Connecting Bangladesh: Economic Corridor Network

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bangladesh Land Port Authority

Bangladesh Land Port Authority OVERVIEW Bangladesh Land Port Authority (BLPA) came into being under Bangladesh Sthala Bandar Kartipaksha Act, 2001 (Act 20 of 2001) to facilitate and improve import and export between Bangladesh and neighbouring countries. Since inception, Bangladesh Land Port Authority has been functioning under the Ministry of Shipping. So far 23 Land Customs Stations have been declared as Land Ports. Of the declared land ports, namely Benapole, Bhomra, Burimari, Akhaura, Nakugaon and Tamabil are being operated by own management of BLPA. On the other hand, Sonamosjid, Hili, Teknaf, Bibirbazar and Banglabandha Land Ports are being operated by Private Port Operators on BOT (Build, Operate and Transfer) basis. A Private Port Operator has also been appointed to develope and operate Birol Land Port. The development of the remaining 11 land ports (Darshona, Belonia, Gobrakura-Koroitoli, Ramgarh, Sonahat, Chilahati, Tegamukh, Daulatganj, Sheola, Dhanua Kamalpur, Balla) is under process. The total number of approved manpower for BLPA is 345. Vision: Facilitating export-import through land routes. Mission: Infrastructure development, efficient cargo handling, improvement of storage facilities, fostering public-private partnership for effective and better service delivery. Activities of BLPA: (1) Formulating policy for development, management expansion, operation and maintenance of all land ports; (2) Engaging operators for receiving, maintaining and dispatching cargoes at land ports; (3) Preparing schedule of tariffs, tolls, rates and fees chargeable to the port users having prior approval of the government; (4) Executing contracts with any person to fulfill the objectives of the Act. (5) Exchanging opinions and communicating with the related countries with the land ports and developing infrastructures as well as extenting trade through co-operation of the organizations concerned to national and international trades for developing and running the port activities smoothly. -

12. FORMULATION of the URBAN TRANSPORT MASTER PLAN Development of the RSTP Urban Transportation Master Plan (1) Methodology

The Project on The Revision and Updating of the Strategic Transport Plan for Dhaka (RSTP) Final Report 12. FORMULATION OF THE URBAN TRANSPORT MASTER PLAN Development of the RSTP Urban Transportation Master Plan (1) Methodology The development of the RSTP Urban Transportation Master Plan adopted the following methodology (see Figure 12.1): (i) Elaborate the master plan network through a screen line analysis by comparing the network capacity and future demand. (ii) Identify necessary projects to meet future demand at the same time avoiding excessive capacity. (iii) Conducts economic evaluation of each project to give priority on projects with higher economic return. (iv) Conduct preliminary environmental assessment of every project and consider countermeasures against environmental problems, if any. (v) Make a final prioritization of all physical projects by examining their respective characteristics from different perspectives. (vi) Classify the projects into three categories, namely short-, medium- and long-term projects, by considering the financial constraints. (vii) Prepare an action plan for short-term projects together with “soft” measures. Mid-term Project Source: RSTP Study Team Figure 12.1 Development Procedure for the Master Plan 12-1 The Project on The Revision and Updating of the Strategic Transport Plan for Dhaka (RSTP) Final Report (2) Output of the Transportation Network Plan The RSTP urban transportation network plan was developed based on a review and a modification of the STP network plan. The main points of the modification or adoption of the STP network master plan are as follows: i. Harmonization with future urban structure, land-use plan and development of network plan. -

Effect of Nitrogen and Boron on the Yield of Wheat Cv. Kanchan

J. Bangladesh Agril. Univ. 3(2): 215-220, 2005 ISSN 1810-3030 Effect of nitrogen and boron on the yield of wheat cv. Kanchan M.M. Khan', A.K. Hasan2, M.H. Rashid2, and F. Ahrned3 Palli Karma Sahayak Foundation (PKSF), Sher-e-Banglanagar, Dhaka, 2Department of Agronomy and 3 Department of Agroforestry, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh Abstract An experiment was carried out at the Agronomy Field Laboratory, Bangladesh Agricultural University, Mymensingh during the period from January to April 2004 to study the effect of different levels of nitrogen and boron on the yield of wheat cv. Kanchan. The treatments included four levels of nitrogen VIZ., 45, 60, 85 and 110 kg N ha-1 and four levels of boron viz., 0, 1, 2 and 3 kg B ha-1. The experiment was laid out in a Randomized Complete Block Design with three replications. The results revealed that Yield and yield contributing characters were influenced significantly by both levels of nitrogen and boron. Among the levels of nitrogen, 110 kg N ha-1 produced the highest grain (5.54 t ha-1)and straw (8.21 t ha-1 ) yields. The lowest grain (3.23 t ha-1) and straw (5.52 t ha-1) yields were observed with the application of 45 kg N ha-1. The highest grain (4.95 t ha-1)and straw (7.38 t ha 1) yields were produced With 3 kg B ha-1. The minimum grain (3.59 t ha-1)and straw (6.14 t ha-1)yields were found in the control treatment. -

Road Investment Strategy 2: 2020-2025

Road Investment Strategy 2: 2020–2025 March 2020 CORRECTION SLIP Title: Road Investment Strategy 2: 2020-25 Session: 2019-21 ISBN: 978-1-5286-1678-2 Date of laying: 11th March 2020 Correction: Removing duplicate text on the M62 Junctions 20-25 smart motorway Text currently reads: (Page 95) M62 Junctions 20-25 – upgrading the M62 to smart motorway between junction 20 (Rochdale) and junction 25 (Brighouse) across the Pennines. Together with other smart motorways in Lancashire and Yorkshire, this will provide a full smart motorway link between Manchester and Leeds, and between the M1 and the M6. This text should be removed, but the identical text on page 96 remains. Correction: Correcting a heading in the eastern region Heading currently reads: Under Construction Heading should read: Smart motorways subject to stocktake Date of correction: 11th March 2020 Road Investment Strategy 2: 2020 – 2025 Presented to Parliament pursuant to section 3 of the Infrastructure Act 2015 © Crown copyright 2020 This publication is licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/ open-government-licence/version/3. Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. This publication is available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications. Any enquiries regarding this publication should be sent to us at https://forms.dft.gov.uk/contact-dft-and-agencies/ ISBN 978-1-5286-1678-2 CCS0919077812 Printed on paper containing 75% recycled fibre content minimum. Printed in the UK by the APS Group on behalf of the Controller of Her Majesty’s Stationery Office. -

July 2016 Volume 3 No 3

6 VOLUME 3 NO 3 JULY 2016 DHAKA CENTRAL INTERNATIONAL MEDICAL COLLEGE JOURNAL (APPROVED BY BMDC) July 2016, Vol. 3 No. 3 Contents From the Desk of Editor-in-Chief 3 Instructions for Authors 4 Editorial Novel Treatment of Diabetic Nephropathy 12 Original Articles Incidence of Malignancy in Thyroid Nodule 14 Abedin SAMA, Alam MM, Islam MS, Fakir MAY Dyslipidemia and Atherogenic Index among the 21 Young Female Doctors ofBangladesh. Khanduker S, Hoque MM, Khanduker N, Chowdhury MAA, Nazneen M A Study on Stroke in Young Patients due to Cardiac 26 Disease in a Tertiary Care Hospital in Dhaka City Mukta M, Mohammad QD, Mir AS Variation of Transverse Diameter ofDry Ossified 33 Human Atlas Vertebra of Male and Female Rahman S, Ara S, Sayeed S, Rashid S, Ferdous Z, Kashem K Study on Health Effects of Teenage Pregnancies among the Patients 36 Attending Antenatal Care Centre of Chittagong Medical College Hospital Tarafdar MA, Begum N, Das SR, Begum S, Sultana A, Rahman R, Begum R Identification ofDifferent Clinical Features and Complications of 41 Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Bengaladeshi Males Begum F, Shamim KM, Akter S, Hossain S, Nazma N, Afrin M, Moureen A Review Articles Female Genital Tuberculosis- A Review Article 46 Shaheed S, Mamun SMAA, Khanom M Case Reports Round Worm induced Acute Appendicitis- an Incidental 51 Finding during Colonoscopy Masum QAA, Islam MN 1 Dhaka Central International Medical College Journal Vol.13 No. 3July 2016 An Official Organ of Dhaka Central International Medical College CHIEF PATRON ADVISORS The Dhaka Central International Prof. Md. Anwarul Islam Md. -

Land Port Declaration

LAND PORT DECLARATION S.L Name Of Port Date of Decleration Part in Bangladesh Part in India/Myanmar 1. Benapole Land Port (S.R.O No.-11, Benapole, Sharsha, Petrapole, Bongaon, 24- Date: 12/01/2002) Jessore Parganas, West Bengal 2. Burimari Land Port (S.R.O No.-11, Burimari, Patgram, Changrabandha, Date: 12/01/2002) Lalmonirhat Mekhaliganj, West Bengal 3. Akhaura Land Port (S.R.O No.-11, Akhaura, Ramnagar, Agartala, Tripura Date: 12/01/2002) Brahmnbaria 4. Sonamasjid Land Port (S.R.O No.-11, S hibganj, Chapai Mahadipur, Maldah, West Date: 12/01/2002) Nawabganj Bengal 5. Hili Land Port (S.R.O No.-11, Hilli, Hakimpur, Hili, South Dinajpur, West Date: 12/01/2002) Dinajpur Bengal 6. Banglabandha Land Port (S.R.O No.-11, Tetulia, Panchagarh Fulbari, Jalpaiguri, West Date: 12/01/2002) Bengal 7. Birol Land Port (S.R.O No.-11, Birol, Dinajpur Radhikapur (Goura), West Date: 12/01/2002) Bengal 8. Teknaf Land Port (S.R.O No.-11, Teknaf, Cox’s Bazar M ungdu, Myanmar Date: 12/01/2002) 9. Tamabil Land Port (S.R.O No.-11, Gowinghat, Sylhet Dauki, Shillong, Meghalaya Date: 12/01/2002) 10. Bhomra Land Port (S.R.O No.-11, Bhomra, Sadar Gojadanga, 24-Parganas, Date: 12/01/2002) Upazila, Satkhira West Bengal 11. Darshana Land Port (S.R.O No.-11, D amurhuda, G ede, Krishnanagar, West Date: 12/01/2002) Chuadanga Bengal 12. Bibirbazar Land Port S.R.O No.- 320, Date: Sadar Upazila, Srimantapur, Sunamura, 18/11/2002 Comilla Agartala, Tripura 13. -

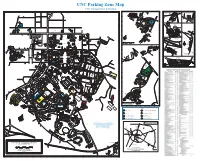

UNC Parking Zone Map UNC Transportation & Parking

UNC Parking Zone Map UNC Transportation & Parking Q R S T U V W X Y Z A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P 26 **UNC LEASES SPACE CAROLINA . ROAD IN THESE BUILDINGS 21 21 MT HOMESTEAD NORTH LAND MGMT. PINEY OPERATIONS CTR. VD. (NC OFFICE HORACE WILLIAMS AIRPORT VD., HILL , JR. BL “RR” 41 1 1 Resident 41 CommuterRR Lot R12 UNC VD AND CHAPEL (XEROX) TE 40 MLK BL A PRINTING RIVE EXTENSION MLK BL ESTES D SERVICES TIN LUTHER KING TERST PLANT N O I AHEC T EHS HOMESTEAD ROAD MAR HANGER VD. 86) O I-40 STORAGE T R11 TH (SEE OTHER MAPS) 22 22 O 720, 725, & 730 MLK, JR. BL R1 T PHYSICAL NOR NORTH STREET ENVRNMEN HL .3 MILES TO TH. & SAFETY ESTES DRIVE 42 COMMUTER LOT T. 42 ER NC86 ELECTRICAL DISTRICENTBUTION OPERATIONS SURPLUS WA REHOUSE N1 ST GENERAL OREROOM 2 23 23 2 R1 CHAPEL HILL ES MLK JR. BOULE NORTH R1 ARKING ARD ILITI R1 / R2OVERFLOW ZONEP V VICES C R A F SHOPS GY SE EY 43 RN 43 ENERBUILDING CONSTRUCTION PRITCHARD STREET R1 NC 86 CHURCH STREET . HO , JR. BOULE ES F R1 / V STREET SER L BUILDING VICE ARD A ST ATIO GI EET N TR AIRPOR R2 S T DRIVE IN LUTHER KING BRANCH T L MAR HIL TH WEST ROSEMARY STREET EAST ROSEMARY STREET L R ACILITIES DRIVE F A NO 24 STUDRT 24 TH COLUMBI IO CHAPE R ADMINIST OFF R NO BUILDINGICE ATIVE R10 1700 N9 MLK 208 WEST 3 N10 FRANKLIN ST. -

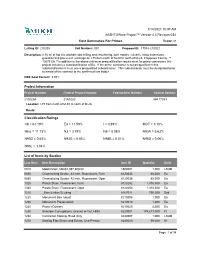

Aashtoware Project™ Version 4.4 Revision 034 1/14/2021 10:37 AM

1/14/2021 10:37 AM AASHTOWare Project™ Version 4.4 Revision 034 Cost Summaries For Primes Report v1 Letting ID: 210205 Call Number: 001 Proposal ID: 17033-210022 Description: 8.30 mi of hot mix asphalt cold milling and resurfacing, joint repairs, culverts, ramp extensions, guardrail and pavement markings on I-75 from north of M-80 to north of M-28, Chippewa County. ** 12075 Cb **In addition to the above minimum prequalification requirement for prime contractors this project includes a subclassification of Ea. If the prime contractor is not prequalified in this subclassification it must use a prequalified subcontractor. This subcontractor must be designated prior to award of the contract to the confirmed low bidder. DBE Goal Percent: 3.00% Project Information Project Number Federal Project Number Federal Item Number Control Section 210022A 21A0220 NH 17033 Location: I-75 from north of M-80 to north of M-28. Route: Classification Ratings Cb = 61.19% Ea = 11.59% I = 0.89% MOT = 3.10% Misc = 11.73% N3 = 3.79% N6 = 0.08% N93A = 5.63% N93D = 0.05% N93G = 0.85% N94B = 0.01% N95D = 0.06% N96L = 1.04% List of Items by Section Line Num Item Description Item ID Quantity Units 0010 Mobilization, Max$1,097,800.00 1500001 1.000 LSUM 0850 Channelizing Device, 42 inch, Fluorescent, Furn 8120035 65.000 Ea 0860 Channelizing Device, 42 inch, Fluorescent, Oper 8120036 65.000 Ea 1020 Plastic Drum, Fluorescent, Furn 8120252 1,310.000 Ea 1030 Plastic Drum, Fluorescent, Oper 8120253 1,310.000 Ea 1210 _Bioretention Seeding 8167011 750.000 Syd 1220 Monument Box -

Supporting Material 1,2,4,3-Triazaborole-Based Neutral

Electronic Supplementary Material (ESI) for ChemComm. This journal is © The Royal Society of Chemistry 2014 Supporting Material 1,2,4,3-Triazaborole-based Neutral Oxoborane Stabilized by a Lewis Acid Ying Kai Loh,‡ Che Chang Chong,‡ Rakesh Ganguly, Yongxin Li, Dragoslav Vidovic, and Rei Kinjo* Division of Chemistry and Biological Chemistry School of Physical and Mathematical Sciences Nanyang Technological University 21 Nanyang link Singapore 637371 (Singapore) Contents: Synthesis, physical and spectroscopic data for all new compounds Theoretical results and IR spectrum References NMR spectra 1. Synthesis, physical and spectroscopic data for all new compounds General considerations: All reactions were performed under an atmosphere of argon by using standard Schlenk or dry box techniques; solvents were dried over Na metal, K metal or CaH2. Reagents were of analytical grade, obtained from commercial suppliers and used without further purification. 1H, 13C, 11B, and 27Al{1H} NMR spectra were obtained with a Bruker AV 300, Bruker AV 400 or Bruker AVIII 400MHz BBFO1, spectrometers at 298 K unless otherwise stated. NMR multiplicities are abbreviated as follows: s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, sept = septet, m = multiplet, br = broad signal. Coupling constants J are given in Hz. Electrospray ionization (ESI) mass spectra were obtained at the Mass Spectrometry Laboratory at the Division of Chemistry and Biological Chemistry, Nanyang Technological University. Melting points were measured with OptiMelt Stanford Research System. IR spectrum was measured using Shimadzu IR Prestige-21 FITR spectrometer. N-(2,6-diisopropylphenyl)pivalimidoyl chloride [(DippN=C(tBu)Cl)] was synthesized according to literature report.[1] Synthesis of compound 1: 1 was generated in situ using a modified literature procedure.[2] Phenyl hydrazine (0.99 t mL, 10.0 mmol) and NEt3 (2.09 mL, 15.0 mmol) were added dropwise to a THF solution of [(DippN=C( Bu)Cl)] (2.80 g, 10.0 mmol). -

Bangladesh Investigation (IR)BG-6 BG-6

BG-6 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROJECT REPORT Bangladesh Investigation (IR)BG-6 GEOLOGIC ASSESSMENT OF THE FOSSIL ENERGY POTENTIAL OF BANGLADESH By Mahlon Ball Edwin R. Landis Philip R. Woodside U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 83- ^ 0O Report prepared in cooperation with the Agency for International Developme U.S. Department of State. This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards. CONTENTS INTPDDUCTION...................................................... 1 REGIONAL GEOLOGY AND STRUCTURAL FRAMEWORK......................... 3 Bengal Basin................................................. 11 Bogra Slope.................................................. 12 Offshore..................................................... 16 ENERGY RESOURCE IDENTIFICATION............................."....... 16 Petroleum.................................................... 16 History of exploration.................................. 17 Reserves and production................................. 28 Natural gas........................................ 30 Recent developments................................ 34 Coal......................................................... 35 Exploration and Character................................ 37 Jamalganj area..................................... 38 Lamakata-^hangarghat area.......................... 40 Other areas........................................ 41 Resources and reserves.................................. -

Beacon of Light

Beacon of Light Beacon of Light A Commemorative Book on National Professor Jamilur Reza Choudhury cªKvkK Published by: Qazi M Arif KvRx Gg Avwid Secretary, Communication & Publication, BUET Alumni F3YL,F.YNEYP~ÔYC._H\gT8*MYJEY% cªKvkKvj Published on: Electronic Edition : April 2021 %gMZE.PVkL<*ZFM P~ÔYCEYFOC Board of Editors .Y5[*J$YZLG__$YQzYT. Qazi M Arif | | Convener NYJP\YJYEGYLÀ. Shamsuzzaman Farooq =YgQLPY%G Taher Saif GYLQY=f5ZLE Ferhat Zerin *f.*JJYP\C AKM Masud .YZLNJYf3jD\L[ Charisma Choudhury Masud Ur Rashid JYP\C'LLZNC To those of Tomorrow - P~ÔYCEYPQgKY0[ Editorial Support Who shall Build a Humane World by the Strength of P\M=YEYfLgH.Y$Y/=YL Sultana Rebeka Akhter Dream, Integrity, Compassion and Technology EYPL[E5YQYE Nasreen Jahan gPYQYEY=YE5[J Sohana Tanzeem Umme Mahfuza Haque 'g~JYQG\5YQ. DEDICATION ZHgNO.d==Y Special Acknowledgement Z5TY,TYC\C Zia Wadud JYQH\H\LfL5Yf3jD\L[ Mahbubur Reza Choudhury 0YZG,ZHEYP Graphics & Layout =YgCLFZ= JYP\C'LLZNC Masud Ur Rashid 'AFxP==YPVgHCEN[M=Y$YL.YZL0ZLC=YZCgTUP0 g3jD\L[F=[.HR\TY Chowdhury Pratick Barua KYLY0RgH$Y0YJ[L*.JYEZH.FdZBH[ NYQ ZLTYLQYPYE Shahriyar Hasan Fp4C Cover J\§YGY/YZMCFMYN Mustapha Khalid Palash 00vnP¥{ Copyright: BUET ALUMNI, Bangladesh 2021 www.buetalumni.org [email protected] ISBN ZHgNOCÍH Disclaimer: 0gvnF.YZN=P.MFH¶fM/g.LHYZ0=J=YJ=,CdZÍIZLDYL.f.YEIYgH%H\gT8 Statements, Comments and Observations mentioned in the Articles published in this book reflect & represent the opinion & perspective of the respective *MYJEY%*LET_ author only and does not incur any responsibility of BUET Alumni. 0 gvnHHÖ=P.M$YgMY.Z3¨PJaQZHZIExJYDJ,Pa¨gBg.PV0eQ[=_5YEY$5YEYgP%P.M The Photographs used are collected from different media and sources which HYZ,F Z=ÎYgELF Z=.e==Y_ are gratefully acknowledged. -

Setu?*Nffi:Ffiilboad

Government of the Peoples Bepublic of Bangladesh Ministrv of C"ommunication s Bangladesh Bridge Authgritv (BBA) setu?*nffi:ffiilBoad Auditors' Report on Financial Statements For The Financial Year 2019-2020 1 ra, Ih MAFazal&Co. Rahman Mostafa AIam & Co. Chqtered Accountutts Chartered Accotmtants 29, Boryabandlru Avenue Pmamomt Heights (7th Floor'D2) (f tl*r), Dlroka-1000. 65/2/1, Box Culvert Road Phone: Aff: 9551991 Purana Paltan, Dhaka- I 000. fu No: 8842-9571824 Plnne: +880-2-9553449 lg-Mail : mafazal c o I 97 0 @pnni l. c om E -moi I : mradlwka@gnai l. e am MAFazal&Co. Rahman Mostafa Alam & Co. Chartered Accountants @ Chartered Accountants I ndependent Auditors' Report To the Executive Director of The Bangladesh Bridge Authority (BBA) Report on the Audit of the Financial Statements Qualified Opinion ,1'/e have audited the financial statements of The Bangladesh Bridge Authority (BBA) (the Entity), lrch comprise the Statement of Financial Position as at June 30,2020 Statement of Profit or Loss e'C Other Comprehensive lncome, Statement of Changes in Equity and Statement of Cash Flows for "-. year then ended, and notes to the financial statements, including a summary of significant ::::-rt ng policies and other explanatory information disclosed in notes 1 to 36 & Annexure-A to D. - : -'-3::l 3 o nion, except for the effect of the matter described in the basis for Qualified opinion section of :-- the accompanying financial statements present fairly, in all material respects, the financial ' : :: : - :f the company as at June 30, 2020, and its financial performance and its cash flows for the ::":-:' ended in accordance with lnternational Financial Reporting Standards (lFRSs), the 1 --:=^ es Act 1994 and other applicable laws and regulations.