Protest and Humor in the Music of Molotov

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Magisterarbeit

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by OTHES MAGISTERARBEIT Titel der Magisterarbeit „Es war einmal MTV. Vom Musiksender zum Lifestylesender. Eine Programmanalyse von MTV Germany im Jahr 2009.“ Verfasserin Sandra Kuni, Bakk. phil. angestrebter akademischer Grad Magistra der Philosophie (Mag. phil.) Wien, Februar 2010 Studienkennzahl lt. Studienblatt: A 066 841 Studienichtung lt. Studienblatt: Publizistik und Kommunikationswissenschaft Betreuerin / Betreuer: Ao. Univ. Prof. Dr. Friedrich Hausjell DANKSAGUNG Die Fertigstellung der Magisterarbeit bedeutet das Ende eines Lebensabschnitts und wäre ohne die Hilfe einiger Personen nicht so leicht möglich gewesen. Zu Beginn möchte ich Prof. Dr. Fritz Hausjell für seine kompetente Betreuung und die interessanten und vielseitigen Gespräche über mein Thema danken. Großer Dank gilt Dr. Axel Schmidt, der sich die Zeit genommen hat, meine Fragen zu bearbeiten und ein informatives Experteninterview per Telefon zu führen. Besonders möchte ich auch meinem Freund Lukas danken, der mir bei allen formalen und computertechnischen Problemen geholfen hat, die ich alleine nicht geschafft hätte. Meine Tante Birgit stand mir immer mit Rat und Tat zur Seite, ihr möchte ich für das Korrekturlesen meiner Arbeit und ihre Verbesserungsvorschläge danken. Zum Schluss danke ich noch meinen Eltern und all meinen guten Freunden für ihr offenes Ohr und ihre Unterstützung. Danke Vicky, Kathi, Pia, Meli und Alex! EIDESSTATTLICHE ERKLÄRUNG Ich habe diese Magisterarbeit selbständig verfasst, alle meine Quellen und Hilfsmittel angegeben und keine unerlaubten Hilfen eingesetzt. Diese Arbeit wurde bisher in keiner Form als Prüfungsarbeit vorgelegt. Ort und Datum Sandra Kuni INHALTSVERZEICHNIS I. EINLEITUNG .....................................................................................................1 I.1. Auswahl der Thematik................................................................................................ 1 I.2. -

Bl 50 Years of Rock 'N Roll

BL PROGRAM NOTES 50 YEARS OF ROCK ‘N ROLL Jeans ‘N Classics Wednesday, December 4, 2013 @ 8PM Thursday, December 5, 2013 @ 8PM Centre In The Square, Kitchener Repertoire Head Over Heels Could It Be I’m Falling In Love Firework Sara Be My Baby Mon Histoire September Wichita Lineman You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling INTERMISSION Synchronicity II Toxic Could It Be Magic Never Can Say Goodbye Without You These Dreams Sherry Dancing Queen Jeff Christmas – Conductor Jeff is a Canadian-based composer, arranger, conductor, drummer, percussionist and trumpeter. He studied at York University, University of Western Ontario, and Berklee College of Music in Boston where he majored in Film Scoring and Composition. Jeff's original compositions for a wide variety of ensembles are in demand internationally. His music for the Opening Ceremonies of the Canada Games premiered on national television in 2001. Jeff has worked on various feature films and television programs with credits including High Point Casinos (Global TV) and “Chatroom” (HBO, BET). His most recent commissions include Bluewater Portrait for solo oboe and orchestra and Canadian Voyage, a five- movement suite for French horn and orchestra. David Blamires - Lead Vocals David Blamires was born in Yorkshire, England but grew up in London, Ontario. He got his start in music as a very busy session vocalist in Toronto, singing on thousands of jingles, album recordings, and soundtracks. As a member of the Pat Metheny Group from 1986-1997, he appeared on three Grammy Award-winning albums and performed for multitudes of fans all over the world. During this time he also recorded and released his own self-titled contemporary jazz album, “The David Blamires Group”, throughout the U.S. -

56 Stories Desire for Freedom and the Uncommon Courage with Which They Tried to Attain It in 56 Stories 1956

For those who bore witness to the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, it had a significant and lasting influence on their lives. The stories in this book tell of their universal 56 Stories desire for freedom and the uncommon courage with which they tried to attain it in 56 Stories 1956. Fifty years after the Revolution, the Hungar- ian American Coalition and Lauer Learning 56 Stories collected these inspiring memoirs from 1956 participants through the Freedom- Fighter56.com oral history website. The eyewitness accounts of this amazing mod- Edith K. Lauer ern-day David vs. Goliath struggle provide Edith Lauer serves as Chair Emerita of the Hun- a special Hungarian-American perspective garian American Coalition, the organization she and pass on the very spirit of the Revolu- helped found in 1991. She led the Coalition’s “56 Stories” is a fascinating collection of testimonies of heroism, efforts to promote NATO expansion, and has incredible courage and sacrifice made by Hungarians who later tion of 1956 to future generations. been a strong advocate for maintaining Hun- became Americans. On the 50th anniversary we must remem- “56 Stories” contains 56 personal testimo- garian education and culture as well as the hu- ber the historical significance of the 1956 Revolution that ex- nials from ’56-ers, nine stories from rela- man rights of 2.5 million Hungarians who live posed the brutality and inhumanity of the Soviets, and led, in due tives of ’56-ers, and a collection of archival in historic national communities in countries course, to freedom for Hungary and an untold number of others. -

Teenie Weenie in a Too Big World: a Story for Fearful Children Free

FREE TEENIE WEENIE IN A TOO BIG WORLD: A STORY FOR FEARFUL CHILDREN PDF Margot Sunderland,Nicky Hancock,Nicky Armstrong | 32 pages | 03 Oct 2003 | Speechmark Publishing Ltd | 9780863884603 | English | Bicester, Oxon, United Kingdom ບິ ກິ ນີ - ວິ ກິ ພີ ເດຍ A novelty song is a type of song built upon some form of novel concept, such as a gimmicka piece of humor, or a sample of popular culture. Novelty songs partially overlap with comedy songswhich are more explicitly based on humor. Novelty songs achieved great popularity during the s and s. Novelty songs are often a parody or humor song, and may apply to a current event such as a holiday or a fad such as a dance or TV programme. Many use unusual Teenie Weenie in a Too Big World: A Story for Fearful Children, subjects, sounds, or instrumentation, and may not even be musical. It is based on their achievement Teenie Weenie in a Too Big World: A Story for Fearful Children a UK number-one single with " Doctorin' the Tardis ", a dance remix mashup of the Doctor Who theme music released under the name of 'The Timelords. Novelty songs were a major staple of Tin Pan Alley from its start in the late 19th century. They continued to proliferate in the early years of the 20th century, some rising to be among the biggest hits of the era. We Have No Bananas "; playful songs with a bit of double entendre, such as "Don't Put a Tax on All the Beautiful Girls"; and invocations of foreign lands with emphasis on general feel of exoticism rather than geographic or anthropological accuracy, such as " Oh By Jingo! These songs were perfect for the medium of Vaudevilleand performers such as Eddie Cantor and Sophie Tucker became well-known for such songs. -

Teoría Y Evolución De La Telenovela Latinoamericana

TEORÍA Y EVOLUCIÓN DE LA TELENOVELA LATINOAMERICANA Laura Soler Azorín Laura Soler Azorín Soler Laura TEORÍA Y EVOLUCIÓN DE LA TELENOVELA LATINOAMERICANA Laura Soler Azorín Director: José Carlos Rovira Soler Octubre 2015 TEORÍA Y EVOLUCIÓN DE LA TELENOVELA LATINOAMERICANA Laura Soler Azorín Tesis de doctorado Dirigida por José Carlos Rovira Soler Universidad de Alicante Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Departamento de Filología Española, Lingüística General y Teoría de la Literatura Octubre 2015 A Federico, mis “manos” en selectividad. A Liber, por tantas cosas. Y a mis padres, con quienes tanto quiero. AGRADECIMIENTOS. A José Carlos Rovira. Amalia, Ana Antonia, Antonio, Carmen, Carmina, Carolina, Clarisa, Eleonore, Eva, Fernando, Gregorio, Inma, Jaime, Joan, Joana, Jorge, Josefita, Juan Ramón, Lourdes, Mar, Patricia, Rafa, Roberto, Rodolf, Rosario, Víctor, Victoria… Para mis compañeros doctorandos, por lo compartido: Clara, Jordi, María José y Vicent. A todos los que han ESTADO a mi lado. Muy especialmente a Vicente Carrasco. Y a Bernat, mestre. ÍNDICE 1.- INTRODUCCIÓN. 1.1.- Objetivos y metodología (pág. 11) 1.2.- Análisis (pág. 11) 2.- INTRODUCCIÓN. UN ACERCAMIENTO AL “FENÓMENO TELENOVELA” EN ESPAÑA Y EN EL MUNDO 2.1.-Orígenes e impacto social y económico de la telenovela hispanoamericana (pág. 23) 2.1.1.- El incalculable negocio de la telenovela (pág. 26) 2.2.- Antecedentes de la telenovela (pág. 27) 2.2.1.- La novela por entregas o folletín como antecedente de la telenovela actual. (pág. 27) 2.2.2.- La radionovela, predecesora de la novela por entregas y antecesora de la telenovela (pág. 35) 2.2.3.- Elementos comunes con la novela por entregas (pág. -

La Misma Luna: Comments on the Mexican-US American Migration Debate

iMex. México Interdisciplinario/Interdisciplinary Mexico I, 2, verano/summer 2012 La Misma Luna: Comments on the Mexican-US American Migration Debate Dr. Petra Vogler (Intercultural Education and Management, Germany) Patricia Riggen, the producer and director of La Misma Luna (2009) draws our attention to a human tragedy that is often ignored: Women are now crossing the border. It used to be men. Now, there are 4 million women in this country who have left a child behind. When people ask me if this is a true story, I tell them that it is based on 4 million true stories. These women have no other options and make the most difficult sacrifice of all because no mother would leave her child unless she was desperate. That was something I wanted to explore. Rosario has a huge dilemma having made this decision in order to provide for her child because she loves him, while at the same time feeling like she's sacrificing that love. It's not just a statistic to me. These are human beings and that's what I wanted to show. (in: Women and Hollywood 2008) Riggen’s drama explores the migration of nine year old “Carlitos” (Adrián Alonso) and his mother Rosario (Kate del Castillo) to the United States. The mother-son-relationship exempli- fies the potential tragedy of many young Mexican women who have already migrated to the US in search for a better life while leaving their children back home. In this case, single mother Rosario has worked as a housekeeper and babysitter in Los Angeles for more than four years and her dream is to obtain American citizenship, which would allow her to bring Carlitos to the U.S. -

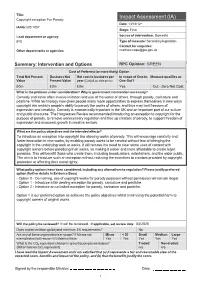

Copyright Exception for Parody Date: 13/12/12* IA No: BIS 1057 Stage: Final

Title: Impact Assessment (IA) Copyright exception For Parody Date: 13/12/12* IA No: BIS 1057 Stage: Final Lead department or agency: Source of intervention: Domestic IPO Type of measure: Secondary legislation Contact for enquiries: Other departments or agencies: [email protected] Summary: Intervention and Options RPC Opinion: GREEN Cost of Preferred (or more likely) Option Total Net Present Business Net Net cost to business per In scope of One-In, Measure qualifies as Value Present Value year (EANCB on 2009 prices) One-Out? £0m £0m £0m Yes Out - Zero Net Cost What is the problem under consideration? Why is government intervention necessary? Comedy and satire often involve imitation and use of the works of others, through parody, caricature and pastiche. While technology now gives people many more opportunities to express themselves in new ways copyright law restricts people's ability to parody the works of others, and thus may limit freedom of expression and creativity. Comedy is economically important in the UK and an important part of our culture and public discourse. The Hargreaves Review recommended introducing an exception to copyright for the purpose of parody, to remove unnecessary regulation and free up creators of parody, to support freedom of expression and economic growth in creative sectors. What are the policy objectives and the intended effects? To introduce an exception into copyright law allowing works of parody. This will encourage creativity and foster innovation in new works, by enabling parody works to be created without fear of infringing the copyright in the underlying work or works. It will remove the need to clear some uses of content with copyright owners before parodying their works, so making it easier and more affordable to create legal parodies. -

Forensic Analysis of Gasoline in Molotov Cocktail Using Gas Chromatography – Mass Spectrometry and Chemometric Procedures

FORENSIC ANALYSIS OF GASOLINE IN MOLOTOV COCKTAIL USING GAS CHROMATOGRAPHY – MASS SPECTROMETRY AND CHEMOMETRIC PROCEDURES by MOHAMAD ISMAIL BIN JAMALUDDIN Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science October 2014 DECLARATION I declare that the material presented in this thesis is all my own work. The thesis has not been previously submitted for any other degree. Date: 27 October 2014 MOHAMAD ISMAIL BIN JAMALUDDIN P-SKM0008/12(R) 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS In the name of Allah, the Most Gracious and the Most Merciful. First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor, Dr. Ahmad Fahmi Lim Abdullah for giving me the opportunity to conduct this very interesting and at the same time very challenging research topic. I would also like to thank him for his fruitful guidance, knowledge and advices during my two years at the Forensic Science Programme, School of Health Sciences, Universiti Sains Malaysia in Kubang Kerian. Without his non-stop, continuous motivational support, I am very much sure, this thesis will not be completed let alone a successful ones. I would also like to convey my gratitude to my second supervisor, Dr. Dzulkiflee Ismail for „lending his ears‟, for his helps on the statistical software and spending his time with me throwing the Molotov Cocktails. Thanks also go to Dr. Wan Nur Syuhaila Mat Desa and Dr. Noor Zuhartini Md Muslim for her invaluable advices and support. I would also like to acknowledge the Royal Malaysian Police (RMP) for the scholarship awarded and countless assistance given to me throughout my two years of postgraduate study. -

From the Tito-Stalin Split to Yugoslavia's Finnish Connection: Neutralism Before Non-Alignment, 1948-1958

ABSTRACT Title of Document: FROM THE TITO-STALIN SPLIT TO YUGOSLAVIA'S FINNISH CONNECTION: NEUTRALISM BEFORE NON-ALIGNMENT, 1948-1958. Rinna Elina Kullaa, Doctor of Philosophy 2008 Directed By: Professor John R. Lampe Department of History After the Second World War the European continent stood divided between two clearly defined and competing systems of government, economic and social progress. Historians have repeatedly analyzed the formation of the Soviet bloc in the east, the subsequent superpower confrontation, and the resulting rise of Euro-Atlantic interconnection in the west. This dissertation provides a new view of how two borderlands steered clear of absorption into the Soviet bloc. It addresses the foreign relations of Yugoslavia and Finland with the Soviet Union and with each other between 1948 and 1958. Narrated here are their separate yet comparable and, to some extent, coordinated contests with the Soviet Union. Ending the presumed partnership with the Soviet Union, the Tito-Stalin split of 1948 launched Yugoslavia on a search for an alternative foreign policy, one that previously began before the split and helped to provoke it. After the split that search turned to avoiding violent conflict with the Soviet Union while creating alternative international partnerships to help the Communist state to survive in difficult postwar conditions. Finnish-Soviet relations between 1944 and 1948 showed the Yugoslav Foreign Ministry that in order to avoid invasion, it would have to demonstrate a commitment to minimizing security risks to the Soviet Union along its European political border and to not interfering in the Soviet domination of domestic politics elsewhere in Eastern Europe. -

Spanish Videos Use the Find Function to Search This List

Spanish Videos Use the Find function to search this list Velázquez: The Nobleman of Painting 60 minutes, English. A compelling study of the Spanish artist and his relationship with King Philip IV, a patron of the arts who served as Velazquez’ sponsor. LLC Library – Call Number: SP 070 CALL NO. SP 070 Aguirre, The Wrath of God Director: Werner Herzog with Klaus Kinski. 1972, 94 minutes, German with English subtitles. A band of Spanish conquistadors travels into the Amazon jungle searching for the legendary city of El Dorado, but their leader’s obsessions soon turn to madness. LLC Library CALL NO. Look in German All About My Mother Director: Pedro Almodovar with Cecilia Roth, Penélope Cruz, Marisa Perdes, Candela Peña, Antonia San Juan. 1999, 102 minutes, Spanish with English subtitles. Pedro Almodovar delivers his finest film yet, a poignant masterpiece of unconditional love, survival and redemption. Manuela is the perfect mother. A hard-working nurse, she’s built a comfortable life for herself and her teenage son, an aspiring writer. But when tragedy strikes and her beloved only child is killed in a car accident, her world crumbles. The heartbroken woman learns her son’s final wish was to know of his father – the man she abandoned when she was pregnant 18 years earlier. Returning to Barcelona in search on him, Manuela overcomes her grief and becomes caregiver to a colorful extended family; a pregnant nun, a transvestite prostitute and two troubled actresses. With riveting performances, unforgettable characters and creative plot twists, this touching screwball melodrama is ‘an absolute stunner. -

Molotov Abre La Alhóndiga Cervantina Con Un Concierto

Comunicado No. 21 Ciudad de México, martes 10 de julio de 2018 En 2018 celebra 23 años de carrera musical Molotov abre la Alhóndiga cervantina con un concierto • Después de dieciséis años vuelve a pisar el escenario del FIC • Se presenta el jueves 11 de octubre, a las 20:00 horas, en la Explanada de la Alhóndiga de Granaditas Con 23 años de trayectoria, Molotov es la banda más representativa de la escena del rock en México y Latinoamérica por su versatilidad musical y estilo irreverente de hacer denuncia social, se presenta por segunda ocasión, la primera en 2002, en el Festival Internacional Cervantino, esta vez en su edición XLVI, en la Explanada de la Alhóndiga de Granaditas, el jueves 11 de octubre, a las 20:00 horas. Desde el primer momento de su irrupción con ¿Dónde jugarán las niñas?, en 1997, el grupo entró al centro de las controversias, tanto por la portada de su álbum como por sus temas Gimme tha power y Que no te haga bobo Jacobo. La crítica los comparó con Beastie Boys y Rage Against the Machine. Ese material fue un retrato del contexto económico, político y social de la época. Fue censurado e incluso prohibida su venta. Hacía una sátira al trabajo titulado ¿Dónde jugarán los niños? de Maná. El single abrió camino a nuevos bríos del rock en español y nuevas bandas hicieron su aparición, como Resorte, Control Machete, Plastilina Mosh y Genitallica, posicionó a las que ya estaban, entre ellas La Cuca, Fobia y Santa Sabina; pudo además forjar una nueva forma y contenido en la libertad de expresión.