THE NUCLEAR NORTH Histories of Canada in the Atomic Age

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cuban Missile Crisis JCC: USSR

asdf PMUNC 2015 Cuban Missile Crisis JCC: USSR Chair: Jacob Sackett-Sanders JCC PMUNC 2015 Contents Chair Letter…………………………………………………………………...3 Introduction……………….………………………………………………….4 Topics of Concern………………………...………………….………………6 The Space Race…...……………………………....………………….....6 The Third World...…………………………………………......………7 The Eastern Bloc………………………………………………………9 The Chinese Communists…………………………………………….10 De-Stalinization and Domestic Reform………………………………11 Committee Members….……………………………………………………..13 2 JCC PMUNC 2015 Chair’s Letter Dear Delegates, It is my great pleasure to give you an early welcome to PMUNC 2015. My name is Jacob, and I’ll be your chair, helping to guide you as you take on the role of the Soviet political elites circa 1961. Originally from Wilmington, Delaware, at Princeton I study Slavic Languages and Literature. The Eastern Bloc, as well as Yugoslavia, have long been interests of mine. Our history classes and national consciousness often paints them as communist enemies, but in their own ways, they too helped to shape the modern world that we know today. While ultimately failed states, they had successes throughout their history, contributing their own shares to world science and culture, and that’s something I’ve always tried to appreciate. Things are rarely as black and white as the paper and ink of our textbooks. During the conference, you will take on the role of members of the fictional Soviet Advisory Committee on Centralization and Global Communism, a new semi-secret body intended to advise the Politburo and other major state organs. You will be given unmatched power but also faced with a variety of unique challenges, such as unrest in the satellite states, an economy over-reliant on heavy industry, and a geopolitical sphere of influence being challenged by both the USA and an emerging Communist China. -

Remembering the Sixties: a Quartet

Remembering the Sixties: A Quartet Only now, in retrospect, do I wonder what would I be like, and what would I be doing if I had been born ten years earlier or later. Leaving home and moving into the sixties wasn't quite like living through the French Revolution, but it sure explains why I took so many courses on the Romantics. And what if I had chosen to do a degree in Modern Languages at Trinity College, as I had planned, instead of going to Glendon College and doing one in English and French? Glendon, with a former diplomat, Escott Reid, as principal, was structured in terms that prefigured the Trudeau years, as a bilingual college that recruited heavily among the children of politicians and civil servants. And every year, the college pro- vided money to the students to run a major conference on a political issue. In first year I met separatists (which is how I know that René Levesque was as short as I am and that he could talk and smoke at the same time. Probably, I didn't understand a word he said.) I learned I was anglophone. In second year I met Native people for the first time in my life to talk to. I demonstrated against the Liberal White Paper introduced in 1969. (Harold Cardinal summed up its position: "The only good Indian is a non-Indian.") I learned I was white. In first year I wore miniskirts, got my hair cut at Sassoon's, and shopped the sale racks at Holt Renfrew. -

Download (PDF)

N° 3/2019 recherches & documents March 2019 Disarmament diplomacy Motivations and objectives of the main actors in nuclear disarmament EMMANUELLE MAITRE, research fellow, Fondation pour la recherche stratégique WWW . FRSTRATEGIE . ORG Édité et diffusé par la Fondation pour la Recherche Stratégique 4 bis rue des Pâtures – 75016 PARIS ISSN : 1966-5156 ISBN : 978-2-490100-19-4 EAN : 9782490100194 WWW.FRSTRATEGIE.ORG 4 BIS RUE DES PÂTURES 75 016 PARIS TÉL. 01 43 13 77 77 FAX 01 43 13 77 78 SIRET 394 095 533 00052 TVA FR74 394 095 533 CODE APE 7220Z FONDATION RECONNUE D'UTILITÉ PUBLIQUE – DÉCRET DU 26 FÉVRIER 1993 SOMMAIRE INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 5 1 – A CONVERGENCE OF PACIFIST AND HUMANITARIAN TRADITIONS ....................................... 8 1.1 – Neutrality, non-proliferation, arms control and disarmament .......................... 8 1.1.1 – Disarmament in the neutralist tradition .............................................................. 8 1.1.2 – Nuclear disarmament in a pacifist perspective .................................................. 9 1.1.1 – "Good international citizen" ..............................................................................11 1.2 – An emphasis on humanitarian issues ...............................................................13 1.2.1 – An example of policy in favor of humanitarian law ............................................13 1.2.2 – Moral, ethics and religion .................................................................................14 -

Introduction

INTRODUCTION By December 1942, when these Bulletins begin, the tide of World War II was beginning to turn against the Axis powers. The United States had been a combatant for a year, and the USSR for a year and a half. In Europe, the British and the Americans were beginning to assert mastery of the skies over the Nazi-occupied continent. In North Africa, General Montgomery had just defeated Field Marshall Rommell in the great desert battle of El Alamein; within a few months the Allies would be landing in Sicily to begin a thrust at Hitler's 'soft underbelly' in Italy. In the Soviet Union, the Nazi advance had been halted, and the catasü-ophic German defeat at Stalingrad was about to unfold. In the Pacific, the ultimately decisive naval battle of Midway had halted the Japanese advance westward in the spring, and the Americans were driving the Japanese from Guadalcanal through December and January. For Canadians, the dark days of early 1940 when Canada stood at Britain's side against a triumphant Hitler straining at the English Channel were history, replaced by a confidence that in the now globalized struggle the Allies held the ultimately winning hand. Confidence in final victory abroad did not of course obscure the terrible costs, material and human, which were still to be exacted. World War 11 was a total war, in a way in which no earlier conflict could match. The 1914-1918 war took a worse toll of Canada's soldiers, but what was most chilling about the 1939-45 struggle was to the degree to which civilian non-combatants were targeted by the awesomely lethal technology of death. -

The Limits to Influence: the Club of Rome and Canada

THE LIMITS TO INFLUENCE: THE CLUB OF ROME AND CANADA, 1968 TO 1988 by JASON LEMOINE CHURCHILL A thesis presented to the University of Waterloo in fulfilment of the thesis requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2006 © Jason Lemoine Churchill, 2006 Declaration AUTHOR'S DECLARATION FOR ELECTRONIC SUBMISSION OF A THESIS I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this thesis. This is a true copy of the thesis, including any required final revisions, as accepted by my examiners. I understand that my thesis may be made electronically available to the public. ii Abstract This dissertation is about influence which is defined as the ability to move ideas forward within, and in some cases across, organizations. More specifically it is about an extraordinary organization called the Club of Rome (COR), who became advocates of the idea of greater use of systems analysis in the development of policy. The systems approach to policy required rational, holistic and long-range thinking. It was an approach that attracted the attention of Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau. Commonality of interests and concerns united the disparate members of the COR and allowed that organization to develop an influential presence within Canada during Trudeau’s time in office from 1968 to 1984. The story of the COR in Canada is extended beyond the end of the Trudeau era to explain how the key elements that had allowed the organization and its Canadian Association (CACOR) to develop an influential presence quickly dissipated in the post- 1984 era. The key reasons for decline were time and circumstance as the COR/CACOR membership aged, contacts were lost, and there was a political paradigm shift that was antithetical to COR/CACOR ideas. -

The Gouzenko Affair and the Cold War Soviet Spies in Canada An

The Gouzenko Affair and the Cold War Soviet Spies in Canada On the evening of September 5, 1945 Igor Gouzenko, a cipher clerk for the military attaché, Colonel Nikolai Zabotin of the Soviet embassy in Ottawa, left the embassy carrying a number of secret documents. Gouzenko tried to give the documents to the Ottawa Journal and to the Minister of Justice, Louis St. Laurent, but both turned him away. Frustrated and fearful, he returned to his Somerset Street apartment on the evening of September 6 with his wife and child and appealed to his neighbors for help. One of them alerted the Ottawa City Police while another took the Gouzenko family in for the night. Meanwhile, officials from the Soviet embassy forced their way into Gouzenko's apartment. When Ottawa City Police arrived on the scene, there was an angry exchange and the Soviets left without their cipher clerk or the stolen documents. On the advice of the Undersecretary of State for External Affairs, Norman Robertson, Gouzenko was taken by the city police to RCMP headquarters on the morning of September 7 for questioning. Once there, he officially defected. More importantly, he turned over the documents that he had taken from the Soviet embassy to the RCMP. These papers proved the existence of a Soviet spy network operating inside several government departments in Canada and in the British High Commission in Ottawa. The Soviets also had a spy network in the joint Canadian-British atomic research project to obtain secret atomic information from Canada, Great Britain and the United States. -

R=Nr.3685 ,,, ,{ -- R.104TA (-{, 001

3Kcnen~lHrn 3 . ~ ,_ CCCP r=nr.3685 ,,, ,{ -- r.104TA (-{, 001 diasporiana.org.ua CENTRE FOR RESEARCH ON CANADIAN-RUSSIAN RELATIONS Unive~ty Partnership Centre I Georgian College, Barrie, ON Vol. 9 I Canada/Russia Series J.L. Black ef Andrew Donskov, general editors CRCR One-Way Ticket The Soviet Return-to-the-Homeland Campaign, 1955-1960 Glenna Roberts & Serge Cipko Penumbra Press I Manotick, ON I 2008 ,l(apyHoK OmmascbKozo siooiny KaHaOCbKozo Tosapucmsa npuHmeniB YKpai°HU Copyright © 2008 Library and Archives Canada SERGE CIPKO & GLENNA ROBERTS Cataloguing-in-Publication Data No part of this publication may be Roberts, Glenna, 1934- reproduced, stored in a retrieval system Cipko, Serge, 1961- or transmitted, in any1'0rm or by any means, without the prior written One-way ticket: the Soviet return-to consent of the publisher or a licence the-homeland campaign, 1955-1960 I from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Glenna Roberts & Serge Cipko. Agency (Access Copyright). (Canada/Russia series ; no. 9) PENUMBRA PRESS, publishers Co-published by Centre for Research Box 940 I Manotick, ON I Canada on Canadian-Russian Relations, K4M lAB I penumbrapress.ca Carleton University. Printed and bound by Custom Printers, Includes bibliographical references Renfrew, ON, Canada. and index. PENUMBRA PRESS gratefully acknowledges ISBN 978-1-897323-12-0 the financial support of the Government of Canada through the Book Publishing L Canadians-Soviet Union Industry Development Program (BPIDP) History-2oth century. for our publishing activities. We also 2. Repatriation-Soviet Union acknowledge the Government of Ontario History-2oth century. through the Ontario Media Development 3. Canadians-Soviet Union Corporation's Ontario Book Initiative. -

New Evidence on the Korean War

176 COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT BULLETIN 11 New Evidence on the Korean War Editor’s note: The documents featured in this section of the Bulletin present new evidence on the allegations that the United States used bacteriological weapons during the Korean War. In the accompanying commentaries, historian Kathryn Weathersby and scientist Milton Leitenberg (University of Maryland) provide analysis, context and interpretation of these documents. Unlike other documents published in the Bulletin, these documents, first obtained and published (in Japanese) by the Japanese newspaper Sankei Shimbun, have not been authenticated by access to the archival originals (or even photocopies thereof). The documents were copied by hand in the Russian Presidential Archive in Moscow, then typed. Though both commentators believe them to be genuine based on textual analysis, questions about the authenticity of the documents, as the commentators note, will remain until the original documents become available in the archives. Copies of the typed transcription (in Russian) have been deposited at the National Security Archive, a non-governmental research institute and repository of declassified documents based at George Washington University (Gelman Library, Suite 701; 2130 H St., NW; Washington, DC 20037; tel: 202/994-7000; fax: 202/ 994-7005) and are accessible to researchers. CWIHP welcomes the discussion of these new findings and encourages the release of the originals and additional materials on the issue from Russian, Chinese, Korean and U.S. archives. Deceiving the Deceivers: Moscow, Beijing, Pyongyang, and the Allegations of Bacteriological Weapons Use in Korea By Kathryn Weathersby n January 1998 the Japanese newspaper Sankei raised by their irregular provenance? Their style and form Shimbun published excerpts from a collection of do not raise suspicion. -

Remembering the Cuban Missile Crisis: Should We Swallow Oral History? Author(S): Mark Kramer, Bruce J

Remembering the Cuban Missile Crisis: Should We Swallow Oral History? Author(s): Mark Kramer, Bruce J. Allyn, James G. Blight and David A. Welch Reviewed work(s): Source: International Security, Vol. 15, No. 1 (Summer, 1990), pp. 212-218 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2538987 . Accessed: 18/09/2012 11:15 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to International Security. http://www.jstor.org Correspondence MarkKramer Remembering the Cuban Missile Crisis: BruceJ. Allyn, Should We Swallow Oral History? JamesG. Blight,and DavidA. Welch To the Editors: Bruce Allyn, James Blight, and David Welch should be congratulatedfor a splendid review of some of the most importantfindings from their joint researchon the Cuban missile crisis, including the conferences they helped organize in Hawk's Cay, Cam- bridge, and Moscow.' They have performed an invaluable service for both historians and political scientists. Nevertheless, the research methodology that Allyn, Blight, and Welch (henceforth AB&W)have used is not without its drawbacks.Although their work has given us a much better understanding of the Americanside of the Cuban missile crisis, I am not sure we yet have a better understanding of the Soviet side. -

H-Diplo ARTICLE REVIEW 957 18 June 2020

H-Diplo ARTICLE REVIEW 957 18 June 2020 Luc-André Brunet. “Unhelpful Fixer? Canada, the Euromissile Crisis, and Pierre Trudeau’s Peace Initiative, 1983–1984.” The International History Review 41:6 (2019): 1145-1167. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2018.1472623. https://hdiplo.org/to/AR957 Editor: Diane Labrosse | Commissioning Editor: Cindy Ewing | Production Editor: George Fujii Review by Greg Donaghy, University of Toronto here are very few episodes in Canada’s diplomatic history—and none so unsuccessful—that that have attracted the scholarly ink reserved for Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau’s controversial peace initiative at the height of the second T Cold War in the fall of 1983.1 The latest entry is Luc-André Brunet’s award-winning article, “Unhelpful Fixer? Canada, the Euromissile Crisis, and Pierre Trudeau’s Peace Initiative, 1983-1984.” Superbly researched in seven national archives, carefully argued, and presented with verve and spirit, “Unhelpful Fixer” will quite probably remain the last word on the subject for some time to come. For Brunet, the story starts in the summer of 1983, when Trudeau, already fifteen years in power, cast about for a dramatic foreign policy initiative that would restore his cratering poll numbers. Horrified by Moscow’s decision to shoot-down an errant Korean airliner over Soviet airspace on 1 September 1983, Trudeau leapt into action. Sidelining the foreign and defence policy establishment, he assembled a Task Force of mid-level officials, and asked it to cobble together a series of arms control and disarmament measures to “change the trend line” (1148) in East-West relations and reduce the brittle tensions between the United States and the USSR. -

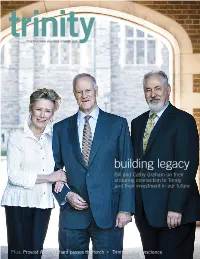

Building Legacy Bill and Cathy Graham on Their Enduring Connection to Trinity and Their Investment in Our Future

trinityTRINITY ALUMNI MAGAZINE SUMMER 2013 building legacy Bill and Cathy Graham on their enduring connection to Trinity and their investment in our future Plus: Provost Andy Orchard passes the torch • Trinity’s eco-conscience provost’smessage Trinity’s Secret Strength A farewell to a team that is PAC-ed with affection For most students, their time at Trinity simply flies by. But those Jonathan Steels, following the departure of Kelley Castle, has rede- four or five years of living and learning and growing and gaining fined the role of Dean of Students and built both community and still linger on, long after the place itself has been left behind. Over consensus. Likewise, our Registrar, Nelson De Melo, had a hard act the past six years as Provost I have been privileged to meet many to follow in Bruce Bowden, but has made his indelible mark already wonderful Men and Women of College, and hear many splen- in remaking his entire office. did stories. I write this in the wake of Reunion, that wondrous Another of the newcomers who has recruited well and widely is weekend of memories made and recalled and rekindled, and Alana Silverman: there is renewed energy and purpose in the Office friendships new and old found and further fostered. In my last of Development and Alumni Affairs, to which Alana brings fresh column as Provost, it is the thought of returning to the College vision and an alternative perspective. A consequence of all this activ- that moves me most, and makes me want to look forward, as well ity across so many departments is the increased workload of Helen as back, and to celebrate those who will run the place long after Yarish, who replaced Jill Willard, and has again through admirable this Provost has gone. -

Quoting at Random

Quoting at Random STATEMENTS ON THE TREATY ON THE NON PROLIFERATION OF NUCLEAR WEAPONS President Lyndon B. Johnson, UN-GA(XXII), 12 June 1968: "I believe that this Treaty can lead to further measures that will inhibit the senseless continuation of the arms race. I believe that it can give the world time — very precious time — to protect itself against Armageddon, and if my faith is well- founded, as I believe it is, then this Treaty will truly deserve to be recorded as the most important step towards peace since the founding of the United Nations." Mr. Alexei Kosygin, Chairman of the Council of Ministers of the USSR, at the signing of NPT, 1 July 1968: "The participation by a large number of States today in signing the Treaty is convincing proof that mutually acceptable ways and means can be found by States for solving difficult international problems of vital importance for mankind as a whole. The drawing up of the Treaty has demanded great efforts and prolonged discussions in which States with differing social systems, nuclear and non-nuclear Powers, countries large and small, advanced and developing, have all taken part. The Treaty reflects the numerous suggestions and proposals put forward by different States and takes into account the differing points of view on solving the problem of non-proliferation, yet all the States which voted for it have agreed on the main point, namely the necessity of preventing proliferation of nuclear weapons." Prime Minister Harold Wilson, United Kingdom, at the signing of NPT, 1 July 1968: "This is not a Treaty for which just two or three countries are responsible.