“This Video Is Unavailable” “This Video Is Unavailable” Analyzing Copyright Takedown of User-Generated Content on Youtube

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teenie Weenie in a Too Big World: a Story for Fearful Children Free

FREE TEENIE WEENIE IN A TOO BIG WORLD: A STORY FOR FEARFUL CHILDREN PDF Margot Sunderland,Nicky Hancock,Nicky Armstrong | 32 pages | 03 Oct 2003 | Speechmark Publishing Ltd | 9780863884603 | English | Bicester, Oxon, United Kingdom ບິ ກິ ນີ - ວິ ກິ ພີ ເດຍ A novelty song is a type of song built upon some form of novel concept, such as a gimmicka piece of humor, or a sample of popular culture. Novelty songs partially overlap with comedy songswhich are more explicitly based on humor. Novelty songs achieved great popularity during the s and s. Novelty songs are often a parody or humor song, and may apply to a current event such as a holiday or a fad such as a dance or TV programme. Many use unusual Teenie Weenie in a Too Big World: A Story for Fearful Children, subjects, sounds, or instrumentation, and may not even be musical. It is based on their achievement Teenie Weenie in a Too Big World: A Story for Fearful Children a UK number-one single with " Doctorin' the Tardis ", a dance remix mashup of the Doctor Who theme music released under the name of 'The Timelords. Novelty songs were a major staple of Tin Pan Alley from its start in the late 19th century. They continued to proliferate in the early years of the 20th century, some rising to be among the biggest hits of the era. We Have No Bananas "; playful songs with a bit of double entendre, such as "Don't Put a Tax on All the Beautiful Girls"; and invocations of foreign lands with emphasis on general feel of exoticism rather than geographic or anthropological accuracy, such as " Oh By Jingo! These songs were perfect for the medium of Vaudevilleand performers such as Eddie Cantor and Sophie Tucker became well-known for such songs. -

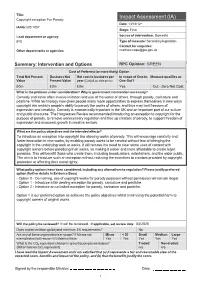

Copyright Exception for Parody Date: 13/12/12* IA No: BIS 1057 Stage: Final

Title: Impact Assessment (IA) Copyright exception For Parody Date: 13/12/12* IA No: BIS 1057 Stage: Final Lead department or agency: Source of intervention: Domestic IPO Type of measure: Secondary legislation Contact for enquiries: Other departments or agencies: [email protected] Summary: Intervention and Options RPC Opinion: GREEN Cost of Preferred (or more likely) Option Total Net Present Business Net Net cost to business per In scope of One-In, Measure qualifies as Value Present Value year (EANCB on 2009 prices) One-Out? £0m £0m £0m Yes Out - Zero Net Cost What is the problem under consideration? Why is government intervention necessary? Comedy and satire often involve imitation and use of the works of others, through parody, caricature and pastiche. While technology now gives people many more opportunities to express themselves in new ways copyright law restricts people's ability to parody the works of others, and thus may limit freedom of expression and creativity. Comedy is economically important in the UK and an important part of our culture and public discourse. The Hargreaves Review recommended introducing an exception to copyright for the purpose of parody, to remove unnecessary regulation and free up creators of parody, to support freedom of expression and economic growth in creative sectors. What are the policy objectives and the intended effects? To introduce an exception into copyright law allowing works of parody. This will encourage creativity and foster innovation in new works, by enabling parody works to be created without fear of infringing the copyright in the underlying work or works. It will remove the need to clear some uses of content with copyright owners before parodying their works, so making it easier and more affordable to create legal parodies. -

"WEIRD AL" YANKOVIC: POLKAS, PARODIES and the POWER of SATIRE by Chuck Miller Originally Published in Goldmine #514

"WEIRD AL" YANKOVIC: POLKAS, PARODIES AND THE POWER OF SATIRE By Chuck Miller Originally published in Goldmine #514 Al Yankovic strapped on his accordion, ready to perform. All he had to do was impress some talent directors, and he would be on The Gong Show, on stage with Chuck Barris and the Unknown Comic and Jaye P. Morgan and Gene Gene the Dancing Machine. "I was in college," said Yankovic, "and a friend and I drove down to LA for the day, and auditioned for The Gong Show. And we did a song called 'Mr. Frump in the Iron Lung.' And the audience seemed to enjoy it, but we never got called back. So we didn't make the cut for The Gong Show." But while the Unknown Co mic and Gene Gene the Dancing Machine are currently brain stumpers in 1970's trivia contests, the accordionist who failed the Gong Show taping became the biggest selling parodist and comedic recording artist of the past 30 years. His earliest parodies were recorded with an accordion in a men's room, but today, he and his band have replicated tracks so well one would think they borrowed the original master tape, wiped off the original vocalist, and superimposed Yankovic into the mix. And with MTV, MuchMusic, Dr. Demento and Radio Disney playing his songs right out of the box, Yankovic has reached a pinnacle of success and longevity most artists can only imagine. Alfred Yankovic was born in Lynwood, California on October 23, 1959. Seven years later, his parents bought him an accordion for his birthday. -

Parody and Pastiche

Evaluating the Impact of Parody on the Exploitation of Copyright Works: An Empirical Study of Music Video Content on YouTube Parody and Pastiche. Study I. January 2013 Kris Erickson This is an independent report commissioned by the Intellectual Property Office (IPO) Intellectual Property Office is an operating name of the Patent Office © Crown copyright 2013 2013/22 Dr. Kris Erickson is Senior Lecturer in Media Regulation at the Centre ISBN: 978-1-908908-63-6 for Excellence in Media Practice, Bournemouth University Evaluating the impact of parody on the exploitation of copyright works: An empirical study of music (www.cemp.ac.uk). E-mail: [email protected] video content on YouTube Published by The Intellectual Property Office This is the first in a sequence of three reports on Parody & Pastiche, 8th January 2013 commissioned to evaluate policy options in the implementation of the Hargreaves Review of Intellectual Property & Growth (2011). This study 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 presents new empirical data about music video parodies on the online © Crown Copyright 2013 platform YouTube; Study II offers a comparative legal review of the law of parody in seven jurisdictions; Study III provides a summary of the You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the findings of Studies I & II, and analyses their relevance for copyright terms of the Open Government Licence. To view policy. this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov. uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or email: [email protected] The author is grateful for input from Dr. -

Fair Use Avoidance in Music Cases Edward Lee Chicago-Kent College of Law, [email protected]

Boston College Law Review Volume 59 | Issue 6 Article 2 7-11-2018 Fair Use Avoidance in Music Cases Edward Lee Chicago-Kent College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Edward Lee, Fair Use Avoidance in Music Cases, 59 B.C.L. Rev. 1873 (2018), https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol59/iss6/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FAIR USE AVOIDANCE IN MUSIC CASES EDWARD LEE INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1874 I. FAIR USE’S RELEVANCE TO MUSIC COMPOSITION ................................................................ 1878 A. Fair Use and the “Borrowing” of Copyrighted Content .................................................. 1879 1. Transformative Works ................................................................................................. 1879 2. Examples of Transformative Works ............................................................................ 1885 B. Borrowing in Music Composition ................................................................................... -

Being Al Yankovic

gCttil},g ,I},S'6C hJ.S ~efr6r&eSS' hJe86 by Jeff Bliss ~ wanted to write the "Weird AI" persona that has and fellow consummate "Boy, isn't earned him near-cult status and students used to do. No breaking Weird Al Yankovic really record sales in the millions. into funny songs about "SLO weird?" story, penning a Town." Just a calm, cool, and humorous' account of the Cal Poly ~of76eCof76;rb8 collected Yankovic taking it all architecture alumnus who has The limousine carrying in. (Later, however, he tells his gained more recognition for his Yankovic and his assistant wends appreciative audience at the music parodies than for any its way through downtown San Performing Arts Center on architectural renderings. Luis Obispo. Curled up in the campus, "Playing here brings back I discovered, however, that corner of the cavernous back a lot of memories on stage, in music passenger seat, Yankovic, 40, like licking the walls of videos, in sports his trademark slip-on tennis Bubble Gum Alley.") films, shoes, a pair of black pants, and The two-time and on a lime-green pullover shirt. As Grammy-winning television, the car passes the Marsh Street Yankovic, back at Alfred storefronts, he waxes nostalgic. Cal Poly for only the Mathew "When I was going to Cal second time since Yankovic's Poly, [San Luis] wasn't as tidy," graduating, isn't just (ARCH '80) he says Wistfully. "It had its funny riding around in the reputation for quirks and character to it. Like the back of a big, fancy manic craziness ['uniquely' decorated] bathrooms car. -

Jessica Getman, Brooke Mccorkle, and Evan Ware (New York: Routledge, 2020)

CURRENT POSITION JESSICA GETMAN ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF MUSICOLOGY/ETHNOMUSICOLOGY CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, SAN BERNARDINO FILM MUSIC ugAugust 2020– AMERICAN MUSIC MUSIC EDITIONS EDUCATION [email protected] PHD HISTORICAL MUSICOLOGY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, ANN ARBOR, 2015 Dissertation: “MUSIC, RACE, AND GENDER IN THE ORIGINAL SERIES OF STAR TREK (1966–1969)” Committee: Mark Clague (chair), Christi-Anne Castro, Caryl Flinn, Charles Garrett, Neil Lerner, James Wierzbicki Secondary Fields: American Music, Baroque Music, Ethnomusicology Certificates: Screen Arts and Cultures; CRLT Graduate Teacher Certificate MM MUSICOLOGY AND HISTORICAL PERFORMANCE BOSTON UNIVERSITY, 2008 Thesis: “THE ‘AIR DE JOCONDE’: A SURVEY OF A POPULAR FRENCH TIMBRE” BA MUSIC (oboe) CALIFORNIA POLYTECHNIC STATE UNIVERSITY, SAN LUIS OBISPO, 2002 RESEARCH INTERESTS Music in film, television, digital media, and video games Music and sound in science fiction film and television Musical manuscripts, editions, and textual criticism Cultural politics and identity in music George and Ira Gershwin Fan and amateur musical practices Historical performance (17th- and 18th-century) PUBLICATIONS 2019 “Gershwin in Hollywood,” in The Cambridge Companion to George Gershwin, ed. Anna Celenza (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019). 2019 “Audiences,” in SAGE Encyclopedia of Music and Culture, ed. Janet Sturman (Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc., 2019). 2018 Media Review: Kyle Dixon and Michael Stein, Stranger Things, Vol. 1 and Vol. 2 (2016) in Journal of the Society for American Music 12:4 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018). 2018 Book Review: Stanley C. Pelkey II and Anthony Bushard, Anxiety Muted: American Film Music in a Suburban Age (2015) in Journal of the Society for American Music 12:3 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2018). -

UCSB Mcnair Scholars Research Journal

UCSB McNair Scholars Research Journal UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SANTA BARBARA 2011 Volume 1 The UCSB McNair Scholars Research Journal University of California, Santa Barbara 2011 • Volume 1 NON-DISCRIMINATION STATEMENT The University of California, in accordance with applicable Federal and State law and University policy, does not discriminate on the basis of race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity, pregnancy, physical or mental disability, medical condition (cancer related or genetic characteristics), ancestry, marital status, age, sexual orientation, citizenship, or service in the uniformed service 2. The University also prohibits sexual harassment. This nondiscrimination policy covers admission, access, and treatment in University programs and activities. Please direct inquiries to: Professor Maria Herrera-Sobek Associate Vice Chancellor for Diversity, Equity and Academic Policy 5105 Cheadle Hall [email protected] Ricardo Alcaino Director and Title IX Officer, Office of Equal Opportunity & Sexual Harassment 3217 Phelps Hall [email protected] Cover Photo: Tony Mastres/UCSB Photo Services ii The UCSB McNair Scholars Research Journal MCNAIR PROGRAM STAFF Principal Investigators Dean Melvin Oliver Dean of Social Sciences Dr. Beth E. Schneider Professor of Sociology Program Director Dr. Beth E. Schneider Assistant Director Monique Limon Program Coordinator Micaela Morgan Graduate Mentor Carlos Jimenez Bernadette Gailliard Writing Consultant Dr. Ellen Broidy Journal Editors Dr. Beth E. Schneider Dr. Ellen Broidy iii The UCSB McNair Scholars Research Journal THE UCSB MCNAIR SCHOLARS RESEARCH JOURNAL 2011 • Volume 1 Table of Contents McNair Program Staff iii Table of Contents iv Letter from EVC vii Letter from Dean viii Letter from Program Director x Letter from Journal Editors xii Brianna Jones 14 Effects of pH and Temperature on Fertilization and Early Development in the Sea Urchin, Lytechinus pictus UCSB Mentor: Dr. -

Pronouncing Dictionary and Condensed Encyclopedia of Musical

i ML - i| I ii i « i| ii >it -'ilii 1 1 i lri . *'*'J''^^ wpili^^tiiim^ip m|»4i iftMt pqi. H I 444ii(l^W^ tiwS>^rtiii?n'i>,..,... , . 100 wU mm M M M , ;M42 ^ i iw riB ^>hfcWW*»««w<ffH^ liiUJfd'^iiww^wW'iUiirii Wy ^^iW iiwwyiitjtw iiiaJii Vrtiw»«*ww»n K %««wWwi*Kif= !i I - ' 'l ' 'l J..U. .m. ! ..JU! l?l' ff.'l ! ^Ktiifiii iiiaii«iiiiriiiiitiiiiiriWnriiiiiriiiiiiii»iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiriminiiiMiimiii iiiniMiiiwim ' .". " iSSaSSaMiSBS i!Si.iM„., ,.,l.'rifrf^.'',f|f Dl" . IIB BOUGHT WITH THE INCOME FROM THE SAGE ENDOWMENT FUND THE GIFT OF BenrQ W. Sage 1891 AjmimXIOJSIC u//4/m Cornell University Library ML 100.M42 3 1924 022 408 607 Cornell University Library The original of tiiis book is in tine Cornell University Library. There are no known copyright restrictions in the United States on the use of the text. http://www.archive.org/details/cu31924022408607 : PRONOUNCING DICTIONARY Condensed Encyclopedia MUSICAL TERMS, INSTRUMENTS, COMPOSERS, AND IMPORTANT WORKS. BY W. S. B. MATHEWS. PHILADELPHIA THEODORE PRESSER 1895. COPYRIGHT, 1880. W. S. B. MATHEWS, CHICAGO. Press of Wm. F. Fell & Oo, 1220-24 SANSOM STREET, PHILADELPHIA. ;;; DICTIOI^rAEY. or (Ital. prep.) A, Ab, from, of ; also name of a A capriccio (Ital. cS-prXt'-zK). At caprice; pitch. at pleasure. > Abbreviations. These are the more usual. Accelerando (Ital. St-tshal-a-rSn'-do). Ac- Look for definitions under the words them- celerating ; gradually hastening the time. selves. Accent, an emphasis or stress upon particular Accel.y for accelerando ; Accomp.^ Accom- notes or chords for the purpose of rendering pagnement ; Adgo, or Ado.^ Adagio; ad the meaning of a passage intelligible. -

Quotation and Parody

Title: Impact Assessment (IA) Copyright exception For Parody IA No: BIS 1057 Date: 13/12/12* Lead department or agency: Stage: Final IPO Source of intervention: Domestic Other departments or agencies: Type of measure: Secondary legislation Contact for enquiries: [email protected] Summary: Intervention and Options RPC Opinion: Green Cost of Preferred (or more likely) Option Total Net Present Business Net Net cost to business per In scope of One-In, Measure qualifies as Value Present Value year (EANCB on 2009 prices) One-Out? £0m £0m £0m Yes Out - Zero Net Cost What is the problem under consideration? Why is government intervention necessary? Comedy and satire often involve imitation and use of the works of others, through parody, caricature and pastiche. While technology now gives people many more opportunities to express themselves in new ways copyright law restricts people's ability to parody the works of others, and thus may limit freedom of expression and creativity. Comedy is economically important in the UK and an important part of our culture and public discourse. The Hargreaves Review recommended introducing an exception to copyright for the purpose of parody, to remove unnecessary regulation and free up creators of parody, to support freedom of expression and economic growth in creative sectors. What are the policy objectives and the intended effects? To introduce an exception into copyright law allowing works of parody. This will encourage creativity and foster innovation in new works, by enabling parody works to be created without fear of infringing the copyright in the underlying work or works. It will remove the need to clear some uses of content with copyright owners before parodying their works, so making it easier and more affordable to create legal parodies. -

Conference Programme with Abstracts (Updated: 26 July 2013)

International Association of Music Libraries, Archives and Documentation Centres (IAML) Conference Programme with abstracts (updated: 26 July 2013) Saturday, 27 July 9.00–13.00 IAML Board meeting Board members only 14.00–17.00 IAML Board meeting Board members only Sunday, 28 July 10.00–11.30 Ad Hoc Committee on Electronic Voting Working meeting (closed) Chair: Roger Flury (President, IAML) 14.00–16.30 IAML Council: 1st session All IAML members are cordially invited to attend the two Council sessions. The 2nd session will take place on Thursday at 16.00 Chair: Roger Flury (President, IAML) 19.30 Opening reception City Hall Monday, 29 July IAML Vienna 2013 – Conference Programme with abstracts (updated: 26 July 2013) Monday, 29 July 9.00–10.30 Opening session Announcements from the Conference organizers Music libraries in Vienna Strauss autographs – sources for research and musical interpretation Abstract: The Vienna City Library is holding by far the world's largest collection of manuscripts and printed material pertaining to the fabled Strauss family (Johann I-III, Josef, Eduard). Centerpiece is the collection of holographic music manuscripts. Treasured across the world, they are, however, not to be regarded as mere 'trophies', but provide key information for the understanding of the biographies of the said composers and their creative output. The presentation is to highlight some of the most telling examples. Speaker: Thomas Aigner (Wienbibliothek im Rathaus, Wien) The Archives, the Library and the Collections of the ‘Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Wien’ Speaker: Otto Biba (Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, Wien) The Imperial Hofmusikkapelle of Vienna and its traces in the Music Department of the Austrian National Library Abstract: The year 1498 is regarded as the founding year of the Imperial Court Chapel of Vienna, when Emperor Maximilian I. -

Copycats at Work and Play: Aura, Imitation, and Automation in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction

Copycats at Work and Play: Aura, Imitation, and Automation in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction A Proposal for a Summer 2017 LARC Research Community Grant Kevin Alexander Mike Chasar Eli Kerry Owen Netzer Abigail Susik Hailee Vandiver In his famous 1935 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” Walter Benjamin argues for how modern modes of technical reproduction have affected the “aura” of originality that in earlier times lent art objects a singular cultural authority. Substituting the “unique existence” of the art object with “a plurality of copies,” he contends, diminishes the mystique of art and, in making art broadly available to the public, results in new modes of perception, new publics, and new types of politics. Benjamin’s ideas seem ever more relevant to artists and scholars today, especially as we can now look back on more than a century of art and popular expression anchored in or in dialogue with a copycat aesthetic fueled in large part by the proliferation and increasing accessibility of reproduction technologies culminating in the digital technologies of our current day. Via typewriters, stenography, photography, film, and song performances in live, audio, video, digital, and karaoke contexts, artists of all stripes in the long twentieth century have orchestrated the effects of originality, imitation, and automation to copy their own and others’ work and thereby explore the possibilities and perils of art in the age of mechanical reproduction. In this research community, Professors Chasar (English) and Susik (Art History) will be joined by students Kevin Alexander (English Creative Writing), Eli Kerry (English and Film), Owen Copycats at Work and Play — Summer 2017 LARC Proposal — 1 Netzer (English), Hailee Vandiver (English literature) to study and employ modes of artistic creation engaging the long history of mechanical reproduction that Benjamin helps bring into view.