The Parable of the Prodigal Son in the Fiction of Elizabeth Gaskell

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iraqi Literary Response to the US Occupation

Countering the Sectarian Metanarrative: Iraqi Literary Response to the US Occupation Chad Day Truslow Waynesboro, Virginia B.A. in International Relations & History, Virginia Military Institute, 2008 M.A. in Business Administration, Liberty University, 2014 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of Middle Eastern and South Asian Languages and Cultures University of Virginia December, 2019 1 Abstract Sectarian conflict is a commonly understood concept that has largely shaped US foreign policy approach to the region throughout the modern Middle East. As a result of the conflict between Shia and Sunni militias in Iraq and the nature of Iraqi politics since 2003, many experts have accepted sectarianism as an enduring phenomenon in Iraq and use it as a foundation to understand Iraqi society. This paper problematizes the accepted narrative regarding the relevance of sectarian identity and demonstrates the fallacy of approaching Iraq through an exclusively “sectarian lens” in future foreign policy. This paper begins by exploring the role of the Iraqi intellectuals in the twentieth century and how political ideologies influenced and replaced traditional forms of identity. The paper then examines the common themes used by mid-twentieth century Iraqi literati to promote national unity and a sense of Iraqi identity that championed the nation’s heterogeneity. The paper then surveys the Iraqi literary response to the 2003 invasion in order to explain how some of the most popular Iraqi writers represent sectarianism in their works. The literary response to the US invasion and occupation provides a counter- narrative to western viewpoints and reveals the reality of the war from the Iraqi perspective. -

Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic

Please do not remove this page Giving Evil a Name: Buffy's Glory, Angel's Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic Croft, Janet Brennan https://scholarship.libraries.rutgers.edu/discovery/delivery/01RUT_INST:ResearchRepository/12643454990004646?l#13643522530004646 Croft, J. B. (2015). Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic. Slayage: The Journal of the Joss Whedon Studies Association, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.7282/T3FF3V1J This work is protected by copyright. You are free to use this resource, with proper attribution, for research and educational purposes. Other uses, such as reproduction or publication, may require the permission of the copyright holder. Downloaded On 2021/10/02 09:39:58 -0400 Janet Brennan Croft1 Giving Evil a Name: Buffy’s Glory, Angel’s Jasmine, Blood Magic, and Name Magic “It’s about power. Who’s got it. Who knows how to use it.” (“Lessons” 7.1) “I would suggest, then, that the monsters are not an inexplicable blunder of taste; they are essential, fundamentally allied to the underlying ideas of the poem …” (J.R.R. Tolkien, “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics”) Introduction: Names and Blood in the Buffyverse [1] In Joss Whedon’s Buffy the Vampire Slayer (1997-2003) and Angel (1999- 2004), words are not something to be taken lightly. A word read out of place can set a book on fire (“Superstar” 4.17) or send a person to a hell dimension (“Belonging” A2.19); a poorly performed spell can turn mortal enemies into soppy lovebirds (“Something Blue” 4.9); a word in a prophecy might mean “to live” or “to die” or both (“To Shanshu in L.A.” A1.22). -

Preservation and Progress in Cranford

Preservation and Progress in Cranford Katherine Leigh Anderson Lund University Department of English ENGK01 Bachelor Level Degree Essay Christina Lupton May 2009 1 Table of Contents I. Introduction and Thesis.................................................. 3 II. Rejection of Radical Change in Cranford...................... 4 III. Traditional Modes of Progress....................................... 11 IV. Historical Transmission Through Literature.................. 14 V. Concluding Remarks....................................................... 18 VI. Works Cited...................................................................... 20 2 Introduction and Thesis Elizabeth Gaskell's Cranford was first published between 1851 and 1853 as a series of episodic stories in Household Words under the the editorship of Charles Dickens; it wasn't until later that Cranford was published in single volume book form. Essentially, Cranford is a collection of stories about a group of elderly single Victorian ladies and the society in which they live. As described in its opening sentence, ”In the first place, Cranford is in possession of the Amazons; all the holders of houses, above certain rent, are women” (1). Cranford is portrayed through the eyes of the first person narrator, Mary Smith, an unmarried woman from Drumble who visits Cranford occasionally to stay with the Misses Deborah and Matilda Jenkyns. Through Mary's observations the reader becomes acquainted with society at Cranford as well as Cranfordian tradition and ways of life. Gaskell's creation of Cranford was based on her own experiences growing up in the small English town of Knutsford. She made two attempts previous to Cranford to document small town life based on her Knutsford experiences: the first a nonfiction piece titled ”The Last Generation” (1849) that captured her personal memories in a kind of historical preservation, the second was a fictional piece,”Mr. -

Adult Fiction Adult Fiction

A Book A Book Inspired by Inspired by Another Another Literary Work Literary Work Adult Fiction Adult Fiction • The Great Night by Chris Adrian • The Great Night by Chris Adrian • Flaubert's Parrot by Julian Barnes • Flaubert's Parrot by Julian Barnes • 2666 by Roberto Bolaño • 2666 by Roberto Bolaño • March by Geraldine Brooks • March by Geraldine Brooks • The Master and Margarita • The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov by Mikhail Bulgakov • Foe by J.M. Coetzee • Foe by J.M. Coetzee • Love in Idleness by Amanda Craig • Love in Idleness by Amanda Craig • The Hours by Michael Cunningham • The Hours by Michael Cunningham • Something Rotten by Jasper Fforde • Something Rotten by Jasper Fforde • Bridget Jones Diary by Helen Fielding • Bridget Jones Diary by Helen Fielding • Pride, Prejudice, and Cheese Grits • Pride, Prejudice, and Cheese Grits by Mary Jane Hathaway by Mary Jane Hathaway • Brave New World by Aldous Huxley • Brave New World by Aldous Huxley • Ulysses by James Joyce • Ulysses by James Joyce • Lavinia by Ursula LeGuin • Lavinia by Ursula LeGuin • Juliet’s Nurse by Lois Leveen • Juliet’s Nurse by Lois Leveen • Frankenstein: Prodigal Son • Frankenstein: Prodigal Son by Dean Koontz by Dean Koontz • Wicked by Gregory Maguire • Wicked by Gregory Maguire • Emma by Alexander McCall Smith • Emma by Alexander McCall Smith • Fool by Christopher Moore • Fool by Christopher Moore • Romeo and/Juliet by Ryan North • Romeo and/Juliet by Ryan North • Prospero’s Daughter by Elizabeth Nunez • Prospero’s Daughter by Elizabeth Nunez • Boy, -

ANÁLISIS DE TRADUCCIÓN DE CRANFORD DE ELIZABETH GASKELL Marina Alonso Gómez

Máster Traducción Especializada Universidad de Córdoba ANÁLISIS DE TRADUCCIÓN DE CRANFORD DE ELIZABETH GASKELL Marina Alonso Gómez Trabajo Fin de Máster 2013-2014 Tutora: Dra. Ángeles García Calderón ÍNDICE 0. INTRODUCCIÓN … 3 Justificación … 3 Estructura … 5 1. LA NOVELA SOCIAL INGLESA EN EL SIGLO XIX: CHARLES DICKENS, BENJAMIN DISRAELI Y CHARLES KINGSLEY … 8 1.1 Charles Dickens: su figura y su obra … 12 1.2 Benjamin Disraeli: su figura y su obra … 31 1.3 Charles Kingsley: su figura y su obra … 42 2. ELIZABETH GASKELL … 54 2.1 Su figura y su producción literaria … 54 2.1.1 Cranford … 65 2.1.1.1 Recepción de la obra … 67 3. CRANFORD TRADUCIDA AL ESPAÑOL Y AL FRANCÉS … 76 3.1 Ediciones de la obra … 76 3.1.1 Traducción española y francesa: los traductores … 78 3.1.2 Presencia del traductor … 82 3.1.3 Aspectos culturales … 83 3.1.3.1 Antropónimos … 83 3.1.3.2 Topónimos … 84 3.1.3.3 Personajes … 87 3.1.3.4 Reino animal … 87 3.1.3.5 Gastronomía … 88 3.1.3.6 Indumentaria … 90 3.1.3.7 Esparcimiento … 92 3.1.3.8 Medios de transporte … 93 1 3.1.3.9 Hogar … 94 3.1.3.10 Tratamientos … 95 3.1.3.11 Unidades de media y peso … 97 3.1.4 Aspectos lingüísticos … 98 3.1.4.1 Interjecciones y onomatopeyas … 98 3.1.4.2 Elementos ortotipográficos … 98 3.1.4.3 Extranjerismos … 100 3.1.4.4 Idiolectos … 102 3.1.4.5 Metáforas … 105 3.1.4.6 Modismos … 106 3.1.5 Omisiones, adiciones y alteraciones … 108 3.1.5.1 Omisiones … 108 3.1.5.2 Adiciones … 108 3.1.5.3 Alteraciones … 109 3.1.5 Otros errores … 111 3.1.5.1 De sentido … 111 3.1.5.1.1 Términos aislados … 111 3.1.5.1.2 Estructuras complejas … 112 3.1.5.2 De sintaxis … 120 3.1.6 Traducción francesa … 123 CONCLUSIONES … 125 BIBLIOGRAFÍA … 129 Diccionarios utilizados … 135 2 0. -

Buffy & Angel Watching Order

Start with: End with: BtVS 11 Welcome to the Hellmouth Angel 41 Deep Down BtVS 11 The Harvest Angel 41 Ground State BtVS 11 Witch Angel 41 The House Always Wins BtVS 11 Teacher's Pet Angel 41 Slouching Toward Bethlehem BtVS 12 Never Kill a Boy on the First Date Angel 42 Supersymmetry BtVS 12 The Pack Angel 42 Spin the Bottle BtVS 12 Angel Angel 42 Apocalypse, Nowish BtVS 12 I, Robot... You, Jane Angel 42 Habeas Corpses BtVS 13 The Puppet Show Angel 43 Long Day's Journey BtVS 13 Nightmares Angel 43 Awakening BtVS 13 Out of Mind, Out of Sight Angel 43 Soulless BtVS 13 Prophecy Girl Angel 44 Calvary Angel 44 Salvage BtVS 21 When She Was Bad Angel 44 Release BtVS 21 Some Assembly Required Angel 44 Orpheus BtVS 21 School Hard Angel 45 Players BtVS 21 Inca Mummy Girl Angel 45 Inside Out BtVS 22 Reptile Boy Angel 45 Shiny Happy People BtVS 22 Halloween Angel 45 The Magic Bullet BtVS 22 Lie to Me Angel 46 Sacrifice BtVS 22 The Dark Age Angel 46 Peace Out BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part One Angel 46 Home BtVS 23 What's My Line, Part Two BtVS 23 Ted BtVS 71 Lessons BtVS 23 Bad Eggs BtVS 71 Beneath You BtVS 24 Surprise BtVS 71 Same Time, Same Place BtVS 24 Innocence BtVS 71 Help BtVS 24 Phases BtVS 72 Selfless BtVS 24 Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered BtVS 72 Him BtVS 25 Passion BtVS 72 Conversations with Dead People BtVS 25 Killed by Death BtVS 72 Sleeper BtVS 25 I Only Have Eyes for You BtVS 73 Never Leave Me BtVS 25 Go Fish BtVS 73 Bring on the Night BtVS 26 Becoming, Part One BtVS 73 Showtime BtVS 26 Becoming, Part Two BtVS 74 Potential BtVS 74 -

The Prodigal Father

"There was a man who had two sons..." - LUKE 15:11 THE PRODIGAL FATHER LUKE 15:11-24 NOVEMBER 29, 2020 TRADITIONAL SERVICE 10:30 AM TRADITIONAL WORSHIP SERVICE NOVEMBER 29 • THE FIRST SUNDAY OF ADVENT Welcome! Are you new at Christ Church? Please stop by our Welcome Welcome to worship. To care for one another, we ask that those seated in the mask-only section keep their face Table in the Gathering Hall or coverings on throughout the service, and we are refraining from singing aloud during this season. Children may Family Life Center Lobby to pick up a take-home activity packet on the tree in the landing for use in worship and afterwards. learn more about our church and how to get involved. Worship with us safely outdoors at Constellation Field on Christmas Eve! All are invited to stay afterward and enjoy the Holiday Lights as our guests. PRELUDE DOXOLOGY We offer two worship services Masks will be required as you enter and exit. Space is limited! Bring a Torch, Jeanette, Isabella Angels We Have Heard On High each Sunday morning, both at We will also worship in our Sanctuary at 12 pm and 8 pm on Christmas Eve. arr. Heather Sorenson 10:30 am. Preaching today are: Seating will be limited, and masks will be required for the indoor services. BETH McCONNELL SCRIPTURE READING TRADITIONAL SERVICE IN THE SANCTUARY Reserve your seats for our Christmas Eve services at christchurchsl.org/christmas. Luke 15:11-24 *GREETING & LIGHTING OF Pastor R. Deandre Johnson THE ADVENT CANDLE CONTEMPORARY SERVICE OUR ADVENT SERMON SERIES: SERMON IN COVENANT HALL *OPENING HYMNS "The Prodigal Son" Pastor C. -

Contextualizing Value: Market Stories in Mid-Victorian Periodicals By

Contextualizing Value: Market Stories in Mid-Victorian Periodicals By Emily Catherine Simmons A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of English University of Toronto © Copyright Emily Catherine Simmons 2011 Abstract Contextualizing Value: Market Stories in Mid-Victorian Periodicals Emily Catherine Simmons Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of English, University of Toronto Copyright 2011 This dissertation examines the modes, means, and merit of the literary production of short stories in the London periodical market between 1850 and 1870. Shorter forms were often derided by contemporary critics, dismissed on the assumption that quantity equals quality, yet popular, successful, and respectable novelists, namely Charles Dickens, Anthony Trollope, Elizabeth Gaskell and Margaret Oliphant, were writing, printing, and distributing them. This study navigates a nexus of discourses about culture, literature, and writing to explore, delineate, and ascertain the implications of the contextual position of certain short stories. In particular, it identifies and characterizes a previously unexamined genre, here called the Market Story, in order to argue for the contingency and de-centring of processes and pronouncements of valuation. Market stories are defined by their relationship to a publishing industry that was actively creating a space for, demanding, and disseminating texts based on their potential to generate sales figures, draw attention to a particular organ, -

Orthros on Sunday, February February February 28, 2016; Tone 6 / Eothinon 6 Sunday of the Prodigal Son Sunday of the Prodigal So

Orthros ononon SundaySunday,, February 22282888,, 2012016666;; Tone 666 / Eothinon 666 Sunday of the Prodigal Son Venerable Basil the Confessor, companion of Prokopios of Decapolis; Hieromartyr Proterios, archbishop of Alexandria; Righteous Kyra and Marana of Beroea in Syria; Apostles Nymphas and Euvoulos; New-martyr Kyranna of Thessalonica Priest: Blessed is our God always, now and ever, and unto ages of ages. Choir: Amen. People: Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal: have mercy on us. (THRICE) Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit; both now and ever, and unto ages of ages. Amen. All-holy Trinity, have mercy on us. Lord, cleanse us from our sins. Master, pardon our iniquities. Holy God, visit and heal our infirmities for Thy Name’s sake. Lord, have mercy. (THRICE) Glory to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Spirit; both now and ever, and unto ages of ages. Amen. Our Father, Who art in Heaven, hallowed be Thy Name. Thy kingdom come; Thy will be done on earth as it is in Heaven. Give us this day our daily bread; and forgive us our trespasses, as we forgive those who trespass against us, and lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. Priest: For Thine is the kingdom, and the power, and the glory: of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit; now and ever, and unto ages of ages. Choir: Amen. (Choir continues.) O Lord, save Thy people and bless Thine inheritance, granting to Thy people victory over all their enemies, and by the power of Thy Cross preserving Thy commonwealth. -

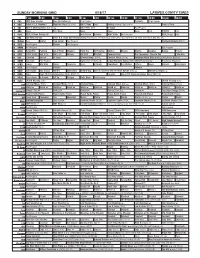

Sunday Morning Grid 6/18/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/18/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Celebrity Paid Program 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Sailing America’s Cup. (N) Å Track & Field 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid XTERRA Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday 2017 U.S. Open Golf Championship Final Round. The final round of the 2017 U.S. Open tees off. From Erin Hills in Erin, Wis. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Northern Borders (2013) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Cooking Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVY) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Concrete River The Carpenters: Close to You Pavlo Live 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Tomorrow Never Dies ››› (1997) Pierce Brosnan. 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho (N) El Que No Corre Vuela (1982) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Película Película 50 KOCE Odd Squad Odd Squad Martha Cyberchase Clifford-Dog Eat Fat, Get Thin With Dr. -

Ann-Kathrin Deininger and Jasmin Leuchtenberg

STRATEGIC IMAGINATIONS Women and the Gender of Sovereignty in European Culture STRATEGIC IMAGINATIONS WOMEN AND THE GENDER OF SOVEREIGNTY IN EUROPEAN CULTURE EDITED BY ANKE GILLEIR AND AUDE DEFURNE Leuven University Press This book was published with the support of KU Leuven Fund for Fair Open Access Published in 2020 by Leuven University Press / Presses Universitaires de Louvain / Universitaire Pers Leuven. Minderbroedersstraat 4, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium). Selection and editorial matter © Anke Gilleir and Aude Defurne, 2020 Individual chapters © The respective authors, 2020 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Non-Derivative 4.0 Licence. Attribution should include the following information: Anke Gilleir and Aude Defurne (eds.), Strategic Imaginations: Women and the Gender of Sovereignty in European Culture. Leuven, Leuven University Press. (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ISBN 978 94 6270 247 9 (Paperback) ISBN 978 94 6166 350 4 (ePDF) ISBN 978 94 6166 351 1 (ePUB) https://doi.org/10.11116/9789461663504 D/2020/1869/55 NUR: 694 Layout: Coco Bookmedia, Amersfoort Cover design: Daniel Benneworth-Gray Cover illustration: Marcel Dzama The queen [La reina], 2011 Polyester resin, fiberglass, plaster, steel, and motor 104 1/2 x 38 inches 265.4 x 96.5 cm © Marcel Dzama. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner TABLE OF CONTENTS ON GENDER, SOVEREIGNTY AND IMAGINATION 7 An Introduction Anke Gilleir PART 1: REPRESENTATIONS OF FEMALE SOVEREIGNTY 27 CAMILLA AND CANDACIS 29 Literary Imaginations of Female Sovereignty in German Romances -

Southern Music and the Seamier Side of the Rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1995 The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Folklore Commons, Music Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hutson, Cecil Kirk, "The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South " (1995). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 10912. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/10912 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthiough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproductioiL In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion.