not ordained from on high, what small-m meanings can we work out among ourselves? If eternal life is an illusion, how can we make the most of our only lives? As social beings sharing a godless world, how should we coexist? For the questions that remain unanswered after we’ve cleared our minds of gods and souls and spirits, many atheists, agnostics, skeptics, and freethinkers turn to secular humanism. Secular. “Pertaining to the world or things not spiritual or sacred.” Humanism. “Any system of thought or action concerned with the interests or ideals of people … the intellectual and cultural movement … characterized by an emphasis on human interests rather than … religion.” — Webster’s Dictionary Secular humanism is a comprehensive, nonreligious life stance incorporating: A naturalistic philosophy A cosmic outlook rooted in science, and A consequentialist ethical system in which acts are judged not by their conformance to preselected norms but by their consequences for men and women in the world. -

Sexual Selection for Moral Virtues

Name /jlb_qrb822_3060012/820202/Mp_97 03/07/2007 04:48PM Plate # 0 pg 97 # 1 Volume 82, No. 2 THE QUARTERLY REVIEW OF BIOLOGY June 2007 SEXUAL SELECTION FOR MORAL VIRTUES Geoffrey F. Miller Psychology Department, University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131 USA e-mail: [email protected] keywords agreeableness, alternative mating strategies, altruism, assortative mating, behavior genetics, commitment, conscientiousness, costly signaling theory, equilibrium selection, emotion, empathy, ethics, evolutionary psychology, fitness indicators, genetic correlations, good genes, good parents, good partners, human courtship, kin selection, kindness, individual differences, intelligence, mate choice, mental health, moral virtues, mutation load, mutual choice, person perception, personality, reciprocal altruism, sexual fidelity, sexual selection, social cognition, virtue ethics “Human good turns out to be the activity of the soul exhibiting excellence.” Aristotle (350 BC) abstract Moral evolution theories have emphasized kinship, reciprocity, group selection, and equilibrium selection. Yet, moral virtues are also sexually attractive. Darwin suggested that sexual attractiveness may explain many aspects of human morality. This paper updates his argument by integrating recent research on mate choice, person perception, individual differences, costly signaling, and virtue ethics. Many human virtues may have evolved in both sexes through mutual mate choice to advertise good genetic quality, parenting abilities, and/or partner traits. Such virtues may include kindness, fidelity, magnanimity, and heroism, as well as quasi-moral traits like conscientiousness, agreeableness, mental health, and intelligence. This theory leads to many testable predictions about the phenotypic features, genetic bases, and social-cognitive responses to human moral virtues. Introduction tility, and longevity (Langlois et al. 2000; Fink MONG HUMANS, attractive bodies may and Penton-Voak 2002). -

Evolution of Morality Debate on Philosophy Forum, Mar 2004 This Discussion Eventually Wanders Into a Debate on Absolute Certainty

Evolution of Morality Debate on Philosophy Forum, Mar 2004 This discussion eventually wanders into a debate on absolute certainty. All quotations are in red. All responses to quotations by John Donovan unless otherwise noted. Quote: Originally Posted by Mariner I much prefer Dennett's "Darwin's Dangerous Idea" to Dawkins' "The Blind Watchmaker" by the way. Dawkins is too fond of hyperboles, and his arguments are often weak. Unlike Dennett's. I enjoy both authors immensely, though it is true that Dawkins sometimes writes in a somewhat pugalistic and shall we say, exuberant tone. But it makes for entertaining reading, for example have you read this very funny piece? http://www.physics.nyu.edu/faculty/sokal/dawkins.html In any case, both Dawkins and Dennett are clearly philosophical "soulmates". I can't imagine two men more in tune with each others ideas on so many issues. Just look at how Dennett has latched on to Dawkins' "memes" concept and applied it to his theory of consciousness. There is a discussion on this here for those interested in the link between language and the evolution of consciousness: http://forums.philosophyforums.com/...read.php?t=6031 Apologies in advance for the thread promotion. By Probeman (John Donovan) Quote: Originally Posted by jamespetts A characteristic, no doubt, with a strong genetic influence ;-) Seriously, I think there is something to this. Although I would say a strong "memetic" influence, instead. It makes sense to consider the idea that religious beliefs, such as the idea that we are the apple of God's eye, or the chosen people or that the universe was created just for us, etc., are all evolved memes that enhance human (social?) survival. -

The Biological Sciences Can Act As a Ground for Ethics” in Ayala, Francisco and Arp, Robert, Contemporary Debates in Philosophy of Biology

1 This chapter to be published as: Ruse, Michael (2009). “The Biological Sciences Can Act as a Ground for Ethics” in Ayala, Francisco and Arp, Robert, Contemporary Debates in Philosophy of Biology. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. The Biological Sciences Can Act as a Ground for Ethics Michael Ruse Ethics is an illusion put in place by natural selection to make us good cooperators. – Michael Ruse and Edward O. Wilson (1985) This paper is interested in the relationship between evolutionary thinking and moral behavior and commitments, ethics. There is a traditional way of forging or conceiving of the relationship. This is traditional evolutionary ethics, known as Social Darwinism. Many think that this position is morally pernicious, a re- description of the worst aspects of modern, laissez-faire capitalism in fancy biological language. It is argued that, in fact, there is much more to be said for Social Darwinism than many think. In respects, it could be and was an enlightened position to take; but it flounders on the matter of justification. Universally, the appeal is to progress—evolution is progressive and, hence, morally we should aid its success. I argue, however, that this progressive nature of evolution is far from obvious and, hence, traditional social Darwinism fails. There is another way to do things. This is to argue that the search for justification is mistaken. Ethics just is. It is an adaptation for humans living socially and has exactly the same status as other adaptations, like hands and teeth and genitalia. As such, ethics is something with no standing beyond what it is. -

The Evolved Functions of Procedural Fairness: an Adaptation for Politics

March 2015 The Evolved Functions of Procedural Fairness: An Adaptation for Politics Troels Bøggild Department of Political Science Aarhus University, Denmark E-mail: [email protected] Michael Bang Petersen Department of Political Science Aarhus University, Denmark E-mail: [email protected] Chapter accepted for publication in Todd K. Shackelford & Ranald D. Hansen (Eds.), The Evolution of Morality, New York: Springer. 1 Abstract: Politics is the process of determining resource allocations within and between groups. Group life has constituted a critical and enduring part of human evolutionary history and we should expect the human mind to contain psychological adaptations for dealing with political problems. Previous research has in particular focused on adaptations designed to produce moral evaluations of political outcomes: is the allocation of resources fair? People, however, are not only concerned about outcomes. They also readily produce moral evaluations of the political processes that shape these outcomes. People have a sense of procedural fairness. In this chapter, we identify the adaptive functions of the human psychology of procedural fairness. We argue that intuitions about procedural fairness evolved to deal with adaptive problems related to the delegation of leadership and, specifically, to identify and counter-act exploitative leaders. In the chapter, we first introduce the concept of procedural fairness, review extant social psychological theories and make the case for why an evolutionary approach is needed. Next, we dissect the evolved functions of procedural fairness and review extant research in favor of the evolutionary account. Finally, we discuss how environmental mismatches between ancestral and modern politics make procedural fairness considerations even more potent in modern politics, creating a powerful source of moral outrage. -

The Natures of Universal Moralities, 75 Brook

Brooklyn Law Review Volume 75 Issue 2 SYMPOSIUM: Article 4 Is Morality Universal, and Should the Law Care? 2009 The aN tures of Universal Moralities Bailey Kuklin Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr Recommended Citation Bailey Kuklin, The Natures of Universal Moralities, 75 Brook. L. Rev. (2009). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/blr/vol75/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Law Review by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. The Natures of Universal Moralities Bailey Kuklin† One of the abiding lessons from postmodernism is that reason does not go all the way down.1 In the context of this symposium, one cannot deductively derive a universal morality from incontestible moral primitives,2 or practical reason alone.3 Instead, even reasoned moral systems must ultimately be grounded on intuition,4 a sense of justice. The question then † Professor of Law, Brooklyn Law School. I wish to thank the presenters and participants of the Brooklyn Law School Symposium entitled “Is Morality Universal, and Should the Law Care?” and those at the Tenth SEAL Scholarship Conference. Further thanks go to Brooklyn Law School for supporting this project with a summer research stipend. 1 “Simplifying to the extreme, I define postmodern as incredulity toward metanarratives.” JEAN-FRANCOIS LYOTARD, THE POSTMODERN CONDITION: A REPORT ON KNOWLEDGE xxiv (Geoff Bennington & Brian Massumi trans., 1984). “If modernity is viewed with Weberian optimism as the project of rationalisation of the life-world, an era of material progress, social emancipation and scientific innovation, the postmodern is derided as chaotic, catastrophic, nihilistic, the end of good order.” COSTAS DOUZINAS ET AL., POSTMODERN JURISPRUDENCE 16 (1991). -

Lecture Two: the Evolution of Morality: the Emergence of Personhood

HTS Teologiese Studies/Theological Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-8050, (Print) 0259-9422 Page 1 of 11 Original Research Lecture two: The evolution of morality: The emergence of personhood Author: In a series of three articles, presented at the Goshen Annual Conference on Science and Religion 1,2 J. Wentzel van Huyssteen in 2015, with the theme ‘Interdisciplinary Theology and the Archeology of Personhood’, J. Affiliations: Wentzel van Huyssteen considers the problem of human evolution – also referred to as ‘the 1Princeton Theological archaeology of personhood’ – and its broader impact on theological anthropology. This Seminary, United States trajectory of lectures tracks a select number of challenging contemporary proposals for the evolution of crucially important aspects of human personhood. Lecture Two argues that, on a 2Faculty of Theology, postfoundationalist view, some of our religious beliefs are indeed more plausible and credible Stellenbosch University, South Africa than others. This also goes for our tendency to moralise and for the strong moral convictions, we often hold. It demonstrates that, in spite of a powerful focus on the evolutionary origins of Corresponding author: moral awareness, ethics emerge on a culturally autonomous level, which means that the J. Wentzel van Huyssteen, wentzel.vanhuyssteen@ epistemic standing of the particular moral judgements human beings make is independent of ptsem.edu whatever the natural sciences can says about their genesis. Dates: Received: 09 Dec. 2016 Accepted: 21 Aug. 2017 Introduction Published: 30 Nov. 2017 As we saw in the first lecture, it is the materiality of our embodied existence that has come about through the long process of biological evolution and has given us what seems to be a unique How to cite this article: Van Huyssteen, J.W., 2017, human sense of self. -

Moral Reputation: an Evolutionary and Cognitive Perspective

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Goldstone Research Unit Philosophy, Politics and Economics 10-29-2012 Moral Reputation: An Evolutionary and Cognitive Perspective Dan Sperber Nicolas Baumard Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/goldstone Part of the Cognitive Psychology Commons, Ethics and Political Philosophy Commons, and the Theory and Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Sperber, D., & Baumard, N. (2012). Moral Reputation: An Evolutionary and Cognitive Perspective. Mind & Language, 27 (5), 495-518. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/mila.12000 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/goldstone/8 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Moral Reputation: An Evolutionary and Cognitive Perspective Abstract From an evolutionary point of view, the function of moral behaviour may be to secure a good reputation as a co-operator. The best way to do so may be to obey genuine moral motivations. Still, one's moral reputation maybe something too important to be entrusted just to one's moral sense. A robust concern for one's reputation is likely to have evolved too. Here we explore some of the complex relationships between morality and reputation both from an evolutionary and a cognitive point of view. Disciplines Cognitive Psychology | Ethics and Political Philosophy | Theory and Philosophy This journal article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/goldstone/8 Moral reputation: An evolutionary and cognitive perspective* Dan SPERBER and Nicolas BAUMARD Abstract: From an evolutionary point of view, the function of moral behaviour may be to secure a good reputation as a co-operator. The best way to do so may be to obey genuine moral motivations. -

The Morality of Evolutionarily Self-Interested Rescues

Brooklyn Law School BrooklynWorks Faculty Scholarship 2006 The orM ality of Evolutionarily Self-Interested Rescues Bailey Kuklin Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/faculty Part of the Law and Philosophy Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation 40 Ariz. St. L. J. 453 (2008) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of BrooklynWorks. THE MORALITY OF EVOLUTIONARILY SELF- INTERESTED RESCUES Bailey Kuklint Introduction ................................................................................................ 453 I. The Rescue Doctrine and Evolutionary Psychology ............................ 456 A . "Peril Invites R escue" ................................................................... 456 B. Evolutionary Psychology ............................................................... 457 1. Kin Selection ............................................................................ 458 2. R eciprocal A ltruism ................................................................. 459 3. Sexual Selection ....................................................................... 466 C. Evolutionary Behavioral Maxims .................................................. 469 II. M orality of R escue ............................................................................... 473 A . U tilitarianism .................................................................................. 477 -

The Question of Non Human Primates Morality

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE Mateusz Stępień provided by Jagiellonian Univeristy Repository THE QUESTION OF NON HUMAN PRIMATES MORALITY He who understands baboons would do more toward metaphysics than Locke. Ch. Darwin, Notebook Introduction Walking in Darwin’s footsteps, numerous researchers have turned toward evolutionary theory for “the examination of a hypothesis concerning the factual matter of whether, and in what sense, and to what degree, human morality is the product of the process of biological natural selection.”1 The questions of morality have been partly taken over from the hands of philosophers and “biologized” as E.O. Wilson already recommended more than three decades ago.2 In spite of the fundamental disputes undertaken in general evolutionary theory, many specifi c empirical disciplines work on the adequate description and explication of partic- ular morality-related issues. Neuroscience tries to map the “moral brain,” mean- while by examining children in their earliest years, developmental psychology studies ontogenetic changes in the processes of moral reasoning and the emer- gence of the distinction between moral and other norms. Moral psychology stud- ies universal cognitive and emotional psychological mechanisms related with morality (e.g. moral judgments, moral dilemmas) and “universal across cultures moral domains.” Recently, primatology has also contributed to the “biologizing of morality” enterprise, mainly by searching for and examining “proto-morality” or “the evolutionary building blocks of morality” in non human primates (hereafter termed NHP). The primatological studies are a part of the emerging literature on the “animal morality” question,3 but without a doubt research on NHP cur- 1 R.