Echoes of Shakespeare's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(23Rd - 28Th August 2017) Pavilions Teignmouth Episodes from Blackadder the Third - Dual & Duality - Sense and Senility - Ink & Incapability

August 2017 In this Edition Chairman’s Welcome Membership Reminder Blackadder III Box office summer closure Princess & the Pea Name of the Theatre Production News Who’s who CHAIRMAN’S WELCOME Our new committee members have had a very busy time since joining us and we are looking forward to more busy months ahead. We are very pleased that they volunteered and only hope that everyone on the committee is able to continue with all their good work, and we again extend our thanks to past committee members too, who also still contribute constantly to T.P. Following on from months of rehearsals with the youngest Tykes, and slightly less with the more senior Tykes and the ‘adults’ we were so pleased to present Peter Pan at the Pavilions Teignmouth in July. It was by no means an easy task and a great many ‘thank you’ messages need to be passed on. Mike and June Hewett spent many hours to design and build the set and then painting was done by Jane Branch and a ‘friend’ - I’m sorry but I cannot remember the lady’s name – to create some wonderful scenes. June also weilded her paint brush in a less artistic way but with more great results. Unfortunately some last minute adjustments were needed once the set had been transported to Pavilions as there was complications with space, but Mike laid aside his Mr Darling costume and spent many more hours with assistance from Iain Ferguson, completing it. The lighting was designed by Daniel Saint; then he had help from some members as they took down the majority of lights from the Ice Factory and re-erected them inside Pavilions. -

Ann-Kathrin Deininger and Jasmin Leuchtenberg

STRATEGIC IMAGINATIONS Women and the Gender of Sovereignty in European Culture STRATEGIC IMAGINATIONS WOMEN AND THE GENDER OF SOVEREIGNTY IN EUROPEAN CULTURE EDITED BY ANKE GILLEIR AND AUDE DEFURNE Leuven University Press This book was published with the support of KU Leuven Fund for Fair Open Access Published in 2020 by Leuven University Press / Presses Universitaires de Louvain / Universitaire Pers Leuven. Minderbroedersstraat 4, B-3000 Leuven (Belgium). Selection and editorial matter © Anke Gilleir and Aude Defurne, 2020 Individual chapters © The respective authors, 2020 This book is published under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial Non-Derivative 4.0 Licence. Attribution should include the following information: Anke Gilleir and Aude Defurne (eds.), Strategic Imaginations: Women and the Gender of Sovereignty in European Culture. Leuven, Leuven University Press. (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) ISBN 978 94 6270 247 9 (Paperback) ISBN 978 94 6166 350 4 (ePDF) ISBN 978 94 6166 351 1 (ePUB) https://doi.org/10.11116/9789461663504 D/2020/1869/55 NUR: 694 Layout: Coco Bookmedia, Amersfoort Cover design: Daniel Benneworth-Gray Cover illustration: Marcel Dzama The queen [La reina], 2011 Polyester resin, fiberglass, plaster, steel, and motor 104 1/2 x 38 inches 265.4 x 96.5 cm © Marcel Dzama. Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner TABLE OF CONTENTS ON GENDER, SOVEREIGNTY AND IMAGINATION 7 An Introduction Anke Gilleir PART 1: REPRESENTATIONS OF FEMALE SOVEREIGNTY 27 CAMILLA AND CANDACIS 29 Literary Imaginations of Female Sovereignty in German Romances -

Southern Music and the Seamier Side of the Rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 1995 The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South Cecil Kirk Hutson Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Folklore Commons, Music Commons, Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Hutson, Cecil Kirk, "The ad rker side of Dixie: southern music and the seamier side of the rural South " (1995). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 10912. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/10912 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthiough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproductioiL In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

The Teacher & Student Notes This Lesson Plan

Student’s page 1 Warm-up Ask and answer these questions. Then, report back to the class with any answers or information. Losing things! • When was the last time you lost something? What was it? • Have you misplaced anything lately? What was it? Did you ever find it again? • Have you ever accused someone of having taken something of yours? What was it? • Why did you accuse them? What happened in the end? • Has anyone ever accused you of having taken something of theirs? What was it? Why did they accuse you? What happened in the end? • How careful are you about putting away your things? How easy is it to find something if you need it? What are your top tips for not losing things? • Have you ever lost any socks? Have any of your socks ever gone missing mysteriously? • Where do you think all the missing socks go? 2 First viewing You’re going to watch a clip from the British comedy series Blackadder the Third, which aired during the 1980s. The series is set in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, a period known as the Regency. For much of this time, King George III was incapacitated due to poor mental health, and his son George, the Prince of Wales, acted as regent, becoming known as “the Prince Regent". The TV series features Prince George and his fictional butler, Edmund Blackadder. Watch the clip once. How would you describe the relationship between the butler and the prince? Who seems to be in charge? 3 Second viewing Watch the video again. -

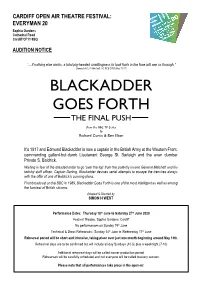

Blackadder Goes Forth the Final Push

CARDIFF OPEN AIR THEATRE FESTIVAL: EVERYMAN 20 Sophia Gardens Cathedral Road Cardiff CF11 9SQ AUDITION NOTICE “... if nothing else works, a total pig-headed unwillingness to look facts in the face will see us through.” General A.C.H. Melchett, VC KCB DSO (May 1917) BLACKADDER GOES FORTH THE FINAL PUSH from the BBC TV Series by Richard Curtis & Ben Elton It's 1917 and Edmund Blackadder is now a captain in the British Army at the Western Front, commanding gallant-but-dumb Lieutenant George St. Barleigh and the even dumber Private S. Baldrick. Waiting in fear of the dreaded order to go 'over the top' from the patently insane General Melchett and his twitchy staff officer, Captain Darling, Blackadder devises serial attempts to escape the trenches always with the offer of one of Baldrick's cunning plans. First broadcast on the BBC in 1989, Blackadder Goes Forth is one of the most intelligent as well as among the funniest of British sitcoms. Adapted & Directed by SIMON H WEST Performance Dates: Thursday 18th June to Saturday 27th June 2020 Festival Theatre, Sophia Gardens, Cardiff No performances on Sunday 19th June Technical & Dress Rehearsals: Sunday 14th June to Wednesday 17th June Rehearsal period will be short and intensive, taking place over just one month beginning around May 14th. Rehearsal days are to be confirmed but will include all day Sundays (10-5) plus a weeknight (7-10) Additional rehearsal days will be called nearer production period. Rehearsals will be carefully scheduled and not everyone will be called to every session. Please note that all performances take place in the open-air. -

Kirkby-In-Ashfield, Nottinghamshire

BBC VOICES RECORDINGS http://sounds.bl.uk Title: Kirkby-in-Ashfield, Nottinghamshire Shelfmark: C1190/26/03 Recording date: 02.02.2005 Speakers: Collishaw, Mark, b. 1972 Crawley, West Sussex; male; fireman (father manager; mother fundraising manager) Duke, Kev, b. 1975 Mexborough, South Yorkshire; male; fireman Johnson, Richard, b. 1967 Mansfield; male; fireman Langton, Ivan, b. 1963 Pinxton, Derbyshire; male; fireman Mason, Danny, b. 1966 Kirkby-in-Ashfield; male; fireman The interviewees are all ex-servicemen currently working as fire-fighters in Nottinghamshire. PLEASE NOTE: this recording is still awaiting full linguistic description (i.e. phonological, grammatical and spontaneous lexical items). A summary of the specific lexis elicited by the interviewer is given below. ELICITED LEXIS ○ see English Dialect Dictionary (1898-1905) * see Survey of English Dialects Basic Material (1962-1971) ▼see Ey Up Mi Duck! Dialect of Derbyshire and the East Midlands (2000) ∆ see New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English (2006) ◊ see Green’s Dictionary of Slang (2010) ♦ see Urban Dictionary (online) ⌂ no previous source (with this sense) identified pleased over t’ moon [ɒvəʔ muːn]; chuffed; happy tired buggered; knackered; shattered; knick knacked♦; chin-strapped∆, chinned♦ (learnt in Army); “as tired as ten …”⌂ (e.g. “I’m as tired as ten WEMs” used in Navy as WEMs1 perceived to be lazy) 1 Abbreviation for ‘Weapons Engineering Mechanic’. http://sounds.bl.uk Page 1 of 3 BBC Voices Recordings unwell don’t feel right; poorly; badly (“badly as a fowl”, “you been badly?” commonly used locally on return to work following illness) hot redders2 (thought to be abbreviation for “red-hot” used of e.g. -

2006/09/29 Vendredi

Ve n d r e d i 29 septembre 2006 Fr.s. 2.- / € 1,30 No 39406 JA 2300 La Chaux-de-Fonds Juste le plus urgent Au grand complet Duel de Neuchâtelois Les moyens financiers à disposition des Avec la nomination de son nouveau se- Ce soir, le Xamaxien Bastien Geiger et le Ponts et chaussées neuchâtelois pour l’en- crétaire général Fabien Greub, le Conseil «Bernois» Joël Magnin s’affrontent en tretien restent sensiblement inférieurs du Jura bernois peut désormais attaquer Coupe à la Charrière. Mais avant cela, ils aux besoins réels. page 2 les dossiers de front. page 14 ont parlé gazon synthétique. page 26 ROUTES CANTONALES CONSEIL DU JURA BERNOIS FOOTBALL LA CHAUX-DE-FONDS Alarme à la Une hausse modérée rue du Signal ASSURANCE MALADIE Soulagement sans euphorie des autorités neuchâteloises: avec 1,3% de hausse, la prime cantonale moyenne reste en dessous de l’augmentation nationale Un crédit est demandé au Conseil général de La Chaux-de-Fonds pour une réfection de l’encorbelle- ment de la rue du Signal. Les travaux sont impératifs et urgents pour des raisons de sécurité. page 5 ÀLAUNE POLITIQUE RÉGIONALE Feu vert du National page 21 FRANCE Lionel Jospin jette l’éponge En 2007, la prime de base de l’assurance maladie grimpera de 1,3% nombreux sont ceux qui voient derrière ces chiffres une manoeuvre page 23 en moyenne dans le canton de Neuchâtel et de 2,2% sur le plan natio- politique visant à couler le projet de caisse unique. PHOTO KEYSTONE nal. Ces hausses particulièrement faibles peuvent réjouir. -

Friday, 1 November Issue 2013/31 the RECTOR

Friday, 1 November We must make the choices that enable us to fulfil the deepest capacities of our real selves. – Thomas Merton Issue 2013/31 THE RECTOR A few weeks ago, I went to a screening of a documentary called Girl co-curricular and pastoral provision through which we encourage a Rising. It described the struggles of nine girls from a variety of bountiful development of gifts for others. Co-operating in the mission of developing countries. Several well-known actors helped with the the Church: we want to witness to Christ’s presence in the world, to narration. The following statistics from the film give pause for find and form Christian community and to participate in Church life. reflection. In the world today, there are 33 million fewer girls than We seek to serve the needs of the world and the Church especially in boys in primary school. 66 million girls are out of school globally. If the light of the apostolic aims of the Jesuits. India enrolled 1% more girls in secondary school, its GDP would rise How do we want our students to by $5.5 billion. A girl with an extra year of education can earn 20% turn out as a result of this special more as an adult. Girls with eight years of education are four times kind of formation? We hope they less likely to be married as children. 14 million girls under 18 will be will be (a) intellectually competent, married this year – that’s 13 girls in the last 30 seconds. In a single (b) open to growth, (c) religious, year, an estimated 150 million girls are victims of sexual violence. -

P32 Layout 1

TV PROGRAMS MONDAY, JANUARY 6, 2014 08:05 Cash In The Attic 19:20 Mako Mermaids 08:50 Bargain Hunt 19:40 Violetta 09:35 Bargain Hunt 20:30 Violetta Don’t miss out! 10:20 Rhodes Across Italy 21:15 Violetta 11:05 Rhodes Across Italy 22:00 Violetta 00:50 Untamed & Uncut 11:50 Rick Stein’s Taste Of Italian 22:50 Violetta American Idol returns 01:45 Gator Boys Opera 23:35 Wizards Of Waverly Place 02:35 Animal Cops Philadelphia 12:40 Bill’s Kitchen: Notting Hill to OSN screens this 03:25 Sharks Of Palau 13:05 MasterChef 04:15 America’s Cutest Pets 13:35 MasterChef 05:05 Too Cute! 14:25 DIY SOS: The Big Build month with season 13 05:55 Animal Cops Philadelphia 15:15 Antiques Roadshow 06:45 Wildest Islands 16:10 Antiques Roadshow 00:00 Chelsea Lately 07:35 Wildlife SOS 17:05 Extreme Makeover: Home 00:30 The Dance Scene 08:00 Meerkat Manor Edition Specials 00:55 The Dance Scene 08:25 My Cat From Hell 18:25 Gok’s Clothes Roadshow 01:25 THS 09:15 America’s Cutest... 19:10 Gok’s Clothes Roadshow 03:15 THS 10:10 Weird Creatures With Nick 20:00 Fat & Fatter 04:10 E! Entertainment Special Baker 20:50 Come Dine With Me: 05:05 Extreme Close-Up 11:05 Call Of The Wildman Supersize 05:30 Extreme Close-Up 11:30 Swamp Brothers 22:25 Antiques Roadshow 06:00 THS 12:00 Bondi Vet 23:15 Bargain Hunt: Famous Finds 07:50 Style Star 12:55 Wildest Islands 08:20 E! News 13:50 Cheetah Kingdom 09:15 Opening Act 14:20 Cheetah Kingdom 10:15 Eric And Jessie: Game On 14:45 Cheetah Kingdom 10:40 Eric And Jessie: Game On 15:15 Cheetah Kingdom 11:10 E!ES 15:40 Cheetah Kingdom -

Echoes of Shakespeare's

Johnson Borrowed robes and garbled transmissions University of Southern Queensland, Australia Laurie Johnson Borrowed robes and garbled transmissions: echoes of Shakespeare’s dwarfish thief Abstract: When Shakespeare’s plays are creatively reinterpreted or rewritten, ‘Shakespeare’ invariably remains locked in as the fixed point of reference: rewritings of Shakespeare; reinterpretations of Shakespeare, and so on. Since 1753, Shakespeare source studies have been mapping the source materials on which his plays were based, which should have enabled us to loosen this fixed point of reference and to begin to picture the much longer history of reinterpretations in which the plays participate. Yet traditional approaches to Shakespeare source studies merely lock in a new point of reference, encompassing both source text and play. This paper aims to show that the new source studies unravels the notion of an ‘original’ by enabling us to unlock broader fields of exchange within which Shakespeare’s texts and our interpretations circulate together. Using the example of Macbeth and the language of borrowing and robbery within it, this essay illustrates the capacity for creative or writerly engagements with a Shakespearean text to tap, perhaps even unconsciously at times, into a history of words and images that goes far beyond the 400 years that we are marking in this year of Shakespeare. Biographical note: Laurie Johnson is Associate Professor (English and Cultural Studies) at the University of Southern Queensland and President elect of the Australian and New Zealand Shakespeare Association. His publications include The Tain of Hamlet (Cambridge Scholars, 2013), The Wolf Man’s Burden (Cornell, 2001), Embodied Cognition and Shakespeare’s Theatre: The Early Modern Body-Mind (co-edited with John Sutton and Evelyn Tribble, Routledge, 2014), and Rapt in Secret Studies: Emerging Shakespeares (co-edited with Darryl Chalk, Cambridge Scholars, 2010). -

The Seventh and Final Chapter of the Harry Potter Story Begins As Harry

“Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2,” is the final adventure in the Harry Potter film series. The much-anticipated motion picture event is the second of two full-length parts. In the epic finale, the battle between the good and evil forces of the wizarding world escalates into an all-out war. The stakes have never been higher and no one is safe. But it is Harry Potter who may be called upon to make the ultimate sacrifice as he draws closer to the climactic showdown with Lord Voldemort. It all ends here. “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 2” stars Daniel Radcliffe, Rupert Grint and Emma Watson, reprising their roles as Harry Potter, Ron Weasley and Hermione Granger. The film’s ensemble cast also includes Helena Bonham Carter, Robbie Coltrane, Warwick Davis, Tom Felton, Ralph Fiennes, Michael Gambon, Ciarán Hinds, John Hurt, Jason Isaacs, Matthew Lewis, Gary Oldman, Alan Rickman, Maggie Smith, David Thewlis, Julie Walters and Bonnie Wright. The film was directed by David Yates, who also helmed the blockbusters “Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix,” “Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince” and “Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows – Part 1.” David Heyman, the producer of all of the Harry Potter films, produced the final film, together with David Barron and J.K. 1 Rowling. Screenwriter Steve Kloves adapted the screenplay, based on the book by J.K. Rowling. Lionel Wigram is the executive producer. Behind the scenes, the creative team included director of photography Eduardo Serra, production designer Stuart Craig, editor Mark Day, visual effects supervisor Tim Burke, special effects supervisor John Richardson, and costume designer Jany Temime. -

Catalogo Dei Film E Degli Episodi Televisivi Contenenti Allusioni E Shakespeare

appendice Catalogo dei film e degli episodi televisivi contenenti allusioni e Shakespeare a cura di Mariangela Tempera ALL’S WELL THAT ENDS WELL ALL'S WELL THAT ENDS WELL Ian Charleson, Angela Down, Michael Hordern, Celia Johnson. regia: Elijah Moshinsky, 1981. Versione della BBC. ing. col. 2h35’ dvd AL A 1 ALL'S WELL THAT ENDS WELL Versione del 'Globe Theatre'. regia: John Dove, 2011. ing. col. 2h18' cf AL A 3 TUTTO E' BENE QUEL CHE FINISCE BENE Ian Charleson, Michael Hordern, Celia Johnson. regia: Elijah Moshinsky, 1981. Versione italiana della produzione BBC. it. col. 2h35’ dvd AL A 2 SAU SARUM JENUM CHEVATA SARUM Versione indiana presentata al Globe Theatre di Londra. regia: Sunil Shanbag, 2012. guj. col. 2h16' cf AL B 1 CRIBB 1.6: WOBBLE TO DEATH Cit. di 'All's well that ...' regia: Gordon Flemyng, 1980. ing. col. 51' cf AL D 9 CRIMINAL MINDS 3.9: PENELOPE Il narratore cita "love all, trust a few .." regia: Félix Enríquez Alcalà, 2007. ing. col. 43' dvd cf AL D 2 da 36 VUES DU PIC SAINT LOUP Un personaggio cita "All's well..." regia: Jacques Rivette, 2009. fra. col. 30" dvd AL D 3 da DARK COMMAND Sh. doveva essere texano perché 'All's well that ...' è un detto regia: Raoul Walsh, 1940. texano. ing. b/n 1' cf AL D 8 FUTARI WA PRETTY CURE 24: MATCH POINT! Cit. del titolo di All's well... regia: Daisuke Nishio 2009 [2004]. ing. col. 24' cf AL D 7 GOLDEN GIRLS 1.16: THE TRUTH WILL OUT Cit.