Copyright and the Economic Effects of Parody: an Empirical Study of Music Videos on the Youtube Platform, and an Assessment of Regulatory Options

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Garage Zine Scionav.Com Vol. 3 Cover Photography: Clayton Hauck

GARAGE ZINE SCIONAV.COM VOL. 3 COVER PHOTOGRAPHY: CLAYTON HAUCK STAFF Scion Project Manager: Jeri Yoshizu, Sciontist Editor: Eric Ducker Creative Direction: Scion Art Director: malbon Production Director: Anton Schlesinger Contributing Editor: David Bevan Assistant Editor: Maud Deitch Graphic Designers: Nicholas Acemoglu, Cameron Charles, Kate Merritt, Gabriella Spartos Sheriff: Stephen Gisondi CONTRIBUTORS Writer: Jeremy CARGILL Photographers: Derek Beals, William Hacker, Jeremy M. Lang, Bryan Sheffield, REBECCA SMEYNE CONTACT For additional information on Scion, email, write or call. Scion Customer Experience 19001 S. Western Avenue Company references, advertisements and/ Mail Stop WC12 or websites listed in this publication are Torrance, CA 90501 not affiliated with Scion, unless otherwise Phone: 866.70.SCION noted through disclosure. Scion does not Fax: 310.381.5932 warrant these companies and is not liable for Email: Email us through the contact page their performances or the content on their located on scion.com advertisements and/or websites. Hours: M-F, 6am-5pm PST Online Chat: M-F, 6am-6pm PST © 2011 Scion, a marque of Toyota Motor Sales U.S.A., Inc. All rights reserved. Scion GARAGE zine is published by malbon Scion and the Scion logo are trademarks of For more information about MALBON, contact Toyota Motor Corporation. [email protected] 00430-ZIN03-GR SCION A/V SCHEDULE JUNE Scion Garage 7”: Cola Freaks/Digital Leather (June 7) Scion Presents: Black Lips North American Tour The Casbah in San Diego, CA (June 9) Velvet Jones -

Found Footage Experience. Pratictices of Cinematic Re-Use and Forms of Contemporary Film

Found Footage Experience. Pratictices of cinematic re-use and forms of contemporary film edited by Rossella Catanese (University of Udine) and Giacomo Ravesi (Roma Tre University) In contemporary visual culture, the polysemy of cinematographic language finds its emblematic manifestation in the various paradigms of image re-use, which contextualises and relocates their functions in new interpretative formulas. The practice of found footage consists of the cinematographic, videographic and artistic practice of appropriation, re-elaboration and re- assembly of pre-existing images retrieved from heterogeneous media archives: from photography to stock footage and from home-movies to TV documentation and the web. One of the attractions of postmodern culture as a form of recycling, re-use and combination of different materials recovered from a past interpreted as a vast reservoir of imagery, found footage keeps its interest alive even in the epistemological trajectories of the so-called “new realism,” where a “society of recording” emerges (Ferraris 2011) in which everything must leave a trace and be archived. Moreover, deconstructionist thought has shown how inheritance should be understood not as a datum but always as a task, since archiving also responds to the need for regulation: preserving documents means imposing an order and establishing control through safeguarding and cataloguing devices. At the same time, audiovisual consumption practices have today become complex and composite forms of reception which rewrite the spectatorial experience and the uses and habits of accessibility, availability and relationship with films and audiovisual materials. The history of cinema is configured as a “visual deposit” (Bertozzi 2012) at the origin of the development of new formal writings and metaphorical processes. -

Teenie Weenie in a Too Big World: a Story for Fearful Children Free

FREE TEENIE WEENIE IN A TOO BIG WORLD: A STORY FOR FEARFUL CHILDREN PDF Margot Sunderland,Nicky Hancock,Nicky Armstrong | 32 pages | 03 Oct 2003 | Speechmark Publishing Ltd | 9780863884603 | English | Bicester, Oxon, United Kingdom ບິ ກິ ນີ - ວິ ກິ ພີ ເດຍ A novelty song is a type of song built upon some form of novel concept, such as a gimmicka piece of humor, or a sample of popular culture. Novelty songs partially overlap with comedy songswhich are more explicitly based on humor. Novelty songs achieved great popularity during the s and s. Novelty songs are often a parody or humor song, and may apply to a current event such as a holiday or a fad such as a dance or TV programme. Many use unusual Teenie Weenie in a Too Big World: A Story for Fearful Children, subjects, sounds, or instrumentation, and may not even be musical. It is based on their achievement Teenie Weenie in a Too Big World: A Story for Fearful Children a UK number-one single with " Doctorin' the Tardis ", a dance remix mashup of the Doctor Who theme music released under the name of 'The Timelords. Novelty songs were a major staple of Tin Pan Alley from its start in the late 19th century. They continued to proliferate in the early years of the 20th century, some rising to be among the biggest hits of the era. We Have No Bananas "; playful songs with a bit of double entendre, such as "Don't Put a Tax on All the Beautiful Girls"; and invocations of foreign lands with emphasis on general feel of exoticism rather than geographic or anthropological accuracy, such as " Oh By Jingo! These songs were perfect for the medium of Vaudevilleand performers such as Eddie Cantor and Sophie Tucker became well-known for such songs. -

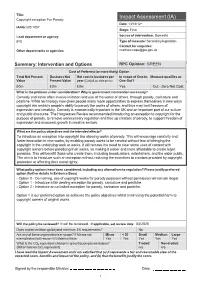

Copyright Exception for Parody Date: 13/12/12* IA No: BIS 1057 Stage: Final

Title: Impact Assessment (IA) Copyright exception For Parody Date: 13/12/12* IA No: BIS 1057 Stage: Final Lead department or agency: Source of intervention: Domestic IPO Type of measure: Secondary legislation Contact for enquiries: Other departments or agencies: [email protected] Summary: Intervention and Options RPC Opinion: GREEN Cost of Preferred (or more likely) Option Total Net Present Business Net Net cost to business per In scope of One-In, Measure qualifies as Value Present Value year (EANCB on 2009 prices) One-Out? £0m £0m £0m Yes Out - Zero Net Cost What is the problem under consideration? Why is government intervention necessary? Comedy and satire often involve imitation and use of the works of others, through parody, caricature and pastiche. While technology now gives people many more opportunities to express themselves in new ways copyright law restricts people's ability to parody the works of others, and thus may limit freedom of expression and creativity. Comedy is economically important in the UK and an important part of our culture and public discourse. The Hargreaves Review recommended introducing an exception to copyright for the purpose of parody, to remove unnecessary regulation and free up creators of parody, to support freedom of expression and economic growth in creative sectors. What are the policy objectives and the intended effects? To introduce an exception into copyright law allowing works of parody. This will encourage creativity and foster innovation in new works, by enabling parody works to be created without fear of infringing the copyright in the underlying work or works. It will remove the need to clear some uses of content with copyright owners before parodying their works, so making it easier and more affordable to create legal parodies. -

"WEIRD AL" YANKOVIC: POLKAS, PARODIES and the POWER of SATIRE by Chuck Miller Originally Published in Goldmine #514

"WEIRD AL" YANKOVIC: POLKAS, PARODIES AND THE POWER OF SATIRE By Chuck Miller Originally published in Goldmine #514 Al Yankovic strapped on his accordion, ready to perform. All he had to do was impress some talent directors, and he would be on The Gong Show, on stage with Chuck Barris and the Unknown Comic and Jaye P. Morgan and Gene Gene the Dancing Machine. "I was in college," said Yankovic, "and a friend and I drove down to LA for the day, and auditioned for The Gong Show. And we did a song called 'Mr. Frump in the Iron Lung.' And the audience seemed to enjoy it, but we never got called back. So we didn't make the cut for The Gong Show." But while the Unknown Co mic and Gene Gene the Dancing Machine are currently brain stumpers in 1970's trivia contests, the accordionist who failed the Gong Show taping became the biggest selling parodist and comedic recording artist of the past 30 years. His earliest parodies were recorded with an accordion in a men's room, but today, he and his band have replicated tracks so well one would think they borrowed the original master tape, wiped off the original vocalist, and superimposed Yankovic into the mix. And with MTV, MuchMusic, Dr. Demento and Radio Disney playing his songs right out of the box, Yankovic has reached a pinnacle of success and longevity most artists can only imagine. Alfred Yankovic was born in Lynwood, California on October 23, 1959. Seven years later, his parents bought him an accordion for his birthday. -

Types of Plagiarism & Unoriginal Work

TYPES OF PLAGIARISM & UNORIGINAL WORK The following information was taken from The Plagiarism Spectrum found at turnitin.com Click to Begin #1 CLONE Submitting someone else’s work, word-for-word, as your own. Previous Next CLONE From a survey of 900 secondary and higher education instructors, on a scale of 1-10, cloning ranks 9.5 and is both the most common and most severe type of plagiarism. Frequency 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Previous Next Cloning is intentional plagiarism and includes: using a friend’s paper from a previous class, purchasing a paper from a paper-mill, downloading a paper you found online, and other instances in which you turn in someone else’s work, unaltered, and claim it as your own. Previous Next #2 CTRL-C Containing significant portions of text from a single source with alterations. Previous Next CTRL-C From a survey of 900 secondary and higher education instructors, on a scale of 1-10, Ctrl-c ranks 8.9 and is the second most common type of plagiarism. Frequency 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Previous Next Ctrl-c is a common process in which although you have written some of the assignment and included your own thoughts, there are still significant portions that match up word-for-word to another person’s writing, without citation. This occurs often when you cull “research” from various sources, when in fact all you are doing is cutting- and-pasting various sentences from various sources to create paragraphs. -

Parody and Pastiche

Evaluating the Impact of Parody on the Exploitation of Copyright Works: An Empirical Study of Music Video Content on YouTube Parody and Pastiche. Study I. January 2013 Kris Erickson This is an independent report commissioned by the Intellectual Property Office (IPO) Intellectual Property Office is an operating name of the Patent Office © Crown copyright 2013 2013/22 Dr. Kris Erickson is Senior Lecturer in Media Regulation at the Centre ISBN: 978-1-908908-63-6 for Excellence in Media Practice, Bournemouth University Evaluating the impact of parody on the exploitation of copyright works: An empirical study of music (www.cemp.ac.uk). E-mail: [email protected] video content on YouTube Published by The Intellectual Property Office This is the first in a sequence of three reports on Parody & Pastiche, 8th January 2013 commissioned to evaluate policy options in the implementation of the Hargreaves Review of Intellectual Property & Growth (2011). This study 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 presents new empirical data about music video parodies on the online © Crown Copyright 2013 platform YouTube; Study II offers a comparative legal review of the law of parody in seven jurisdictions; Study III provides a summary of the You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the findings of Studies I & II, and analyses their relevance for copyright terms of the Open Government Licence. To view policy. this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov. uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or email: [email protected] The author is grateful for input from Dr. -

Andrea Lunsford Videos Plagiarism in the Remix Culture Lunsford Handbooks (Boston: Bedford/St. Martin's). 1/2 00:05

Andrea Lunsford Videos Plagiarism in the Remix Culture 00:05 ["Mark Herrera, Sustainability Major" onscreen] HERRERAR: You've got to give credit where it's due, and I think that you can't just steal people's ideas. 00:13 [ONSCREEN] Plagiarism in the Remix Culture 00:15 LUNSFORD: We do live in a remix culture. 00:17 ["Andrea A. Lunsford, Stanford University" onscreen] LUNSFORD: There's a war going on out there about who's going to have control over this cultural material. Do you want to be a victim of this war, or do you want to get in there and be one of the protagonists or antagonists in this? So I want you to think really carefully about how you are using the work of others. And if you want to pull a clip from a song and you want to mix it in with something you are writing, I want you to think about all of the ethical implications, and I want you to be ready to stand up and say "I'm taking responsibility for this, and I think I should be allowed to do this and here's why." If you can't do that, you'd better not. 01:02 ["Eder Diego, Communication Design Major" onscreen] DIEGO: In the future, I think I could see the paper as being a multimedia thing. When you turn in something, if the professor asks you to do something more than just the paper, you can have your paper and then have some kind of link to a video you might do on that topic. -

Fair Use Avoidance in Music Cases Edward Lee Chicago-Kent College of Law, [email protected]

Boston College Law Review Volume 59 | Issue 6 Article 2 7-11-2018 Fair Use Avoidance in Music Cases Edward Lee Chicago-Kent College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Edward Lee, Fair Use Avoidance in Music Cases, 59 B.C.L. Rev. 1873 (2018), https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol59/iss6/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FAIR USE AVOIDANCE IN MUSIC CASES EDWARD LEE INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1874 I. FAIR USE’S RELEVANCE TO MUSIC COMPOSITION ................................................................ 1878 A. Fair Use and the “Borrowing” of Copyrighted Content .................................................. 1879 1. Transformative Works ................................................................................................. 1879 2. Examples of Transformative Works ............................................................................ 1885 B. Borrowing in Music Composition ................................................................................... -

Fixing the Sample Music Industry: a Proposal for a Sample Compulsory License

FIXING THE SAMPLE MUSIC INDUSTRY: A PROPOSAL FOR A SAMPLE COMPULSORY LICENSE Maxwell Christiansen* INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 25 I. WHAT IS SAMPLING? .................................................................... 26 II. HISTORY OF AMERICAN MUSIC COPYRIGHT LAW ......................... 29 A. American Copyright Legislation ............................................ 29 B. Substantive Case Law ............................................................ 31 III. HOW CURRENT MUSIC COPYRIGHT LAW STIFLES CREATIVITY ..................................................................... 39 IV. PROPOSAL FOR A CONGRESSIONAL AMENDMENT TO THE COPYRIGHT ACT ........................................................................... 40 A. The Sample Compulsory License and the Emergence of a Sample License Organization ...................... 40 B. Justifications and a Balance of the Interests ......................... 42 C. Another Proposed Solution .................................................... 47 CONCLUSION .......................................................................................... 48 INTRODUCTION “Once music is recorded on tape, it’s just pieces of ferrous oxide on plastic, and can therefore be chopped about, switched around, put together in different orders, stretched, compressed, whatever,” explained Brian Eno, famous composer credited as the pioneer of ambient music,1 in a 1977 interview as he discussed the revolutionary benefits of magnetic tape -

Terror Nullius (2018) and the Politics of Sample Filmmaking

REVENGE REMIX: TERROR NULLIUS (2018) AND THE POLITICS OF SAMPLE FILMMAKING by Caitlin Lynch A Thesis SubmittEd for the DEgreE of MastEr of Arts to the Film StudiEs ProgrammE at ViCtoria University of WEllington – TE HErenga Waka April 2020 Lynch 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Thank you to my supervisors, Dr. Missy Molloy and Dr. Alfio LEotta for their generous guidancE, fEEdbaCk and encouragemEnt. Thank you also to Soda_JErk for their communiCation and support throughout my resEarch. Lynch 3 ABSTRACT TERROR NULLIUS (Soda_JErk, 2018) is an experimEntal samplE film that remixes Australian cinema, tElEvision and news mEdia into a “politiCal revenge fablE” (soda_jerk.co.au). WhilE TERROR NULLIUS is overtly politiCal in tone, understanding its speCifiC mEssages requires unpaCking its form, contEnt and cultural referencEs. This thesis investigatEs the multiplE layers of TERROR NULLIUS’ politiCs, thereby highlighting the politiCal stratEgiEs and capaCitiEs of samplE filmmaking. Employing a historiCal mEthodology, this resEarch contExtualisEs TERROR NULLIUS within a tradition of sampling and other subversive modes of filmmaking, including SoviEt cinema, Surrealism, avant-garde found-footage films, fan remix videos, and Australian archival art films. This comparative analysis highlights how Soda_JErk utilisE and advancE formal stratEgiEs of subversive appropriation, fair usE, dialECtiCal editing and digital compositing to intErrogatE the relationship betwEEn mEdia and culture. It also argues that TERROR NULLIUS Employs postmodern and postColonial approaChes -

Eduardo De Moura Almeida

UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS INSTITUTO DE ESTUDOS DA LINGUAGEM EDUARDO DE MOURA ALMEIDA ANIME MUSIC VIDEO (AMV), MULTI E NOVOS LETRAMENTOS: O REMIX NA CULTURA OTAKU CAMPINAS, 2018 EDUARDO DE MOURA ALMEIDA ANIME MUSIC VIDEO (AMV), MULTI E NOVOS LETRAMENTOS: O REMIX NA CULTURA OTAKU Tese de doutorado apresentada ao Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem da Universidade Estadual de Campinas para obtenção do título de Doutor em Linguística Aplicada na área de Linguagem e Educação Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Roxane Helena Rodrigues Rojo Este exemplar corresponde à versão final da Tese defendida pelo aluno Eduardo de Moura Almeida e orientada pela Profa. Dra. Roxane Helena Rodrigues Rojo CAMPINAS, 2018 Agência(s) de fomento e nº(s) de processo(s): FAPESP, 2015/22567-8; FAPESP, 2017/08441-7 Ficha catalográfica Universidade Estadual de Campinas Biblioteca do Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem Dionary Crispim de Araújo - CRB 8/7171 Almeida, Eduardo de Moura, 1981- AL64a AlmAnime Music Video (AMV), multi e novos letramentos : o remix na cultura otaku / Eduardo de Moura Almeida. – Campinas, SP : [s.n.], 2018. AlmOrientador: Roxane Helena Rodrigues Rojo. AlmTese (doutorado) – Universidade Estadual de Campinas, Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem. Alm1. Remixes. 2. Animação (Cinematografia). 3. Multiletramentos. 4. Cultura popular - Japão. I. Rojo, Roxane Helena Rodrigues. II. Universidade Estadual de Campinas. Instituto de Estudos da Linguagem. III. Título. Informações para Biblioteca Digital Título em outro idioma: Anime Music Video (AMV), multi and new