Local Traditions of Bower Decoration by Spotted Bowerbirds in a Single Population

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nest, Egg, Incubation Behaviour and Parental Care in the Huon Bowerbird Amblyornis Germana

Australian Field Ornithology 2019, 36, 18–23 http://dx.doi.org/10.20938/afo36018023 Nest, egg, incubation behaviour and parental care in the Huon Bowerbird Amblyornis germana Richard H. Donaghey1, 2*, Donna J. Belder3, Tony Baylis4 and Sue Gould5 1Environmental Futures Research Institute, Griffith University, Nathan 4111 QLD, Australia 280 Sawards Road, Myalla TAS 7325, Australia 3Fenner School of Environment and Society, The Australian National University, Canberra ACT 2601, Australia 4628 Utopia Road, Brooweena QLD 4621, Australia 5269 Burraneer Road, Coomba Park NSW 2428, Australia *Corresponding author. Email: [email protected] Abstract. The Huon Bowerbird Amblyornis germana, recently elevated to species status, is endemic to montane forests on the Huon Peninsula, Papua New Guinea. The polygynous males in the Yopno Urawa Som Conservation Area build distinctive maypole bowers. We document for the first time the nest, egg, incubation behaviour, and parental care of this species. Three of the five nests found were built in tree-fern crowns. Nest structure and the single-egg clutch were similar to those of MacGregor’s Bowerbird A. macgregoriae. Only the female Huon Bowerbird incubated. Mean length of incubation sessions was 30.9 minutes and the number of sessions daily was 18. Diurnal incubation constancy over a 12-hour day was 74%, compared with a mean of ~70% in six other members of the bowerbird family. The downy nestling resembled that of MacGregor’s Bowerbird. Vocalisations of a female Huon Bowerbird at a nest with a nestling -

Variation in Birdsong of Red Vented Bulbul ( Pycnonotus Cafer) Inhabiting Two Different Locations

Journal of Experimental Sciences 2012, 3(8): 21-25 ISSN: 2218-1768 Available Online: http://jexpsciences.com/ Variation in birdsong of red vented bulbul ( Pycnonotus cafer) Inhabiting two different locations Manjunath and Bhaskar Joshi Department of Zoology, Gulbarga University, Gulbarga, Karnataka, India Abstract This species emits a high variety of acoustic signals in their communication. The signals may be long or short and simple; these signals can be classified into songs and calls. Individuals sang throughout the year. The songs of red-vented bulbul (pycnonotus cafer ) in two regions: Gulbarga and Ainoli were studied during the period from March 2008 to June 2009. The results show that variations exist in this bird species. The songs of birds from two regions shows differences in the tone characteristics, number of syllables, duration, spectral features and frequency range of the main sentence and so on. Keywords: Pycnonotus cafer, Gulbarga, Ainoli. INTRODUCTION from which are unlikely to meet each other. Significant The vocalizations of animals are unique in that they lend macrogeographic differences between populations have been themselves readily to accurate and objective analysis, made possible demonstrated in several species, such as Lincoln’s Sparrows through the recently improved technical aids in sound recording and (Melospiza lincolnii ) (Cicero and Benowitz-Fredericks 2000), Song analysis. Birds use an array of vocal signals in their communication. sparrows ( M. melodia ) (Peters et al., 2000), Willow Flycatchers These signals may be long and complex or short and simple, and (Empidonax trailli ) (Sedgwick 2001), Golden Bowebirds ( Prionodura they may occur in particular contexts (Catchpole and Slater 1995). newtonia ) (Westcoott and Kroon 2002). -

Parental Care and Investment in the Tooth-Billed Bowerbird Scenopoeetes Dentirostris (Ptilonorhynchidae)

VOL. 11 (4) DECEMBER 1985 103 AUSTRALIAN BIRD WATCHER 1985, 11, 103-113 Parental Care and Investment in the Tooth-billed Bowerbird Scenopoeetes dentirostris (Ptilonorhynchidae) By C.B. FRITH and D.W. FRITH, 'Prionodura', Paluma via Townsville, Qld 4816 Summary The known southern distributional limit of the Tooth-billed Bowerbird Scenopoeetes dentirostris is extended from Paluma (19°00'S, 146°l3'E) to Mt Elliot(l9°30'S, 146°57'E) near Townsville, Queensland. Records of the rarely found nest of Scenopoeetes, clutch size, egg weight, egg-laying and nestling periods are summarised. Systematic observations over 45 hours at three nests strongly suggest, but do not conclusively prove, uniparentalism presumably by females. Data for a single-nestling brood at one nest are compared with similar data for the uniparental Golden Bowerbird Prionodura newtoniana and monogamous biparental Spotted Catbird Ailuroedus melanotis, which provide further evidence in support of uniparentalism in Scenopoeetes. Meagre nestling diet information is summarised. Parental care and behavioural records are reviewed and previous erroneous and confusing reports discussed. • Introduction The Tooth-billed Bowerbird* Scenopoeetes dentirostris is one of the least known of the 18 bowerbird species and is certainly less known than the other eight species in Australia. It occurs in upland rainforests between c. 600 and 1400 m above sea level from Mt Amos (15°42'S, 145°18'£) southward to Saddle Mountain on Mt Elliot (l9°30'S, 146°57'£) just south of Townsville, Queensland, where Dr George Heinsohn (pers. comm.) was attracted to an active court by typical male vocalisations on 13 November 1980. This is an extension of the previously known southern limit of this bird's range of 55 km due south or 90 km to the south-east from the previously recorded location of Paluma or Mt Spec (Storr 1973, Griffin 1974). -

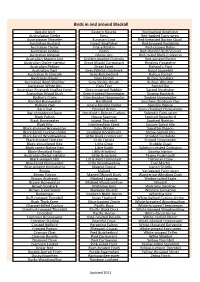

Birds in and Around Blackall

Birds in and around Blackall Apostle bird Eastern Rosella Red backed Kingfisher Australasian Grebe Emu Red-backed Fairy-wren Australasian Shoveler Eurasian Coot Red-breasted Button Quail Australian Bustard Forest Kingfisher Red-browed Pardalote Australian Darter Friary Martin Red-capped Robin Australian Hobby Galah Red-chested Buttonquail Australian Magpie Glossy Ibis Red-tailed Black-Cockatoo Australian Magpie-lark Golden-headed Cisticola Red-winged Parrot Australian Owlet-nightjar Great (Black) Cormorant Restless Flycatcher Australian Pelican Great Egret Richard’s Pipit Australian Pipit Grey (White) Goshawk Royal Spoonbill Australian Pratincole Grey Butcherbird Rufous Fantail Australian Raven Grey Fantail Rufous Songlark Australian Reed Warbler Grey Shrike-thrush Rufous Whistler Australian White Ibis Grey Teal Sacred Ibis Australian Ringneck (mallee form) Grey-crowned Babbler Sacred Kingfisher Australian Wood Duck Grey-fronted Honeyeater Singing Bushlark Baillon’s Crake Grey-headed Honeyeater Singing Honeyeater Banded Honeyeater Hardhead Southern Boobook Owl Barking Owl Hoary-headed Grebe Spinifex Pigeon Barn Owl Hooded Robin Spiny-cheeked Honeyeater Bar-shouldered Dove Horsfield's Bronze-Cuckoo Splendid Fairy-wren Black Falcon House Sparrow Spotted Bowerbird Black Honeyeater Inland Thornbill Spotted Nightjar Black Kite Intermediate Egret Square-tailed kite Black-chinned Honeyeater Jacky Winter Squatter Pigeon Black-faced Cuckoo-shrike Laughing Kookaburra Straw-necked Ibis Black-faced Woodswallow Little Black Cormorant Striated Pardalote -

A LIST of the VERTEBRATES of SOUTH AUSTRALIA

A LIST of the VERTEBRATES of SOUTH AUSTRALIA updates. for Edition 4th Editors See A.C. Robinson K.D. Casperson Biological Survey and Research Heritage and Biodiversity Division Department for Environment and Heritage, South Australia M.N. Hutchinson South Australian Museum Department of Transport, Urban Planning and the Arts, South Australia 2000 i EDITORS A.C. Robinson & K.D. Casperson, Biological Survey and Research, Biological Survey and Research, Heritage and Biodiversity Division, Department for Environment and Heritage. G.P.O. Box 1047, Adelaide, SA, 5001 M.N. Hutchinson, Curator of Reptiles and Amphibians South Australian Museum, Department of Transport, Urban Planning and the Arts. GPO Box 234, Adelaide, SA 5001updates. for CARTOGRAPHY AND DESIGN Biological Survey & Research, Heritage and Biodiversity Division, Department for Environment and Heritage Edition Department for Environment and Heritage 2000 4thISBN 0 7308 5890 1 First Edition (edited by H.J. Aslin) published 1985 Second Edition (edited by C.H.S. Watts) published 1990 Third Edition (edited bySee A.C. Robinson, M.N. Hutchinson, and K.D. Casperson) published 2000 Cover Photograph: Clockwise:- Western Pygmy Possum, Cercartetus concinnus (Photo A. Robinson), Smooth Knob-tailed Gecko, Nephrurus levis (Photo A. Robinson), Painted Frog, Neobatrachus pictus (Photo A. Robinson), Desert Goby, Chlamydogobius eremius (Photo N. Armstrong),Osprey, Pandion haliaetus (Photo A. Robinson) ii _______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS -

Birds on Farms

Border Rivers Birds on Farms INTRODUCTION Grain & Graze Forty-seven mixed farms within nine regions around Australia took part in BR All collecting ecological data for the biodiversityBorder section of the nationalRivers Grain Region and Graze project. Table 1 Bird Survey Statistics Farms Farms Native bird species 105 183 This factsheet outlines the results from bird surveys, conducted in Spring 2006 and Autumn 2006-2007, on five farms within the Border Rivers Region in Introduced bird species 1 6 Queensland and New South Wales. Listed Threatened Species** 7 33 NSW Listed Species 1 11 Four paddock types were surveyed, Crop, Rotation, Pasture and Remnant (see overleaf for link to methods). Although, more bird species were recorded Priority Species 3 15 in remnant vegetation, birds were also frequently observed in other land use ** State and/or Federally types (Table 2). Table 2 List of bird species recorded in each paddock in all of the 5 Border Rivers Region farms. Food Food Common Name Preference Crop Rotation Pasture RemnantCommon Name Preference Crop Rotation Pasture Remnant Grey-crowned Babbler (N) I 1 3 1 2 3 4 Brown Goshawk IC 4 Varied Sittella I 3 White-faced Heron IC 3 White-winged Triller IGF 3 3 4 5 White-necked Heron IC 3 Striped Honeyeater IN 1 3 1 3 2 3 4 Olive-backed Oriole IF 3 Blue-faced Honeyeater IN 1 1 2 3 5 Pacific Black Duck IG 3 5 Brown Honeyeater IN 5 Little Button-quail IG 3 Red-winged Parrot G 1 1 2 5 Noisy Miner IN 4 1 2 3 4 5 3 1 2 3 4 5 Wedge-tailed Eagle C 4 2 3 5 Little Friarbird IN 1 3 Brown Thornbill I -

An Inverse Relationship Between Decoration and Food Colour Preferences in Satin Bowerbirds Does Not Support the Sensory Drive Hypothesis

ANIMAL BEHAVIOUR, 2006, 72, 1125e1133 doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2006.03.015 An inverse relationship between decoration and food colour preferences in satin bowerbirds does not support the sensory drive hypothesis GERALD BORGIA*† & JASON KEAGY† *Department of Biology, University of Maryland, College Park yDepartment of Behavior, Ecology, Evolution and Systematics Program, University of Maryland, College Park (Received 20 September 2005; initial acceptance 25 October 2005; final acceptance 30 March 2006; published online 26 September 2006; MS. number: A10246) Male bowerbirds collect and decorate their bowers with coloured objects that influence female choice. A recent version of the sensory drive hypothesis claims that female food colour preferences have driven the evolution of female preferences for the colour of male display traits. This hypothesis predicts a positive correlation between male display and food colour preferences. A positive correlation between food and decoration preferences could also arise because of sensory biases built into bowerbirds or the environment. Here we test hypotheses that (1) male and female satin bowerbirds show well-defined food colour prefer- ences, (2) these preferences correlate with independently assessed preferences for bower decorations, and, in a cross-species comparison, (3) food items were used as the first bower decorations. We found that male and female satin bowerbirds, Ptilonorhynchus violaceus, preferentially use long wavelength and were colours as food items. Male decoration preferences were biased towards colours of short wavelength and were negatively correlated with food colour preferences. Our reconstruction of ancestral character states is most consistent with the hypothesis that the original bower decorations were inedible objects and were thus unlikely to have been dual-use traits that also functioned as food items. -

SBOC Full Bird List

Box 1722 Mildura Vic 3502 BirdLife Mildura - Full Bird List Please advise if you see birds not on this list Date Notes Locality March 2012 Observers # Denotes Rarer Species Emu Grey Falcon # Malleefowl Black Falcon Stubble Quail Peregrine Falcon Brown Quail Brolga Plumed Whistling-Duck Purple Swamphen Musk Duck Buff-banded Rail Freckled Duck Baillon's Crake Black Swan Australian Spotted Crake Australian Shelduck Spotless Crake Australian Wood Duck Black-tailed Native-hen Pink-eared Duck Dusky Moorhen Australasian Shoveler Eurasian Coot Grey Teal Australian Bustard # Chestnut Teal Bush Stone-curlew Pacific Black Duck Black-winged Stilt Hardhead Red-necked Avocet Blue-billed Duck Banded Stilt Australasian Grebe Red-capped Plover Hoary-headed Grebe Double-banded Plover Great Crested Grebe Inland Dotterel Rock Dove Black-fronted Dotterel Common Bronzewing Red-kneed Dotterel Crested Pigeon Banded Lapwing Diamond Dove Masked Lapwing Peaceful Dove Australian Painted Snipe # Tawny Frogmouth Latham's Snipe # Spotted Nightjar Black-tailed Godwit Australian Owlet-nightjar Bar-tailed Godwit White-throated Needletail Common Sandpiper # Fork-tailed Swift Common Greenshank Australasian Darter Marsh Sandpiper Little Pied Cormorant Wood Sandpiper # Great Cormorant Ruddy Turnstone Little Black Cormorant Red-necked Stint Pied Cormorant Sharp-tailed Sandpiper Australian Pelican Curlew Sandpiper Australasian Bittern Painted Button-quail # Australian Little Bittern Red-chested Button-quail White-necked Heron Little Button-quail Eastern Great Egret Australian -

Evolution of Bower Complexity and Cerebellum Size in Bowerbirds

Original Paper Brain Behav Evol 2005;66:62–72 Received: September 1, 2004 Returned for revision: September 21, 2004 DOI: 10.1159/000085048 Accepted after revision: January 3, 2005 Published online: April 25, 2005 Evolution of Bower Complexity and Cerebellum Size in Bowerbirds a–c d b Lainy B. Day David A. Westcott Deborah H. Olster a b Departments of Ecology, Evolution, and Marine Biology and Psychology, University of California, c Santa Barbara, Calif. , USA; Department of Zoology and Tropical Ecology, School of Tropical Biology, d James Cook University, Townsville , CSIRO Sustainable Ecosystems and Rainforest CRC, Atherton , Australia Key Words Introduction Birds Bowerbirds Cerebellum Hippocampus Sexual selection Males of the bowerbird family (Ptilonorhynchidae), except three monogamous species, build elaborate dis- play sites (bowers) used to entice females to mate [Mar- Abstract shall, 1954; Kusmierski et al., 1997]. Bower design ap- To entice females to mate, male bowerbirds build elabo- pears to have been sexually selected through female choice rate displays (bowers). Among species, bowers range in as females of several species are known to select mates complexity from simple arenas decorated with leaves to based at least partially on the quality of the bower or the complex twig or grass structures decorated with myriad number of particular items used to decorate the bower colored objects. To investigate the neural underpinnings [Borgia and Mueller, 1992; Madden, 2003a]. Each species of bower building, we examined the contribution of vari- of bowerbird has a particular bower style and preference ation in volume estimates of whole brain (WB), telen- for decorations of certain types or colors [Marshall, 1954; cephalon minus hippocampus (TH), hippocampus (Hp) Madden, 2003b]. -

Assessing the Sustainability of Native Fauna in NSW State of the Catchments 2010

State of the catchments 2010 Native fauna Technical report series Monitoring, evaluation and reporting program Assessing the sustainability of native fauna in NSW State of the catchments 2010 Paul Mahon Scott King Clare O’Brien Candida Barclay Philip Gleeson Allen McIlwee Sandra Penman Martin Schulz Office of Environment and Heritage Monitoring, evaluation and reporting program Technical report series Native vegetation Native fauna Threatened species Invasive species Riverine ecosystems Groundwater Marine waters Wetlands Estuaries and coastal lakes Soil condition Land management within capability Economic sustainability and social well-being Capacity to manage natural resources © 2011 State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage The State of NSW and Office of Environment and Heritage are pleased to allow this material to be reproduced in whole or in part for educational and non-commercial use, provided the meaning is unchanged and its source, publisher and authorship are acknowledged. Specific permission is required for the reproduction of photographs. The Office of Environment and Heritage (OEH) has compiled this technical report in good faith, exercising all due care and attention. No representation is made about the accuracy, completeness or suitability of the information in this publication for any particular purpose. OEH shall not be liable for any damage which may occur to any person or organisation taking action or not on the basis of this publication. Readers should seek appropriate advice when applying the information to -

Novitates No

AMERIICAN MUSEUM NOV ITATES PUBLISHED BY THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CITY OF NEW YORK DECEMBER 12, 1952 NUMBER 1602 GEOGRAPHIC VARIATION AND PLUMAGES IN AUSTRALIAN BOWERBIRDS (PTILONORHYNCHIDAE) By ERNST MAYR AND KATE JENNINGS INTRODUCTION In view of the great recent interest in the biology of bower- birds, it is surprising how little is known about the taxonomy of the Australian species. The available accounts in the standard works are very confusing, since no difference is made in most of them between synonyms and valid subspecies. Furthermore, a study of individual variation, of the sequence of plumages, and of measurements is badly needed, as information on these matters is woefully inadequate in the existing literature. In fact, we know much more about the New Guinea species than about the most familiar Australian birds. The following account is based on the material in the American Museum of Natural History which includes the Rothschild and Mathews collections. Where this material proved inadequate, additional specimens were borrowed from the United States National Museum, the Chicago Natural History Museum, the Museum of Comparative Zoology, and the Academy of Natural Sciences of Philadelphia (including parts of the Gould Collec- tion). We greatly appreciate the kindness of the curators of these institutions in making this material available. Ailuroedus crassirostris Paykull GREEN CATBIRD The only two Australian subspecies of this Australo-Papuan species are so different from each other that they were listed as 2 AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES NO. 1602 two species in most of the older literature. However, their essential similarity, the agreement of habits, and the basic dif- ference from buccoides (New Guinea), the only other species of the genus, make it evident that crassirostris Paykull, 1815 (=viridis Vieillot, 1817), and maculosus Ramsay, 1875, must be considered as conspecific. -

Vocal Behaviour and Annual Cycle of the Western Bowerbird Chlamydera Guttata

VOL. 12 (3) SEPTEMBER 1987 83 AUSTRALIAN BIRD WATCHER 1987, 12, 83-90 Vocal Behaviour and Annual Cycle of the Western Bowerbird Chlamydera guttata by JAMES M. BRADLEY, 2 Benbullen Boulevarde, Kingsley, WA. 6026 Summary Bowers of the Western Bowerbird Chlamydera guttata were observed at three sites in coastal Western Australia over three years (1977-1980) in order to quantify song output, mimicry and bower attendance and to determine the timetable of events in the birds' life cycle. Tape recordings of vocalisations at bowers were obtained at regular intervals in all months, and a scoring system was used to measure the rate of song output. Data were also obtained on breeding parameters. Bower-owning males were present at bowers all year, and maintained song output through the year with a major peak in September to December. Mimicry followed a similar pattern, with a peak in July to October. The rate of bower visitation also peaked in these months (August to December). Courtship and copulation were observed in August, eggs in August-September, nestlings in October and fledglings in September and October. Clutch size (n=4) and brood size (n=2) were invariably two. After the mating period, while females were nesting, groups of birds (presumably sub-adult males) visited bowers. Display and visitation rates were low from December to the next breeding cycle. Factors inducing mimicry included intrusion by raptors and humans. It is concluded that males advertise the location of new bowers by increased song output, and that mimicry serves partly as a defence mechanism. Introduction The Western Bowerbird Chlamydera guttata, now regarded as distinct from the Spotted Bowerbird Chlamydera maculata, is a cryptically coloured, sexually monomorphic species inhabiting wooded rocky country in Central and Western Australia (Schodde & Tidemaqn 1986).