Vocal Behaviour and Annual Cycle of the Western Bowerbird Chlamydera Guttata

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

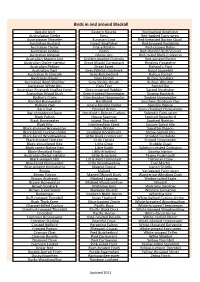

Birds in and Around Blackall

Birds in and around Blackall Apostle bird Eastern Rosella Red backed Kingfisher Australasian Grebe Emu Red-backed Fairy-wren Australasian Shoveler Eurasian Coot Red-breasted Button Quail Australian Bustard Forest Kingfisher Red-browed Pardalote Australian Darter Friary Martin Red-capped Robin Australian Hobby Galah Red-chested Buttonquail Australian Magpie Glossy Ibis Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo Australian Magpie-lark Golden-headed Cisticola Red-winged Parrot Australian Owlet-nightjar Great (Black) Cormorant Restless Flycatcher Australian Pelican Great Egret Richard’s Pipit Australian Pipit Grey (White) Goshawk Royal Spoonbill Australian Pratincole Grey Butcherbird Rufous Fantail Australian Raven Grey Fantail Rufous Songlark Australian Reed Warbler Grey Shrike-thrush Rufous Whistler Australian White Ibis Grey Teal Sacred Ibis Australian Ringneck (mallee form) Grey-crowned Babbler Sacred Kingfisher Australian Wood Duck Grey-fronted Honeyeater Singing Bushlark Baillon’s Crake Grey-headed Honeyeater Singing Honeyeater Banded Honeyeater Hardhead Southern Boobook Owl Barking Owl Hoary-headed Grebe Spinifex Pigeon Barn Owl Hooded Robin Spiny-cheeked Honeyeater Bar-shouldered Dove Horsfield's Bronze-Cuckoo Splendid Fairy-wren Black Falcon House Sparrow Spotted Bowerbird Black Honeyeater Inland Thornbill Spotted Nightjar Black Kite Intermediate Egret Square-tailed kite Black-chinned Honeyeater Jacky Winter Squatter Pigeon Black-faced Cuckoo-shrike Laughing Kookaburra Straw-necked Ibis Black-faced Woodswallow Little Black Cormorant Striated Pardalote -

A LIST of the VERTEBRATES of SOUTH AUSTRALIA

A LIST of the VERTEBRATES of SOUTH AUSTRALIA updates. for Edition 4th Editors See A.C. Robinson K.D. Casperson Biological Survey and Research Heritage and Biodiversity Division Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australia M.N. Hutchinson South Australian Museum Department of Transport, Urban Planning and the Arts, South Australia 2000 i EDITORS A.C. Robinson & K.D. Casperson, Biological Survey and Research, Biological Survey and Research, Heritage and Biodiversity Division, Department for Environment and Heritage. G.P.O. Box 1047, Adelaide, SA, 5001 M.N. Hutchinson, Curator of Reptiles and Amphibians South Australian Museum, Department of Transport, Urban Planning and the Arts. GPO Box 234, Adelaide, SA 5001updates. for CARTOGRAPHY AND DESIGN Biological Survey & Research, Heritage and Biodiversity Division, Department for Environment and Heritage Edition Department for Environment and Heritage 2000 4thISBN 0 7308 5890 1 First Edition (edited by H.J. Aslin) published 1985 Second Edition (edited by C.H.S. Watts) published 1990 Third Edition (edited bySee A.C. Robinson, M.N. Hutchinson, and K.D. Casperson) published 2000 Cover Photograph: Clockwise:- Western Pygmy Possum, Cercartetus concinnus (Photo A. Robinson), Smooth Knob-tailed Gecko, Nephrurus levis (Photo A. Robinson), Painted Frog, Neobatrachus pictus (Photo A. Robinson), Desert Goby, Chlamydogobius eremius (Photo N. Armstrong),Osprey, Pandion haliaetus (Photo A. Robinson) ii _______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS -

Birds on Farms

Border Rivers Birds on Farms INTRODUCTION Grain & Graze Forty-seven mixed farms within nine regions around Australia took part in BR All collecting ecological data for the biodiversityBorder section of the nationalRivers Grain Region and Graze project. Table 1 Bird Survey Statistics Farms Farms Native bird species 105 183 This factsheet outlines the results from bird surveys, conducted in Spring 2006 and Autumn 2006-2007, on five farms within the Border Rivers Region in Introduced bird species 1 6 Queensland and New South Wales. Listed Threatened Species** 7 33 NSW Listed Species 1 11 Four paddock types were surveyed, Crop, Rotation, Pasture and Remnant (see overleaf for link to methods). Although, more bird species were recorded Priority Species 3 15 in remnant vegetation, birds were also frequently observed in other land use ** State and/or Federally types (Table 2). Table 2 List of bird species recorded in each paddock in all of the 5 Border Rivers Region farms. Food Food Common Name Preference Crop Rotation Pasture RemnantCommon Name Preference Crop Rotation Pasture Remnant Grey-crowned Babbler (N) I 1 3 1 2 3 4 Brown Goshawk IC 4 Varied Sittella I 3 White-faced Heron IC 3 White-winged Triller IGF 3 3 4 5 White-necked Heron IC 3 Striped Honeyeater IN 1 3 1 3 2 3 4 Olive-backed Oriole IF 3 Blue-faced Honeyeater IN 1 1 2 3 5 Pacific Black Duck IG 3 5 Brown Honeyeater IN 5 Little Button-quail IG 3 Red-winged Parrot G 1 1 2 5 Noisy Miner IN 4 1 2 3 4 5 3 1 2 3 4 5 Wedge-tailed Eagle C 4 2 3 5 Little Friarbird IN 1 3 Brown Thornbill I -

An Inverse Relationship Between Decoration and Food Colour Preferences in Satin Bowerbirds Does Not Support the Sensory Drive Hypothesis

ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR, 2006, 72, 1125e1133 doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2006.03.015 An inverse relationship between decoration and food colour preferences in satin bowerbirds does not support the sensory drive hypothesis GERALD BORGIA*† & JASON KEAGY† *Department of Biology, University of Maryland, College Park yDepartment of Behavior, Ecology, Evolution and Systematics Program, University of Maryland, College Park (Received 20 September 2005; initial acceptance 25 October 2005; final acceptance 30 March 2006; published online 26 September 2006; MS. number: A10246) Male bowerbirds collect and decorate their bowers with coloured objects that influence female choice. A recent version of the sensory drive hypothesis claims that female food colour preferences have driven the evolution of female preferences for the colour of male display traits. This hypothesis predicts a positive correlation between male display and food colour preferences. A positive correlation between food and decoration preferences could also arise because of sensory biases built into bowerbirds or the environment. Here we test hypotheses that (1) male and female satin bowerbirds show well-defined food colour prefer- ences, (2) these preferences correlate with independently assessed preferences for bower decorations, and, in a cross-species comparison, (3) food items were used as the first bower decorations. We found that male and female satin bowerbirds, Ptilonorhynchus violaceus, preferentially use long wavelength and were colours as food items. Male decoration preferences were biased towards colours of short wavelength and were negatively correlated with food colour preferences. Our reconstruction of ancestral character states is most consistent with the hypothesis that the original bower decorations were inedible objects and were thus unlikely to have been dual-use traits that also functioned as food items. -

SBOC Full Bird List

Box 1722 Mildura Vic 3502 BirdLife Mildura - Full Bird List Please advise if you see birds not on this list Date Notes Locality March 2012 Observers # Denotes Rarer Species Emu Grey Falcon # Malleefowl Black Falcon Stubble Quail Peregrine Falcon Brown Quail Brolga Plumed Whistling-Duck Purple Swamphen Musk Duck Buff-banded Rail Freckled Duck Baillon's Crake Black Swan Australian Spotted Crake Australian Shelduck Spotless Crake Australian Wood Duck Black-tailed Native-hen Pink-eared Duck Dusky Moorhen Australasian Shoveler Eurasian Coot Grey Teal Australian Bustard # Chestnut Teal Bush Stone-curlew Pacific Black Duck Black-winged Stilt Hardhead Red-necked Avocet Blue-billed Duck Banded Stilt Australasian Grebe Red-capped Plover Hoary-headed Grebe Double-banded Plover Great Crested Grebe Inland Dotterel Rock Dove Black-fronted Dotterel Common Bronzewing Red-kneed Dotterel Crested Pigeon Banded Lapwing Diamond Dove Masked Lapwing Peaceful Dove Australian Painted Snipe # Tawny Frogmouth Latham's Snipe # Spotted Nightjar Black-tailed Godwit Australian Owlet-nightjar Bar-tailed Godwit White-throated Needletail Common Sandpiper # Fork-tailed Swift Common Greenshank Australasian Darter Marsh Sandpiper Little Pied Cormorant Wood Sandpiper # Great Cormorant Ruddy Turnstone Little Black Cormorant Red-necked Stint Pied Cormorant Sharp-tailed Sandpiper Australian Pelican Curlew Sandpiper Australasian Bittern Painted Button-quail # Australian Little Bittern Red-chested Button-quail White-necked Heron Little Button-quail Eastern Great Egret Australian -

Evolution of Bower Complexity and Cerebellum Size in Bowerbirds

Original Paper Brain Behav Evol 2005;66:62–72 Received: September 1, 2004 Returned for revision: September 21, 2004 DOI: 10.1159/000085048 Accepted after revision: January 3, 2005 Published online: April 25, 2005 Evolution of Bower Complexity and Cerebellum Size in Bowerbirds a–c d b Lainy B. Day David A. Westcott Deborah H. Olster a b Departments of Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Biology and Psychology, University of California, c Santa Barbara, Calif. , USA; Department of Zoology and Tropical Ecology, School of Tropical Biology, d James Cook University, Townsville , CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems and Rainforest CRC, Atherton , Australia Key Words Introduction Birds Bowerbirds Cerebellum Hippocampus Sexual selection Males of the bowerbird family (Ptilonorhynchidae), except three monogamous species, build elaborate dis- play sites (bowers) used to entice females to mate [Mar- Abstract shall, 1954; Kusmierski et al., 1997]. Bower design ap- To entice females to mate, male bowerbirds build elabo- pears to have been sexually selected through female choice rate displays (bowers). Among species, bowers range in as females of several species are known to select mates complexity from simple arenas decorated with leaves to based at least partially on the quality of the bower or the complex twig or grass structures decorated with myriad number of particular items used to decorate the bower colored objects. To investigate the neural underpinnings [Borgia and Mueller, 1992; Madden, 2003a]. Each species of bower building, we examined the contribution of vari- of bowerbird has a particular bower style and preference ation in volume estimates of whole brain (WB), telen- for decorations of certain types or colors [Marshall, 1954; cephalon minus hippocampus (TH), hippocampus (Hp) Madden, 2003b]. -

Assessing the Sustainability of Native Fauna in NSW State of the Catchments 2010

State of the catchments 2010 Native fauna Technical report series Monitoring, evaluation and reporting program Assessing the sustainability of native fauna in NSW State of the catchments 2010 Paul Mahon Scott King Clare O’Brien Candida Barclay Philip Gleeson Allen McIlwee Sandra Penman Martin Schulz Office of Environment and Heritage Monitoring, evaluation and reporting program Technical report series Native vegetation Native fauna Threatened species Invasive species Riverine ecosystems Groundwater Marine waters Wetlands Estuaries and coastal lakes Soil condition Land management within capability Economic sustainability and social well-being Capacity to manage natural resources © 2011 State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage The State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. The Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) has compiled this technical report in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. OEH shall not be liable for any damage which may occur to any person or organisation taking action or not on the basis of this publication. Readers should seek appropriate advice when applying the information to -

Bird Report, 1982-1999 Graham Carpenter, Andrew Black

NOVEMBER 2003 93 BIRD REPORT, 1982-1999 GRAHAM CARPENTER, ANDREW BLACK, DAVID HARPER and PHILIPPAHORTON INTRODUCTION added, particularly details of specimens donated to and held by the South Australian Museum. For the nineteen years from 1963 to 1981, · Further details of these specimens are available periodic Bird Reports were collated and published from the Museum. in theSouth Australian Ornithologist(Glover et Priority for inclusion goes to reliable and al. 1964; Glover 1965-1975;Cox 1976a; N. Reid verifiable reports of birds rarely recorded for the 1976; J. Reid 1980; Bransbury 1984; note that state or region, namely those of birds recorded references for this section of the report appear on near or beyond their previously recognised range pp. 96-98). With increasing observations it be limits, unusual numbers and unusual seasonal came more difficult to do justice to all records occurrences, and breeding records. Note also that submitted to the South Australian Ornithological additional details, such as ecological data and Association. John Bransbury (1984) undertook field notes, may be available from the quarterly the demanding task to cover the five years 1977- SAOA Newsletters that are referred to by number 1981, a particularly active period when many of edition, or from the author of the record as SAOA members were engaged in compiling indicated by surnameand initial. records for the first Australian Bird Atlas The SAOA Newsletter Bird Notes and Bird (Blakers, Davies and Reilly 1984). Records for the period were collated and vetted The Bird Reports provided readers with a by Brian Glover until March 1984, Graham summary of interesting records for the year, thus Carpenter to March 1995 and David Harper to encouraging further records to confirm, extend or March 1999(SAOA 1982-1994 and 1994-1999). -

Western Bowerbird Chlamydera Guttata Species No.: 681 Band Size: 07 SS

Australian Bird Study Association Inc. – Bird in the Hand (Second Edition), published on www.absa.asn.au - Revised April 2020 Western Bowerbird Chlamydera guttata Species No.: 681 Band size: 07 SS Morphometrics: Two subspecies with measurements as follows: nominate C.g. guttata ssp. C.g. carteri (central WA – except North-west Cape, (North-west Cape, WA) s-w NT & n-w SA) Adult Male Adult Female Adult Male Adult Female THL: 55.7 – 59.3 mm 56.1 – 59.9 No data 57.1 mm (1) Bill: 23.8 – 31.0 mm 23.3 – 30.4 mm 27.8 – 28.7 mm 87 – 95 mm Wing: 141 – 153 mm 140 – 152 mm 134, 135 mm (2) 135 – 141 mm Tail: 82 – 99 mm 92 – 105 mm 83 – 102 mm 87 – 95 mm Tarsus: 37.4 – 41.2 mm 37.3 – 41.0 mm 37.3 – 38.6 mm 35.5 – 39.0 mm Weight: 128 – 148 g 135 – 148 g 127 – 139 g No data Ageing: Adult (2+) Juvenile Bill: black; dark brown; Forehead, coarsely spotted rufous-brown with finer yellow-brown with dense dark brown crown & nape: blackish-brown scalloping & mottling; streaking; Hindneck: feathers pink grading to mauve at tips that pale brown with cream mottling, feathers together form an erectile mauve-pink are cream with broad with broad brown nuchal crest; fringes and no pink; A post-juvenile moult results in a first immature plumage with all or most juvenile remiges and rectrices and greater primary coverts retained and a small pink nuchal crest develops; Probably attain adult plumage in complete first immature post-breeding moult, at about one year of age; Thus adults should only be aged (2+); It is not known at what age females breed, or at what age males build and maintain a complete bower in which to successfully display and attract females. -

Supplemental Table 1.1.Pdf

Flexible mimics Species Scientific name Family Classification Source Inland thornbill Acanthiza apicalis Acanthizidae Flexible del Hoyo et al 2011 Yellow-rumped thornbill Acanthiza chrysorrhoa Acanthizidae Flexible del Hoyo et al 2011 Simpson and Day 1993, Slater 2009, Armstrong 1963, Chisholm 1932, Chestnut-rumped heathwren Calamanthus (Hylacola) pyrrhopygius Acanthizidae Flexible del Hoyo et al 2011 Rusty mouse-warbler Crateroscelis murina Acanthizidae Flexible Xenocanto 2018, del Hoyo et al 2011 Mountain mouse-warbler Crateroscelis robusta Acanthizidae Flexible del Hoyo et al 2011 Brown gerygone Gerygone mouki Acanthizidae Flexible del Hoyo et al 2011 Fernwren Oreoscopus gutturalis Acanthizidae Flexible del Hoyo et al 2011 Rockwarbler Origma solitaria Acanthizidae Flexible del Hoyo et al 2011 Speckled warbler Pyrrholaemus (Chthonicola) sagittatus Acanthizidae Flexible Simpson and Day 1993, Chisholm 1932, del Hoyo et al 2011 Simpson and Day 1993, Chisholm 1932, Xenocanto 2018, del Hoyo et Redthroat Pyrrholaemus brunneus Acanthizidae Flexible al 2011 Yellow-throated scrubwren Sericornis citreogularis Acanthizidae Flexible del Hoyo et al 2011 Large-billed scrubwren Sericornis magnirostra Acanthizidae Flexible del Hoyo et al 2011 Paddyfield warbler Acrocephalus agricola Acrocephalidae Flexible Garamszegi et al 2007 Great reed warbler Acrocephalus arundinaceus Acrocephalidae Flexible Garamszegi et al 2007 African reed warbler Acrocephalus baeticatus Acrocephalidae Flexible del Hoyo et al 2011 Black-browed reed warbler Acrocephalus bistrigiceps -

James Rennie Bequest Report On

JAMES RENNIE BEQUEST REPORT ON EXPEDITION/PROJECT/CONFERENCE Expedition/Project/Conference Title: Investigation into mimicry quality and repertoire size in the spotted bowerbird ................................................................................................................................................. Travel Dates: In the field from 17th July 2003 to 30th september 2003 ............................................................. Location: Taunton National Park, Dingo, Central Queensland, Australia............................................................ Group Member(s): Neil Hart................................................................................................................. Aims: To investigate the link between mimicry quality and repertoire size in this species ....................................... OUTCOME (not less than 300 words):- Due to unfavourable weather conditions in the field I was unable to carry out my intended project title. However, I was able to study the behaviour of several birds at the bower in this unusual year. Bower location and behaviour of the spotted bowerbird (Chlamydera maculata), and the effect of climate on activity at the bower. The study was carried out on Taunton National Park in Central Queensland, Australia. Due to inactivity of the bowerbirds in the initial period of the study and lower than expected levels of mimicry at this stage of the breeding season, I was unable to carry out the planned study, but was still able to gain some insight into the behaviour -

Characteristic Flora and Vegetation

Keith et al. (2013). Scientific foundations for an IUCN Red List of Ecosystems. PLoS ONE in press Supplementary material 10 MOCK OLIVE - WILGA - PEACH BUSH - CARISSA DRY SUB -TROPICAL SEMI - EVERGREEN VINE THICKET IN SOUTH EASTERN AUSTRALIA . Contributed by J.S. Benson, Royal Botanic Gardens and Domain Trust, Sydney Australia, January 2012. CLASSIFICATION International Terrestrial Vegetation Classification (adapted from Faber-Langendoen et al. 2012): Terrestrial Natural Vegetation: Formation Class: Forest – Woodland / Formation Subclass: Tropical Forest / Formation Tropical Seasonally Dry Forest / Division: Sub-tropical Dry Rainforest / Alliance: Semi-evergreen Vine Thicket / Association (Colloquial Name) : Mock Olive - Wilga - Peach Bush - Carissa dry sub-tropical semi-evergreen vine thicket in south eastern Australia. Dominant plant species : Notelaea microcarpa var. microcarpa - Geijera parviflora - Ehretia membranifolia - Elaeodendron australe var. integrifolium / Carissa ovata - Beyeria viscosa - Spartothamnella juncea - Solanum parvifolium / Austrostipa verticillata - Panicum queenslandicum var. queenslandicum - Austrodanthonia bipartita - Dichondra sp. A . Level of Classification : Association. IUCN Habitats Classification (version 3.0): 1. Forest / 1.5 Subtropical – Tropical Dry Biogeographic Realm : Australasian, New South Wales (NSW) Key references : Defined as plant community ID147 in the NSW vegetation classification and assessment database of Benson et al . 2010. Detailed analysis of plant species composition and regeneration ecology is documented in Curran (2006). Assessment of avifauna for part of the distribution is provided in Holmes (1979). Fauna is described for a key site in (NSW NPWS 2004). ECOSYSTEM DESCRIPTION Characteristic Flora and Vegetation Mid-high to low closed or open forest known as semi-evergreen vine thicket dominated by rich diversity of low trees and shrubs to about 6 m high (Figs.