Moral Reputation: an Evolutionary and Cognitive Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modularity As a Concept Modern Ideas About Mental Modularity Typically Use Fodor (1983) As a Key Touchstone

COGNITIVE PROCESSING International Quarterly of Cognitive Science Mental modularity, metaphors, and the marriage of evolutionary and cognitive sciences GARY L. BRASE University of Missouri – Columbia Abstract - As evolutionary approaches in the behavioral sciences become increasingly prominent, issues arising from the proposition that the mind is a collection of modular adaptations (the multi-modular mind thesis) become even more pressing. One purpose of this paper is to help clarify some valid issues raised by this thesis and clarify why other issues are not as critical. An aspect of the cognitive sciences that appears to both promote and impair progress on this issue (in different ways) is the use of metaphors for understand- ing the mind. Utilizing different metaphors can yield different perspectives and advancement in our understanding of the nature of the human mind. A second purpose of this paper is to outline the kindred natures of cognitive science and evolutionary psychology, both of which cut across traditional academic divisions and engage in functional analyses of problems. Key words: Evolutionary Theory, Cognitive Science, Modularity, Metaphors Evolutionary approaches in the behavioral sciences have begun to influence a wide range of fields, from cognitive neuroscience (e.g., Gazzaniga, 1998), to clini- cal psychology (e.g., Baron-Cohen, 1997; McGuire and Troisi, 1998), to literary theory (e.g., Carroll, 1999). At the same time, however, there are ongoing debates about the details of what exactly an evolutionary approach – often called evolu- tionary psychology— entails (Holcomb, 2001). Some of these debates are based on confusions of terminology, implicit arguments, or misunderstandings – things that can in principle be resolved by clarifying current ideas. -

Beowulf and Competitive Altruism,” P

January 2013 Volume 9, Issue 1 ASEBL Journal Association for the Study of Editor (Ethical Behavior)•(Evolutionary Biology) in Literature St. Francis College, Brooklyn Heights, N.Y. Gregory F. Tague, Ph.D. ~ Editorial Board ~▪▪~ Kristy Biolsi, Ph.D. THIS ISSUE FEATURES Kevin Brown, Ph.D. Wendy Galgan, Ph.D. † Eric Luttrell, “Modest Heroism: Beowulf and Competitive Altruism,” p. 2 Cheryl L. Jaworski, M.A. † Dena R. Marks, “Secretary of Disorientation: Writing the Circularity of Belief in Elizabeth Costello,” p.11 Anja Müller-Wood, Ph.D. Kathleen A. Nolan, Ph.D. † Margaret Bertucci Hamper, “’The poor little working girl’: The New Woman, Chloral, and Motherhood in The House of Mirth,” p. 19 Riza Öztürk, Ph.D. † Kristin Mathis, “Moral Courage in The Runaway Jury,” p. 22 Eric Platt, Ph.D. † William Bamberger, “A Labyrinthine Modesty: On Raymond Roussel Michelle Scalise Sugiyama, and Chiasmus,” p. 24 Ph.D. ~▪~ Editorial Interns † St. Francis College Moral Sense Colloquium: - Program Notes, p. 27 Tyler Perkins - Kristy L. Biolsi, “What Does it Mean to be a Moral Animal?”, p. 29 - Sophie Berman, “Science sans conscience n’est que ruine de l’âme,” p.36 ~▪~ Kimberly Resnick † Book Reviews: - Lisa Zunshine, editor, Introduction to Cognitive Cultural Studies. Gregory F. Tague, p. 40 - Edward O. Wilson, The Social Conquest of Earth. Wendy Galgan, p. 42 ~▪~ ~ Contributor Notes, p. 45 Announcements, p. 45 ASEBL Journal Copyright©2013 E-ISSN: 1944-401X *~* [email protected] www.asebl.blogspot.com ASEBL Journal – Volume 9 Issue 1, January 2013 Modest Heroism: Beowulf and Competitive Altruism Eric Luttrell Christian Virtues or Human Virtues? Over the past decade, adaptations of Beowulf in popular media have portrayed the eponymous hero as a dim-witted and egotistical hot-head. -

Reflections on the Evolution of Morality Christine M. Korsgaard

Reflections on the Evolution of Morality Christine M. Korsgaard Harvard University1 All instincts that do not discharge themselves outwardly turn inward – this is what I call the internalization of man: thus it was that man first developed what was later called his “soul.” The entire inner world, originally as thin as if it were stretched between two membranes, expanded and extended itself, acquiring depth, breadth, and height, in the same measure as outward discharge was inhibited. - Nietzsche 1. Introduction In recent years there has been a fair amount of speculation about the evolution of morality, among scientists and philosophers alike. From both points of view, the question how our moral nature might have evolved is interesting because morality is one of the traditional candidates for a distinctively human attribute, something that makes us different from the other animals. From a scientific point of view, it matters whether there are any such attributes because of the special burden they seem to place on the theory of evolution. Beginning with Darwin’s own efforts in The Descent of Man, defenders of the theory of evolution have tried to show either that there are no genuinely distinctive human attributes – that is, that any differences between human beings and the other animals are a matter of degree – or that apparently distinctive human attributes can be explained in terms of the 1 Notes on this version are incomplete. Recommended supplemental reading: “The Activity of Reason,” APA Proceedings November 09, pp. 30-38. In a way, these papers are companion pieces, or at least their final sections are. -

In Defense of Massive Modularity

3 In Defense of Massive Modularity Dan Sperber In October 1990, a psychologist, Susan Gelman, and three anthropolo- gists whose interest in cognition had been guided and encouraged by Jacques Mehler, Scott Atran, Larry Hirschfeld, and myself, organized a conference on “Cultural Knowledge and Domain Specificity” (see Hirsch- feld and Gelman, 1994). Jacques advised us in the preparation of the conference, and while we failed to convince him to write a paper, he did play a major role in the discussions. A main issue at stake was the degree to which cognitive development, everyday cognition, and cultural knowledge are based on dedicated do- main-specific mechanisms, as opposed to a domain-general intelligence and learning capacity. Thanks in particular to the work of developmental psychologists such as Susan Carey, Rochel Gelman, Susan Gelman, Frank Keil, Alan Leslie, Jacques Mehler, Elizabeth Spelke (who were all there), the issue of domain-specificity—which, of course, Noam Chomsky had been the first to raise—was becoming a central one in cognitive psychol- ogy. Evolutionary psychology, represented at the conference by Leda Cosmides and John Tooby, was putting forward new arguments for seeing human cognition as involving mostly domain- or task-specific evolved adaptations. We were a few anthropologists, far from the main- stream of our discipline, who also saw domain-specific cognitive pro- cesses as both constraining and contributing to cultural development. Taking for granted that domain-specific dispositions are an important feature of human cognition, three questions arise: 1. To what extent are these domain-specific dispositions based on truly autonomous mental mechanisms or “modules,” as opposed to being 48 D. -

Evolution and Ethics 2

It is still disputed, however, why moral behavior extends beyond a close circle of kin and reciprocal relationships: e.g., most people think stealing from anyone is wrong, not just stealing from family and friends. For moral behavior to evolve as we understand it today, there likely had to be selective pressures that pushed people to disregard their own 1000wordphilosophy.com/2018/10/11/evolution- interests in favor of their group’s interest.[3] Exactly and-ethics/ how morality extended beyond this close circle is debated, with many theories under consideration.[4] Evolution and Ethics 2. What Should We Do? Author: Michael Klenk Suppose our ability to understand and apply moral Category: Ethics, Philosophy of Science rules, as typically understood, can be explained by Word Count: 999 natural selection. Does evolution explain which rules We often follow what are considered basic moral we should follow?[5] rules: don’t steal, don’t lie, help others when we can. Some answer, “yes!” “Greed captures the essence of But why do we follow these rules, or any rules the evolutionary spirit,” says the fictional character understood as “moral rules”? Does evolution explain Gordon Gekko in the 1987 film Wall Street: “Greed why? If so, does evolution have implications for … is good. Greed is right.”[6] which rules we should follow, and whether we genuinely know this? Gekko’s claims about what is good and right and what we ought to be comes from what he thinks we This essay explores the relations between evolution naturally are: we are greedy, so we ought to be and morality, including evolution’s potential greedy. -

Review of Sperber & Wilson 1986. Relevance: Communication And

Review of Sperber & Wilson 1986. Relevance : Communication and Cognition Daniel Hirst To cite this version: Daniel Hirst. Review of Sperber & Wilson 1986. Relevance : Communication and Cognition. Mind and Language, Wiley, 1989, 4 (1/2), pp.138-146. hal-02552695 HAL Id: hal-02552695 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02552695 Submitted on 23 Apr 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Review of Dan Sperber and Deirdre Wilson (1986) Relevance : Communication and Cognition. (Blackwell's, Oxford) Daniel Hirst - CNRS Parole et Langage, Université de Provence. One of the examples Sperber & Wilson ask us to consider is the sentence : "It took us a long time to write this book" (p 122) In case the reader misses the point, they explain in the preface that the book developped out of a project begun over ten years ago to write "in a few months" a joint essay on semantics, pragmatics and rhetoric. The resulting book has been long awaited, having been announced as "forthcoming" since at least 1979 under various provisional titles ranging from The Interpretation of Utterances : Semantics, Pragmatics & Rhetoric (Wilson & Sperber 1979) through Foundations of Pragmatic Theory (Wilson & Sperber 1981) to Language and Relevance (Wilson & Sperber 1985). -

Altruism, Morality & Social Solidarity Forum

Altruism, Morality & Social Solidarity Forum A Forum for Scholarship and Newsletter of the AMSS Section of ASA Volume 3, Issue 2 May 2012 What’s so Darned Special about Church Friends? Robert D. Putnam Harvard University One purpose of my recent research (with David E. Campbell) on religion in America1 was to con- firm and, if possible, extend previous research on the correlation of religiosity and altruistic behavior, such as giving, volunteering, and community involvement. It proved straight-forward to show that each of sev- eral dozen measures of good neighborliness was strongly correlated with religious involvement. Continued on page 19... Our Future is Just Beginning Vincent Jeffries, Acting Chairperson California State University, Northridge The beginning of our endeavors has ended. The study of altruism, morality, and social solidarity is now an established section in the American Sociological Association. We will have our first Section Sessions at the 2012 American Sociological Association Meetings in Denver, Colorado, this August. There is a full slate of candidates for the ASA elections this spring, and those chosen will take office at the Meetings. Continued on page 4... The Revival of Russian Sociology and Studies of This Issue: Social Solidarity From the Editor 2 Dmitry Efremenko and Yaroslava Evseeva AMSS Awards 3 Institute of Scientific Information for Social Sciences, Russian Academy of Sciences Scholarly Updates 12 The article was executed in the framework of the research project Social solidarity as a condition of society transformations: Theoretical foundations, Bezila 16 Russian specificity, socio-biological and socio-psychological aspects, supported Dissertation by the Russian foundation for basic research (Project 11-06-00347а). -

Past and Present Environments

Journal of Evolutionary Psychology, 2011, 275-278 DOI: 10.1556/JEP.9.2011.3.5 PAST AND PRESENT ENVIRONMENTS A review of Decision Making: Towards an Evolutionary Psychology of Rationality, by Mauro Maldonato. Sussex Academic Press (2010), 121 pages, $32.50. ISBN: 978-1-84519-421-5 (paperback) 1 2 CHELSEA ROSS AND ANDREAS WILKE Department of Psychology, Clarkson University In his book, Maldonato provides a thoughtful look at how early scholars viewed de- cision-making and rationality. He takes the reader on an illustrative journey through the historic passages of decision-making all the way to modern notions of a more limited rationality and how humans can make choices under risk and uncertainty. He discusses Kahneman and Tversky’s seminal work on heuristics and biases— “short cuts” that rely on little information and modest cognitive resources that sometimes lead to persistent failures, but usually allow the decision-maker to make fast and fairly reliable choices. Herbert Simon and Gerd Gigerenzer’s work on bounded rationality is discussed, with respect to its influence on decision-making research in economics and psychology. For Maldonato, the principle of bounded ra- tionality—that organisms have limited resources, such as time, information, and cognitive capacity with which to find solutions to the problems they face—is a key insight to understanding the evolution of decision-making. Maldonato proposes that evolutionary pressures urged the human mind to adopt a primitive decision-making process. For the purpose of survival, the majority of human choices had to be made by means of simple and fast decision strategies, because the decision-making system developed under general human cognitive limitations and from environmental pressures that selected for decision strategies suited for the harsh ancestral living environments as well as the resources at hand. -

The Evolution of Animal Play, Emotions, and Social Morality: on Science, Theology, Spirituality, Personhood, and Love

WellBeing International WBI Studies Repository 12-2001 The Evolution of Animal Play, Emotions, and Social Morality: On Science, Theology, Spirituality, Personhood, and Love Marc Bekoff University of Colorado Follow this and additional works at: https://www.wellbeingintlstudiesrepository.org/acwp_sata Part of the Animal Studies Commons, Behavior and Ethology Commons, and the Comparative Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Bekoff, M. (2001). The evolution of animal play, emotions, and social morality: on science, theology, spirituality, personhood, and love. Zygon®, 36(4), 615-655. This material is brought to you for free and open access by WellBeing International. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of the WBI Studies Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Evolution of Animal Play, Emotions, and Social Morality: On Science, Theology, Spirituality, Personhood, and Love Marc Bekoff University of Colorado KEYWORDS animal emotions, animal play, biocentric anthropomorphism, critical anthropomorphism, personhood, social morality, spirituality ABSTRACT My essay first takes me into the arena in which science, spirituality, and theology meet. I comment on the enterprise of science and how scientists could well benefit from reciprocal interactions with theologians and religious leaders. Next, I discuss the evolution of social morality and the ways in which various aspects of social play behavior relate to the notion of “behaving fairly.” The contributions of spiritual and religious perspectives are important in our coming to a fuller understanding of the evolution of morality. I go on to discuss animal emotions, the concept of personhood, and how our special relationships with other animals, especially the companions with whom we share our homes, help us to define our place in nature, our humanness. -

Information Systems Theorizing Based on Evolutionary Psychology: an Interdisciplinary Review and Theory Integration Framework1

Kock/IS Theorizing Based on Evolutionary Psychology THEORY AND REVIEW INFORMATION SYSTEMS THEORIZING BASED ON EVOLUTIONARY PSYCHOLOGY: AN INTERDISCIPLINARY REVIEW AND THEORY INTEGRATION FRAMEWORK1 By: Ned Kock on one evolutionary information systems theory—media Division of International Business and Technology naturalness theory—previously developed as an alternative to Studies media richness theory, and one non-evolutionary information Texas A&M International University systems theory, channel expansion theory. 5201 University Boulevard Laredo, TX 78041 Keywords: Information systems, evolutionary psychology, U.S.A. theory development, media richness theory, media naturalness [email protected] theory, channel expansion theory Abstract Introduction Evolutionary psychology holds great promise as one of the possible pillars on which information systems theorizing can While information systems as a distinct area of research has take place. Arguably, evolutionary psychology can provide the potential to be a reference for other disciplines, it is the key to many counterintuitive predictions of behavior reasonable to argue that information systems theorizing can toward technology, because many of the evolved instincts that benefit from fresh new insights from other fields of inquiry, influence our behavior are below our level of conscious which may in turn enhance even more the reference potential awareness; often those instincts lead to behavioral responses of information systems (Baskerville and Myers 2002). After that are not self-evident. This paper provides a discussion of all, to be influential in other disciplines, information systems information systems theorizing based on evolutionary psych- research should address problems that are perceived as rele- ology, centered on key human evolution and evolutionary vant by scholars in those disciplines and in ways that are genetics concepts and notions. -

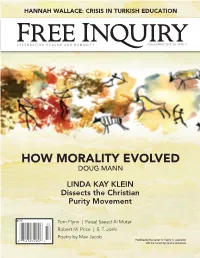

How Morality Evolved Doug Mann

HANNAH WALLACE: CRISIS IN TURKISH EDUCATION CELEBRATING REASON AND HUMANITY February/March 2019 Vol. 39 No. 2 HOW MORALITY EVOLVED DOUG MANN LINDA KAY KLEIN Dissects the Christian Purity Movement F/M 17 $5.95 CDN $5.95 US $5.95 Tom Flynn | Faisal Saeed Al Mutar 03 Robert M. Price | S. T. Joshi Poetry by Max Jacob Published by the Center for Inquiry in association 0 74470 74957 8 with the Council for Secular Humanism For many, mere atheism (the absence of belief in gods and the supernatural) or agnosticism (the view that such questions cannot be answered) aren’t enough. It’s liberating to recognize that supernatural beings are human creations … that there’s no such thing as “spirit” or “transcendence”… that people are undesigned, unintended, and responsible for themselves. But what’s next? Atheism and agnosticism are silent on larger questions of values and meaning. If Meaning in life is not ordained from on high, what small-m meanings can we work out among ourselves? If eternal life is an illusion, how can we make the most of our only lives? As social beings sharing a godless world, how should we coexist? For the questions that remain unanswered after we’ve cleared our minds of gods and souls and spirits, many atheists, agnostics, skeptics, and freethinkers turn to secular humanism. Secular. “Pertaining to the world or things not spiritual or sacred.” Humanism. “Any system of thought or action concerned with the interests or ideals of people … the intellectual and cultural movement … characterized by an emphasis on human interests rather than … religion.” — Webster’s Dictionary Secular humanism is a comprehensive, nonreligious life stance incorporating: A naturalistic philosophy A cosmic outlook rooted in science, and A consequentialist ethical system in which acts are judged not by their conformance to preselected norms but by their consequences for men and women in the world. -

Sexual Selection for Moral Virtues

Name /jlb_qrb822_3060012/820202/Mp_97 03/07/2007 04:48PM Plate # 0 pg 97 # 1 Volume 82, No. 2 THE QUARTERLY REVIEW OF BIOLOGY June 2007 SEXUAL SELECTION FOR MORAL VIRTUES Geoffrey F. Miller Psychology Department, University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico 87131 USA e-mail: [email protected] keywords agreeableness, alternative mating strategies, altruism, assortative mating, behavior genetics, commitment, conscientiousness, costly signaling theory, equilibrium selection, emotion, empathy, ethics, evolutionary psychology, fitness indicators, genetic correlations, good genes, good parents, good partners, human courtship, kin selection, kindness, individual differences, intelligence, mate choice, mental health, moral virtues, mutation load, mutual choice, person perception, personality, reciprocal altruism, sexual fidelity, sexual selection, social cognition, virtue ethics “Human good turns out to be the activity of the soul exhibiting excellence.” Aristotle (350 BC) abstract Moral evolution theories have emphasized kinship, reciprocity, group selection, and equilibrium selection. Yet, moral virtues are also sexually attractive. Darwin suggested that sexual attractiveness may explain many aspects of human morality. This paper updates his argument by integrating recent research on mate choice, person perception, individual differences, costly signaling, and virtue ethics. Many human virtues may have evolved in both sexes through mutual mate choice to advertise good genetic quality, parenting abilities, and/or partner traits. Such virtues may include kindness, fidelity, magnanimity, and heroism, as well as quasi-moral traits like conscientiousness, agreeableness, mental health, and intelligence. This theory leads to many testable predictions about the phenotypic features, genetic bases, and social-cognitive responses to human moral virtues. Introduction tility, and longevity (Langlois et al. 2000; Fink MONG HUMANS, attractive bodies may and Penton-Voak 2002).