MURDER by SLANDER? a RE-EXAMINATION of the E.H. NORMAN CASE by C M . ANN ROGERS .A., the University of British Columbia, 1986 K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MARCEL CADIEUX, the DEPARTMENT of EXTERNAL AFFAIRS, and CANADIAN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS: 1941-1970

MARCEL CADIEUX, the DEPARTMENT of EXTERNAL AFFAIRS, and CANADIAN INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS: 1941-1970 by Brendan Kelly A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto © Copyright by Brendan Kelly 2016 ii Marcel Cadieux, the Department of External Affairs, and Canadian International Relations: 1941-1970 Brendan Kelly Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Toronto 2016 Abstract Between 1941 and 1970, Marcel Cadieux (1915-1981) was one of the most important diplomats to serve in the Canadian Department of External Affairs (DEA). A lawyer by trade and Montreal working class by background, Cadieux held most of the important jobs in the department, from personnel officer to legal adviser to under-secretary. Influential as Cadieux’s career was in these years, it has never received a comprehensive treatment, despite the fact that his two most important predecessors as under-secretary, O.D. Skelton and Norman Robertson, have both been the subject of full-length studies. This omission is all the more glaring since an appraisal of Cadieux’s career from 1941 to 1970 sheds new light on the Canadian diplomatic profession, on the DEA, and on some of the defining issues in post-war Canadian international relations, particularly the Canada-Quebec-France triangle of the 1960s. A staunch federalist, Cadieux believed that French Canadians could and should find a place in Ottawa and in the wider world beyond Quebec. This thesis examines Cadieux’s career and argues that it was defined by three key themes: his anti-communism, his French-Canadian nationalism, and his belief in his work as both a diplomat and a civil servant. -

A Perennial Problem”: Canadian Relations with Hungary, 1945-65

Hungarian Studies Review, Vol. XLIII, Nos. 1-2 (Spring-Fall, 2016) “A Perennial Problem”: Canadian Relations with Hungary, 1945-65 Greg Donaghy1 2014-15 marks the 50th anniversary of the establishment of Canadian- Hungarian diplomatic relations. On January 14, 1965, under cold blue skies and a bright sun, János Bartha, a 37-year-old expert on North Ameri- can affairs, arrived in the cozy, wood paneled offices of the Secretary of State for External Affairs, Paul Martin Sr. As deputy foreign minister Marcel Cadieux and a handful of diplomats looked on, Bartha presented his credentials as Budapest’s first full-time representative in Canada. Four months later, on May 18, Canada’s ambassador to Czechoslovakia, Mal- colm Bow, arrived in Budapest to present his credentials as Canada’s first non-resident representative to Hungary. As he alighted from his embassy car, battered and dented from an accident en route, with its fender flag already frayed, grey skies poured rain. The contrasting settings in Ottawa and Budapest are an apt meta- phor for this uneven and often distant relationship. For Hungary, Bartha’s arrival was a victory to savor, the culmination of fifteen years of diplo- matic campaigning and another step out from beneath the shadows of the postwar communist take-over and the 1956 Hungarian Revolution. For Canada, the benefits were much less clear-cut. In the context of the bitter East-West Cold War confrontation, closer ties with communist Hungary demanded a steep domestic political price in exchange for a bundle of un- certain economic, consular, and political gains. -

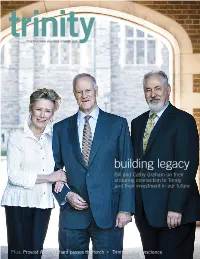

Building Legacy Bill and Cathy Graham on Their Enduring Connection to Trinity and Their Investment in Our Future

trinityTRINITY ALUMNI MAGAZINE SUMMER 2013 building legacy Bill and Cathy Graham on their enduring connection to Trinity and their investment in our future Plus: Provost Andy Orchard passes the torch • Trinity’s eco-conscience provost’smessage Trinity’s Secret Strength A farewell to a team that is PAC-ed with affection For most students, their time at Trinity simply flies by. But those Jonathan Steels, following the departure of Kelley Castle, has rede- four or five years of living and learning and growing and gaining fined the role of Dean of Students and built both community and still linger on, long after the place itself has been left behind. Over consensus. Likewise, our Registrar, Nelson De Melo, had a hard act the past six years as Provost I have been privileged to meet many to follow in Bruce Bowden, but has made his indelible mark already wonderful Men and Women of College, and hear many splen- in remaking his entire office. did stories. I write this in the wake of Reunion, that wondrous Another of the newcomers who has recruited well and widely is weekend of memories made and recalled and rekindled, and Alana Silverman: there is renewed energy and purpose in the Office friendships new and old found and further fostered. In my last of Development and Alumni Affairs, to which Alana brings fresh column as Provost, it is the thought of returning to the College vision and an alternative perspective. A consequence of all this activ- that moves me most, and makes me want to look forward, as well ity across so many departments is the increased workload of Helen as back, and to celebrate those who will run the place long after Yarish, who replaced Jill Willard, and has again through admirable this Provost has gone. -

What Has He Really Done Wrong?

The Chrétien legacy Canada was in such a state that it WHAT HAS HE REALLY elected Brian Mulroney. By this stan- dard, William Lyon Mackenzie King DONE WRONG? easily turned out to be our best prime minister. In 1921, he inherited a Desmond Morton deeply divided country, a treasury near ruin because of over-expansion of rail- ways, and an economy gripped by a brutal depression. By 1948, Canada had emerged unscathed, enriched and almost undivided from the war into spent last summer’s dismal August Canadian Pension Commission. In a the durable prosperity that bred our revising a book called A Short few days of nimble invention, Bennett Baby Boom generation. Who cared if I History of Canada and staring rescued veterans’ benefits from 15 King had halitosis and a professorial across Lake Memphrémagog at the years of political logrolling and talent for boring audiences? astonishing architecture of the Abbaye launched a half century of relatively St-Benoît. Brief as it is, the Short History just and generous dealing. Did anyone ll of which is a lengthy prelude to tries to cover the whole 12,000 years of notice? Do similar achievements lie to A passing premature and imperfect Canadian history but, since most buy- the credit of Jean Chrétien or, for that judgement on Jean Chrétien. Using ers prefer their own life’s history to a matter, Brian Mulroney or Pierre Elliott the same criteria that put King first more extensive past, Jean Chrétien’s Trudeau? Dependent on the media, and Trudeau deep in the pack, where last seven years will get about as much the Opposition and government prop- does Chrétien stand? In 1993, most space as the First Nations’ first dozen aganda, what do I know? Do I refuse to Canadians were still caught in the millennia. -

Book Reviews

333 Book Reviews E. Shragge, R. Babin, and J.G. Vaillancourt, (Editors). ROOTS OF PEACE: THE MOVEMENT AGAINST MIUTARISM IN CANADA. Toronto: Between the Lines, 1986. 203 pp. $12.95 Roots of Peace: The Movemenl Against Militarism in Canada is a collection of articles on a wide range of peace-re1ated issues, from Canada's role in NATO to liberation struggles in the Third World. The book's contributors include disannament activists, feminists, community organizers, academics, and a retired general. However, despite this diversity of issues and perspectives, the book's 13 articles leave one with a single, two-part message. The flCSt part: Canada is a full and voluntary player in the anns race. We are told to look beyond Washington and Moscow to find reasons for increased global militarization. We should look closer to home, at our communities, our places of work. We should look to Canada's economic system, its profit from anns sales, its tteatment of women and developing nations, its relationship with the U.S. The second part of the book's message is that Canadians cao do something to halt the anns race. The reader is advised, however, to put little hope in politicians or superpower summits. Again, we should look closer to home, at ourselves, our involvenient in efforts for peace. The book has two sections: "An International Perspective on the Peace Movement" and "Organizing for Peace." The first section places Canadian involvement in the anns race into a global context and deals with sorne of the larger issues: Canada's role in NATO and its relationship to the U.S., disarmament movements in Europe, the Third World and supeIpOwer politics, the need for a non-aligned peace movement, and that perennial question, "What about the Russians?" 334 Book Reviews The second section describes specific examples of what the Editors calI "detente from below"; that is, a grassroots movement of ordinary people committed to breaking the cycles of power and paranoïa which keep all of us locked in the arms race. -

H-Diplo Roundtables, Vol. XII, No. 9

2011 H-Diplo H-Diplo Roundtable Review Roundtable Editors: Thomas Maddux and Diane Labrosse www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables Roundtable Web/Production Editor: George Fujii Volume XII, No. 9 (2011) 16 March 2011 Introduction by David Webster, University of Regina [23 March 2011, Rev. 2] Adam Chapnick. Canada's Voice: The Public Life of John Wendell Holmes. Vancouver, Canada: University of British Columbia Press, 2009. 384 pp. ISBN: 978-0-7748-16717 (hardcover, $85.00); 978-0-7748-1672-4 (paperback, $32.95). Stable URL: http://www.h-net.org/~diplo/roundtables/PDF/Roundtable-XII-9.pdf Contents Introduction by David Webster, University of Regina .............................................................. 2 Review by Andrew Burtch, Canadian War Museum................................................................. 6 Review by Michael K. Carroll, Grant MacEwan University ..................................................... 11 Review by Alan K. Henrikson, The Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Tufts University . 14 Review by Bruce Muirhead, University of Waterloo .............................................................. 17 Review by Kim Richard Nossal, Queen’s University, Kingston Canada .................................. 21 Response by Adam Chapnick .................................................................................................. 24 Copyright © 2011 H-Net: Humanities and Social Sciences Online. H-Net permits the redistribution and reprinting of this work for non-profit, educational purposes, with full and accurate -

Download The

Middle Power Continuity: Canada-US Relations and Cuba, 1961-1962 by Steven O’Reilly B.A., Thompson Rivers University, 2016 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (History) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) August 2018 © Steven O’Reilly, 2018 The following individuals certify that they have read, and recommend to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies for acceptance, a thesis/dissertation entitled: MIDDLE POWER CONTINUITY: CANADA-US RELATIONS AND CUBA, 1961-1962 Submitted by STEVEN O’REILLY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in HISTORY Examining Committee: HEIDI J.S. TWOREK, HISTORY Co-Supervisor STEVEN H. LEE, HISTORY Co-Supervisor BRADLEY J. MILLER, HISTORY Additional Examiner ii Abstract This thesis examines the work of Canada’s Department of External Affairs and its Undersecretary of State for External Affairs Norman Robertson during tense relations between Canada and the United States in 1961 and 1962. More specifically, this project uses the topic of Cuba in Canada-US relations during the Diefenbaker-Kennedy years as a flash point of how the DEA developed its own Canadian policy strategy that exacerbated tensions between Canada and the United States. This essay argues that the DEA’s policy formation on Cuba during the Kennedy years both reflected a broader continuity in Canadian foreign policy and exacerbated bilateral tensions during a period when tensions have often been blamed primarily on the clash of leaders. The compass guiding Canadian bureaucrats at the DEA when forming policy was often pointed towards Canada’s supposed middle power role within international affairs, a position that long-predated the Diefenbaker years but nevertheless put his government on a collision course with the United States. -

Canada's Response to the 1968 Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia

Canada’s Response to the 1968 Soviet Invasion of Czechoslovakia: An Assessment of the Trudeau Government’s First International Crisis by Angus McCabe A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Affairs in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario © 2019 Angus McCabe ii Abstract The new government of Pierre Trudeau was faced with an international crisis when, on 20 August 1968, the Soviet Union invaded Czechoslovakia. This study is the first full account of the Canadian government’s response based on an examination of the archival records of the Departments of External Affairs, National Defence, Manpower and Immigration, and the Privy Council Office. Underlying the government’s reaction were differences of opinion about Canada’s approach to the Cold War, its role at the United Nations and in NATO, the utility of the Department of External Affairs, and decisions about refugees. There was a delusory quality to each of these perspectives. In the end, an inexperienced government failed to heed some of the more competent advice it received concerning how best to meet Canada’s interests during the crisis. National interest was an understandable objective, but in this case, it was pursued at Czechoslovakia’s expense. iii Acknowledgements As anyone in my position would attest, meaningful work with Professor Norman Hillmer brings with it the added gift of friendship. The quality of his teaching, mentorship, and advice is, I suspect, the stuff of ages. I am grateful for the privilege of his guidance and comradeship. Graduate Administrator Joan White works kindly and tirelessly behind the scenes of Carleton University’s Department of History. -

Vol. 35, No. 1 (Mar. 2009)

VOL XXXV, NO. 1 - MARCH 2009 Friesens in Altona, was willing to tackle the project, strongly supported by persons like Ted Friesen, J. Winfield Fretz and others. It would take a number of years and now stands, in its three volumes, written by Frank (now deceased), and then helped by Ted Regehr, as a Mennonite monument to that idea. My involvement would be limited later on to reader services and promotion of sales to a limited degree. In the early 1970s things changed quite a bit. The celebration of the centennial (1874-1974) of Mennonite settlement in Historian Manitoba had become the topical issue of the day. MMHS undertook to lead these A PUBLICATION OF THE MENNONITE HERITAGE CENTRE and THE CENTRE FOR MB STUDIES IN CANADA celebrations. A special Steering Committee to direct the planning was set up, and I gave some time to serve as executive secretary with an office in Altona where we were teaching after returning from University of Minnesota graduate studies about that time. Gerhard Ens began a program of Low German Mennonite history lectures on CFAM around 1972, devoted at first to promotion of the museum well established in Steinbach by then, and then moving into promotion of the Mennonite story as a whole. One of the projects where I became An evening playing Mennonite circle games on November 21, 2008 in Winkler brought fun personally quite involved was that of and laughter to the Manitoba Mennonite Historical Society 50th Anniversary Celebration. erecting a cairn in honour of the one-time Photo credit: Conrad Stoesz. -

Arnold Heeney, the Cabinet War Committee, and the Establishment of a Canadian Cabinet Secretariat During the Second World War

Study in Documents Memos and Minutes: Arnold Heeney, the Cabinet War Committee, and the Establishment of a Canadian Cabinet Secretariat During the Second World War BRIAN MASSCHAELE* RÉSUMÉ Le Cabinet fédéral canadien n’a pas créé ni maintenu d’archives telles que des procès-verbaux avant mars 1940, date à laquelle les responsabilités du greffier du Conseil privé furent alors amendées pour y inclure le secrétariat du Cabinet. Cela représentait un développement significatif dans le contexte de la longue tradition de secret entourant les délibérations du Cabinet. Cette décision fut prise, du moins à l’origine, à cause des circonstances particulières imposées par la Deuxième Guerre mondiale. Le Cabinet avait besoin d’un système plus efficace de prise de décision et de communication de ses propres arrêts du fait de leur nature urgente. Le poste de secrétaire fut donc établi pour permettre d’acquérir une documentation justificative, créer des ordres du jour, établir des procès-verbaux et donner suite aux décisions du Comité de la guerre du Cabinet (qui dans les faits se substitua au Cabinet au cours de la guerre). Arnold Heeney fut le premier à occuper ce nouveau poste de greffier du Con- seil privé et de secrétaire du Cabinet. Heeney réussit à créer un secrétariat non partisan au service du Cabinet sur la foi d’un précédent britannique et nonobstant les réserves exprimées initialement par le premier ministre Mackenzie King. Cet article examine l’évolution du secrétariat du Cabinet et la gestion des documents qu’il développa au cours de la Deuxième Guerre mondiale. Cette information est ensuite utilisée pour éclairer encore davantage les témoignages qu’offrent les archives du Cabinet fédéral. -

Escott Reid, Canadian Diplomat

THE PASSION OF ESCOTT REID: A CANADIAN TEMPLATE FOR MODERN DIPLOMACY? Since the Berlin wall crumbled, on 9th November 1989, we have had 15 years in which to seek the “peace dividend", and the spread of democracy so energetically trumpeted by the victors of the Cold War. While it is true that Latin American dictators may be an endangered species, in too many parts of the world there is a resurgence of ethnic strife and the worst manifestations of nationalism. The only surviving superpower's military spending keeps rising to drive the national debt. The United Nations all too often seems as impotent now as it did in the Security-council veto days of its infancy. The 51 member states in December 1945 have grown steadily to 191 at the end of 2002. Indecision, conflicts of interest and plain apathy can all impede rapid response in a crisis. Well, what about diplomacy? Perhaps we must go back in order to progress, and review the life and times of one of Canada's most eminent diplomats. Today, 21 Prime Ministers and 137 years removed from Confederation, many Canadians may not think that the country has much diplomacy of which to boast. This was certainly not the case in the central decades of the 20th century. Canada had an active foreign service, with some exemplary strategists and negotiators. One such was Escott Meredith Reid, a tenacious worker, who was by turns Rhodes scholar, political researcher, career diplomat, World Bank regional director and the founding principal of Glendon College at York University in Toronto. -

Trinity's Students: What Are They Thinking?

Trinity Trinity Alumni Magazine Summer 2015 Trinity’s students: What are they thinking? Plus: The Trinity Book Sale turns 40 The (in)famous Trinity Escapades hockey team Note from the editor Changes are always a bit of a gamble. That’s why we’re pleased that so many of you have responded so positively to our refreshed approach to Trinity magazine. s we promised in our last issue, also find links on the website to send Check us out online at A we’re growing our online channels us your news, update your address and magazine.trinity.utoronto.ca to offer you more ways of connecting preferences, link to the Trinity online with your College. In that spirit, we’re events calendar, donate to the College, Trinity proud to officially launch the Trinity and more. magazine website at magazine.trinity. Please check it out and let us utoronto.ca. know what you think. Start an online This new format will supplement conversation about one of the stories. the print edition of the magazine and We’re listening. offer you the opportunity to connect more directly with us, and with each other. Want to respond to something Trinity Alumni Magazine Spring 2015 you’ve read? It’s as simple as inputting your name, your comment, and clicking “post” to get the conversation started. One on One: John Allemang ’74 In addition to a more interactive, sits down with John Tory ’75 online layout of the magazine, you’ll Plus: An epic Arctic discovery Baillies boost student support Congratulations! Congrats to Shauna Gundy ’14, who was Co-Head of Divinity in 2011 and 2012 and is currently working toward her Master of Divinity degree at Trinity.