Iraqi Literary Response to the US Occupation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Adult Fiction Adult Fiction

A Book A Book Inspired by Inspired by Another Another Literary Work Literary Work Adult Fiction Adult Fiction • The Great Night by Chris Adrian • The Great Night by Chris Adrian • Flaubert's Parrot by Julian Barnes • Flaubert's Parrot by Julian Barnes • 2666 by Roberto Bolaño • 2666 by Roberto Bolaño • March by Geraldine Brooks • March by Geraldine Brooks • The Master and Margarita • The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov by Mikhail Bulgakov • Foe by J.M. Coetzee • Foe by J.M. Coetzee • Love in Idleness by Amanda Craig • Love in Idleness by Amanda Craig • The Hours by Michael Cunningham • The Hours by Michael Cunningham • Something Rotten by Jasper Fforde • Something Rotten by Jasper Fforde • Bridget Jones Diary by Helen Fielding • Bridget Jones Diary by Helen Fielding • Pride, Prejudice, and Cheese Grits • Pride, Prejudice, and Cheese Grits by Mary Jane Hathaway by Mary Jane Hathaway • Brave New World by Aldous Huxley • Brave New World by Aldous Huxley • Ulysses by James Joyce • Ulysses by James Joyce • Lavinia by Ursula LeGuin • Lavinia by Ursula LeGuin • Juliet’s Nurse by Lois Leveen • Juliet’s Nurse by Lois Leveen • Frankenstein: Prodigal Son • Frankenstein: Prodigal Son by Dean Koontz by Dean Koontz • Wicked by Gregory Maguire • Wicked by Gregory Maguire • Emma by Alexander McCall Smith • Emma by Alexander McCall Smith • Fool by Christopher Moore • Fool by Christopher Moore • Romeo and/Juliet by Ryan North • Romeo and/Juliet by Ryan North • Prospero’s Daughter by Elizabeth Nunez • Prospero’s Daughter by Elizabeth Nunez • Boy, -

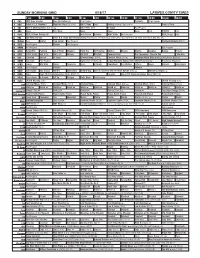

Sunday Morning Grid 6/18/17 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/18/17 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Celebrity Paid Program 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) NBC4 News Paid Sailing America’s Cup. (N) Å Track & Field 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News News News Paid XTERRA Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 11 FOX Fox News Sunday 2017 U.S. Open Golf Championship Final Round. The final round of the 2017 U.S. Open tees off. From Erin Hills in Erin, Wis. (N) 13 MyNet Paid Matter Fred Jordan Paid Program Northern Borders (2013) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Paid Program 22 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 24 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexico Martha Cooking Baking Project 28 KCET 1001 Nights Bali (TVG) Bali (TVY) Edisons Biz Kid$ Biz Kid$ Concrete River The Carpenters: Close to You Pavlo Live 30 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Criminal Minds (TV14) Criminal Minds (TV14) Tomorrow Never Dies ››› (1997) Pierce Brosnan. 34 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Como Dice el Dicho (N) El Que No Corre Vuela (1982) María Elena Velasco. República Deportiva 40 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Jeffress Super Kelinda John Hagee 46 KFTR Paid Program Película Película 50 KOCE Odd Squad Odd Squad Martha Cyberchase Clifford-Dog Eat Fat, Get Thin With Dr. -

American University of Beirut Annual Report of the Faculty of Arts And

AMERICAN UNIVERSITY OF BEIRUT ANNUAL REPORT OF THE FACULTY OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ACADEMIC YEAR 2011-2012 Dr. Peter Dorman President American University of Beirut Beirut, Lebanon March 2013 Dear Mr. President, Please find enclosed the Annual Report of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences for the academic year 2011-2012. This report was written by the chairpersons and/or directors of the academic units and of standing committees of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, and edited in the Arts and Sciences Dean’s Office. Patrick McGreevy Dean of the Faculty TABLE OF CONTENTS Part I Summary Report of the Office of the Dean Dean Patrick McGreevy P. 1 Part II Reports of the Standing Committees Advisory Committee………………………………………. Dean Patrick McGreevy P. 7 Curriculum Committee……………………………………. Dr. Tarek Ghaddar P. 9 Graduate Committee………………………………………. Dr. Sawsan Kreydiyyeh P. 14 Library Committee………………………………………… Dr. Sirene Harb P. 20 Research Committee………………………………………. Dr. Rabih Sultan P. 22 Student Academic Affairs Committee……………………. Dr. Malek Tabbal P. 29 Student Disciplinary Affairs Committee…………………. Dr. Joshua Andresen P. 35 Undergraduate Admissions Committee…………………… Dr. Hans D. Muller P. 38 Part III Reports of the Academic Units Anis Makdessi Program in Literature…………………... Dr. Maher Jarrar P. 46 Arabic and Near Eastern Languages Department………. Dr. Assaad Khairallah P. 49 Biology Department…………………………………….. Dr. Colin Smith P. 63 Center for Arab and Middle Eastern Studies …………… Dr. Waleed Hazbun P. 90 Center for American Studies and Research …………….. Dr. Alex Lubin P. 102 Center for Behavioral Research ……..…………………... Dr. Samir Khalaf P. 108 Center for English Language Research and Teaching …... Dr. Kassim Shaaban P. 112 Chemistry Department ………………………………….. -

{Download PDF} in Odd We Trust Kindle

IN ODD WE TRUST PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dean Koontz | 224 pages | 01 Jul 2008 | HarperCollins Publishers | 9780007236961 | English | London, United Kingdom In Odd We Trust PDF Book Francois Schuiten and Benoit Peeters. I understand Dean Koontz's interest in experimenting with different story telling formats and loo I like the Odd Thomas character and when I saw this graphic novel was intrigued to see how they approached the story. In Odd We Trust 4. The characters were so far removed from their novel counterparts that Odd was barely more than a boy who walked from scene to scene just to tie the story together and for some reason Sto I don't really have much good to say about this graphic novel. Ian Edginton. It doesn't end like Erin Hunter's graphic books where the books are serialized. The characters were so far removed from their novel counterparts that Odd was barely more than a boy who walked from scene to scene just to tie the story together and for some reason Stormy had been turned into an angry gun- toting maniac. I haven't ever read any Dean Koontz novels before, and I have to say that this does not give me the desire to do so. It was awful. Garth Ennis and Jamie Delano. We use cookies to give you the best online experience. Trisha — Jul 02, Picked this up at a used bookstore, and thought "Huh! I've heard of soul mates and stuff which I can understand it to an extent but in this graphic novel I just couldn't get a sense for it. -

International Journal of Language and Literary Studies

International Journal of Language and Literary Studies The Grotesque in Frankenstein in Baghdad: Between Humanity and Monstrosity Volume 2, Issue 1, 2020 Homepage : http://ijlls.org/index.php/ijlls The Grotesque in Frankenstein in Baghdad: Between Humanity and DOIMonstrosity: 10.36892/ijlls.v1i3.71 Rawad Alhashmi The University of Texas at Dallas, USA [email protected] DOI: https://doi.org/10.36892/ijlls.v2i1.120 Received: Abstract 13/01/2020 This paper analyzes Ahmed Saadawi’s Frankenstein in Baghdad (2018) with a special emphasis on the grotesque bodily images of the monster, the novel’s Accepted: 17/03/2020 exploration of justice, and the question of violence. I draw on the theoretical framework of the Russian philosopher and literary critic Mikhail Bakhtin (1895–1975), the ethics philosopher Emmanuel Levinas (1906–1995), and the Keywords: German-American philosopher and political thinker Hannah Arendt (1906– Dystopia; 1975). Saadawi’s unnamed monster, “The Whatsitsname,” comes into being Frankenstein; via an accidental if honorably intentioned act, when the main character, Hadi, Grotesque; Justice; compiles remnant corpses that he finds in the streets of Bagdad into one body Monster; Other; Violence with the aim of conducting “a proper burial” in order to dignify the dead. Interestingly, while the monster is the enemy in the eyes of the Iraqi government, he is a savior for the ordinary people— their only hope of putting an end to the violence and achieving justice. In this paper, I argue that Saadawi draws on the metaphor of Frankenstein’s monster not only to capture the dystopian mood in post-2003 Baghdad, but also to question the tragic realities, and the consequence of war, as well as the overall ramification of colonialism. -

A N N Otated B Ook S R Eceived

A n n otated B ook s R eceived A SUPPLEMENT TO Tran slation R ev iew Volume 23, No. 1–2, 2018 THE UNIVERSITY OF TEXAS AT DALLAS CONTRIBUTORS Linda Snow Stephanie Tamayo Shelby Vincent All correspondence and inquiries should be directed to: Translation Review The University of Texas at Dallas 800 West Campbell Road, JO 51 Richardson, TX 75080-3021 Telephone: 972-883-2093 Fax: 972-883-6303 [email protected] Annota ted B ooks R eceived is a supplement of T ra nsla tion Review, a publication of The Center for Translation Studies at The University of Texas at Dallas. ISSN 0737-4836 Copyright © 2018 by The University of Texas at Dallas The University of Texas at Dallas is an equal opportunity /affirmative action employer. Annotated Books Received — vol. 23.1–2 ANNOTATED BOOKS RECEIVED 23.1 – 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Albanian ............................................................................................................. 1 Arabic .................................................................................................................. 1 Arabic, French, and Dutch …………………………………………………………… 3 Arabic and Persian …………………………………………………………………… 3 Bulgarian……………………………………………………………………..……...… 4 Catalan………………………………………………………………...……………..… 4 Chinese ................................................................................................................. 5 Croatian ................................................................................................................ 6 Czech………………………………………………………………………………..…… 8 Danish………………………………………………………………………………….… -

Frankenstein: the Dead Town: a Novel PDF Book

FRANKENSTEIN: THE DEAD TOWN: A NOVEL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Dean R Koontz | 423 pages | 26 Oct 2012 | Random House USA Inc | 9780553593686 | English | New York, United States Frankenstein: the Dead Town: a Novel PDF Book To see what your friends thought of this book, please sign up. It syncs automatically with your account and allows you to read online or offline wherever you are. Helios has acquired wealth and power from selling his knowledge to, among others, Adolf Hitler , Joseph Stalin , and the People's Republic of China. Our insipid band of idiots, I mean heroes find weird bits of flesh all over the place, some look almost normal and others have weird shit like extra body parts growing out of them. A member of the New Race. Others fainted. Im still upset that this didn't become a movie or series. A little girl in Las Vegas. Opposed to his activities are a pair of homicide detectives and Frankenstein's original monster , now known as Deucalion. I think they also went a little ape-shit in the first two books, Prodigal Son and City of Night. Michael Richan writes it and there are multiple series that all take place within the one universe. A dark memory is calling out to them. Now the master of suspense delivers an unforgettable novel that is at once a thrilling adventure in itself and a mesmerizing conclusion to his saga of the modern monsters among us. Please follow the detailed Help center instructions to transfer the files to supported eReaders. I drug this one out because I am going to miss Deucalion! First, there is Deucalion, Helios original creation. -

A Portrait of the Translator As a Political Activist Abstract

Journal of the College of Arts. University of Basrah No. ( 40 ) 2006 A Portrait of the Translator as a Political Activist Kadhim Ali,(PhD) Asst. Professor of Linguistics and Translation University of Basra [email protected] Abstract This paper attempts to portray the role of the translator as a political activist. It studies the character of the translator Mansur Abd As-Salam in Abd Ar-Rahman Munif's 1973 novel Al-Ashjaar wa Igtiyaal Marzouq (The Trees and the Assassination of Marzouq)1. In addition to emphasizing the sociopolitical characterization of the translator in this important Arabic novel, the paper focuses on the professional context(s) Abd As-Salam is set in and on parallels between the narratives of the author and the character of the translator. The concluding point that the researcher draws is that translation replaces writing and helps to secure a haven for endangered people who indulge in political activism though it is depicted as marginal and secondary as far as the original professions of those people is concerned. Key Words: Translation, Political Activism, Translator's Narrative, Author's Narrative 1. Introduction : The Translator in Fiction The novel can be said to be our best means to understand ourselves and the world through other people being characterized. As the highest form of narrative discourse, it "serves as the model by which society conceives of itself, the discourse in and through which it ( ) Journal of the College of Arts. University of Basrah No. ( 40 ) 2006 articulates the world" (Culler, 1975:189). In taking the argument to its farthest end, Culler contends that word composition will give access to different kinds of models: "…a model of the social world, models of the individual personality, of the relations between the individual and society, and, perhaps most important, of the kind of significance which these aspects of the world can bear" (ibid.). -

Robert James Farley

Robert James Farley UCLA | Department of Comparative Literature 350 Kaplan Hall | University of California | Los Angeles, CA 90095-0001 +1 562 673 2913 (mobile) | [email protected] | www.robertfarley.org EDUCATION Degree Programs 2021 Ph.D., expected Spring, University of California, Los Angeles (2019, Candidacy in Comparative Literature, dissertation title: Virtually Kwīr: Digital Archives of the Sexual Rights Movement in Arabic) 2011 B.A., 2011, California State University, Long Beach (comparative world literature, minors in history and Middle Eastern studies) Arabic Training 2015-16 Center for Arabic Study Abroad (CASA), Qasid Institute, Amman, Jordan 2013-14 Arabic Language Program, University of Jordan and Princess Sumaya University for Technology, Amman, Jordan 2012 Arabic Language Summer Session, Middlebury College, Oakland, California Other Education 2009 Semester Exchange, University of Leicester College of Arts, Humanities, and Law, Leicester, U.K. PUBLICATIONS Book Chapters 2021 “Mahfouz, al-Mutanabbi, and the Canon: Poetics of Deviance in the Masculine Nationalist Discourse of Al-Sukkariyya,” in Constructions of Masculinity in the Middle East and North Africa: Literature, Film, and National Discourse, eds. Mohja Kahf and Nadine Sinno. The American University in Cairo Press, pp. 103-119. Articles 2019 “Phantom Limbs: Socio-Psychic Contours of the Maimed Body in ‘I used to Count my Friends on my Fingers’,” Wordgathering: A Journal of Disability Poetry and Literature, vol. 13, no. 1, March. 2013 “National Allegory and the Parallax View in Tawfiq̄ al-Haḳ im's̄ Masị r̄ Suṛ sạ r̄ ,” Portals: A Journal in Comparative Literature, vol. 10. 2011 “Intellectual Space in Naguib Mahfouz’s Thartharah fawq al-Nil̄ ,” CSULB McNair Scholars Research Journal, vol. -

[email protected] [email protected]

[email protected] [email protected] This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License Norman Fairclough 13 Discourse Analysis of Terrorism in Iraqi novels: A look at Frankenstein in Baghdad Asst. Prof.Dr. Nasser Qasemi - Asst. Prof.Dr. Kamal Baghjari Asst. Prof.Dr. yadollah Malayeri - Vahid Samadi University Of Tehran [email protected] [email protected] Abstract: The present Paper aims to analyse terrorism discourse in the modern Iraqi novel titled Frankenstein in Baghdad by Ahmed Saadawi by using Norman Fairclough's critical discourse analysis theory. The research is divided into two chapters of five sections. The first chapter provides a brief description on "the concept of terrorism", "the concept of discourse" and "terrorism in Iraqi novels". The second chapter deals with an analysis of the practical words in Saadawi’s novel, exploring the role of terrorism discourse in selecting those words. This chapter also addresses the social dimension of terrorism discourse, suggesting that social phenomena results from discourses, especially the dominant one prevailing in the society, much like the terrorism discourse in Iraq society in the post-2003 era. The research also deals with the behavior of power-holders who, in their struggle to sustain unequal relations of power, impose an impression of ideological common sense through background knowledge which is widely-accepted as true in the public opinion. In Saadawi’s view US troops did the same after 2003 in Iraq. The novel’s analysis reveals the role of the dominant discourse, i.e., terrorism discourse, in the establishment of wrong and even dangerous social behaviors among the public, including the development of wrong beliefs, the exploitation of the situation to the detriment of innocent civilians and the trading of death. -

Guide to the William K

Guide to the William K. Everson Collection George Amberg Memorial Film Study Center Department of Cinema Studies Tisch School of the Arts New York University Descriptive Summary Creator: Everson, William Keith Title: William K. Everson Collection Dates: 1894-1997 Historical/Biographical Note William K. Everson: Selected Bibliography I. Books by Everson Shakespeare in Hollywood. New York: US Information Service, 1957. The Western, From Silents to Cinerama. New York: Orion Press, 1962 (co-authored with George N. Fenin). The American Movie. New York: Atheneum, 1963. The Bad Guys: A Pictorial History of the Movie Villain. New York: Citadel Press, 1964. The Films of Laurel and Hardy. New York: Citadel Press, 1967. The Art of W.C. Fields. Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill, 1967. A Pictorial History of the Western Film. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1969. The Films of Hal Roach. New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1971. The Detective in Film. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1972. The Western, from Silents to the Seventies. Rev. ed. New York: Grossman, 1973. (Co-authored with George N. Fenin). Classics of the Horror Film. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1974. Claudette Colbert. New York: Pyramid Publications, 1976. American Silent Film. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978, Love in the Film. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1979. More Classics of the Horror Film. Secaucus, N.J.: Citadel Press, 1986. The Hollywood Western: 90 Years of Cowboys and Indians, Train Robbers, Sheriffs and Gunslingers, and Assorted Heroes and Desperados. Secaucus, N.J.: Carol Pub. Group, 1992. Hollywood Bedlam: Classic Screwball Comedies. Secaucus, N.J.: Carol Pub. Group, 1994. -

Robert James Farley

Robert James Farley UCLA | Department of Comparative Literature 350 Kaplan Hall | University of California | Los Angeles, CA 90095-0001 +1 562 673 2913 %mo&ile' | rfarley(u)la*e+u | ,,,*ro&ertfarley*org Education Degree Programs Ph.D. in progress, University of California, Los Angeles (2019, Candidacy in Comparative Literature, tentative dissertation title: ‘Writing Kwīr Against Empire: Towards A Grassroots Literary Archive of Gender in Arabic’) B.A., 2011, California State University, Long Beach (comparative world literature, minors in history and Middle Eastern studies) Arabic Training Center for Arabic Study Abroad (CASA), 2015-16, Qasid Institute, Amman, Jordan Arabic Language Program, 2013-2014, University of Jordan and Princess Sumaya University for Technology, Amman, Jordan Arabic Language Summer Session, 2012, Middlebury College, Oakland, California Other Semester Exchange, Spring 2009, University of Leicester College of Arts, Humanities, and Law, Leicester, U.K. Publications Chapter “Mahfouz, al-Mutanabbi, and the Canon: Poetics of Deviance in the Masculine Nationalist Discourse of Al-Sukkariyya,” in Constructions of Masculinity in the Middle East, eds. Mohja Kahf and Nadine Sinno. American University in Cairo Press, forthcoming. Articles “Phantom Limbs: Socio-Psychic Contours of the Maimed Body in ‘I used to Count my Friends on my Fingers’,” Wordgathering: A Journal of Disability Poetry and Literature, vol. 13, no. 1, March 2019. “National Allegory and the Parallax View in Tawfīq al-Ḥakīm's Maṣīr Ṣurṣār,” Portals: A Journal in Comparative Literature, vol. 10, 2013. “Intellectual Space in Naguib Mahfouz’s Thartharah fawq al-Nīl,” CSULB McNair Scholars Research Journal, vol. 15, 2011, pp. 31-50. Translations “Getting to Abu Nuwas Street,” short story by Dheya al-Khalidi.