Sindhi Nationalism During One Unit Julien Levesque

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Centre-Province Relations, 1988-1993: a Case Study of the Punjab

Centre-Province Relations, 1988-1993: A Case Study of the Punjab A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF SOCIAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY By Syed Tahir Hussain Bukhari Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan 2016 Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Department of History Quaid-i-Azam University Islamabad, Pakistan 2016 DECLARATION I hereby declare that this thesis is the result of my individual research, and that it has not been submitted concurrently to any other university for any other degree. _____________________ Syed Tahir Hussain Bukhari DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD Approval for Thesis Submission Dated: 2016 I hereby recommend the thesis prepared under my supervision by Syed Tahir Hussain Bukhari, entitled “Centre-Province Relations, 1988-1993: A Case Study of the Punjab” in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. __________________________ Dr. Razia Sultana Supervisor DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY QUAID-I-AZAM UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD Dated: 2016 FINAL APPROVAL This is to certify that we have read the thesis submitted by Syed Tahir Hussain Bukhari, entitled “Centre-Province Relations, 1988-1993: A Case Study of the Punjab” and it is our judgment that this thesis is of sufficient standard to warrant acceptance by the Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, for the award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History. _ ____________________ -

Final Merit List of Candidates Applied for Admission in Bs Medical Laboratory

BS MEDICAL LABORATORY TECHNOLOGY (BSMLT) SESSION - 2020-2021 FINAL MERIT LIST OF CANDIDATES APPLIED FOR ADMISSION IN BS MEDICAL LABORATORY TECHNOLOGY (BSMLT) SESSION 2020-2021 LIAQUAT UNIVERSITY OF MEDICAL & HEALTH SCIENCES, JAMSHORO DISTRICT - BADIN (BS MEDICAL LABORATORY TECHNOLOGY (BSMLT) - 01 - SEAT - MERIT) Test Test Int. Total Merit Inter A / Level Test Form No. Name of Candidates Fathers Name Surname Gender DOB District Seat Marks 50% score Positon Obt 50% Year Inter% Grade No. Marks 1 4841 Habesh Kumar Veero Mal Khattri Male 1/11/2001 BADIN 2019 905 82.273 A1 719 82 41 41.136 82.136 District: BADIN - WAITING Menghwar 1496 Akash Kumar Mansingh Male 10/16/2001 BADIN 2020 913 83 A1 167 78 39 41.5 80.5 2 Bhatti 3 1215 Janvi Papoo Kumar Lohana Female 2/11/2002 BADIN 2020 863 78.455 A 894 82 41 39.227 80.227 4 3344 Bushra Muhammad Ayoub Kamboh Female 9/30/2000 BADIN 2019 835 75.909 A 490 82 41 37.955 78.955 5 1161 Chanderkant Papoo Kumar Lohana Male 3/8/2003 BADIN 2020 889 80.818 A1 503 76 38 40.409 78.409 6 3479 Bushra Amjad Amjad Ali Jat Female 4/20/2001 BADIN 2019 848 77.091 A 494 73 36.5 38.545 75.045 7 4306 Noor Ahmed Ghulam Muhammad Notkani Male 10/12/2001 BADIN 2020 874 79.455 A 1575 70 35 39.727 74.727 Muhammad Talha 2779 Hasan Nasir Rajput Male 7/21/2001 BADIN 2020 927 84.273 A1 1378 65 32.5 42.136 74.636 8 Nasir 9 3249 Vandna Dev Anand Lohana Female 3/21/2002 BADIN 2020 924 84 A1 2294 65 32.5 42 74.5 10 2231 Sanjai Eshwar Kumar Luhano Male 8/17/2000 BADIN 2020 864 78.546 A 1939 70 35 39.273 74.273 RANA RAJINDAR 3771 RANA AMAR -

Political Development, the People's Party of Pakistan and the Elections of 1970

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1973 Political development, the People's Party of Pakistan and the elections of 1970. Meenakshi Gopinath University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Gopinath, Meenakshi, "Political development, the People's Party of Pakistan and the elections of 1970." (1973). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2461. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2461 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FIVE COLLEGE DEPOSITORY POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT, THE PEOPLE'S PARTY OF PAKISTAN AND THE ELECTIONS OF 1970 A Thesis Presented By Meenakshi Gopinath Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS June 1973 Political Science POLITICAL DEVELOPMENT, THE PEOPLE'S PARTY OF PAKISTAN AND THE ELECTIONS OF 1970 A Thesis Presented By Meenakshi Gopinath Approved as to style and content hy: Prof. Anwar Syed (Chairman of Committee) f. Glen Gordon (Head of Department) Prof. Fred A. Kramer (Member) June 1973 ACKNOWLEDGMENT My deepest gratitude is extended to my adviser, Professor Anwar Syed, who initiated in me an interest in Pakistani poli- tics. Working with such a dedicated educator and academician was, for me, a totally enriching experience. I wish to ex- press my sincere appreciation for his invaluable suggestions, understanding and encouragement and for synthesizing so beautifully the roles of Friend, Philosopher and Guide. -

Shahmurad Sugar Mills Limited

SHAHMURAD SUGAR MILLS LIMITED Half Yearly Results for the period 1st October 2019 to 31st March, 2020 SHAHMURAD SUGAR MILLS LTD. COMPANY INFORMATION BOARD OF DIRECTORS MR. ZIA ZAKARIA Managing Director & CEO MR. ABDUL AZIZ AYOOB MR. NOOR MOHAMMAD ZAKARIA MRS. SANOBAR HAMID ZAKARIA MR. NAEEM AHMED SHAFI Independent Director MR. KHURRAM AFTAB Independent Director BOARD AUDIT COMMITTEE MR. NAEEM AHMED SHAFI Chairman MR. NOOR MOHAMMAD ZAKARIA Member MRS. SANOBAR HAMID ZAKARIA Member HUMAN RESOURCE AND REMUNERATION COMMITTEE MR. KHURRAM AFTAB Chairman MR.NOOR MOHAMMAD ZAKARIA Member MR. ZIA ZAKARIA Member CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER MR. ZAID ZAKARIA COMPANY SECRETARY MR. MOHAMMAD YASIN MUGHAL FCMA AUDITORS M/s. KRESTON HYDER BHIMJI & CO. Chartered Accountants LEGAL ADVISOR MR. IRFAN Advocate REGISTERED OFFICE 96-A, SINDHI MUSLIM HOUSING SOCIETY, KARACHI-74400 Tel: 34550161-63 Fax: 34556675 FACTORY JHOK SHARIF, TALUKA MIRPUR BATHORO, DISTRICT SUJAWAL (SINDH) REGISTRAR & SHARES REGISTRATION OFFICE M/S C & K MANAGEMENT ASSOCIATES (PVT) LTD. 404-TRADE TOWER, ABDULLAH HAROON ROAD, NEAR METROPOLE HOTEL, KARACHI - 75530 WEBSITE www.shahmuradsugar.co 1 SHAHMURAD SUGAR MILLS LTD. DIRECTORS' REPORT Dear Members Asslamu Alaikum On behalf of Board, I take the opportunity to present before you with great pleasure the un-audited financial statements of your company for the period ended March 31, 2020. The financial statements have been reviewed by the Auditors as required under the Code of Corporate Governance. Salient features of production and Financial Statements -

UNIVERSITA CA'foscari VENEZIA CHAUKHANDI TOMBS a Peculiar

UNIVERSITA CA’FOSCARI VENEZIA Dottorato di Ricerca in Lingue Culture e Societa` indirizzo Studi Orientali, XXII ciclo (A.A. 2006/2007 – A. A. 2009/2010) CHAUKHANDI TOMBS A Peculiar Funerary Memorial Architecture in Sindh and Baluchistan (Pakistan) TESI DI DOTTORATO DI ABDUL JABBAR KHAN numero di matricola 955338 Coordinatore del Dottorato Tutore del Dottorando Ch.mo Prof. Rosella Mamoli Zorzi Ch.mo Prof. Gian Giuseppe Filippi i Chaukhandi Tombs at Karachi National highway (Seventeenth Century). ii AKNOWLEDEGEMENTS During my research many individuals helped me. First of all I would like to offer my gratitude to my academic supervisor Professor Gian Giuseppe Filippi, Professor Ordinario at Department of Eurasian Studies, Universita` Ca`Foscari Venezia, for this Study. I have profited greatly from his constructive guidance, advice, enormous support and encouragements to complete this dissertation. I also would like to thank and offer my gratitude to Mr. Shaikh Khurshid Hasan, former Director General of Archaeology - Government of Pakistan for his valuable suggestions, providing me his original photographs of Chuakhandi tombs and above all his availability despite of his health issues during my visits to Pakistan. I am also grateful to Prof. Ansar Zahid Khan, editor Journal of Pakistan Historical Society and Dr. Muhammad Reza Kazmi , editorial consultant at OUP Karachi for sharing their expertise with me and giving valuable suggestions during this study. The writing of this dissertation would not be possible without the assistance and courage I have received from my family and friends, but above all, prayers of my mother and the loving memory of my father Late Abdul Aziz Khan who always has been a source of inspiration for me, the patience and cooperation from my wife and the beautiful smile of my two year old daughter which has given me a lot courage. -

Sindhi Community – Shiv Sena

Refugee Review Tribunal AUSTRALIA RRT RESEARCH RESPONSE Research Response Number: IND30284 Country: India Date: 4 July 2006 Keywords: India – Maharashtra – Sindhi Community – Shiv Sena This response was prepared by the Country Research Section of the Refugee Review Tribunal (RRT) after researching publicly accessible information currently available to the RRT within time constraints. This response is not, and does not purport to be, conclusive as to the merit of any particular claim to refugee status or asylum. Questions 1. Is there any independent information about any current ill-treatment of Sindhi people in Maharashtra state? 2. Is there any information about the authorities’ position on any ill-treatment of Sindhi people? RESPONSE 1. Is there any independent information about any current ill-treatment of Sindhi people in Maharashtra state? Executive Summary Information available on Sindhi websites, in press reports and in academic studies suggests that, generally speaking, the Sindhi community in Maharashtra state are not ill-treated. Most writers who address the situation of Sindhis in Maharashtra generally concern themselves with the social and commercial success which the Sindhis have achieved in Mumbai (where the greater part of the Sindh’s Hindu populace relocated after the partition of India and Pakistan). One news article was located which reported that the Sindhi community had been targeted for extortion, along with other “mercantile communities”, by criminal networks affiliated with Maharashtra state’s Sihiv Sena organisation. -

Son of the Desert

Dedicated to Mohtarma Benazir Bhutto Shaheed without words to express anything. The Author SONiDESERT A biography of Quaid·a·Awam SHAHEED ZULFIKAR ALI H By DR. HABIBULLAH SIDDIQUI Copyright (C) 2010 by nAfllST Printed and bound in Pakistan by publication unit of nAfllST Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto/Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Archives. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. First Edition: April 2010 Title Design: Khuda Bux Abro Price Rs. 650/· Published by: Shaheed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto/ Shaheed Benazir Bhutto Archives 4.i. Aoor, Sheikh Sultan Trust, Building No.2, Beaumont Road, Karachi. Phone: 021-35218095-96 Fax: 021-99206251 Printed at: The Time Press {Pvt.) Ltd. Karachi-Pakistan. CQNTENTS Foreword 1 Chapter: 01. On the Sands of Time 4 02. The Root.s 13 03. The Political Heritage-I: General Perspective 27 04. The Political Heritage-II: Sindh-Bhutto legacy 34 05. A revolutionary in the making 47 06. The Life of Politics: Insight and Vision· 65 07. Fall out with the Field Marshal and founding of Pakistan People's Party 108 08. The state dismembered: Who is to blame 118 09. The Revolutionary in the saddle: New Pakistan and the People's Government 148 10. Flash point.s and the fallout 180 11. Coup d'etat: tribulation and steadfasmess 197 12. Inside Death Cell and out to gallows 220 13. Home they brought the warrior dead 229 14. -

Makers-Of-Modern-Sindh-Feb-2020

Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honor MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh SMIU Press Karachi Alma-Mater of Quaid-e-Azam Mohammad Ali Jinnah Sindh Madressatul Islam University, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000 Pakistan. This book under title Sindh Madressah’s Roll of Honour MAKERS OF MODERN SINDH Lives of 25 Luminaries Written by Professor Dr. Muhammad Ali Shaikh 1st Edition, Published under title Luminaries of the Land in November 1999 Present expanded edition, Published in March 2020 By Sindh Madressatul Islam University Price Rs. 1000/- SMIU Press Karachi Copyright with the author Published by SMIU Press, Karachi Aiwan-e-Tijarat Road, Karachi-74000, Pakistan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any from or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passage in a review Dedicated to loving memory of my parents Preface ‘It is said that Sindh produces two things – men and sands – great men and sandy deserts.’ These words were voiced at the floor of the Bombay’s Legislative Council in March 1936 by Sir Rafiuddin Ahmed, while bidding farewell to his colleagues from Sindh, who had won autonomy for their province and were to go back there. The four names of great men from Sindh that he gave, included three former students of Sindh Madressah. Today, in 21st century, it gives pleasure that Sindh Madressah has kept alive that tradition of producing great men to serve the humanity. -

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts

Honour Killing in Sindh Men's and Women's Divergent Accounts Shahnaz Begum Laghari PhD University of York Women’s Studies March 2016 Abstract The aim of this project is to investigate the phenomenon of honour-related violence, the most extreme form of which is honour killing. The research was conducted in Sindh (one of the four provinces of Pakistan). The main research question is, ‘Are these killings for honour?’ This study was inspired by a need to investigate whether the practice of honour killing in Sindh is still guided by the norm of honour or whether other elements have come to the fore. It is comprised of the experiences of those involved in honour killings through informal, semi- structured, open-ended, in-depth interviews, conducted under the framework of the qualitative method. The aim of my thesis is to apply a feminist perspective in interpreting the data to explore the tradition of honour killing and to let the versions of the affected people be heard. In my research, the women who are accused as karis, having very little redress, are uncertain about their lives; they speak and reveal the motives behind the allegations and killings in the name of honour. The male killers, whom I met inside and outside the jails, justify their act of killing in the name of honour, culture, tradition and religion. Drawing upon interviews with thirteen women and thirteen men, I explore and interpret the data to reveal their childhood, educational, financial and social conditions and the impacts of these on their lives, thoughts and actions. -

Historical Sketch of Peasant Activism: Tracing Emancipatory Political Strategies of Peasant Activists of Sindh

International Journal Humanities and Social Sciences (IJHSS) ISSN (P): 2319-393X; ISSN(E): 2319-3948 Vol. 3, Issue 5, Sep 2014, 23-42 © IASET HISTORICAL SKETCH OF PEASANT ACTIVISM: TRACING EMANCIPATORY POLITICAL STRATEGIES OF PEASANT ACTIVISTS OF SINDH GHULAM HUSSAIN 1 & ANWAAR MOHYUDDIN 2 1MPhil Scholar, Department of Anthropology, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan 2 Lecturer, Department of Anthropology, Quaid-i-Azam University, Islamabad, Pakistan ABSTRACT Peasant activism in Sindh is very diverse and has its own typical history. Temporally, it has been focused on contextual issues that demand more than just land reforms. Peasant activists have, over the years, pursued roughly articulated, expedient and highly diverse agendas that are enacted by the mix of civil society activists, NGOs and ethnic peasant activists. In this article, which is the result of ethnographic study and the analysis of secondary ethnographic and historical data, effort has been made to trace the formation of peasantivist agendas and strategies in Sindh, particularly tracing it from the peasant struggle of Shah Inayat in 17 th century. The introduction of exploitative Batai system during British rule, the consequent institutionalization of sharecropping, establishment of Hari Committee in 1930s, the launching of Batai Tehreek and Elati Tehreek have been traced in relation to shifting peasantivist agendas. Failure of peasant activists to bring about substantive land reforms and the recent process of NGO-ising of peasant activism, have been analyzed vis-à-vis historical past. KEYWORDS: Peasant Activism, Peasant Movements, N.G.Os INTRODUCTION In this study the genesis of exploitation in peasant communities of Sindh has been elaborated, and the historical analysis of some of the important peasant struggles, rebels, and movements have been done to understand where peasants and peasant activist in Sindh stands now. -

Politics of Sindh Under Zia Government an Analysis of Nationalists Vs Federalists Orientations

POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan POLITICS OF SINDH UNDER ZIA GOVERNMENT AN ANALYSIS OF NATIONALISTS VS FEDERALISTS ORIENTATIONS A Thesis Doctor of Philosophy By Amir Ali Chandio 2009 Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Chaudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University Multan Dedicated to: Baba Bullay Shah & Shah Abdul Latif Bhittai The poets of love, fraternity, and peace DECLARATION This thesis is the result of my own investigations, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged by giving explicit references. A bibliography is appended. This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………………….( candidate) Date……………………………………………………………………. CERTIFICATES This is to certify that I have gone through the thesis submitted by Mr. Amir Ali Chandio thoroughly and found the whole work original and acceptable for the award of the degree of Doctorate in Political Science. To the best of my knowledge this work has not been submitted anywhere before for any degree. Supervisor Professor Dr. Ishtiaq Ahmed Choudhry Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan Chairman Department of Political Science & International Relations Bahauddin Zakariya University, Multan, Pakistan. ABSTRACT The nationalist feelings in Sindh existed long before the independence, during British rule. The Hur movement and movement of the separation of Sindh from Bombay Presidency for the restoration of separate provincial status were the evidence’s of Sindhi nationalist thinking. -

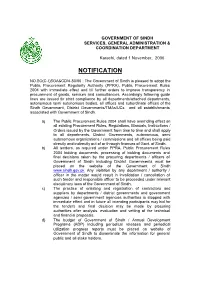

Notification

GOVERNMENT OF SINDH SERVICES, GENERAL ADMINISTRATION & COORDINATION DEPARTMENT Karachi, dated 1 November, 2006 NOTIFICATION NO.SO(C-I)SGA&CD/4-80/06 : The Government of Sindh is pleased to adopt the Public Procurement Regularity Authority (PPRA), Public Procurement Rules 2004 with immediate effect and till further orders to improve transparency in procurement of goods, services and consultancies. Accordingly following guide lines are issued for strict compliance by all departments/attached departments, autonomous semi autonomous bodies, all offices and subordinate offices of the Sindh Government, District Governments/TMAs/UCs and all establishments associated with Government of Sindh. a) The Public Procurement Rules 2004 shall have overriding effect on all existing Procurement Rules, Regulations, Manuals, Instructions / Orders issued by the Government from time to time and shall apply to all departments, District Governments, autonomous, semi autonomous organizations / commissions and all offices being paid directly and indirectly out of or through finances of Govt. of Sindh. b) All tenders, as required under PPRA, Public Procurement Rules 2004 bidding documents, processing of bidding documents and final decisions taken by the procuring departments / officers of Government of Sindh including District Governments must be placed on the website of the Government of Sindh www.sindh.gov.pk Any violation by any department / authority / officer in the matter would result in invalidation / cancellation of such tender and responsible officer to be proceeded under relevant disciplinary laws of the Government of Sindh. c) The practice of enlisting and registration of contractors and suppliers by departments / district governments and government agencies / semi government agencies authorities is stopped with immediate effect and in future all intending participants may bid for the tenders and final decision may be made by procuring authorities after analysis, evaluation and vetting of the technical and financial proposals.