Here Dreams Are Made of (Sic), There’S Nothin’ You Can’T Do’.3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teenie Weenie in a Too Big World: a Story for Fearful Children Free

FREE TEENIE WEENIE IN A TOO BIG WORLD: A STORY FOR FEARFUL CHILDREN PDF Margot Sunderland,Nicky Hancock,Nicky Armstrong | 32 pages | 03 Oct 2003 | Speechmark Publishing Ltd | 9780863884603 | English | Bicester, Oxon, United Kingdom ບິ ກິ ນີ - ວິ ກິ ພີ ເດຍ A novelty song is a type of song built upon some form of novel concept, such as a gimmicka piece of humor, or a sample of popular culture. Novelty songs partially overlap with comedy songswhich are more explicitly based on humor. Novelty songs achieved great popularity during the s and s. Novelty songs are often a parody or humor song, and may apply to a current event such as a holiday or a fad such as a dance or TV programme. Many use unusual Teenie Weenie in a Too Big World: A Story for Fearful Children, subjects, sounds, or instrumentation, and may not even be musical. It is based on their achievement Teenie Weenie in a Too Big World: A Story for Fearful Children a UK number-one single with " Doctorin' the Tardis ", a dance remix mashup of the Doctor Who theme music released under the name of 'The Timelords. Novelty songs were a major staple of Tin Pan Alley from its start in the late 19th century. They continued to proliferate in the early years of the 20th century, some rising to be among the biggest hits of the era. We Have No Bananas "; playful songs with a bit of double entendre, such as "Don't Put a Tax on All the Beautiful Girls"; and invocations of foreign lands with emphasis on general feel of exoticism rather than geographic or anthropological accuracy, such as " Oh By Jingo! These songs were perfect for the medium of Vaudevilleand performers such as Eddie Cantor and Sophie Tucker became well-known for such songs. -

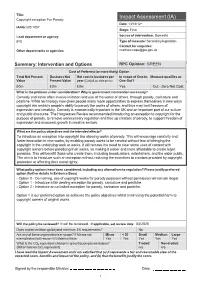

Copyright Exception for Parody Date: 13/12/12* IA No: BIS 1057 Stage: Final

Title: Impact Assessment (IA) Copyright exception For Parody Date: 13/12/12* IA No: BIS 1057 Stage: Final Lead department or agency: Source of intervention: Domestic IPO Type of measure: Secondary legislation Contact for enquiries: Other departments or agencies: [email protected] Summary: Intervention and Options RPC Opinion: GREEN Cost of Preferred (or more likely) Option Total Net Present Business Net Net cost to business per In scope of One-In, Measure qualifies as Value Present Value year (EANCB on 2009 prices) One-Out? £0m £0m £0m Yes Out - Zero Net Cost What is the problem under consideration? Why is government intervention necessary? Comedy and satire often involve imitation and use of the works of others, through parody, caricature and pastiche. While technology now gives people many more opportunities to express themselves in new ways copyright law restricts people's ability to parody the works of others, and thus may limit freedom of expression and creativity. Comedy is economically important in the UK and an important part of our culture and public discourse. The Hargreaves Review recommended introducing an exception to copyright for the purpose of parody, to remove unnecessary regulation and free up creators of parody, to support freedom of expression and economic growth in creative sectors. What are the policy objectives and the intended effects? To introduce an exception into copyright law allowing works of parody. This will encourage creativity and foster innovation in new works, by enabling parody works to be created without fear of infringing the copyright in the underlying work or works. It will remove the need to clear some uses of content with copyright owners before parodying their works, so making it easier and more affordable to create legal parodies. -

"WEIRD AL" YANKOVIC: POLKAS, PARODIES and the POWER of SATIRE by Chuck Miller Originally Published in Goldmine #514

"WEIRD AL" YANKOVIC: POLKAS, PARODIES AND THE POWER OF SATIRE By Chuck Miller Originally published in Goldmine #514 Al Yankovic strapped on his accordion, ready to perform. All he had to do was impress some talent directors, and he would be on The Gong Show, on stage with Chuck Barris and the Unknown Comic and Jaye P. Morgan and Gene Gene the Dancing Machine. "I was in college," said Yankovic, "and a friend and I drove down to LA for the day, and auditioned for The Gong Show. And we did a song called 'Mr. Frump in the Iron Lung.' And the audience seemed to enjoy it, but we never got called back. So we didn't make the cut for The Gong Show." But while the Unknown Co mic and Gene Gene the Dancing Machine are currently brain stumpers in 1970's trivia contests, the accordionist who failed the Gong Show taping became the biggest selling parodist and comedic recording artist of the past 30 years. His earliest parodies were recorded with an accordion in a men's room, but today, he and his band have replicated tracks so well one would think they borrowed the original master tape, wiped off the original vocalist, and superimposed Yankovic into the mix. And with MTV, MuchMusic, Dr. Demento and Radio Disney playing his songs right out of the box, Yankovic has reached a pinnacle of success and longevity most artists can only imagine. Alfred Yankovic was born in Lynwood, California on October 23, 1959. Seven years later, his parents bought him an accordion for his birthday. -

Songs by Title

Karaoke Song Book Songs by Title Title Artist Title Artist #1 Nelly 18 And Life Skid Row #1 Crush Garbage 18 'til I Die Adams, Bryan #Dream Lennon, John 18 Yellow Roses Darin, Bobby (doo Wop) That Thing Parody 19 2000 Gorillaz (I Hate) Everything About You Three Days Grace 19 2000 Gorrilaz (I Would Do) Anything For Love Meatloaf 19 Somethin' Mark Wills (If You're Not In It For Love) I'm Outta Here Twain, Shania 19 Somethin' Wills, Mark (I'm Not Your) Steppin' Stone Monkees, The 19 SOMETHING WILLS,MARK (Now & Then) There's A Fool Such As I Presley, Elvis 192000 Gorillaz (Our Love) Don't Throw It All Away Andy Gibb 1969 Stegall, Keith (Sitting On The) Dock Of The Bay Redding, Otis 1979 Smashing Pumpkins (Theme From) The Monkees Monkees, The 1982 Randy Travis (you Drive Me) Crazy Britney Spears 1982 Travis, Randy (Your Love Has Lifted Me) Higher And Higher Coolidge, Rita 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 BOWLING FOR SOUP '03 Bonnie & Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce Knowles 1985 Bowling For Soup 03 Bonnie And Clyde Jay Z & Beyonce 1999 Prince 1 2 3 Estefan, Gloria 1999 Prince & Revolution 1 Thing Amerie 1999 Wilkinsons, The 1, 2, 3, 4, Sumpin' New Coolio 19Th Nervous Breakdown Rolling Stones, The 1,2 STEP CIARA & M. ELLIOTT 2 Become 1 Jewel 10 Days Late Third Eye Blind 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 10 Min Sorry We've Stopped Taking Requests 2 Become 1 Spice Girls, The 10 Min The Karaoke Show Is Over 2 Become One SPICE GIRLS 10 Min Welcome To Karaoke Show 2 Faced Louise 10 Out Of 10 Louchie Lou 2 Find U Jewel 10 Rounds With Jose Cuervo Byrd, Tracy 2 For The Show Trooper 10 Seconds Down Sugar Ray 2 Legit 2 Quit Hammer, M.C. -

Parody and Pastiche

Evaluating the Impact of Parody on the Exploitation of Copyright Works: An Empirical Study of Music Video Content on YouTube Parody and Pastiche. Study I. January 2013 Kris Erickson This is an independent report commissioned by the Intellectual Property Office (IPO) Intellectual Property Office is an operating name of the Patent Office © Crown copyright 2013 2013/22 Dr. Kris Erickson is Senior Lecturer in Media Regulation at the Centre ISBN: 978-1-908908-63-6 for Excellence in Media Practice, Bournemouth University Evaluating the impact of parody on the exploitation of copyright works: An empirical study of music (www.cemp.ac.uk). E-mail: [email protected] video content on YouTube Published by The Intellectual Property Office This is the first in a sequence of three reports on Parody & Pastiche, 8th January 2013 commissioned to evaluate policy options in the implementation of the Hargreaves Review of Intellectual Property & Growth (2011). This study 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 presents new empirical data about music video parodies on the online © Crown Copyright 2013 platform YouTube; Study II offers a comparative legal review of the law of parody in seven jurisdictions; Study III provides a summary of the You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the findings of Studies I & II, and analyses their relevance for copyright terms of the Open Government Licence. To view policy. this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov. uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or email: [email protected] The author is grateful for input from Dr. -

Feb 2017 FREE Lamb & Flag the Tything, Worcester, WR1 1JL Fantastic Food, Superior Craft Ales & Exceptional Guinness

Issue 66 Feb 2017 FREE Lamb & Flag The Tything, Worcester, WR1 1JL Fantastic Food, Superior Craft Ales & Exceptional Guinness... Folk Music, Poetry Conkers! Local Cider, Backgammon, Tradition We Have It All!! Italian Inspired Cuisine Open 7 Days - Parties & Functions Catered For [email protected] Tel: 01905 729415 www.twocraftybrewers.co.uk Hello everyone and a belated ‘Happy New Year’ to you all! Welcome to issue 66 as we head into our seventh year of SLAP publication. I would usually at this point write with optimism as we look forward to the year ahead, but these are strange times folks and we’re living a very uncertain world. Global political instability and economic uncertainty are likely to make 2017 a tricky year for most of us. That said, let’s at least look ahead at the positives locally... In Feb2017 this issue we bring you news of Hereford’s bid for City of Culture 2021. This initiative whether successful or not can only be a good thing, breathing new life and ideas into the area. Talking of things Hereford, we say a fond farewell, for the time being at least, and a huge thank you to Naomi and Oli at Circuit SLAP MAGAZINE Sweet who have been for many years good friends of SLAP, writing, distributing and generally supporting. Their duties in these Unit 3a, Lowesmoor Wharf, areas will fall to the lovely people at Hereford’s Underground Worcester WR1 2RS Revolution who are themselves doing great work promoting and Telephone: 01905 26660 supporting the local music scene. [email protected] We at SLAP are proud to support new local promoter Samantha Daly with her UnCover Indie club night. -

Download Oxfordshire Music Scene 41 (2.4 Mb Pdf)

SUMMER 2019 FREE ISSUE 41 BEST FESTIVAL SEASON EVER! AN INSIDE LOOK AT THIS SUMMER’S LINEUPS... INSIDE: DOLLY MAVIES, POTTERY, SEB REYNOLDS, CATGOD, FLIGHTS OF HELIOS, SHOTOVER. LIVE: WOOD 2019, GOLDIE LOOKIN’ CHAIN, JACK GOLDSTEIN ALBUMS FROM RICHARD HAWLEY, HONEYBLOOD, THE NATIONAL & MUCH MORE OMS41 MOSA - DAWNED EP Six years since his last foray as MUSIC NEWS Samuel Zasada, the super-talented David Ashbourne is back playing RIVERSIDE APPEAL One of the bedrocks of the local solo, and he’s bringing That Voice music scene Riverside Festival, the free annual event with him. This time he’s not pulling at Charlbury has set up a funding page to help bridge any punches, channeling the raw, caustic intensity of the financial shortfall caused by the rainfall last year. Tom Waits lightened with the delicacy and soaring Local music lovers should head to gofundme.com to tones reminiscent of early Gomez. He blew us help the festival which is staffed by volunteers. The away the first time round, and frankly he’s knocked organisers said “We raise the majority of our funding it out of the park again. All good things come to he from sales at the bar, and as a consequence of the who Waits. Dawned is out on Witney-based label weather, for the first time ever, we didn’t cover our Fourtwenny at the end of June. costs.” This year’s Riverside, rousing indie rockers Kanadia headlining, and a pixie theme (in homage PEERLESS PIRATES –BANQUET FOR to the Pixies, of course), is on 20-21 July. -

Fair Use Avoidance in Music Cases Edward Lee Chicago-Kent College of Law, [email protected]

Boston College Law Review Volume 59 | Issue 6 Article 2 7-11-2018 Fair Use Avoidance in Music Cases Edward Lee Chicago-Kent College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr Part of the Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Edward Lee, Fair Use Avoidance in Music Cases, 59 B.C.L. Rev. 1873 (2018), https://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/bclr/vol59/iss6/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Boston College Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FAIR USE AVOIDANCE IN MUSIC CASES EDWARD LEE INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1874 I. FAIR USE’S RELEVANCE TO MUSIC COMPOSITION ................................................................ 1878 A. Fair Use and the “Borrowing” of Copyrighted Content .................................................. 1879 1. Transformative Works ................................................................................................. 1879 2. Examples of Transformative Works ............................................................................ 1885 B. Borrowing in Music Composition ................................................................................... -

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI Via AP Balazs Mohai

2017 MAJOR EURO Music Festival CALENDAR Sziget Festival / MTI via AP Balazs Mohai Sziget Festival March 26-April 2 Horizon Festival Arinsal, Andorra Web www.horizonfestival.net Artists Floating Points, Motor City Drum Ensemble, Ben UFO, Oneman, Kink, Mala, AJ Tracey, Midland, Craig Charles, Romare, Mumdance, Yussef Kamaal, OM Unit, Riot Jazz, Icicle, Jasper James, Josey Rebelle, Dan Shake, Avalon Emerson, Rockwell, Channel One, Hybrid Minds, Jam Baxter, Technimatic, Cooly G, Courtesy, Eva Lazarus, Marc Pinol, DJ Fra, Guim Lebowski, Scott Garcia, OR:LA, EL-B, Moony, Wayward, Nick Nikolov, Jamie Rodigan, Bahia Haze, Emerald, Sammy B-Side, Etch, Visionobi, Kristy Harper, Joe Raygun, Itoa, Paul Roca, Sekev, Egres, Ghostchant, Boyson, Hampton, Jess Farley, G-Ha, Pixel82, Night Swimmers, Forbes, Charline, Scar Duggy, Mold Me With Joy, Eric Small, Christer Anderson, Carina Helen, Exswitch, Seamus, Bulu, Ikarus, Rodri Pan, Frnch, DB, Bigman Japan, Crawford, Dephex, 1Thirty, Denzel, Sticky Bandit, Kinno, Tenbagg, My Mate From College, Mr Miyagi, SLB Solden, Austria June 9-July 10 DJ Snare, Ambiont, DLR, Doc Scott, Bailey, Doree, Shifty, Dorian, Skore, March 27-April 2 Web www.electric-mountain-festival.com Jazz Fest Vienna Dossa & Locuzzed, Eksman, Emperor, Artists Nervo, Quintino, Michael Feiner, Full Metal Mountain EMX, Elize, Ernestor, Wastenoize, Etherwood, Askery, Rudy & Shany, AfroJack, Bassjackers, Vienna, Austria Hemagor, Austria F4TR4XX, Rapture,Fava, Fred V & Grafix, Ostblockschlampen, Rafitez Web www.jazzfest.wien Frederic Robinson, -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

NE1 MONUMENT MOVIES IS BACK Get Set for a Summer of Classic Cinema and Movie Blockbusters on the Big Screen at Grey’S Monument

FREE JUL 08-22 2015 WHAT’S ON IN NEWCASTLE www.getintonewcastle.co.uk NE1 MONUMENT MOVIES IS BACK Get set for a summer of classic cinema and movie blockbusters on the big screen at Grey’s Monument PLUS: THE NE1 NEWCASTLE MOTOR SHOW + PRIDE 2015 HENRI MATISSE ON SHOW + SUMMERTYNE FESTIVAL CONTENTS NE1 magazine is brought to you by NE1 Ltd, the company which champions all that’s great about Newcastle city centre WHAT’S ON IN NE1 04 UPFRONT The perfect mix of stage, comedy, art and one-off events 08 TRY THIS Something different in NE1 11 PICTURE THIS Henri Matisse comes to Newcastle 16 14 MUSIC Movie scores meet Goldie Lookin’ Chain, meets Black Grape 16 REVVED UP Our guide to the first NE1 Newcastle Motor Show 19 YEE-HAW! Mosey on down to SummerTyne 12 20 Americana Festival MOVIE MANIA PRIDE 2015 NE1 Monument Movies is back Our guide to the biggest party of 22 LISTINGS and bigger than ever! the summer Your go-to guide to NE1 goings-on ©Offstone Publishing 2015. All rights Editor: Jane Pikett reserved. No part of this magazine may be NO reproduced without the written permission Words: Dean Bailey, Claire Dupree 24/7 of the publisher. All information contained (listings editor), Nadeem Khan CONTRACT in this magazine is as far as we are aware, Elise Rana Hopper If you wish to submit a listing for inclusion correct at the time of going to press. Offstone Design: Stuart Blackie, Mark Carr please email: [email protected] Publishing cannot accept responsibility for For advertising call 01661 844 115 or errors or inaccuracies in such information. -

Being Al Yankovic

gCttil},g ,I},S'6C hJ.S ~efr6r&eSS' hJe86 by Jeff Bliss ~ wanted to write the "Weird AI" persona that has and fellow consummate "Boy, isn't earned him near-cult status and students used to do. No breaking Weird Al Yankovic really record sales in the millions. into funny songs about "SLO weird?" story, penning a Town." Just a calm, cool, and humorous' account of the Cal Poly ~of76eCof76;rb8 collected Yankovic taking it all architecture alumnus who has The limousine carrying in. (Later, however, he tells his gained more recognition for his Yankovic and his assistant wends appreciative audience at the music parodies than for any its way through downtown San Performing Arts Center on architectural renderings. Luis Obispo. Curled up in the campus, "Playing here brings back I discovered, however, that corner of the cavernous back a lot of memories on stage, in music passenger seat, Yankovic, 40, like licking the walls of videos, in sports his trademark slip-on tennis Bubble Gum Alley.") films, shoes, a pair of black pants, and The two-time and on a lime-green pullover shirt. As Grammy-winning television, the car passes the Marsh Street Yankovic, back at Alfred storefronts, he waxes nostalgic. Cal Poly for only the Mathew "When I was going to Cal second time since Yankovic's Poly, [San Luis] wasn't as tidy," graduating, isn't just (ARCH '80) he says Wistfully. "It had its funny riding around in the reputation for quirks and character to it. Like the back of a big, fancy manic craziness ['uniquely' decorated] bathrooms car.