Ron Dart, Orthodox Tradition and George Grant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

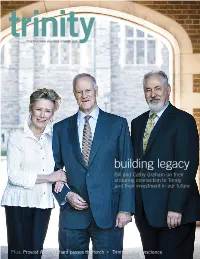

Building Legacy Bill and Cathy Graham on Their Enduring Connection to Trinity and Their Investment in Our Future

trinityTRINITY ALUMNI MAGAZINE SUMMER 2013 building legacy Bill and Cathy Graham on their enduring connection to Trinity and their investment in our future Plus: Provost Andy Orchard passes the torch • Trinity’s eco-conscience provost’smessage Trinity’s Secret Strength A farewell to a team that is PAC-ed with affection For most students, their time at Trinity simply flies by. But those Jonathan Steels, following the departure of Kelley Castle, has rede- four or five years of living and learning and growing and gaining fined the role of Dean of Students and built both community and still linger on, long after the place itself has been left behind. Over consensus. Likewise, our Registrar, Nelson De Melo, had a hard act the past six years as Provost I have been privileged to meet many to follow in Bruce Bowden, but has made his indelible mark already wonderful Men and Women of College, and hear many splen- in remaking his entire office. did stories. I write this in the wake of Reunion, that wondrous Another of the newcomers who has recruited well and widely is weekend of memories made and recalled and rekindled, and Alana Silverman: there is renewed energy and purpose in the Office friendships new and old found and further fostered. In my last of Development and Alumni Affairs, to which Alana brings fresh column as Provost, it is the thought of returning to the College vision and an alternative perspective. A consequence of all this activ- that moves me most, and makes me want to look forward, as well ity across so many departments is the increased workload of Helen as back, and to celebrate those who will run the place long after Yarish, who replaced Jill Willard, and has again through admirable this Provost has gone. -

Book Reviews

333 Book Reviews E. Shragge, R. Babin, and J.G. Vaillancourt, (Editors). ROOTS OF PEACE: THE MOVEMENT AGAINST MIUTARISM IN CANADA. Toronto: Between the Lines, 1986. 203 pp. $12.95 Roots of Peace: The Movemenl Against Militarism in Canada is a collection of articles on a wide range of peace-re1ated issues, from Canada's role in NATO to liberation struggles in the Third World. The book's contributors include disannament activists, feminists, community organizers, academics, and a retired general. However, despite this diversity of issues and perspectives, the book's 13 articles leave one with a single, two-part message. The flCSt part: Canada is a full and voluntary player in the anns race. We are told to look beyond Washington and Moscow to find reasons for increased global militarization. We should look closer to home, at our communities, our places of work. We should look to Canada's economic system, its profit from anns sales, its tteatment of women and developing nations, its relationship with the U.S. The second part of the book's message is that Canadians cao do something to halt the anns race. The reader is advised, however, to put little hope in politicians or superpower summits. Again, we should look closer to home, at ourselves, our involvenient in efforts for peace. The book has two sections: "An International Perspective on the Peace Movement" and "Organizing for Peace." The first section places Canadian involvement in the anns race into a global context and deals with sorne of the larger issues: Canada's role in NATO and its relationship to the U.S., disarmament movements in Europe, the Third World and supeIpOwer politics, the need for a non-aligned peace movement, and that perennial question, "What about the Russians?" 334 Book Reviews The second section describes specific examples of what the Editors calI "detente from below"; that is, a grassroots movement of ordinary people committed to breaking the cycles of power and paranoïa which keep all of us locked in the arms race. -

Canada's Response to the 1968 Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia

Canada’s Response to the 1968 Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia: An Assessment of the Trudeau Government’s First International Crisis by Angus McCabe A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2019 Angus McCabe ii Abstract The new government of Pierre Trudeau was faced with an international crisis when, on 20 August 1968, the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia. This study is the first full account of the Canadian government’s response based on an examination of the archival records of the Departments of External Affairs, National Defence, Manpower and Immigration, and the Privy Council Office. Underlying the government’s reaction were differences of opinion about Canada’s approach to the Cold War, its role at the United Nations and in NATO, the utility of the Department of External Affairs, and decisions about refugees. There was a delusory quality to each of these perspectives. In the end, an inexperienced government failed to heed some of the more competent advice it received concerning how best to meet Canada’s interests during the crisis. National interest was an understandable objective, but in this case, it was pursued at Czechoslovakia’s expense. iii Acknowledgements As anyone in my position would attest, meaningful work with Professor Norman Hillmer brings with it the added gift of friendship. The quality of his teaching, mentorship, and advice is, I suspect, the stuff of ages. I am grateful for the privilege of his guidance and comradeship. Graduate Administrator Joan White works kindly and tirelessly behind the scenes of Carleton University’s Department of History. -

Vol. 35, No. 1 (Mar. 2009)

VOL XXXV, NO. 1 - MARCH 2009 Friesens in Altona, was willing to tackle the project, strongly supported by persons like Ted Friesen, J. Winfield Fretz and others. It would take a number of years and now stands, in its three volumes, written by Frank (now deceased), and then helped by Ted Regehr, as a Mennonite monument to that idea. My involvement would be limited later on to reader services and promotion of sales to a limited degree. In the early 1970s things changed quite a bit. The celebration of the centennial (1874-1974) of Mennonite settlement in Historian Manitoba had become the topical issue of the day. MMHS undertook to lead these A PUBLICATION OF THE MENNONITE HERITAGE CENTRE and THE CENTRE FOR MB STUDIES IN CANADA celebrations. A special Steering Committee to direct the planning was set up, and I gave some time to serve as executive secretary with an office in Altona where we were teaching after returning from University of Minnesota graduate studies about that time. Gerhard Ens began a program of Low German Mennonite history lectures on CFAM around 1972, devoted at first to promotion of the museum well established in Steinbach by then, and then moving into promotion of the Mennonite story as a whole. One of the projects where I became An evening playing Mennonite circle games on November 21, 2008 in Winkler brought fun personally quite involved was that of and laughter to the Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society 50th Anniversary Celebration. erecting a cairn in honour of the one-time Photo credit: Conrad Stoesz. -

Escott Reid, Canadian Diplomat

THE PASSION OF ESCOTT REID: A CANADIAN TEMPLATE FOR MODERN DIPLOMACY? Since the Berlin wall crumbled, on 9th November 1989, we have had 15 years in which to seek the “peace dividend", and the spread of democracy so energetically trumpeted by the victors of the Cold War. While it is true that Latin American dictators may be an endangered species, in too many parts of the world there is a resurgence of ethnic strife and the worst manifestations of nationalism. The only surviving superpower's military spending keeps rising to drive the national debt. The United Nations all too often seems as impotent now as it did in the Security-council veto days of its infancy. The 51 member states in December 1945 have grown steadily to 191 at the end of 2002. Indecision, conflicts of interest and plain apathy can all impede rapid response in a crisis. Well, what about diplomacy? Perhaps we must go back in order to progress, and review the life and times of one of Canada's most eminent diplomats. Today, 21 Prime Ministers and 137 years removed from Confederation, many Canadians may not think that the country has much diplomacy of which to boast. This was certainly not the case in the central decades of the 20th century. Canada had an active foreign service, with some exemplary strategists and negotiators. One such was Escott Meredith Reid, a tenacious worker, who was by turns Rhodes scholar, political researcher, career diplomat, World Bank regional director and the founding principal of Glendon College at York University in Toronto. -

Trinity's Students: What Are They Thinking?

Trinity Trinity Alumni Magazine Summer 2015 Trinity’s students: What are they thinking? Plus: The Trinity Book Sale turns 40 The (in)famous Trinity Escapades hockey team Note from the editor Changes are always a bit of a gamble. That’s why we’re pleased that so many of you have responded so positively to our refreshed approach to Trinity magazine. s we promised in our last issue, also find links on the website to send Check us out online at A we’re growing our online channels us your news, update your address and magazine.trinity.utoronto.ca to offer you more ways of connecting preferences, link to the Trinity online with your College. In that spirit, we’re events calendar, donate to the College, Trinity proud to officially launch the Trinity and more. magazine website at magazine.trinity. Please check it out and let us utoronto.ca. know what you think. Start an online This new format will supplement conversation about one of the stories. the print edition of the magazine and We’re listening. offer you the opportunity to connect more directly with us, and with each other. Want to respond to something Trinity Alumni Magazine Spring 2015 you’ve read? It’s as simple as inputting your name, your comment, and clicking “post” to get the conversation started. One on One: John Allemang ’74 In addition to a more interactive, sits down with John Tory ’75 online layout of the magazine, you’ll Plus: An epic Arctic discovery Baillies boost student support Congratulations! Congrats to Shauna Gundy ’14, who was Co-Head of Divinity in 2011 and 2012 and is currently working toward her Master of Divinity degree at Trinity. -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1994

1NS1DE: - ^ Countdown to election day in Ukraine - page 2. l ' f e Pre-election opinions from Dnipropetrovske - page 3. І ^ Minister of sport comments on Ukraine's Olympic showing - page 9-І 1 -п^Стшт -"^ THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY Published by the Ukrainian National Association inc., a fraternal non-profit association vol. LXII No. 12 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, MARCH 20,1994 50 cents Nixon comes calling in Kyyiv Ukrainian president invalidates stresses Ukraine's vital importance' referendum on Crimea's status by Marta Kolomayets "1 wish my schedule would permit by Marta Kolomayets plebiscite, it includes questions on dual cit– Kyyiv Press Bureau this, to meet with opposition leaders. Kyyiv Press Bureau izenship and the adaptation of a Crimean And, 1 received a letter from Mr. Constitution, which was passed in May KYYiv - Former U.S. President KYYiv - President Leonid Kravchuk Kravchuk indicating that 1 should do so," 1992 and repealed three month later. Richard Nixon called on Ukrainian annulled the Crimean referendum late he added. "We would not have had a "it is proposed that citizens of the President Leonid Kravchuk during a Tuesday evening, March 15, calling the Yeltsin incident here in Ukraine," he told Crimea answer questions concerning the brief visit to Kyyiv on Wednesday, action unconstitutional. reporters who met with him and Mr. basis of Ukraine's Constitution, relations March 16. Slated for the same day as parliamen– Kravchuk after their closed meeting. between the Crimea and Ukraine and the During a one-hour meeting with the tary elections in Ukraine - Sunday, At the airport, Mr. -

Michael Ignatieff, the Man

UNIVERSIDAD DE ALMERÍA Facultad de Humanidades y Psicología (División Humanidades) GRADO EN ESTUDIOS INGLESES Curso Académico: 2013/2014 Convocatoria (Junio/Septiembre): JUNIO Trabajo Fin de Grado: AN ANALYSIS OF LOVE AND WAR IN ASYA (1991) BY MICHAEL IGNATIEFF - Autor/a – MARINA ASIÁN CAPARRÓS - Tutor/a – JOSÉ CARLOS REDONDO OLMEDILLA Summary This work is dedicated to a great contemporary Canadian author, Michael Ignatieff, and more especially, to the analysis of his work Asya regarding two of its key themes: love and war. Throughout this project, different aspects related to Ignatieff’s various facets shall be studied, since he has worked also as a journalist, offering us a valuable perspective of the most relevant and current issues. I will also analyze the relationship between his diverse journal articles, including the ideas he puts forwards on them, and the work of Asya , evaluating the influence that his familiar inheritance has also had upon his work. Later on, I shall provide a study of two of the most universal themes discussed in literature, love and war, through numerous theories and considering the value they have been gaining along history. The original text will be the base for the most significant quotations to exemplify what has been said previously. Finally, some conclusions are set out to finish with this work in order to synthesise the main ideas developed aforesaid and, above all, exalting this peculiar author. Resumen Este trabajo de investigación está dedicado a un gran autor contemporáneo canadiense, Michael Ignatieff, y en especial, al análisis de su obra Asya en relación con dos de sus temas clave: el amor y la guerra. -

The Yes Man Forty Years of Volunteering and George Fierheller Still Can’T Say No

trinityTRINITY ALUMNI MAGAZINE SUMMER 2010 the yes man Forty years of volunteering and George Fierheller still can’t say no Plus: Students who embody the spirit of service provost’smessage Strong Connections Trinity has much to exchange with the wider world It took a volcano from Iceland to remind us all how intercon- combined and confederated crowns of Trinity, the U of T and nected and thus how easily prone to disruption-through-erup- Canada in the years ahead. tion our ever-shrinking world has become. This year we also had our first Roy McMurtry Community As it happens, the site of the eruption is not far from a place close Outreach Don, among whose activities was a highly successful to my own heart, where I spent nine consecutive summers as a fundraising Coffee House in the Lodge in aid of Haiti, co-spon- tour guide in the mountains. So every time a reporter butchered sored by the Trinity College Volunteer Society, and the third the name Eyjafjallajökull (literally “glacier of the mountains of year of the highly successful Humanities for Humanity program, the isles”), I recalled that long ago, the wider area was named which has involved countless past and present students as men- Landeyjrar (“land-isles”) because in that massive floodplain, tors, lecturers and assistants. H4H (as we call it) is the brainchild caused by earlier eruptions, every single dwelling stands out like of Kelley Castle and John Duncan, and as Kelley heads off to be an island in an ocean. It’s a stubborn reminder of how human- the Dean of Students at Victoria College, we look forward to a ity rightly refuses to be swept away. -

In February 2005, Canadian Prime Minister Paul Martin Rejected Canada’S Participation in the Ballistic Missile Defense (BMD) System Proposed by U.S

HerEisendhower, Canada, and Continental Air Defense, 1953–1954 A “Common Appreciation” Eisenhower, Canada, and Continental Air Defense, 1953–1954 ✣ Alexander W. G. Herd In February 2005, Canadian Prime Minister Paul Martin rejected Canada’s participation in the ballistic missile defense (BMD) system proposed by U.S. President George W. Bush. Martin’s decision was based on domestic political calculations. He had promised that he would “vigorously” defend Canada’s sovereignty against unilateral U.S. action in Canadian airspace.1 The BMD proposal was not the ªrst time Canada had faced extensive U.S. plans for the missile defense of North America. In the 1980s President Ronald Rea- gan had proposed the Strategic Defense Initiative (SDI).2 For many Canadi- ans, the U.S. BMD proposal exempliªed the Canadian-U.S. defense relation- ship formulated during the Cold War: U.S. pressure to coordinate Canadian defense policy with U.S. policy, Canadian concern for territorial sovereignty (particularly in the Canadian Arctic), an economic tug-of-war between U.S. and Canadian businesses, Canadian and U.S. public opinion on the extent of defense cooperation between the two countries, and the Canadian struggle for equal partnership with the United States in continental defense projects. For many scholars, the Canadian-U.S. defense relationship during the Cold War was characterized by Canada’s subordination, necessary or not, to 1. Daniel Leblanc and Paul Koring, “Canada Won’t Allow U.S. Missiles to Impugn Sovereignty, PM Vows,” The Globe and Mail (Toronto), 26 February 2005, p. 1. This news article notes that “sov- ereignty” does not extend into space, where missile interception would occur. -

Pierre Trudeau and the “Suffocation” of the Nuclear Arms Race

Pierre Trudeau and the “Suffocation” of the Nuclear Arms Race Paul Meyer Simons Papers in Security and Development No. 52/2016 | August 2016 Simons Papers in Security and Development No. 52/2016 2 The Simons Papers in Security and Development are edited and published at the School for International Studies, Simon Fraser University. The papers serve to disseminate research work in progress by the School’s faculty and associated and visiting scholars. Our aim is to encourage the exchange of ideas and academic debate. Inclusion of a paper in the series should not limit subsequent publication in any other venue. All papers can be downloaded free of charge from our website, www.sfu.ca/internationalstudies. The series is supported by the Simons Foundation. Series editor: Jeffrey T. Checkel Managing editor: Martha Snodgrass Meyer, Paul, Pierre Trudeau and the “Suffocation” of the Nuclear Arms Race, Simons Papers in Security and Development, No. 52/2016, School for International Studies, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver, August 2016. ISSN 1922-5725 Copyright for this working paper: Paul Meyer, pmeyer(at)sfu.ca. Reproduction for other purposes than personal research, whether in hard copy or electronically, requires the consent of the author(s). If cited or quoted, reference should be made to the full name of the author(s), the title, the working paper number and year, and the publisher. Note: The final, definitive version of this paper has been published in International Journal 71(3), September 2016, by SAGE Publications Ltd. All rights reserved. http://online.sagepub.com DOI 10.1177/00207020/6662798. School for International Studies Simon Fraser University Suite 7200 - 515 West Hastings Street Vancouver, BC Canada V6B 5K3 Pierre Trudeau and the Nuclear Arms Race 3 Pierre Trudeau and the “Suffocation” of the Nuclear Arms Race Simons Papers in Security and Development No. -

Description and Finding Aid GEORGE IGNATIEFF FONDS F2020

Description and Finding Aid GEORGE IGNATIEFF FONDS F2020 Prepared by Lynn McIntyre April 2013 GEORGE IGNATIEFF FONDS Dates of creation: [191-?] - 1989 Extent: 9 m of textual records Approximately 770 photographs 5 scrapbooks 24 audiovisual records Biographical sketch: George Ignatieff, diplomat and administrator, was born into a Russian aristocratic family in St. Petersburg in 1913. He was the fifth and youngest son of Count Paul Ignatieff and Natalie Ignatieff (née Princess Mestchersky). After fleeing Russia during the Bolshevik Revolution, the family arrived in England in 1920. By the end of that decade they had relocated to Upper Melbourne, Quebec. George Ignatieff was educated at Lower Canada College, Montreal, and in Toronto at Central Technical School and Jarvis Collegiate. In 1936 he graduated with a BA in Political Science and Economics from Trinity College, and then went to Oxford on a Rhodes Scholarship, completing his MA in Slavic Studies in 1938. At Lester B. Pearson's suggestion, Ignatieff wrote the External Affairs examination in 1939 and began working at Canada House in London. He returned to the Department of External Affairs in Ottawa in 1944. His many postings included: Canadian Ambassador to Yugoslavia (1956-1958), Assistant Undersecretary of State for External Affairs (1960-1962), Permanent Representative to NATO in 1963, and Canadian Ambassador to the UN (1966-1969). In 1972, Ignatieff left the post of Permanent Representative of Canada to the European Office of the UN at Geneva (from 1970) to become ninth Provost and Vice-chancellor of Trinity College, a position he held until 1979. From 1980 to 1986 he was Chancellor of the University of Toronto.