We Make Carpets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T Hof Duno (Walcherse Archeologische Rapporten

Van Duinhoofd tot Duno. Historisch, bouwhistorisch, geofysisch en archeologisch onderzoek naar ‘t Hof Duno te Oostkapelle, gemeente Veere. B. Silkens (red.) met bijdragen van P. Blom, P.A. Henderikx, R.H.M. van Immerseel, Vlaardingerbroek & Wevers, D. Wilbourn en J. Zwemer Walcherse Archeologische Rapporten 22 Colofon Van Duinhoofd tot Duno. Historisch, bouwhistorisch, geofysisch en archeologisch onderzoek naar ‘t Hof Duno te Oostkapelle, gemeente Veere. Walcherse Archeologische Rapporten 22 WAD-Projectcode VEOO-09-008 Redactie B. Silkens Met bijdragen van P. Blom, P. Henderikx, R.H.M. van Immerseel, Vlaardingerbroek & Wevers, D. Wilbourn en J. Zwemer Afbeeldingen WAD tenzij anders vermeld Autorisatie—B.H.F.M. Meijlink Uitgegeven door Walcherse Archeologische Dienst Postbus 70 4330 AB Middelburg Tel: 0118-67 88 03 Fax: 0118-62 80 94 e-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978-90-78877-29-5 Domburg, 2011 Omslag Het hof Duynhove (Duno) op de kaart van de gebroeders Hattinga, ca. 1750 Bron: Zeeuws Archief © Walcherse Archeologische Dienst, juni 2011 Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden vermenigvuldigd en/of openbaar gemaakt worden door middel van druk, fotokopie of op welke andere wijze dan ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. De WAD aanvaardt geen aansprakelijkheid voor eventuele schade voortvloeiend uit de toepassing van de adviezen of het gebruik van de resultaten van dit onderzoek. Inhoud Samenvatting 4 Administratieve gegevens 5 1 Inleiding - B. Silkens 6 1.1 Aanleiding van het onderzoek 1.2 Ligging van het onderzoeksgebied 1.3 Huidig gebruik en toekomstig gebruik 1.4 Doel van het onderzoek 1.5 Werkwijze 1.6 Bronnen 2 Geologie en bodem - B. -

En Booronderzoek Aan De Duinweg 24 Te Oostkapelle, Gemeente Veere

Archeologisch bureau- en booronderzoek aan de Duinweg 24 te Oostkapelle, gemeente Veere Walcherse Archeologische Dienst Walcherse Archeologische Briefrapporten 12 Colofon Archeologisch bureau- en booronderzoek aan de Duinweg 24 te Oostkapelle, gemeente Veere Walcherse Archeologische Briefapporten 12 WAD-Projectcode VEOO_015_005 Auteur B. Silkens Afbeeldingen WAD tenzij anders vermeld Autorisatie—B.H.F.M. Meijlink Uitgegeven door Walcherse Archeologische Dienst Postbus 70 4330 AB Middelburg Tel: 0118-67 88 03 Fax: 0118-62 80 94 e-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978-90-78877-49-3 Domburg, 2015 Omslag Oostkapelle en de Duinweg op de bodemkaart van Bennema en Van der Meer. Bron: Zeeuws Archief. © Walcherse Archeologische Dienst, september 2015 Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden vermenigvuldigd en/of openbaar gemaakt worden door middel van druk, fotokopie of op welke andere wijze dan ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. De WAD aanvaardt geen aansprakelijkheid voor eventuele schade voortvloeiend uit de toepassing van de adviezen of het gebruik van de resultaten van dit onderzoek. Administratieve gegevens Soort onderzoek: Inventariserend Veldonderzoek met grondboringen Provincie: Zeeland Gemeente: Veere Plaats: Oostkapelle Toponiem: Duinweg 24 Centrumcoörd. onderzoeksgebied: X: 27879 / Y: 399335 Oppervlakte plan/onderzoeksgebied: ca. 1526 m2 Kadaster: percelen H 823 & 1044 CIS-code. Archis II: 3973264100 Opdrachtgever: Gemeente Veere dhr. J. Muizelaar Postbus 3000 4380 GV Vlissingen (0118) 487 000 Bevoegd gezag: Gemeente Veere Namens deze: B.H.F.M. Meijlink Walcherse Archeologische Dienst (WAD) Postbus 6000 4330 LA Middelburg e-mail: [email protected] Beheer en plaats van documentatie: Zeeuws Archeologisch Archief (ZAA) Stichting Cultureel Erfgoed Zeeland (SCEZ) Postbus 49, 4330 AA Middelburg Beheerder: dhr. -

Information Vlissingen

magazineinformation Vlissingen N K E E T E I N N R D G E N N E I E H T C E A N L A L R E I O T N H O amadore.nl Lees mij Read me lies mich 2 | amadore.nl 04 33 Hotel Zeeland Practical information about Where each village is no further than 17 km Hotel Arion with answers from the sea or from a dammed inlet. to frequent questions. With the coast and unique hinterland Amadore Exclusive Collection Amadore Exclusive around you, there is always something to see: beaches and dunes, dikes, mud Content 16 flats and salt marshes, mounds and wetland areas. Amadore offers hotels and restaurants in the most beautiful Restaurant spots, with Zeeland as a unique backdrop. Our restaurant. There are plenty of opportunities to discover the history and diversity of 22 nature in Zeeland during your stay. A-thermen 48 Wellness without limits! Our beautiful renovated Thermal Baths is a paradise for all sauna lovers. With a variation of Amadore Amadore is proud of Zeeland. sauna’s, several swimming pools, The atmosphere, conviviality and an extensive wellness garden and an personality of this province fit perfectly experience program with great with the foundations of our companies. relaxation areas, we can say that At the most beautiful locations in the this unique spa is complete! province - in Goes, Middelburg, Kamperland, Domburg, Dishoek and Vlissingen - we work day and night to reinforce our motto ‘Boundless Hospitality’. With always that beautiful South-West Delta as backdrop. Boulevard Bankert 266 4382AC Vlissingen +31(0)118 - 410 502 [email protected] amadore.nl/arion 3 Dear guest at Amadore Hotel Restaurant Arion, On behalf of the entire team, I would like to welcome you! Thank you for your trust in our boundless hospitality. -

Castaways New Insights from The

Castaways New Insights from the Metal Detected Brooches of Early Medieval Frisia Marcus A Roxburgh Title page and chapter illustrations are adaptations of images from the Julius work calendar now in the British Library, drawn by Marcus A Roxburgh. All illustrations of brooches in this thesis are drawn by Marcus A Roxburgh. [email protected] II Castaways New Insights from the Metal Detected Brooches of Early Medieval Frisia Author: Marcus A. Roxburgh Course: Master Research and Thesis Course code: ARCH 1044WY Student nr: S1182625 Supervisors: dr. H Huisman, prof.dr. A.L van Gijn Specialisations: Material Culture Studies, Field Archaeology University of Leiden, Faculty of Archaeology Leiden, 15th June 2013 III IV TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents Page LIST OF FIGURES X LIST OF TABLES XIII ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS XIV 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 History of research 3 1.1.1 The development of early medieval archaeology 3 1.1.2 The archaeology of early medieval Frisia 4 1.1.3 The study of brooches 7 1.1.4 Metal detecting and 'Productive Sites' 8 1.1.5 The development of compositional analysis and hhXRF 10 1.2 Theoretical orientation 13 1.2.1 Philosophy 13 1.2.2 Memory and Learning 14 1.2.3 Cross Craft Interaction 17 1.2.4 Reuse and Recycling 19 1.3 Problem orientation and research questions 21 2 METHODOLOGY 27 2.1 hhXRF 28 2.1.1 The principles of hhXRF 28 2.1.2 The debate concerning archaeological application 28 2.1.3 The methodology for brooches 30 2.2 Morphological analysis 32 V 2.2.1 The principles of morphological analysis 32 2.2.2 The morphological -

Veere Structuurvisie Domburg

veere structuurvisie domburg veere structuurvisie domburg opdrachtgever : gemeente Veere nummer : 000725.6392.00 datum : 4 juli 2002 opdrachtleider : ir C.A. Louws auteur(s) : ir C.A. Louws ir J.F.M. Taminiau Adviesbureau RBOI 000725.6392.00 Rotterdam / Middelburg Inhoud 1 1. Inleiding blz. 3 1.1. Aanleiding 3 1.2. Doelstelling 3 1.3. Profiel Domburg 4 1.4. Opbouw structuurvisie 6 2. Beleidskader 7 3. Analyse 9 3.1. Ruimtelijke structuur 9 3.2. Functionele analyse 14 3.3. Sterkte-zwakte analyse 19 4. Visie 21 4.1. Uitgangspunten 21 4.2. Ruimtelijke hoofdstructuur 21 5. Inspraak 5.1. Inleiding 27 5.2. Samenvatting en beantwoording inspraakreacties 27 5.3. Ambtshalve aanpassingen 39 Bijlage: 1. Beleidskader 2. Verslag inspraakbijeenkomst (niet in pdf opgenomen, op verzoek verkrijgbaar) 3. Inspraakreacties (niet in pdf opgenomen, op verzoek verkrijgbaar) Adviesbureau RBOI 000725.6392.00 Rotterdam / Middelburg Inhoud 2 Adviesbureau RBOI 000725.6392.00 Rotterdam / Middelburg 1. Inleiding 3 1.1. Aanleiding Na de samenvoeging van de voormalige gemeenten tot de huidige gemeente Veere was het ontwikkelen van een samenhangende ruimtelijke visie op de ontwikkeling van de kernen een belangrijke prioriteit. daarbij is een stapsgewijze benadering gehanteerd. Allereerst is een aan- tal beleidsnota's opgesteld, met als doel richting te geven aan het ruimtelijke beleid van de nieuwe gemeente. Op 22 april 1999 zijn de volgende nota's vastgesteld door de gemeenteraad: - beleidsoriëntatie kernen; - notitie "profilering /beleidsaccenten kernen"; - notitie “bedrijventerreinen"; - Volkshuisvestingsplan, fase 1; - Woningbouwprogramma 1997 t /m 2006; - notitie "uitgangspunten voor de benutting van het kwaliteitscontingent". Voorts is op 3 juni 1999 de notitie "omschrijving van de identiteit van de gemeente Veere en de daaruit voortvloeiende beleidsprioriteiten" vastgesteld door de gemeenteraad. -

Een Archeologische Opgraving Aan De Brouwerijstraat 36B Te Oostkapelle, Gemeente Veere

Een archeologische opgraving aan de Brouwerijstraat 36b te Oostkapelle, gemeente Veere. Walcherse Archeologische Dienst Walcherse Archeologische Rapporten 26 Colofon Archeologische opgraving aan de Brouwerijstraat te Oostkapelle, gemeente Veere. Walcherse Archeologische Rapporten 26 WAD-Projectcode VEDO-010-009 Auteur B. Silkens & A.H.E. Mostert Afbeeldingen WAD tenzij anders vermeld Autorisatie—B.H.F.M. Meijlink Uitgegeven door Walcherse Archeologische Dienst Postbus 70 4330 AB Middelburg Tel: 0118-67 88 03 Fax: 0118-62 80 94 e-mail: [email protected] ISBN: 978-90-78877-24-0 Domburg, 2010 Omslag Overzichtsfoto van de aanleg van werkput 1 door de WAD © Walcherse Archeologische Dienst, oktober 2010 Niets uit deze uitgave mag worden vermenigvuldigd en/of openbaar gemaakt worden door middel van druk, fotokopie of op welke andere wijze dan ook zonder voorafgaande schriftelijke toestemming van de uitgever. De WAD aanvaardt geen aansprakelijkheid voor eventuele schade voortvloeiend uit de toepassing van de adviezen of het gebruik van de resultaten van dit onderzoek. Inhoud Administratieve gegevens 2 Inleiding 5 2.1 Aanleiding van het onderzoek 2.2 Ligging van het onderzoeksgebied 2.3 Huidig gebruik en toekomstig gebruik 2.4 Doel van het onderzoek 2.5 Werkwijze 3 Geologie en bodem 9 4 Archeologie 11 4.1 Onderzoeksgeschiedenis 4.2 Bekende archeologische en historische waarden 5 Resultaten archeologisch veldonderzoek 13 5.1 Inleiding en methode 5.2 Stratigrafie 5.3 Sporen en structuren 6 Uitwerking vondstmateriaal 17 6.1 Aardewerk 6.2 Dierlijk -

W a L C H E R E N 10 1

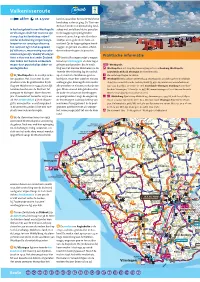

Valkenisseroute 48 km ca. 2,5 uur land in, waardoor het oude Walcherse landschap verloren ging. De ‘Tuin van Zeeland’ kende een kleinschalig land- In het kustgebied tussen Westkapelle schap met ontelbare kleine percelen. en Vlissingen drukt het toerisme zijn In de laaggelegen poelgronden stempel op het landschap: vrijwel waren de percelen gescheiden door zonder onderbreking volgen bunga- slootjes en in gebruik als hooi- en lowparken en campings elkaar op. weiland. Op de hoger gelegen kreek- Een rustpunt ligt in het bosgebied ruggen, in gebruik als akker, scheid- Het strand bij Domburg bij Valkenisse, waar weinig recreatie- den meidoornhagen de percelen. voorzieningen zijn. Voorbij Vlissingen fietst u door een heel ander Zeeland: ∞ Voorbij Vlissingen volgt u wegen Praktische informatie daar leiden met bomen omzoomde boven op kreekruggen en door lager wegen door grootschalige akker- en gelegen poelgronden. Bij de inrich- Ss Westkapelle. weidegebieden. ting van het nieuwe Walcheren na de .p Westkapelle in het dorp. Bij duinovergangen tussen Domburg, Westkapelle, Tweede Wereldoorlog lag de nadruk Zoutelande, Dishoek, Vlissingen (meestal betaald). ¡ Bij Westkapelle is de kustlijn in be- op de moderne landbouw: grotere .i De route loopt tegen de klok in. ton gegoten. Het is een van de vier bedrijven, meer dan 1200 km nieuwe .h Westkapelle Dijkpaviljoen De Westkaap, Westkappelse Zeedijk 7, 4361 SJ (noordzijde plaatsen waar de geallieerden bij de watergangen, drainagebuizen onder dorp). Brasserie-Vistaria De Fontein, Markt 73, 4361 AE, www.brasseriedefontein.nl Slag om Walcheren in 1944 de zeedijk alle percelen en nieuwe, verharde we- (jul.-aug. dagelijks, zie verder de site). Zoutelande. Vlissingen. Domburg Pannenkoe- bombardeerden om de Duitsers tot gen. -

Duinen Als Waterkering Inventarisatie Van Kennisvragen Bij Waterschappen, Provincies En Rijk Oktober 2008

Duinen als Waterkering Inventarisatie van kennisvragen bij waterschappen, provincies en rijk oktober 2008 Opdrachtgever: Rijkswaterstaat - Waterdienst Duinen als Waterkering Inventarisatie van kennisvragen bij waterschappen, provincies en rijk Marien Boers Rapport H5019.10 Duinen als Waterkering H5019.10 oktober 2008 Inhoud 1 Duinen als waterkering.......................................................................................1 1.1 Haalbaarheidsonderzoek voor een nieuw duintoetsinstrumentarium .........................................................................1 1.2 Doelstelling van het rapport......................................................................2 1.3 Structuur van het rapport..........................................................................2 2 Bestuursverantwoordelijkheid duingebieden..................................................4 2.1 Rijk ............................................................................................................4 2.1.1 Landelijk beleid duingebieden......................................................4 2.1.2 Beleidsterrein waterkering tegen overstromingen .......................4 2.1.3 Andere beleidsterreinen ...............................................................6 2.2 Provincies .................................................................................................7 2.2.1 Toezicht op de waterkeringbeheerders........................................7 2.2.2 Bestuurlijk overleg in de regio......................................................8 2.2.3 -

67Th International Sachsensymposion

67th International Sachsensymposion Arbeitsgemeinschaft zur Archäologie der Sachsen und ihrer Nachbarvölker in Nordwesteuropa – IvoE Antwerp, 17th-21st of September 2016 Early medieval waterscapes. Risks and opportunities for (im)material cultural exchange 1 67th International Sachsensymposion Antwerp 2 67th International Sachsensymposion Antwerp IMPRESSUM - IMPRESSUM EDITOR/HERAUSGEBER Rica Annaert (Flemish Heritage Agency/ Agentur für das Kulturerbe Flanderns) CONFERENCE BINDER/TAGUNGSMAPPE Texts Field Trip/ Texte Exkursion : Robert van Dierendonck (Zeeland Foundation for Cultural Heritage), Pieterjan Deckers & Dries Tys (Free University Brussels - VUB). Design and realization/Layout und Umsetzung: Rica Annaert CONFERENCE OFFICE/TAGUNGSBÜRO Gerda Vercammen (City of Antwerp/Stadt Antwerpen) Rone Fillet (Free University Brussels – VUB) SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE/WISSENSCHAFTLICHES KOMITEE Rica Annaert Dries Tys Johan Veeckman Tim Bellens Pieterjan Deckers Robert van Dierendonck Luc Van Impe Laurent Verslype Wim De Clercq Frans Theuws THANKS FOR THE SUPPORT TO/DANK FÜR UNTERSTÜTZUNG AN Flemish Heritage Agency/ Agentur für das Kulturerbe Flanderns City of Antwerp/Stadt Antwerpen Free University Brussels/Freie Universität Brüssel (VUB) Zeeland Foundation for Cultural Heritage/Zeeland Stiftung für das Kulturerbe CONFERENCE LOGO Figurehead of an early medieval ship (late 4th-5th century AD) found in the Scheldt near Appels (prov. of East-Flanders) – ©OE – drawing M. Van Meenen. 3 67th International Sachsensymposion Antwerp A. Felix pakhuis, Oude Leeuwenrui 29: congress venue & conference bureau/ Vortragssaal &Tagungsbüro B. Antwerp City Hall/Rathaus Antwerpen C. Royal Palace on the Meir/Königspalastes auf der Meir. D. Central Railway Station/Hauptbahnhof (Antwerpen Centraal) 4 67th International Sachsensymposion Antwerp PROGRAMME - PROGRAMM All lectures will take place in the auditorium of the Felix Pakhuis, Oudeleeuwenrui 29 (main entrance), 2000 Antwerp. -

Everything You Should Know About Zeeland Provincie Zeeland 2

Provincie Zeeland History Geography Population Government Nature and landscape Everything you should know about Zeeland Economy Zeeland Industry and services Agriculture and the countryside Fishing Recreation and tourism Connections Public transport Shipping Water Education and cultural activities Town and country planning Housing Health care Environment Provincie Everything you should know about Zeeland Provincie Zeeland 2 Contents History 3 Geography 6 Population 8 Government 10 Nature and landscape 12 Economy 14 Industry and services 16 Agriculture and the countryside 18 Fishing 20 Recreation and tourism 22 Connections 24 Public transport 26 Shipping 28 Water 30 Education and cultural activities 34 Town and country planning 37 Housing 40 Health care 42 Environment 44 Publications 47 3 History The history of man in Zeeland goes back about 150,000 brought in from potteries in the Rhine area (around present-day years. A Stone Age axe found on the beach at Cadzand in Cologne) and Lotharingen (on the border of France and Zeeuwsch-Vlaanderen is proof of this. The land there lies for Germany). the most part somewhat higher than the rest of Zeeland. Many Roman artefacts have been found in Aardenburg in A long, sandy ridge runs from east to west. Many finds have Zeeuwsch-Vlaanderen. The Romans came to the Netherlands been made on that sandy ridge. So, you see, people have about the beginning of the 1st century AD and left about a been coming to Zeeland from very, very early times. At Nieuw- hundred years later. At that time, Domburg on Walcheren was Namen, in Oost- Zeeuwsch-Vlaanderen, Stone Age arrowheads an important town. -

Gemeentebeschrijving Domburg

monumenten inventarisatie project Zeeland gemeentebeschrijving WESTEftSCHELDE domburg (1994) B.l. Sens INHOUDSOPGAVE Blz. VOORWOORD 5 1. INLEIDING 7 2. BODEMGESTELDHEID EN GRONDGEBRUIK 7 3. INFRASTRUCTUUR 8 3.1 Wegen 8 3.2 Waterwegen en schuitveren 9 3.3. Tramlijnen 9 4. NEDERZETTINGEN 9 4.1. Functionele ontwikkelingen 9 4.1.1 Recreatie en industrie 9 4.1.2 Energievoorziening 10 4.1.3 P.T.T 10 4.1.4 Bijzondere voorzieningen 10 4.2. Ontwikkeling per nederzetting 12 4.2.1 Domburg 12 4.2.2 Oostkapelle 14 4.2.3 Buitengebied 14 5. GEBIEDEN MET BIJZONDERE WAARDEN IN DE KERN DOMBURG .... 16 LITERATUURLIJST ADRESLIJST VAN GEÏNVENTARISEERDE OBJECTEN EN COMPLEXEN TYPOLOGIE AFBEELDINGEN H0479110.8 - 5 - VOORWOORD Wat is het Monumenten Inventarisatie Project? Door het rijk is in samenwerking met de provincies en de vier grote steden een project ontwikkeld dat als doel heeft de inventarisatie van jonge bouwkunst en stedebouw in Nederland. "Jonge" betekent hier: tot stand gekomen in de periode midden 19e eeuw - Tweede Wereldoorlog. De verkregen gegevens worden landelijk verzameld en verwerkt. Ze kunnen dienen als uitgangspunt voor verder onderzoek en voor het te voeren beleid van rijk, provincies en gemeenten. Ze bestaan uit regio- en gemeentebeschrijvingen en uit de inventarisatieresultaten (veldwerk). Regiobeschrijving De inventarisatie wordt per provincie (of grote stad) gebiedsgewijs aangepakt. Daartoe is de provincie Zeeland in drie werkgebieden verdeeld, namelijk Midden- Zeeland, Noord-Zeeland en Zeeuwsch-Vlaanderen. Per gebied wordt eerst een regiobeschrijving gemaakt, met daarin een beschrij- ving van de historische en ruimtelijke ontwikkelingen in de periode ca. 1850 - 1945 . Bij de beschrijving wordt globaal aandacht besteed aan de algemeen histo- rische aspecten van bestuurlijke, landschappelijke, sociaal-economische en geo- grafische aard. -

De Bodemkartering Van Walcheren

STICHTING VOOR BODEM KARTERING / WAGENINGEN DE BODEMKARTERING VAN WALCHEREN WITH A SUMMARY: SOIL SURVEY OF THE ISLAND OF WALCHEREN Ir J. BENNEMA en Dr Ir K. VAN DER MEER MET MEDEWERKING VAN Ir C. DORSMAN en P. J. VAN DER FEEN STAATSDRUKKERIJ %gnf^ UITGEVERIJBEDRIJF VERSL. LANDBOUWK. ONDERZ. No. 58.4 / 'S-GRAVENHAGE / 1952 utta INHOUD WOORD VOORAF Blz. I. INLEIDING 3 II. GENESE 23 1. De diepere ondergrond van Walcheren 23 2. De oude zeeklei 24 3. Begin van de veenvorming 24 4. De veenvorming 26 5. De hoogteligging van het veenlandschap aan het eind van de veentijd ... 28 6. De bewoning van het veen in Noord-Walcheren 29 7. De eerste opslibbing (de vroeg-Romeinse transgressie) 30 8. De Romeinse regressie 31 9. De vroeg-middeleeuwse transgressie 33 10. De tweede phase van de vroeg-middeleeuwse transgressie 35 11. De Karolingische regressie 37 12. De post-Karolingische transgressie 38 13. De afzettingen uit de post-Karolingische transgressieperiode 39 14. Erosiekreekjes 40 15. De tijd van de bedijkingen 41 16. De belangrijkste anthropogene veranderingen van het Oude-Land en het Middel land 41 17. De vorming van de jonge polders „Het Nieuwland" 42 18. De duinvorming 45 III. BESCHRIJVING VAN DE BODEMTYPEN 47 1. Inleiding 47 2. Oude-Landgronden 47 3. Middellandgronden 54 4. Nieuwlandgronden 59 5. Enkele voorbeelden van groeiverschillen in het Nieuwland 63 6. Vervlogen duinzandgronden 66 IV. ENKELE OPMERKINGEN OVER DE WATERREGELING VAN WALCHEREN, MEDE GEZIEN IN VERBAND MET DE LANDBOUW 68 V. DE BESCHRIJVING VAN DE BODEMKAART 71 A. De bredere kreekruggen 71 1. De kreekrug van Oostkapelle—Serooskerke—Middelburg 73 2.