Book Rev of Ideas That Created the Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Efficient Algorithms with Asymmetric Read and Write Costs

Efficient Algorithms with Asymmetric Read and Write Costs Guy E. Blelloch1, Jeremy T. Fineman2, Phillip B. Gibbons1, Yan Gu1, and Julian Shun3 1 Carnegie Mellon University 2 Georgetown University 3 University of California, Berkeley Abstract In several emerging technologies for computer memory (main memory), the cost of reading is significantly cheaper than the cost of writing. Such asymmetry in memory costs poses a fun- damentally different model from the RAM for algorithm design. In this paper we study lower and upper bounds for various problems under such asymmetric read and write costs. We con- sider both the case in which all but O(1) memory has asymmetric cost, and the case of a small cache of symmetric memory. We model both cases using the (M, ω)-ARAM, in which there is a small (symmetric) memory of size M and a large unbounded (asymmetric) memory, both random access, and where reading from the large memory has unit cost, but writing has cost ω 1. For FFT and sorting networks we show a lower bound cost of Ω(ωn logωM n), which indicates that it is not possible to achieve asymptotic improvements with cheaper reads when ω is bounded by a polynomial in M. Moreover, there is an asymptotic gap (of min(ω, log n)/ log(ωM)) between the cost of sorting networks and comparison sorting in the model. This contrasts with the RAM, and most other models, in which the asymptotic costs are the same. We also show a lower bound for computations on an n × n diamond DAG of Ω(ωn2/M) cost, which indicates no asymptotic improvement is achievable with fast reads. -

Butler Lampson, Martin Abadi, Michael Burrows, Edward Wobber

Outline • Chapter 19: Security (cont) • A Method for Obtaining Digital Signatures and Public-Key Cryptosystems Ronald L. Rivest, Adi Shamir, and Leonard M. Adleman. Communications of the ACM 21,2 (Feb. 1978) – RSA Algorithm – First practical public key crypto system • Authentication in Distributed Systems: Theory and Practice, Butler Lampson, Martin Abadi, Michael Burrows, Edward Wobber – Butler Lampson (MSR) - He was one of the designers of the SDS 940 time-sharing system, the Alto personal distributed computing system, the Xerox 9700 laser printer, two-phase commit protocols, the Autonet LAN, and several programming languages – Martin Abadi (Bell Labs) – Michael Burrows, Edward Wobber (DEC/Compaq/HP SRC) Oct-21-03 CSE 542: Operating Systems 1 Encryption • Properties of good encryption technique: – Relatively simple for authorized users to encrypt and decrypt data. – Encryption scheme depends not on the secrecy of the algorithm but on a parameter of the algorithm called the encryption key. – Extremely difficult for an intruder to determine the encryption key. Oct-21-03 CSE 542: Operating Systems 2 Strength • Strength of crypto system depends on the strengths of the keys • Computers get faster – keys have to become harder to keep up • If it takes more effort to break a code than is worth, it is okay – Transferring money from my bank to my credit card and Citibank transferring billions of dollars with another bank should not have the same key strength Oct-21-03 CSE 542: Operating Systems 3 Encryption methods • Symmetric cryptography – Sender and receiver know the secret key (apriori ) • Fast encryption, but key exchange should happen outside the system • Asymmetric cryptography – Each person maintains two keys, public and private • M ≡ PrivateKey(PublicKey(M)) • M ≡ PublicKey (PrivateKey(M)) – Public part is available to anyone, private part is only known to the sender – E.g. -

Great Ideas in Computing

Great Ideas in Computing University of Toronto CSC196 Winter/Spring 2019 Week 6: October 19-23 (2020) 1 / 17 Announcements I added one final question to Assignment 2. It concerns search engines. The question may need a little clarification. I have also clarified question 1 where I have defined (in a non standard way) the meaning of a strict binary search tree which is what I had in mind. Please answer the question for a strict binary search tree. If you answered the quiz question for a non strict binary search tree withn a proper explanation you will get full credit. Quick poll: how many students feel that Q1 was a fair quiz? A1 has now been graded by Marta. I will scan over the assignments and hope to release the grades later today. If you plan to make a regrading request, you have up to one week to submit your request. You must specify clearly why you feel that a question may not have been graded fairly. In general, students did well which is what I expected. 2 / 17 Agenda for the week We will continue to discuss search engines. We ended on what is slide 10 (in Week 5) on Friday and we will continue with where we left off. I was surprised that in our poll, most students felt that the people advocating the \AI view" of search \won the debate" whereas today I will try to argue that the people (e.g., Salton and others) advocating the \combinatorial, algebraic, statistical view" won the debate as to current search engines. -

Edsger Dijkstra: the Man Who Carried Computer Science on His Shoulders

INFERENCE / Vol. 5, No. 3 Edsger Dijkstra The Man Who Carried Computer Science on His Shoulders Krzysztof Apt s it turned out, the train I had taken from dsger dijkstra was born in Rotterdam in 1930. Nijmegen to Eindhoven arrived late. To make He described his father, at one time the president matters worse, I was then unable to find the right of the Dutch Chemical Society, as “an excellent Aoffice in the university building. When I eventually arrived Echemist,” and his mother as “a brilliant mathematician for my appointment, I was more than half an hour behind who had no job.”1 In 1948, Dijkstra achieved remarkable schedule. The professor completely ignored my profuse results when he completed secondary school at the famous apologies and proceeded to take a full hour for the meet- Erasmiaans Gymnasium in Rotterdam. His school diploma ing. It was the first time I met Edsger Wybe Dijkstra. shows that he earned the highest possible grade in no less At the time of our meeting in 1975, Dijkstra was 45 than six out of thirteen subjects. He then enrolled at the years old. The most prestigious award in computer sci- University of Leiden to study physics. ence, the ACM Turing Award, had been conferred on In September 1951, Dijkstra’s father suggested he attend him three years earlier. Almost twenty years his junior, I a three-week course on programming in Cambridge. It knew very little about the field—I had only learned what turned out to be an idea with far-reaching consequences. a flowchart was a couple of weeks earlier. -

Early Stored Program Computers

Stored Program Computers Thomas J. Bergin Computing History Museum American University 7/9/2012 1 Early Thoughts about Stored Programming • January 1944 Moore School team thinks of better ways to do things; leverages delay line memories from War research • September 1944 John von Neumann visits project – Goldstine’s meeting at Aberdeen Train Station • October 1944 Army extends the ENIAC contract research on EDVAC stored-program concept • Spring 1945 ENIAC working well • June 1945 First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC 7/9/2012 2 First Draft Report (June 1945) • John von Neumann prepares (?) a report on the EDVAC which identifies how the machine could be programmed (unfinished very rough draft) – academic: publish for the good of science – engineers: patents, patents, patents • von Neumann never repudiates the myth that he wrote it; most members of the ENIAC team contribute ideas; Goldstine note about “bashing” summer7/9/2012 letters together 3 • 1.0 Definitions – The considerations which follow deal with the structure of a very high speed automatic digital computing system, and in particular with its logical control…. – The instructions which govern this operation must be given to the device in absolutely exhaustive detail. They include all numerical information which is required to solve the problem…. – Once these instructions are given to the device, it must be be able to carry them out completely and without any need for further intelligent human intervention…. • 2.0 Main Subdivision of the System – First: since the device is a computor, it will have to perform the elementary operations of arithmetics…. – Second: the logical control of the device is the proper sequencing of its operations (by…a control organ. -

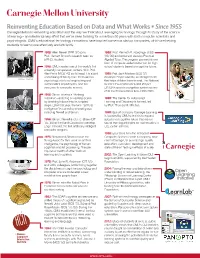

Reinventing Education Based on Data and What Works • Since 1955

Reinventing Education Based on Data and What Works • Since 1955 Carnegie Mellon is reinventing education and the way we think about leveraging technology through its study of the science of learning – an interdisciplinary effort that we’ve been tackling for more than 50 years with both computer scientists and psychologists. CMU's educational technology innovations have inspired numerous startup companies, which are helping students to learn more effectively and efficiently. 1955: Allen Newell (TPR ’57) joins 1995: Prof. Kenneth R. Koedinger (HSS Prof. Herbert Simon’s research team as ’88,’90) and Anderson develop Practical a Ph.D. student. Algebra Tutor. The program pioneers a new form of computer-aided instruction for high 1956: CMU creates one of the world’s first school students based on cognitive tutors. university computation centers. With Prof. Alan Perlis (MCS ’42) as its head, it is a joint 1995: Prof. Jack Mostow (SCS ’81) undertaking of faculty from the business, develops Project LISTEN, an intelligent tutor Simon, Newell psychology, electrical engineering and that helps children learn to read. The National mathematics departments, and the Science Foundation included Project precursor to computer science. LISTEN’s speech recognition system as one of its top 50 innovations from 1950-2000. 1956: Simon creates a “thinking machine”—enacting a mental process 1995: The Center for Automated by breaking it down into its simplest Learning and Discovery is formed, led steps. Later that year, the term “artificial by Prof. Thomas M. Mitchell. intelligence” is coined by a small group Perlis including Newell and Simon. 1998: Spinoff company Carnegie Learning is founded by CMU scientists to expand 1956: Simon, Newell and J. -

Rivest, Shamir, and Adleman Receive 2002 Turing Award, Volume 50

Rivest, Shamir, and Adleman Receive 2002 Turing Award Cryptography and Information Se- curity Group. He received a B.A. in mathematics from Yale University and a Ph.D. in computer science from Stanford University. Shamir is the Borman Profes- sor in the Applied Mathematics Department of the Weizmann In- stitute of Science in Israel. He re- Ronald L. Rivest Adi Shamir Leonard M. Adleman ceived a B.S. in mathematics from Tel Aviv University and a Ph.D. in The Association for Computing Machinery (ACM) has computer science from the Weizmann Institute. named RONALD L. RIVEST, ADI SHAMIR, and LEONARD M. Adleman is the Distinguished Henry Salvatori ADLEMAN as winners of the 2002 A. M. Turing Award, Professor of Computer Science and Professor of considered the “Nobel Prize of Computing”, for Molecular Biology at the University of Southern their contributions to public key cryptography. California. He earned a B.S. in mathematics at the The Turing Award carries a $100,000 prize, with University of California, Berkeley, and a Ph.D. in funding provided by Intel Corporation. computer science, also at Berkeley. As researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of The ACM presented the Turing Award on June 7, Technology in 1977, the team developed the RSA 2003, in conjunction with the Federated Computing code, which has become the foundation for an en- Research Conference in San Diego, California. The tire generation of technology security products. It award was named for Alan M. Turing, the British mathematician who articulated the mathematical has also inspired important work in both theoret- foundation and limits of computing and who was a ical computer science and mathematics. -

The Advent of Recursion & Logic in Computer Science

The Advent of Recursion & Logic in Computer Science MSc Thesis (Afstudeerscriptie) written by Karel Van Oudheusden –alias Edgar G. Daylight (born October 21st, 1977 in Antwerpen, Belgium) under the supervision of Dr Gerard Alberts, and submitted to the Board of Examiners in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MSc in Logic at the Universiteit van Amsterdam. Date of the public defense: Members of the Thesis Committee: November 17, 2009 Dr Gerard Alberts Prof Dr Krzysztof Apt Prof Dr Dick de Jongh Prof Dr Benedikt Löwe Dr Elizabeth de Mol Dr Leen Torenvliet 1 “We are reaching the stage of development where each new gener- ation of participants is unaware both of their overall technological ancestry and the history of the development of their speciality, and have no past to build upon.” J.A.N. Lee in 1996 [73, p.54] “To many of our colleagues, history is only the study of an irrele- vant past, with no redeeming modern value –a subject without useful scholarship.” J.A.N. Lee [73, p.55] “[E]ven when we can't know the answers, it is important to see the questions. They too form part of our understanding. If you cannot answer them now, you can alert future historians to them.” M.S. Mahoney [76, p.832] “Only do what only you can do.” E.W. Dijkstra [103, p.9] 2 Abstract The history of computer science can be viewed from a number of disciplinary perspectives, ranging from electrical engineering to linguistics. As stressed by the historian Michael Mahoney, different `communities of computing' had their own views towards what could be accomplished with a programmable comput- ing machine. -

Efficient Algorithms with Asymmetric Read and Write Costs

Efficient Algorithms with Asymmetric Read and Write Costs Guy E. Blelloch1, Jeremy T. Fineman2, Phillip B. Gibbons1, Yan Gu1, and Julian Shun3 1 Carnegie Mellon University 2 Georgetown University 3 University of California, Berkeley Abstract In several emerging technologies for computer memory (main memory), the cost of reading is significantly cheaper than the cost of writing. Such asymmetry in memory costs poses a fun- damentally different model from the RAM for algorithm design. In this paper we study lower and upper bounds for various problems under such asymmetric read and write costs. We con- sider both the case in which all but O(1) memory has asymmetric cost, and the case of a small cache of symmetric memory. We model both cases using the (M, ω)-ARAM, in which there is a small (symmetric) memory of size M and a large unbounded (asymmetric) memory, both random access, and where reading from the large memory has unit cost, but writing has cost ω 1. For FFT and sorting networks we show a lower bound cost of Ω(ωn logωM n), which indicates that it is not possible to achieve asymptotic improvements with cheaper reads when ω is bounded by a polynomial in M. Moreover, there is an asymptotic gap (of min(ω, log n)/ log(ωM)) between the cost of sorting networks and comparison sorting in the model. This contrasts with the RAM, and most other models, in which the asymptotic costs are the same. We also show a lower bound for computations on an n × n diamond DAG of Ω(ωn2/M) cost, which indicates no asymptotic improvement is achievable with fast reads. -

Alan M. Turing – Simplification in Intelligent Computing Theory and Algorithms”

“Alan Turing Centenary Year - India Celebrations” 3-Day Faculty Development Program on “Alan M. Turing – Simplification in Intelligent Computing Theory and Algorithms” Organized by Foundation for Advancement of Education and Research In association with Computer Society of India - Division II [Software] NASSCOM, IFIP TC - 1 & TC -2, ACM India Council Co-sponsored by P.E.S Institute of Technology Venue PES Institute of Technology, Hoskerehalli, Bangalore Date : 18 - 20 December 2012 Compiled by : Prof. K. Rajanikanth Trustee, FAER “Alan Turing Centenary Year - India Celebrations” 3-Day Faculty Development Program on “Alan M. Turing – Simplification in Intelligent Computing Theory and Algorithms” Organized by Foundation for Advancement of Education and Research In association with Computer Society of India - Division II [Software], NASSCOM, IFIP TC - 1 & TC -2, ACM India Council Co-sponsored by P.E.S Institute of Technology December 18 – 20, 2012 Compiled by : Prof. K. Rajanikanth Trustee, FAER Foundation for Advancement of Education and Research G5, Swiss Complex, 33, Race Course Road, Bangalore - 560001 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.faer.ac.in PREFACE Alan Mathison Turing was born on June 23rd 1912 in Paddington, London. Alan Turing was a brilliant original thinker. He made original and lasting contributions to several fields, from theoretical computer science to artificial intelligence, cryptography, biology, philosophy etc. He is generally considered as the father of theoretical computer science and artificial intelligence. His brilliant career came to a tragic and untimely end in June 1954. In 1945 Turing was awarded the O.B.E. for his vital contribution to the war effort. In 1951 Turing was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society. -

SIGOPS Annual Report 2012

SIGOPS Annual Report 2012 Fiscal Year July 2012-June 2013 Submitted by Jeanna Matthews, SIGOPS Chair Overview SIGOPS is a vibrant community of people with interests in “operatinG systems” in the broadest sense, includinG topics such as distributed computing, storaGe systems, security, concurrency, middleware, mobility, virtualization, networkinG, cloud computinG, datacenter software, and Internet services. We sponsor a number of top conferences, provide travel Grants to students, present yearly awards, disseminate information to members electronically, and collaborate with other SIGs on important programs for computing professionals. Officers It was the second year for officers: Jeanna Matthews (Clarkson University) as Chair, GeorGe Candea (EPFL) as Vice Chair, Dilma da Silva (Qualcomm) as Treasurer and Muli Ben-Yehuda (Technion) as Information Director. As has been typical, elected officers agreed to continue for a second and final two- year term beginning July 2013. Shan Lu (University of Wisconsin) will replace Muli Ben-Yehuda as Information Director as of AuGust 2013. Awards We have an excitinG new award to announce – the SIGOPS Dennis M. Ritchie Doctoral Dissertation Award. SIGOPS has lonG been lackinG a doctoral dissertation award, such as those offered by SIGCOMM, Eurosys, SIGPLAN, and SIGMOD. This new award fills this Gap and also honors the contributions to computer science that Dennis Ritchie made durinG his life. With this award, ACM SIGOPS will encouraGe the creativity that Ritchie embodied and provide a reminder of Ritchie's leGacy and what a difference a person can make in the field of software systems research. The award is funded by AT&T Research and Alcatel-Lucent Bell Labs, companies that both have a strong connection to AT&T Bell Laboratories where Dennis Ritchie did his seminal work. -

Cryptography: DH And

1 ì Key Exchange Secure Software Systems Fall 2018 2 Challenge – Exchanging Keys & & − 1 6(6 − 1) !"#ℎ%&'() = = = 15 & 2 2 The more parties in communication, ! $ the more keys that need to be securely exchanged Do we have to use out-of-band " # methods? (e.g., phone?) % Secure Software Systems Fall 2018 3 Key Exchange ì Insecure communica-ons ì Alice and Bob agree on a channel shared secret (“key”) that ì Eve can see everything! Eve doesn’t know ì Despite Eve seeing everything! ! " (alice) (bob) # (eve) Secure Software Systems Fall 2018 Whitfield Diffie and Martin Hellman, 4 “New directions in cryptography,” in IEEE Transactions on Information Theory, vol. 22, no. 6, Nov 1976. Proposed public key cryptography. Diffie-Hellman key exchange. Secure Software Systems Fall 2018 5 Diffie-Hellman Color Analogy (1) It’s easy to mix two colors: + = (2) Mixing two or more colors in a different order results in + + = the same color: + + = (3) Mixing colors is one-way (Impossible to determine which colors went in to produce final result) https://www.crypto101.io/ Secure Software Systems Fall 2018 6 Diffie-Hellman Color Analogy ! # " (alice) (eve) (bob) + + $ $ = = Mix Mix (1) Start with public color ▇ – share across network (2) Alice picks secret color ▇ and mixes it to get ▇ (3) Bob picks secret color ▇ and mixes it to get ▇ Secure Software Systems Fall 2018 7 Diffie-Hellman Color Analogy ! # " (alice) (eve) (bob) $ $ Mix Mix = = Eve can’t calculate ▇ !! (secret keys were never shared) (4) Alice and Bob exchange their mixed colors (▇,▇) (5) Eve will